1994 Project Reports | Contents | Previous | Next | Home |

Tactile transducers to replace lost touch sensation

Eric E Sabelman, PhD; Greg TA Kovacs, MD, PhD; Vincent R Hentz, MD; Joseph M Rosen, MD; Chris Kurjan, MS; Paul Merritt, MS; Greg Scott, MS; Adam Gervin, MS; Star Teachout, MS

Problem - Loss of touch and pressure sensation may occur as a result of spinal cord injury, brachial plexus or CNS trauma, diabetes, or Hansen's disease. Even if muscle function is retained, this sensory deficit interferes with fine hand control of grasp and pinch forces, and the lack of protective sensation increases the risk of pressure sores in other areas of the body.

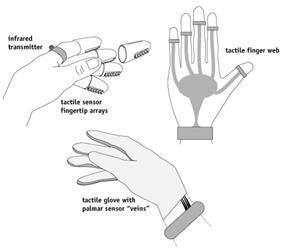

In order to restore some sensory communication and protective sensation via a closed-loop servocontrol mechanism, we have undertaken two projects: Transducer evaluation for external fingertip mounting (Figure 1), and the design of an implantable fingertip touch sensation prosthesis. In the former, we studied the potential of various sensor technologies to substitute for finger pressure and shear force detection, by testing under laboratory conditions and also using clinical tests commonly applied to the human hand. In the latter, we are studying preferred anatomical sites for touch sensors, constructing prototype implantable miniature sensors, and building large-scale circuits for powering and transmitting signals from implanted sensors.

Figure

1. Concepts for externally mounting sensor arrays on the hand.

Figure

1. Concepts for externally mounting sensor arrays on the hand.

Significance - Currently, the motor activities of people who have impaired sense of touch are less effective, even if motor function is present or replaced by a powered prosthesis. Powered prosthesis users are burdened with the task of visually estimating the forces needed to grasp an object without damaging it, and typically must maintain eye-contact throughout the manipulation procedure. Proposed closed-loop controls would lessen if not eliminate this burden, but require miniature sensors to provide information to the control system. Furthermore, new sensor arrays could yield more accurate measurement of a patient's tactile sensitivity, resulting in superior clinical assessment, and could possibly be used for more accurately fitting prostheses to the body.

Background - Since most touch sensors have been developed for robotic applications in automated manufacturing, they have not been compared directly with normal and impaired human sensory capabilities. Existing clinical techniques for assessing tactile perception in patients have not previously been applied to sensory transducer arrays. Since some clinical tests are qualitative (e.g., texture discrimination), the tactile transducers are also subjected to a battery of quantitative tests (e.g., single and two-point pressure discrimination).

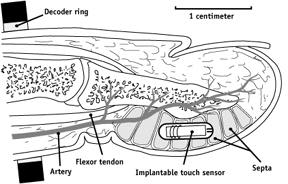

Hypothesis - The anatomy of the fingertip evolved to provide direct connection between tactile sensation and the brain - the central controller. These sensors are not randomly distributed, but hypothetically occur exactly where they are needed - where the aspects of touch they respond to are most easily detected. The central premise of this research project is that otherwise non-directional artificial sensors could detect the direction of stimuli if placed in these privileged sites (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Location of implanted touch sensor within fingertip. Four to

eight sensors would lie side-by-side with sensitive ends staggered to localize

stimuli to +/- 4 mm.

Figure 2. Location of implanted touch sensor within fingertip. Four to

eight sensors would lie side-by-side with sensitive ends staggered to localize

stimuli to +/- 4 mm.

Approach - In the first phase of this project we: 1) obtained and

measured properties of isolated silicon, resistive, capacitative, optical,

hydrogel and Hall effect sensors; 2) tested the sensors using clinical

assessment tools such as the Semmes-Weinstein, static and dynamic two-point

discrimination and texture identification, for comparison with normal and

minimal human sensation; and 3) tested the sensors on a mechanical simulated

finger equipped with actuators for exerting known forces against a fixed

baseplate.

Results from the first phase indicated that sensors located on the hand's grasping surfaces would probably interfere with the process of grasp and manipulation. To eliminate this interference, it was suggested that sensors be placed under the skin in isolation from the hand and the object being manipulated. State-of-the-art implantable sensors have advanced to the point that small glass-encased transducers can be injected through a large-bore hypodermic needle.

Status - A principal finding of the first phase was that commercially available sensors were not available or were inadequate in dimensions or sensitivity. Sensors of various types were constructed at larger scale than ultimately required for fingertip mounting and tested for their ability to detect absolute and relative magnitudes of perpendicular and shear (tangential) force.

A new type of sensor was based on measuring variations in magnetic field strength and direction as a magnetic source is displaced in response to external forces. As is the case with other transducers that rely on deformation of a compressible layer, the sensor transfer function depended upon the material properties of this layer. Shear loading produced very little evidence of hysteresis, repeatable responses, and a 500 millivolt range over which to detect tangential motion.

In the second phase of this project, we are conducting two parallel investigations: 1) to quantitatively describe the anatomy of the fingertip pulp, in order to define the optimum transducer placement; and 2) to design and evaluate preliminary concepts of an implantable pressure sensor.

Full-scale models of cross-sectional anatomy were constructed, and a relationship between (simulated) septa elasticity and point load force distribution on the finger surface was tested. Measured pressure increased in proportion to proximity to the tip of the force gauge indentor and compliance of the septum wall. The interseptal pressure measurement apparatus used at 5 sites within simulated or cadaver fingers is autoclavable and could potentially be used on a living (anaesthetized) finger.

We are currently testing the anatomical hypothesis by partial dissection of cadaver fingers. This anatomical study will also confirm that sensors of feasible dimension can fit within the space available in a fingertip. Whole- mount preparations and thin-section histology with and without a mockup transducer have been included to determine the transducer's effect on surrounding tissues.

The transducer design will combine state-of-the-art technologies from implantable, ingestible, and catheter-tip sensors, and silicon microfabrication techniques at the Stanford Center for Integrated Systems. The enlarged working circuit (which includes the pressure sensor, amplifier, FM modulator and antenna), demonstrated inductive power transmission. Other power input and signal output transmission modes will be explored, including direct wiring, radio frequency and infrared.

Republished from the 1994 Rehabilitation R&D Center Progress Report. For

current information about this project, contact

Eric Sabelman.