Due Friday, May 19 at 2:30 pm Pacific

Solutions are available!

This sixth problem set explores formal language theory, finite automata, the regular languages, and their properties. This will be your first foray into computability theory, and I hope you find it fun and exciting!

As always, please feel free to drop by office hours, ask on Ed, or email the staff list if you have any questions. We'd be happy to help out.

Good luck, and have fun!

Starter Files

Here are the starter files for the problems you'll submit electronically:

Unpack the files somewhere convenient and open up the bundled project.

If you would like to type your solutions in $\LaTeX$, you may want to download this template file where you can place your answers:

Problem One: Constructing DFAs

Download the starter files for Problem Set Six and extract them somewhere convenient on your system. Run the program to access the automaton editor, which you’ll use throughout the problem set. The provided program offers this functionality:

- Automaton Editor: Like the Graph Editor from PS4, use this tool to design automata.

-

Automaton Tester: A tool you can use to test your automata on various input strings. Enter strings in the text box on the left, and the tool will show you which of those strings your automata accepts and which of those strings it rejects. You can follow each string with what you expect the automaton to do, and the tool will tell you whenever the expected output doesn’t match the actual output. For example, you might start with these test strings for the automaton in part (i):

BBIIB yesBBB no

- Automaton Debugger: A tool for single-stepping through the operation of an automaton on a string. You can use this to see how your automata process individual strings.

There’s also an automated test suite you can use to check your work.

For each of the following languages over the indicated alphabets, construct a DFA that accepts precisely the strings that are in the indicated language. Your DFA does not have to have the fewest number of states possible, though for your own edification we’d recommend trying to construct the smallest DFAs possible. Use the Automaton Editor to compose your answers, and submit your finished automata to Gradescope.

-

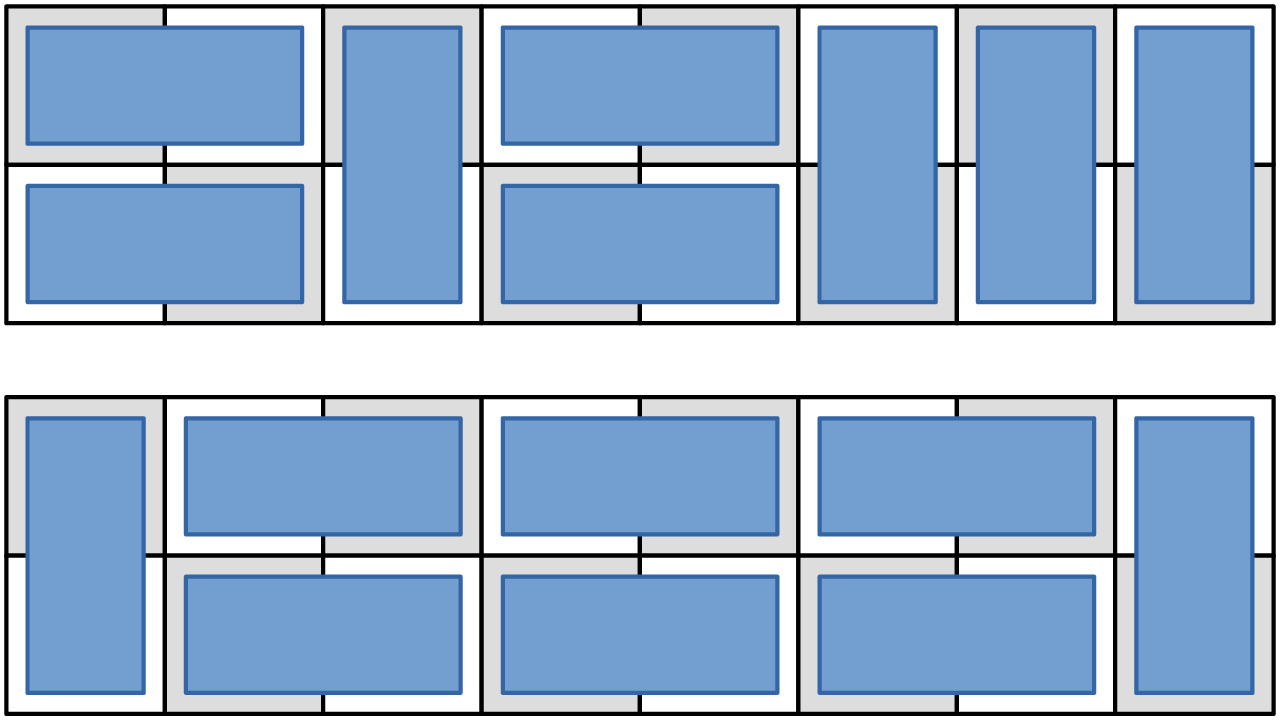

There are many ways to tile a $2 \times 8$ checkerboard with dominoes, two of which are shown here:

Notice that the horizontal dominoes must appear as stacked pairs (do you see why?) We can read each tiling from left to right as a string made from the characters

IandB, whereIdenotes “a vertical domino” andBdenotes “two horizontal dominoes.” The top tiling here would be represented asBIBIIIand the bottom tiling asIBBBI.Let $\Sigma$ be the alphabet $\Set{\mathtt{B}, \mathtt{I}}$. Construct a DFA for the language { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat w$ represents a domino tiling of a $2 \times 8$ checkerboard }.

-

You’re taking a walk with your dog along a straight-line path. Your dog is on a leash of length two, so the distance between you and your dog can be at most two units. You and your dog start at the same position. Consider the alphabet $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{y}, \mathtt{d}}$. A string in $\Sigma^*$ can be thought of as a series of events in which either you or your dog moves forward one unit. For example, the string

yyddmeans you take two steps forward, then your dog takes two steps forward.Let $L$ be the language { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat w$ describes a series of steps where you and your dog are never more than two units apart }. Construct a DFA for $L$.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$. Construct a DFA for the language $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat w$ contains the same number of instances of the substring

aband the substringba}. Note that substrings are allowed to overlap, so we have $\mathtt{aba} \in L$ (one copy of each substring) and $\mathtt{babab} \in L$ (two copies of each substring).

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{c}, \mathtt{m}, \mathtt{o}}$. Construct a DFA for the language $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat w$ contains the word

cocoaas a substring }. For example, $\mathtt{mm\underline{cocoa}mm} \in L$ and $\mathtt{\underline{cocoa}} \in L$, but $\mathtt{c} \notin L$, $\mathtt{cmomcmoma} \notin L$ (thoughcocoais a subsequence ofcmomcmoma, it’s not a substring), and $\varepsilon \notin L$.Some trickier cases to watch for: $\mathtt{ccc\underline{cocoa}} \in L$, and $\mathtt{co\underline{cocoa}} \in L$.

Problem Two: Constructing NFAs

For each of the following languages over the indicated alphabets, use the Automaton Editor to design an NFA that accepts precisely the strings that are in the indicated language. As before, while you don’t have to design the smallest NFAs possible, we recommend that you try to keep your NFAs small both to make testing easier and for your own edification.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}, \mathtt{c}}$. Construct an NFA for { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat w$ ends in

a,bb, orccc}.While it’s possible to do this completely deterministically, it’s a bit easier if you use the “guess-and-check” framework we talked about in class.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}, \mathtt{c}, \mathtt{d}, \mathtt{e}}$. Construct an NFA for the language $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat $ the letters in $w$ are sorted alphabetically }. For example, $\mathtt{abcde} \in L$, $\mathtt{bee} \in L$, $\mathtt{a} \in L$ and $\varepsilon \in L$, but $\mathtt{decade} \notin L$.

You could do this deterministically, but that will require a lot of transitions. You can dramatically reduce that number by using ε-transitions strategically.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}, \mathtt{c}, \mathtt{d}, \mathtt{e}}$. Construct an NFA for the language { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat$ the last character of $w$ appears nowhere else in $w$, and $\abs{w} \ge 1$ }.

This problem is all about embracing nondeterminism. Use the “guess-and-check” framework. What information would you want to guess? How would you check it? Please don’t try to solve this problem by building a DFA for this language; you’ll need at least 50 states if you tried to approach things this way.

Stuck? Try reducing the alphabet to two or three letters and see if you can solve that version.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$. Construct an NFA for the language $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^* \suchthat w$ contains at least two

b's with exactly five characters between them }. For example, $\mathtt{\underline{b}aaaaa\underline{b}} \in L$, $\mathtt{aabaa\underline{b}aaabb\underline{b}} \in L$, and $\mathtt{a\underline{b}bbbba\underline{b}aaaaaaab} \in L$, but $\mathtt{bbbbb} \notin L$, $\mathtt{bbbab} \notin L$, and $\mathtt{aaabab} \notin L$.The smallest DFA for this language is huge, so please don’t solve this one deterministically. Embrace the nondeterminism! What would you like to guess? How would you check that your guess is right?

Problem Three: Notation$

Let $\Sigma$ be an alphabet. Give a short English description of the set $\powerset{\Sigma^*}$.

We think that there is a single “best answer” that makes appropriate use of the terminology from our lectures on formal languages. You should be able to describe the set in at most ten words. Hint: "The set of all subsets of $\Sigma^*$" is not it–that's much too literal. We want a more high-level description of what the expression means.

Problem Four: Much Ado About Nothing, Part II

We’ve covered a bunch of terminology in the past week. This problem is designed to help you make sense of what all these terms mean.

-

Are there any languages $L$ where $\varepsilon \in L$? If so, give an example of one. If not, explain why not.

-

Are there any languages $L$ where $\varepsilon \notin L$? If so, give an example of one. If not, explain why not.

-

Are there any languages $L$ where $\varepsilon \subseteq L$? If so, give an example of one. If not, explain why not.

-

Are there any languages $L$ where $\varepsilon \not\subseteq L$? If so, give an example of one. If not, explain why not.

-

Does $\emptyset = \varepsilon$? Briefly explain your answer.

-

Does $\emptyset = \Set{\varepsilon}$? Briefly explain your answer.

Problem Five: Kleene Stars

Your next task is to prove an important result about powers of languages.

-

Let $L$ be a language over some alphabet $\Sigma$. Prove, by induction, that $L^nL^m = L^{m+n}$ for all natural numbers $m$ and $n\text.$ To do so, prove that the following predicate $P(n)$ is true for all natural numbers $n$:

$P(n)$ is the statement "for all $m \in \naturals$, we have $L^nL^m = L^{m+n}$."

Your proof should leverage the formal definition of language powers, which is reprinted below:

\[L^0 = \Set{\varepsilon} \qquad L^{n+1} = LL^n\]Feel free to use these facts, which you can state without proof:

- Language concatenation is associative: $A(BC) = (AB)C\text.$

- The language $\Set{\varepsilon}$ is the identity language for concatenation: $\Set{\varepsilon}L = L\Set{\varepsilon} = L\text.$

While intuitively we think of $L^k$ as “all strings made of $k$ strings from $L$,” the formal definition of $L^k$ is the inductive one given here. Use that formal definition rather than the higher-level intuition.

Problem Six: Concatenation, Kleene Stars, and Complements

This problem explores some subtle but important properties of language transformations.

-

Prove or disprove: if $L$ is a nonempty, finite language and $k$ is a positive natural number, then $\abs{L}^k = \abs{L^k}$. Here, the notation $\abs{L}^k$ represents “the cardinality of $L$, raised to the $k$th power,” and the notation $\abs{L^k}$ represents “the cardinality of the $k$-fold concatenation of $L$ with itself.”

This is a "prove or disprove" problem, which means that your first task is to figure out whether this statement is true (in which case you'll prove it) or false (in which case you'll disprove it). To disprove a result, you'll write a proof of its negation. Typically, a disproof begins with wording like "We will prove the negation of the claim, specifically, $\blank$" and then proceeds as if it were a regular proof of the negation. Check the Proofwriting Checklist for more details. (But don't take this guidance as a subtle hint that you're supposed to disprove this statement - we're leaving that up for you to decide.)

Since you have to first decide whether this statement or its negation is true, write out both statements and explore each branch to see what you find.

Now, a new definition that we'll make use of later in the quarter. If $L \subseteq \Sigma^\star$ is a language, the complement of $L\text,$ denoted $\overline{L}\text,$ is the language

\[\overline{L} = \Sigma^\star - L\text.\]Intuitively, $\overline{L}$ consists of all the strings over $\Sigma$ that are not in $L\text.$

-

Prove or disprove: there is a language $L$ where $\overline{\left(L^\star\right)} = \left(\overline{L}\right)^\star$.

A good warm-up problem: what is $\emptyset^\star$? Don’t answer this question based off of your intuition; look back at the formal definition of the Kleene star.

To prove the statement $S = T$ where $S$ and $T$ are sets, prove that $S \subseteq T$ and that $T \subseteq S$. To disprove the statement $S = T$, prove that there is some $x$ where either $x \in S$ and $x \notin T$ or $x \in T$ and $x \notin S$.

Optional Fun Problem: Doubling Down

Let $L$ be a regular language over $\Sigma$. Prove that the language $L_{(2)} = \Set{ w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat ww \in L }$ is regular.