Assignment 3: Recursion

Thanks to Julie Zelenski, Jerry Cain, Marty Stepp, Keith Schwarz and Chris Piech

Due: Friday, October 19, 11AM

Must be done individually

The purpose of this assignment is to gain familiarity with recursive problem solving in both graphics and console programs. Note that this assignment must be done individually; you may not work in pairs for this assignment.

This assignment consists of several parts: Fractals, where you implement several recursive algorithms to draw recursive graphics; Grammar Generator, where you recursively generate text based on certain rules, or "grammars"; and Human Pyramid, where you recursively calculate the weight on different members' shoulders in a human pyramid. Each part can be programmed separately, but they should be submitted together. Your output should match exactly as much as possible (e.g. randomization for grammar generator is acceptable, as are slight shifts in fractal output, as long as the images are identical to the expected output by the naked eye). The starter code for this project is available as a ZIP archive (this contains separate QT projects, one for each part of this assignment).

Important Files and Links

Turn in only the following files:

humanpyramid.cpp, the C++ code for the human pyramid function (excluding a main function)fractals.cpp, the C++ code for the fractals functions (excluding a main function)grammargenerator.cpp, the C++ code for the Grammar Generator program (excluding a main function)debugging.txt, a file detailing a bug you encountered in this assignment and how you approached debugging it

Development Strategy and Hints

Here's some clarifications, notifications, expectations, and recommendations for this assignment.

- Your functions must actually use recursion; it defeats the point of the assignment to solve these problems iteratively!

- Do not change any of the function prototypes. We have given you function prototypes for each of the problems in this assignment, and the functions you write must match those prototypes exactly – the same names, the same arguments, the same return types. You are welcome to add your own helper functions if you would like.

- Test your code thoroughly! We'll be running a battery of automated tests on your code, and it would be a shame if you turned in something that almost worked but failed due to a lack of proper testing.

- Recursion is a tricky topic, so don’t be dismayed if you can’t immediately sit down and solve these problems. Please feel free ask for advice and guidance if you need it. Once everything clicks, you’ll have a much deeper understanding of just how cool a technique this is. We’re here to help you get there!

- You can compare your output by saving your images to file using the provided GUI, and using the online image comparison tool with the provided output.

Style

As in other assignments, you should follow our Style Guide for information about expected coding style. You are also expected to follow all of the general style constraints emphasized in the Homework 1 and 2 specs, such as the ones about good problem decomposition, parameters, using proper C++ idioms, and commenting. The following are additional points of emphasis and style constraints specific to this problem:

Recursion: Part of your grade will come from appropriately utilizing recursion to implement your algorithm as described previously. We will also grade on the elegance of your recursive algorithm; don't create special cases in your recursive code if they are not necessary. Avoid "arm's length" recursion, which is where the true base case is not found and unnecessary code/logic is stuck into the recursive case. Redundancy in recursive code is another major grading focus; avoid repeated logic as much as possible. As mentioned previously, it is fine (sometimes necessary) to use "helper" functions to assist you in implementing the recursive algorithms for any part of the assignment.

Variables: While not new to this assignment, we want to stress that you should not make any global or static variables (unless they are constants declared with the const keyword). Do not use globals as a way of getting around proper recursion and parameter-passing on this assignment.

Human Pyramid

A human pyramid is a way of stacking people vertically in a triangle. With the exception of the people in the bottom row, each person splits their weight evenly on the two people below them in the pyramid. For example, in the pyramid to the right, person A splits her weight across people B and C, and person H splits his weight – plus the accumulated weight of the people he’s supporting – onto people L and M. It can be mighty uncomfortable to be in the bottom row, since you'll have a lot of weight on your back! In this question, you'll explore just how much weight that is. Just so we have nice round numbers here, let's assume that everyone in the pyramid weighs exactly 200 pounds.

Person A at the top of the pyramid has no weight on her back. People B and C are each carrying half of person A's weight. That means that each of them are shouldering 100 pounds. Slightly uncomfortable, but not too bad.

Now, let's look at the people in the third row. Let’s begin by focusing on person E. How much weight is she supporting? Well, she’s directly supporting half the weight of person B (100 pounds) and half the weight of person E (100 pounds), so she’s supporting at least 200 pounds. On top of this, she’s feeling some of the weight that people B and C are carrying. Half of the weight that person B is shouldering (50 pounds) gets transmitted down onto person E and half the weight that person C is shouldering (50 pounds) similarly gets sent down to person E, so person E ends up feeling an extra 100 pounds. That means she’s supporting a net total of 300 pounds. That’s going to be noticeable!

Not everyone in that third row is feeling the same amount, though. Look at person D for example. The only weight on person D comes from person B. Person D therefore ends up supporting

- half of person B’s body weight (100 pounds), plus

- half of the weight person B is holding up (50 pounds),

so person D ends up supporting 150 pounds, only half of what E is feeling! Going deeper in the pyramid, how much weight is person H feeling? Well, person H is supporting

- half of person D’s body weight (100 pounds),

- half of person E’s body weight (100 pounds), plus

- half of the weight person D is holding up (75 pounds), plus

- half of the weight person E is holding up (150) pounds.

The net effect is that person H is carrying 425 pounds – ouch! A similar calculation shows that person I is also carrying 425 pounds – can you see why? Compare this to person G. Person G is supporting

- half of person D’s body weight (100 pounds), plus

- half of the weight person D is holding up (75 pounds)

for a net total of 175 pounds. That’s a lot, but it’s not nearly as bad as what person H is feeling! Finally, let’s look at poor person M in the middle of the bottom row. How is she doing? Well, she’s supporting

- half of person H’s body weight (100 pounds),

- half of person I’s body weight (100 pounds),

- half of the weight person H is holding up (212.5 pounds), and

- half of the weight person I is holding up (215.5 pounds),

for a net total of 625 pounds. Yikes! No wonder she looks so unhappy.

There's a nice, general pattern here that lets us compute how much weight is on each person's back:

- Each person weighs exactly 200 pounds.

- Each person supports half the body weight of each of the people immediately above them, plus half of the weight that each of those people are supporting.

Using this general pattern, write a recursive function

double weightOnBackOf(int row, int col);

that takes as input the row and column number of a person in a human pyramid, then returns the total weight on that person's back. The row and column are each zero-indexed, so the person at row 0, column 0 is on top of the pyramid, and person M in the above picture is at row 4, column 2. For example, weightOnBackOf(1, 1) would return 100 pounds (since person C is shouldering 100 pounds on her back), and weightOnBackOf(4, 2) should return 625 (since person M is shouldering a whopping 625 pounds on her back).

Your implementation must be implemented recursively and must not use any loops (for, while, or do ... while) or ADTs (Grid, Vector, Stack). We hope that you'll be pleasantly surprised how little code is required!

Speeding Things Up

When you first code up this function, you'll likely find that it's pretty quick to tell you how much weight is on the back of the person in row 5, column 3, but that it takes a long time to tell you how much weight is on the back of the person in row 30, column 15. Why is this?

Think about what happens if we make a call to weightOnBackOf(30, 15). This will make two new recursive calls: one to weightOnBackOf(29, 14), and one to weightOnBackOf(29, 15). This first recursive call will in turn fire off two of its own calls: one to weightOnBackOf(28, 13), and another to weightOnBackOf(28, 14). The second recursive call fires of two calls: a first recursive call to weightOnBackOf(28, 14), and second one weightOnBackOf(28, 15).

Notice that there are two calls to weightOnBackOf(28, 14) here. This means that there's a redundant call being made to weightOnBackOf(28, 14), so all the work done to compute that intermediate answer is done twice. That call will in turn fire off its own redundant recursive calls, which in turn fire off their own redundant calls, etc. This might not seem like much, but the number of recursive calls can be huge. For example, calling weightOnBackOf(30, 15) makes a whopping 601,080,389 recursive calls!

As a final step in this part of the assignment, once you've gotten everything working, modify your function so that it uses memoization to avoid recomputing values unnecessarily. However, the weightOnBackOf function must still take the same arguments as before, since our starter code expects to be able to call it with just two arguments.

Once you've done that, try comparing how long it takes to evaluate weightOnBackOf(40, 20) both with and without memoization. Notice a difference? For fun, try computing weightOnBackOf(200, 100). This will take a staggeringly long time to complete without memoization – so long, in fact, that the sun will probably burn out before you get an answer – but with memoization you should get back an answer extremely quickly!

Fractals

For this portion of the assignment, we have provided a starter project GUI that lets the user draw various fractals. Your job is to fill in the functions that draw these fractals. The user can specify the coordinates/size/other properties either by filling in the information at the top, or by clicking and dragging to select a bounding box where they wish to draw.

1. Sierpinski Triangle

Sample Output

You can compare your graphical output against the image files below using the online image compare tool linked at the top of the page.

Please note that due to minor differences in pixel arithmetic, rounding, etc., it is very likely that your output will not perfectly match ours. It is okay if your image has non-zero numbers of pixel differences from our expected output, so long as the images look essentially the same to the naked eye when you switch between them.

If you search the web for fractal designs, you will find many intricate wonders beyond the fractals we explored in lecture. One of these is the Sierpinski Triangle, named after its inventor, the Polish mathematician Wacław Sierpiński. The order-0 Sierpinski Triangle is just a regular equilateral triangle. An order-n Sierpinski triangle consists of three order-(n-1) Sierpinski triangles, each half as large as the original, arranged in the corners of a larger triangle. For example, the order-1 Sierpinski triangle is shown below. It consists of three order-0 Sierpinski triangles (each of which is an equilateral triangle) arranged in the corners of a larger triangle. Note that the downward-pointing triangle in the middle of the figure is not drawn explicitly, but is instead formed by the sides of the other three triangles. That area is not recursively subdivided and remains unchanged at every level of the fractal, so the order-2 Sierpinski Triangle has the same open area in the middle, as does order-5.

Order-1

Order-2

Order-5

Your task is to implement the function

void drawSierpinskiTriangle(GWindow& window, double x, double y, double sideLength, int order)

that takes as input the (x, y) coordinates of the bottom-left corner of the triangle, the length of one side of the triangle, and the order of the fractal, then draws a Sierpinski triangle of that order in the window. If the x, y, order, or size passed is negative, your function should throw a string exception. Otherwise you may assume that the window passed is large enough to draw the figure at the given position and size.

Your solution should not use any loops; you must use recursion. Do not use any data structures in your solution such as a Vector, Map, arrays, etc. The provided code already contains a main function that pops up a graphical user interface to allow the user to choose various x/y positions, sizes, and orders. When the user clicks the appropriate button, the GUI will call your function and pass it the relevant parameters as entered by the user. The rest is up to you.

Although you might expect this assignment is going to require a lot of math with sines and cosines, if you structure your program correctly you'll need to do very few trigonometric calculations. We highly recommend structuring your recursive design such that you reference triangles by their 3 corner points instead. This makes it significantly easier to draw triangles, and calculate where further triangles should be located. The GPoint class in the Stanford Libraries will likely come in handy. But do keep in mind that the height h of an equilateral triangle is not the same as its side length s. The diagram below shows the relationship between the triangle and its height. Feel free to use online resources to refresh your memory of equilateral triangles as well.

Also, don’t forget that in our coordinate system, x values increase from left to right (as in the Cartesian plane), but y values increase from top to bottom (the opposite of the regular Cartesian plane).

Finally, avoid re-drawing the same line multiple times. If your code is structured poorly, you end up drawing a line again (or part of a line again) that was already drawn, which is unnecessary and inefficient. If you aren't sure whether your solution is redrawing lines, try making a counter variable that is incremented each time you draw a line and checking its value.

2. Recursive Tree

Sample Output

You can compare your graphical output against the image files below using the online image compare tool linked at the top of the page.

Please note that due to minor differences in pixel arithmetic, rounding, etc., it is very likely that your output will not perfectly match ours. It is okay if your image has non-zero numbers of pixel differences from our expected output, so long as the images look essentially the same to the naked eye when you switch between them.

For this problem, write a recursive function that draws a tree fractal image as specified here. Note that your solution is allowed to use loops if they are useful to help remove redundancy, but that your overall approach to drawing nested levels of the figure must still be recursive. Do not use any data structures in your solution such as a Vector, Map, arrays, etc.

Our tree fractal contains a trunk that is drawn from the bottom center of the applicable area (x, y) through (x + size, y + size). The trunk extends straight up through a distance that is exactly half as many pixels as size.

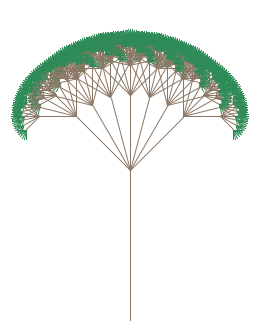

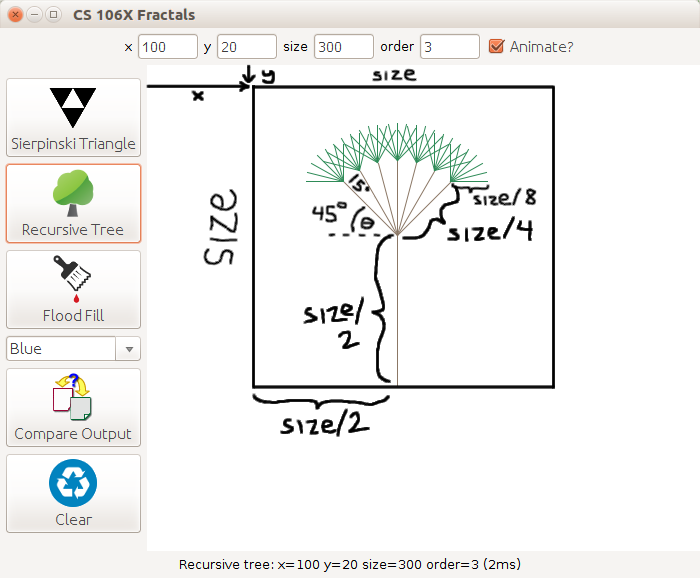

The drawing below is a tree of order 5. Sitting on top of its trunk are seven trees of order 4, each with a base trunk length half as long as the prior order tree’s trunk. Each of the order-4 trees is topped off with seven order-3 trees, which are themselves comprised of seven order-2 trees, and so on.

The parameters passed to your function are, in order: the window in which to draw the figure; the x/y position of the top left corner of the imaginary bounding box surrounding the area in which to draw the figure (more details on this just below); the side width/height of the figure (i.e., the overall size of the square boundary box; see below); and the number of levels, i.e., the order, of the figure.

void drawTree(GWindow& gw, double x, double y, double size, int order)

Some of these parameters are somewhat unintuitive. For example, the x/y coordinates passed are not the x/y coordinates of the tree trunk itself, but rather the coordinates of the bounding box area in which to draw the tree. The following diagram attempts to clarify the parameters visually:

drawTree(gw, 100, 20, 300, 3);Lengths: As this drawing also shows, the trunks of each of the seven subtrees are exactly half as long of their parent branch's length in pixels.

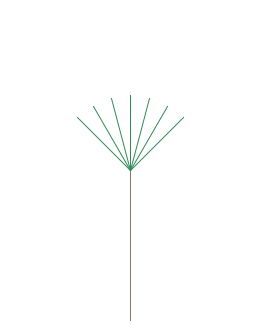

Angles: The seven subtrees extend from the tip of the previous tree trunk at relative angles of ±45, ±30, ±15, and 0 degrees relative to their parent branch's angle. For example, if you look at the Order-1 figure (below), you can think of it as a vertical line drawn in an upward direction and facing upward, which is a polar angle of 90 degrees. In the Order-2 figure, the seven sub-branches extend at angles of 45, 60, 75, 90, 105, 120, and 135 degrees; etc.

Colors: Inner branches (i.e., branches drawn at order 2 and higher) should be drawn in the color #8b7765 (r=139, g=119, b=101), and the leafy fringe branches of the tree (i.e., branches drawn at level 1) should be drawn in the color #2e8b57 (r=46, g=139, b=87).

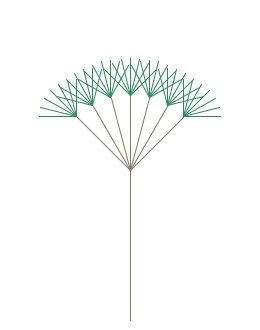

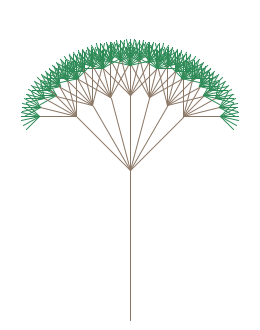

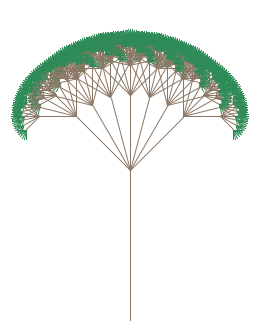

The images below show the progression of the first five orders of the fractal tree figure:

You should use the GWindow object's drawPolarLine() function to draw lines at various angles, and its setColor() function to change drawing colors.

| Member | Description |

|---|---|

gw.drawPolarLine(x0, y0, r, theta); gw.drawPolarLine(p0, r, theta);

|

draws a line the given starting point, of the given length r, at the given angle in degrees theta relative to the origin |

gw.setColor(color); |

sets color used for future shapes to be drawn, either as a hex string such as "#aa00ff" or an RGB integer such as 0xaa00ff |

If the order passed is 0, your function should not draw anything. Similarly, if the x or y coordinates, the order, or the size passed is negative, your function should throw an exception. Otherwise, you may assume that the window passed is large enough to draw the figure at the given position and size.

3. Mandelbrot Set

Sample Output

You can compare your graphical output against the image files below using the online image compare tool linked at the top of the page.

Please note that due to minor differences in pixel arithmetic, rounding, etc., it is very likely that your output will not perfectly match ours. It is okay if your image has non-zero numbers of pixel differences from our expected output, so long as the images look essentially the same to the naked eye when you switch between them.

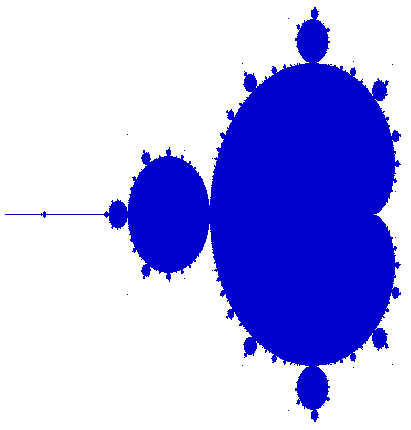

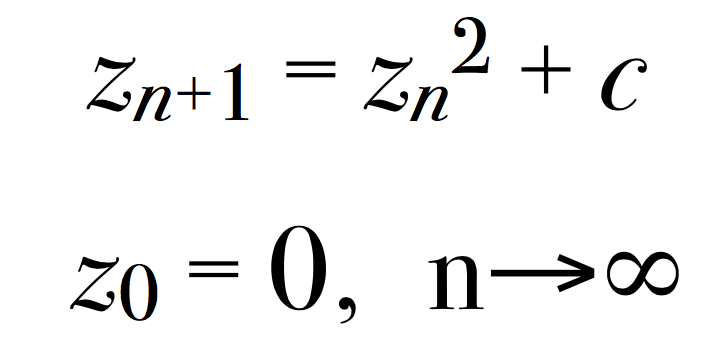

Another fascinating fractal is the "Mandelbrot Set", in tribute to Benoit Mandelbrot, a mathematician who investigated this phenomenon. The Mandelbrot Set is recursively defined as the set of complex numbers, c, for which the function fc(z) = z2 + c does not diverge when iterated from z=0. In other words, a complex number, c, is in the Mandelbrot Set if it does not grow without bounds when the recursive definition is applied. The complex number is plotted as the real component along the x-axis and the imaginary component along the y-axis.

For example, the complex number 0.2 + 0.5i is in the Mandelbrot Set, and therefore, the point (0.2, 0.5) would be plotted on an x-y plane. For this problem, you will map coordinates on an image (via a Grid) to the appropriate complex number plane (note that for this problem, we have abstracted away many details to make the coding easier).

Formally, the Mandelbrot set is the set of values of c in the complex plane that is bounded by the following recursive definition:

In order to test if a number, c, is in the Mandelbrot Set, we recursively update z until either of the following conditions are met:

- The absolute value of z becomes greater than 4 (it is diverging), at which point we determine that c is not in the Mandelbrot Set; or,

- We exhaust a number of iterations, defined by a parameter (usually 200 is sufficient for the basic Mandelbrot Set, but this is a parameter you will be able to adjust), at which point we declare that c is in the Mandelbrot Set.

Because the Mandelbrot Set utilizes complex numbers, we have provided you with a Complex class that contains the following member functions (#include "complex.h" to use it):

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

Complex(double a, double b) |

Constructor that creates a complex number in the form a + bi |

cpx.abs()

|

returns the absolute value of the number (a double) |

cpx.real()

|

returns the real part of the complex number |

cpx.imag()

|

returns the coefficient of the imaginary part of the complex number |

cpx1 + cpx2 |

returns a complex number that is the addition of two complex numbers |

cpx1 * cpx2 |

returns a complex number that is the product of two complex numbers |

ostr << c |

prints a complex number to an output stream |

Implementation Details

Your drawMandelbrotSet function will be passed in a number of parameters that you will use to determine which pixels in the window will be drawn in the Mandelbrot Set. The details of the parameters are described below. Your solution may use loops to traverse the grid, but you must use recursion to determine if a particular point exists in the Mandelbrot Set.

void drawMandelbrotSet(GWindow& window, double leftX, double topY, double size,

const Complex& min, const Complex& max,

int iterations, int color);

The window parameter is the same as in the other parts. In the starter code, we have already created an image that will display the fractal, and created a grid based on that image. The grid is composed of individual pixel values (ints) that you can change based on whether or not a pixel is "in the Mandelbrot Set" or not. How to color the pixels is described below.

The leftX and topY parameters are the (x, y) coordinates of the top-left corner of the overall area in which you should draw your Mandelbrot Set. The size parameter describes the width and height in pixel of the area in which you should draw your Mandelbrot Set. (These can be set by clicking and dragging on the GUI or by entering them in the text boxes.)

The min and max parameters describe the range of complex numbers you should examine. Your code will need to compute a mapping between the x/y pixel range on the screen and the range of complex numbers provided. See the diagram below for more details about performing this mapping. (These are set when you click the Mandelbrot button; the GUI will prompt you for their values.)

The iterations parameter is the maximum number of iterations your algorithm should try on each pixel to decide whether that pixel's corresponding complex number diverges. If the number diverges, you should leave its corresponding pixel untouched. If the number does not diverge after that many iterations, it is in the Mandelbrot Set. (The max number of iterations is set by modifying the "Order" parameter in the GUI. The default of 1 iteration is far too few; you'll need to set a higher number, such as 50 or 200, to see a sharp image.)

The color parameter is parameter is an integer representing an RGB color that you should use to color any pixels that do not diverge in your Mandelbrot Set. Just set the pixel's value in the grid to that color. The grid's pixels are colored white by default.

The following diagram summarizes the mapping you must perform from onscreen x/y coordinates to the complex number space. The figure below is drawn with a top-left pixel value of (x=100, y=20) and a size of 400. The complex numbers min and max are specified to be (-2-i) and (1+i) respectively. Recall that in this exercise the complex numbers are mapped to the x/y coordinate space with their real components on the x-axis and the imaginary i components on the y-axis. This means that for this specific example, your code would need to map the space [-2 .. 1] onto the x-coordinates [100 .. 500], and map the space [-1i .. 1i] onto the y-coordinates [20 .. 420].

So, for example, the pixel (x=100, y=20) represents complex number (-2 -i). Its right-side neighbor, (x=101, y=20), represents roughly (-1.9925 -i), and the next pixel to the right of that, (x=102, y=20), represents roughly (-1.985 -i). Its downward neighbor, (x=100, y=21), represents roughly (-2 -0.995i), and the next pixel below that, (x=100, y=22), represents roughly (-2 -0.99i). The origin of the complex number space, (0+0i), would be at a pixel position of roughly (x=367, y=220). We continue in this fashion until the bottom-right corner of the x/y region, (500, 420), which represents complex number (1+i).

Mapping coordinates: (100, 20)x400 => (-2-i to 1+i)

Note that your drawMandelbrotSet function itself is not directly recursive. You can use loops to iterate over the the range of pixels of interest in the window. But the code that examines each pixel to determine whether or not it diverges must be recursive for full credit and should not use loops. You should probably put such code into a helper function that is called by drawMandelbrotSet.

Debugging: It can be hard to debug this problem because if your calculations are not quite right, you may see no graphical output at all. If you are not seeing any helpful output, try inserting a cout statement for each pixel to verify whether you have properly figured out its corresponding complex number. Also try printing out the number of iterations until each complex number diverges, to help you see whether you are computing that value properly.

4. Plasma Fractals

A Plasma fractal, also known as random midpoint displacement, is a recursive algorithm used to generate superbly cool-looking psychadelic gradients. Take a look:

The algorithm works at a high level by recursively sub-dividing the rectangular area you wish to fill into 4 equal-sized sub-rectangles until you get down to about 1 pixel-sized rectangles, at which point you color each pixel following certain coloring rules. The coloring rules are such that colors change randomly across the fractal, but gradually, to create the appearance of a smooth gradient. The algorithm behind this is used in real-world scenarios to generate terrain maps, which could be used in areas like video game development or movie production (e.g. imagine that lighter colors are higher, and lower colors are lower terrain).

Here's how the algorithm works. Initially, take the rectangle you wish to fill and assign 4 random colors to it, one to each corner. You can visualize this like the following:

If the rectangle has a width or height of at most 1, then it's small enough we can just fill it in. You calculate its color by averaging the colors of its 4 corners. If the rectangle is too big, we need to subdivide it first. So we divide this rectangle into 4 smaller rectangles:

Now we need to process each of these subrectangles. But before we do that, we need to know what each of their corner colors are. We can do this by, on each edge where we need a new color, averaging the colors of the two endpoints of that edge, like so:

The middle point is the lone exception. This point is the average of all 4 colors in the corners, and randomly displaced by a certain amount. This means we add a small random number to it that will slightly change the color. This provides the subtle color gradient you see in the fractal.

Now we continue by processing each of the 4 sub-rectangles we just divided, with their corresponding corner colors. Once we divide all rectangles down to a small enough size, we fill them in and we get a pretty cool-looking fractal.

The user will select an area in the provided GUI that they wish to fill, and the information will be passed to your function.

To help with the implementation, we have provided a variable type calledPlasmaColor that makes handling these colors easier. Here is its functionality.

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

PlasmaColor() |

Constructor that creates a new PlasmaColor with a random color. |

color.toRGBColor()

|

returns the color this variable represents as an int that can be put into a pixel grid. |

color1 + color2 |

returns a color that is the sum of 2 colors. |

color1 / decimal |

returns a color that is the color divided by the provided decimal. |

ostream << color1 |

Outputs the color as a decimal between 0 and 1 to an output stream. |

For example, you can create a new random PlasmaColor as follows:

PlasmaColor myColor;

If you'd then like to get half of that color and get the corresponding int for that color, you could do the following:

myColor /= 2.0; int colorInt = myColor.toRGBColor();

See the included plasmacolor.h file for a full overview of functionality.

To calculate the middle color of a rectangle at a given step, use the provided displace function in the starter code:

displace(double newWidth, double newHeight, double totalWidth, double totalHeight)The parameters are:

newWidth: the width of the subdivided rectangles you are creating at that momentnewHeight: the height of the subdivided rectangles you are creating at that momenttotalWidth: the width of the entire plasma fractal (not just the part you are filling in at the moment)totalHeight: the height of the entire plasma fractal (not just the part you are filling in at the moment)

As an example, let's say I am filling in a plasma fractal of total size 80 x 40 and am processing the following rectangle, where the width is 20 and the height is 10.

At this step, I subdivide into 4 rectangles of size 10 x 5. To calculate the middle color, I take the average of my 4 corners, and then add the displacement value calculated by the above function to that to get the final middle color. For that specific call, the parameters would be displace(10, 5, 80, 40).

You may ask why this displacement function takes these parameters. The displacement function gives you a random value that varies the color slightly. For larger rectangles (e.g. ones that are closer to the size of the total fractal), it varies the color more than for smaller rectangles (e.g. ones that are closer to 1), where it displaces very little. This causes the effect of significant color changes over the entire fractal, but only small changes in local areas of the fractal.

You may not use any loops or data structures for this problem other than the already-provided pixel grid. You must use recursion to fill in each pixel in the fractal.

Because this fractal is generated with randomness, it's not possible to provide expected output. However, your fractal should have a smooth color gradient across the image, and look mostly random (and not like a pattern). Here are some more examples below. One tip for debugging is to print out colors to ensure your calculations seem correct. You can output a color to an output stream, where it will display as a decimal between 0 and 1. This is how they are represented under the hood, so you can verify all math by ensuring that the resulting numbers come out correctly (e.g. averaging colors is just averaging their decimal values).

Grammar Generator

Overview

For this part of the assignment you will write a function to generate random sentences from what linguists, programmers, and logicians refer to as a “grammar.”

Let’s begin with some definitions. A formal language is a set of words and/or symbols along with a set of rules, collectively called the syntax of the language, that define how those symbols may be used together—programming languages like Java and C++ are formal languages, as are certain mathematical or logical notations. A grammar, in this context, is a way of describing the syntax and symbols of a formal language. All programming languages then have grammars; here is a link to a formal grammar for the Java language.

Your task for this problem will be to write a function that accepts a reference to an input file representing a language’s grammar (in a format that we will explain below), along with a symbol to randomly generate, and the number of times to generate it. Your function should generate the given number of random expansions of the given symbol and return them as a Vector of strings.

Vector<string> generateGrammar(istream& input, string symbol,

int times)

Sample Output

Your program should exactly reproduce the format and general behavior demonstrated in these logs, although it may not exactly recreate these particular scenarios because of the randomness inherent in your code. But your function should return valid random results as per the grammar that was given to it. You can use the output comparison tool on the course website with these files.

We have also written a Grammar Verifier web tool where you can paste in the randomly generated sentences and phrases from your program, and our page will do its best to validate that they are legal phrases that could have come from the original grammar file. This isn't a perfect test, but it is useful for finding some common types of mistakes.

Reading BNF Grammars

Many language grammars are described in a format called Backus-Naur Form (BNF), which is what we'll use in this assignment. In BNF, some symbols in a grammar are called terminals because they represent fundamental words of the language (i.e., symbols that cannot be transformed or reduced beyond their current state). A terminal in English might be "dog" or "run" or "Chris". Other symbols of the grammar are called non-terminals and represent higher-level parts of the language syntax, such as a noun phrase or a sentence in English. Every non-terminal consists of one or more terminals; for example, the verb phrase "throw a ball" consists of three terminal words.

The BNF description of a language consists of a set of derivation rules, where each rule names a symbol and the legal transformations that can be performed between that symbol and other constructs in the language. You might think of these rules as providing translations between terminals and other elements, either terminals or non-terminals. For example, a BNF grammar for the English language might state that a sentence consists of a noun phrase and a verb phrase, and that a noun phrase can consist of an adjective followed by a noun or just a noun. Note that rules can be described recursively (i.e., in terms of themselves). For example, a noun phrase might consist of an adjective followed by another noun phrase, such as the phrase "big green tree" which consists of the adjective "big" followed by the noun phrase "green tree".

A BNF grammar is specified as an input file containing one or more rules, each on its own line, of the form:

non-terminal::=rule|rule|rule|...|rule

A separator of ::= (colon colon equals) divides the non-terminal from its transformation/expansion rules. There will be exactly one such ::= separator per line. A | (pipe) separates each rule; if there is only one rule for a given non-terminal, there will be no pipe characters. Each rule will consist of one or more whitespace-separated tokens. To illustrate how to read a BNF grammar, let’s consider a very simple example. Suppose that we had the BNF input file below, which describes a language comprising a tiny subset of English. The non- terminal symbols <s>, <pn>, and <iv> are short for grammatical elements: sentences, proper nouns, and intransitive verbs (i.e., verbs that do not take an object). Note that in the following two examples, non-terminal elements are contained in angle brackets, while terminal elements (here, valid English words, such as “Lupe”, “Camillo”, “laughed”, etc.) are not.

<s>::=<pn> <iv> <pn>::=Lupe|Camillo <iv>::=laughed|wept

To transform a symbol into a valid output string (that is, into a sentence described by this grammar’s rules), we recursively expand the non-terminal symbols contained in its transformation rules until we have an output made up entirely of terminals—at that point our transformation is complete, and we’re done. So in our trivial example of a grammar, if we are given the symbol <s>, which represents the non-terminal for “sentence”, we examine the rules that describe how to expand the sentence non- terminal, and discover that it is comprised of a proper noun followed by an intransitive verb (<s>::=<pn> <iv>). We can begin by transforming the <pn> symbol, which we do by choosing at random from among the available transformations provided on the right-hand side of the <pn> rule (here, “Lupe” and “Camillo”). After this transformation, our sentence-in-progress might look like this:

Camillo <iv>

At each step of our transformation, we perform a single transformation on one of the remaining non- terminal symbols. In this simple example, there is only one non-terminal left, <iv>. We accordingly transform that symbol by choosing randomly among the transformations provided for it, which could produce the following output:

Camillo laughed

Since there are no more non-terminal symbols remaining, our transformation is complete. Note that other valid sentences in this language (i.e., other valid transformations of the symbol <s>) include the sentences “Camillo wept”, “Lupe laughed”, and “Lupe wept”. Because we can choose at random from the transformations provided for each non-terminal symbol, all of these variations are possible and valid for this very simple language.

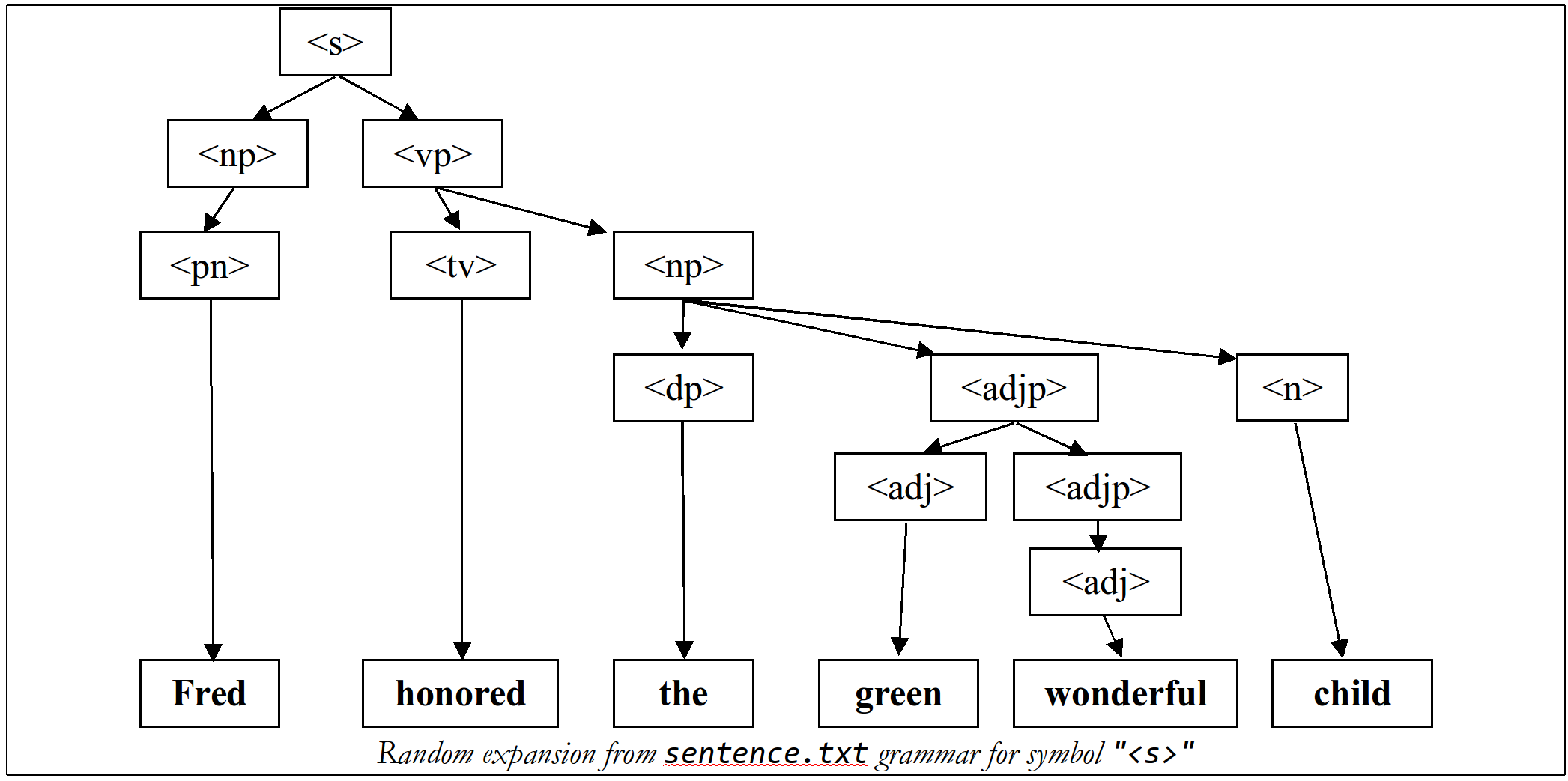

Now let’s look at an example of a more complex BNF input file, sentence.txt, which describes a slightly larger subset of the English language. Here, the non-terminal symbols <np>, <dp>, and <tv> are short for the linguistic elements noun phrase, determinate article, and transitive verb.

<s>::=<np> <vp> <np>::=<dp> <adjp> <n>|<pn> <dp>::=the|a <adjp>::=<adj>|<adj> <adjp> <adj>::=big|fat|green|wonderful|faulty|subliminal|pretentious <n>::=dog|cat|man|university|father|mother|child|television <pn>::=John|Jane|Sally|Spot|Fred|Elmo <vp>::=<tv> <np>|<iv> <tv>::=hit|honored|kissed|helped <iv>::=died|collapsed|laughed|wept

Following the rules provided by this input file for expanding non-terminals, this grammar's language can represent sentences such as "The fat university laughed" and "Elmo kissed a green pretentious television". This grammar cannot describe the sentence "Stuart kissed the teacher", because the words "Stuart" and "teacher" are not part of the grammar. It also cannot describe "fat John collapsed Spot" because there are no rules that permit an adjective before the proper noun "John", nor an object after intransitive verb "collapsed".

Though the non-terminals in the previous two example languages are surrounded by < >, this is not required. By definition any token that ever appears on the left side of the ::= of any line is considered a non-terminal, and any token that appears only on the right-hand side of ::= in any line(s) is considered a terminal (so for the above example, as we have noted, <np> is a non- terminal, but “John” is a terminal). Do not assume that non-terminals will be surrounded by < > in your code. Each line's non-terminal will be a non-empty string that does not contain any whitespace.

You may assume that individual tokens in a rule are separated by a single space, and that there will be no outer whitespace surrounding a given rule or token.

Your generateGrammar function will perform two major tasks:

- read an input file with a grammar in Backus-Naur Form and turns its contents into a data structure

- randomly generate elements of the grammar (recursively)

main function supplies you with an input file stream to read the BNF file. Your code must read in the file's contents and break each line into its symbols and rules so that it can generate random elements of the grammar as output. When you generate random elements, you store them into a Vector to be returned. The provided main program loops over the vector and prints the elements stored inside it.

Part 1: Reading the Input File

For this program you must store the contents of the grammar input file into a Map. As you know, maps keep track of key/value pairs, where each key is associated with a particular value. In our case, we want to store information about each non-terminal symbol, such that the non-terminal symbols become keys and their rules become values. Other than the Map requirement, you are allowed to use whatever constructs you need from the Stanford C++ libraries. You don't need to use recursion on this part of the algorithm; just loop over the file as needed to process its contents.

One problem you will have to deal with early in this program is breaking strings into various parts. To make it easier for you, the Stanford library's "strlib.h" library provides a stringSplit function that you can use on this assignment:

Vector<string> stringSplit(string s, string delimiter)

This function breaks a large string into a Vector of smaller string tokens; it accepts a delimiter string parameter and looks for that delimiter as the divider between tokens. Here is an example call to this function:

string s = "example;one;two;;three";

Vector<string> v = stringSplit(s, ";");

// now v = {"example", "one", "two", "", "three"}

The parts of a rule will be separated by whitespace, but once you've split the rule by spaces, the spaces will be gone. If you want spaces between words when generating strings to return, you must concatenate those yourself. If you find that a string has unwanted spaces around its edges, you can remove them by calling the trim function, also from "strlib.h":

string s2 = " hello there sir "; s2 = trim(s2); // "hello there sir"

Part 2: Generating Random Expansions from the Grammar

As we mentioned, producing random grammar expansions is a two-step process. The first step, which we’ve just outlined, requires reading the input grammar file and turning it into an appropriate data structure (non-recursively). The second step requires your program to recursively walk that data structure to generate elements by successively expanding them.

The recursive algorithm that your program will use to generate a random occurrence of a symbol S should have the following logic:

- If S is a terminal symbol, there is nothing to do; the result is the symbol itself.

- If S is a non-terminal symbol, choose a random expansion rule R for S, and for each of the symbols in that rule R, generate a random occurrence of that symbol.

For example, the example grammar given in the Problem Description above could be used to

randomly generate an <s> non-terminal for the sentence, "Fred honored the green wonderful child", as shown in the following diagram.

If the string passed to your function is a non-terminal in your grammar, use the grammar's rules to recursively expand that symbol fully into a sequence of terminals. For example, using the grammar on the previous pages, <np> might potentially expand to the string "the green wonderful child".

Generating a non-terminal involves picking one of its rules at random and then generating each part of that rule, which might involve more non-terminals to recursively generate. For each of these you pick rules at random and generate each part, etc.

When you encounter a terminal, simply include it in your string. This becomes a base case. If the string passed to your function is not a non-terminal in your grammar, you should assume that it is a terminal symbol and simply return it. For example, "green" should just cause "green" to be returned (without any spaces around it).

Special cases to handle: You should throw an exception if the grammar contains more than one line for the same non-terminal. For example, if two lines both specified rules for symbol "<s>", this would be illegal and should result in the exception being thrown. You should throw an exception if the symbol parameter passed to your function is empty, "". You can do this by calling the built-in throw function, which takes a string parameter containing a description of the error that occurred. The throw function will terminate the program.

Testing: The provided input files and main may not test all of the above cases; it is your job to come up with tests for them.

Your function may assume that the input file exists, is non-empty, and is in a proper valid format otherwise. If the number of times passed is 0 or less, return an empty vector.

Implementation Details

The hardest part of this problem is the recursive generation, so make sure you have read the input file and built your data structure properly before tackling the recursive part. Loops are not forbidden in this part of the assignment. In fact, you should definitely use loops for some parts of the code where they are appropriate. For example, the directory crawler example from section uses a for-each loop. This is perfectly acceptable; if you find that part of this problem is easily solved with a loop, please use one. In the directory crawler, the hard part was traversing all of the different sub-directories, and that's where we used recursion. For this program, the hard part is following the grammar rules to generate all the parts of the grammar, so that is the place to use recursion. If your recursive function has a bug, try putting a cout statement at the start of your recursive function to print its parameter values; this will let you see the calls being made. As a final tip: look up the randomInteger function from "random.h" to help you make random choices

between rules.

Possible Extra Features

Consider adding extra features to these programs if you'd like. Note that since we use automated testing for part of our grading process, it is important that you submit a program that conforms to the preceding assignment spec, even if you do extra features. You should submit two versions of your program for extensions: the provided one without any extra features added, and a second one with extra features. Please distinguish them by explaining which is which in the comment header. In the comment header, please also list all extra features that you worked on and where in the code they can be found (what functions, lines, etc. so that the grader can look at their code easily).

Here are some example ideas for extra features that you could add to your program.

- Dynamic Programming There's another way to avoid making multiple recursive calls called dynamic programming that's equivalent to memoization, but uses iteration rather that recursion. Look up dynamic programming and try coding this function up both ways. Which one do you find easier?

- Fractals: Although this assignment is all about recursion, if you're up for a challenge, try replacing the recursive version of your code to draw an order-n Sierpinski triangle with an iter- ative function that draws an order-n Sierpinski triangle. There are also a ton of other cool fractal designs that you can create using recursion. Go investigate and see if you can find anything else cool to code up!

-

Robust grammar solver:

Make your grammar solver able to handle files with excessive whitespace placed between tokens, such as:

" <adjp> ::= <adj> | <adj> <adjp> "

- Inverse grammar solver: Write code that can verify whether a given expansion could possibly have come from a given grammar. For example, "The fat university laughed" could come from sentence.txt, but "Marty taught the curious students" could not. To answer such a question, you may want to generate all possible expansions of a given length that could come from a grammar, and see whether the given expansion is one of them. This is a good use of recursive backtracking and exhaustive searching. (Note that it’s tricky.)

- Other: If you have your own creative idea for an extra feature, go for it! Feel free to ask your SL and/or the instructor about it.

FAQ

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Q: I'd like to write a helper function and declare a prototype for it, but am I allowed to modify the .h file to do so?

- A: Function prototypes don't have to go in a .h file. Declare them near the top of your .cpp file and it will work fine.

- Q: What does it mean if my program "unexpectedly finishes"?

- A: It probably means that you have infinite recursion, which usually comes when you have not set a proper base case, or when your recursive calls don't pass the right parameters between each other. Try running your program in Debug Mode (F5) and viewing the call stack trace when it crashes to see what line it is on when it crashed.

- Q: The spec says that I need to throw an exception in certain cases. But it looks like the provided main program never goes into those cases; it checks for that case before ever calling my function. Doesn't that mean the exception is useless? Do I actually have to do the exception part?

- A: The exception is not useless, and yes you do need to do it. Understand that your code might be used by other client code other than that which was provided. You have to ensure that your function is robust no matter what parameter values are passed to it. Please follow the spec and throw the exceptions in the cases specified.

- Q: How do I spot nonterminal symbols if they don't start/end with "<" and ">"?

- A: The "<" and ">" symbols are not special cases you should be concerned with. Treat them as you would any other symbol, word, or character.

- Q: Spaces are in the wrong places in my output. Why?

- A: Try using other characters like "_", "~", or "!" instead of spaces to find out where there's extra whitespaces. Also remember that you can use the trim function to remove surrounding whitespace from strings.

- Q: How do I debug my recursive function?

- A: Try using print statements to find out which grammar symbols are being generated at certain points in your program. Try before and after your recursive step as well as in your base case.

- Q: My recursive function is really long and icky. How can I make it cleaner?

- A: Remind yourself of the strategy in approaching recursive solutions. When are you stopping each recursive call? Make sure you're not making any needless or redundant checks inside of your code.

- Q: When I run expression.txt, I get really long math expressions? Is that okay?

- A: Yes, that's expected.

- Q: Can I use one of the STL containers from the C++ standard library?

- A: No.

- Q: I already know a lot of C/C++ from my previous programming experience. Can I use advanced features, such as pointers, on this assignment?

- A: No; you should limit yourself to using the material that was taught in class so far.

- Q: Can I add any other files to the program? Can I add some classes to the program?

- A: No; you should limit yourself to the files and functions in the spec.