From Griffithiana no. 71, 2001

|

|

| Norma Talmadge [This picture was not in the original article, it replaces a closeup of a smiling Talmadge with her hair down provided by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences] |

The name Norma Talmadge still brings a smile to the faces of people old enough to remember her films. One of the most popular and beloved stars of the silent film era and number one female star at the box office for three years running, Talmadge was widely regarded as the finest actress of her time by her fans, and with a few notable exceptions, by critics. 1 Yet, since the coming of sound her reputation has fallen precipitously. While her name frequently turns up in film histories, there is little serious attention given to her career; and most of that attention tends to be negative, denigrating both her films and her acting ability. With the films long out of circulation, there has been little opportunity for a reassessment, even though recent film writers reviewing contemporary source materials recognize the anomaly of the widely divergent opinions.2

Unlike many now obscure stars, however, a considerable number of Talmadge films have survived, most notably in a recent acquisition by the Library of Congress.3 Thus, an opportunity presents itself for a long overdue critical reassessment. This article will analyze her screen persona and acting style, explore contemporary reception, highlight some of her screen performances, and propose theories about her post career critical downfall.

Since Norma Talmadge is largely a mystery for modern viewers, a description of her screen persona is a useful introduction. Seeing Norma Talmadge for the first time in films from her prime is something of a surprise. Far from the regal, tear-stained diva one would expect from post-career descriptions and from her rather stuffy still photos, her screen persona is basically that of a charming and unpretentious young woman, full of warmth, and often humor. This seems to be the core personality to which she returns in moments of repose, and is evident throughout her career, from her early Vitagraph shorts into her final talkies. In her early films she girlish and vivacious; as she matured she became more serene and dignified, but always had a ready smile or laugh when the occasion permitted. In some films she may display this persona for most of the film, as in the romance Smilin' Through (1922). However, she was renowned for her versatility and command of emotional roles, so those moments of repose may be few and far between in many of her films, and in some may never appear at all. Often we see her tensed in some sort of emotional turmoil. Then the other sides of Norma Talmadge's persona appear. There are the fiery and defiant Normas of Passion Flower (1921) and Song of Love (1923) and the terrorized Normas of The Safety Curtain (1918) and the opening of Within the Law (1923). In contrast, there is the reserved and watchful criminal mastermind of the remainder of Within the Law, the haughty noblewoman of Ashes of Vengeance (1923), the coquettish dancer of The Dove (1928), the tired but hopeful streetwalker of Woman Disputed (1928) and even the Ethnic Other ingenues of Forbidden City (1918) and The Heart of Wetona (1919). Often she displays several sides to a character in a single film. In The Safety Curtain she cynically dismisses a stage door Lothario, cringes before her violent husband, pulls herself together to present a smiling professional face to a stage audience, plays with her animals and new husband like a rambunctious child, and charms and wheedles her husband's colleagues.

Such variety and versatility is often considered a problem for constructing a star persona, since the audience may have trouble identifying what to expect of a star from film to film. Familiarity is a prerequisite for the kind of affection a star generates in his or her fans. Her characterizations vary from film to film, yet in a way they all remain the same. Talmadge gives all of these characters a sympathy, humanity, and warmth characteristic of her core screen personality that comes through despite the emotional turmoil. Her open geniality is quite different from the surface brittleness of the early 30s drama queens or the fierce and faintly neurotic edge of later dramatic stars such as Davis, Crawford, or Stanwyck. Her seemingly genuine ease and charm creates a sense of intimacy with the audience. This enabled them to imagine that they were seeing a real woman, and a likable one at that. They could feel that they knew and could identify with her, both through the changes in a single film and their cumulative viewing experiences of her various roles though her career.

|

|

| Publicity photo of Talmadge with a pet pomeranian. Her dogs often appear in her publicity photos, and occasionally in her New York based films (Author's collection) |

In enacting these parts, Norma Talmadge commands a remarkable variety of expressions through an extraordinary control of her facial muscles and use of her body. She is an extroverted performer, more active than many silent actors and virtually all sound ones, using her face and body to make explicit internal emotional states and thought processes, yet making it seem both natural and spontaneous. The key to her mature performance style is her eyes. Large with subtly mobile brows, her eyes are alert, thoughtful, and very expressive. Moods flit across her face with a slight widening or narrowing of the eyes, a glance, a quick knitting or raising of the brows, lowering of the lids, or a sudden welling of tears. The latter is a feature for which she was particularly remembered; sometimes blinking the tears back with a forced smile, sometimes letting them tumble down her cheek. Contrary to modern descriptions, the tears are not a predominant feature of her films. Sometimes one has to look fast to see them; they come and go quickly as do her other moods. The eyes are often enhanced at the height of her career with a "wet look" eye makeup, giving her a somewhat misty-eyed appearance. This was replaced in her later film appearances by a Garboesque style makeup with V-shaped liner at the outer corner of her eyes, making them look even larger and more liquid. This along with a wider mouth adds to a more mature and worldly impression. This is startlingly apparent in Woman Disputed, where we first see her in a very dark and exaggerated version of this later makeup as a streetwalker made up for business. Yet even with this, she can suddenly soften her eyes in response to another character, signaling to the audience that the character is a kind and sympathetic woman despite her hardened exterior. The rest of her face and body are also quite expressive. She has a radiant smile which is seen quite frequently when the plot allows. She also has a variety of amusingly wry expressions, usually involving tilting her head and suppressing an overt smile, but dimpling her cheeks. She registers determination or defiance with an upward thrust of her chin. The dejected stoop of her shoulders expresses the overwhelming weight of whatever is troubling her at the moment in the film. In moments of shock or alarm, her hand may be raised slightly, as though suspended in indecision, her fingers tensed, almost clawlike. Then she may clench it into a fist and raise it near her mouth in concentration or sorrow.

|

|

|

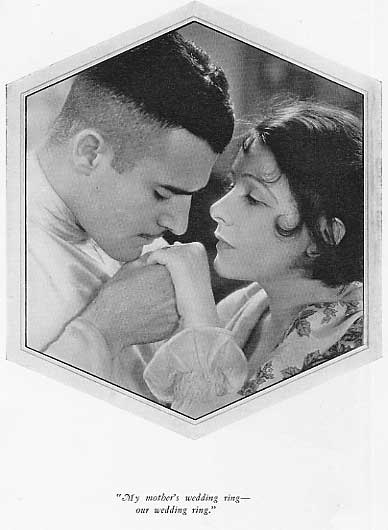

[This picture was not in the original article, it replaces a similar picture (same photo session) provided by the editors of Griffithiana. It had the caption "Gilbert Roland, Norma Talmadge in Camille, 1927. Postcard"] |

The particular expressions of a performer also form a point of identification for the audience, and become a familiar feature and anticipated pleasure of viewing a star vehicle (think of Bette Davis' bulging eyes and aggressive stride for a later generation of viewers). Paul Rotha description of her as "looking slightly perplexed and muzzy about the eyes" is a caricature of some of Talmadge's characteristic expressions.4 Frequent use of close-ups and medium close-ups bring her face in better view of the audience. Passion Flower is structured around medium close-ups of Talmadge performing lightning-fast changes from relaxed happiness to tense hatred as she finds herself being observed by her despised stepfather. Charles Rosher's luminous close-up of Talmadge fighting back tears as her lover fails to return in Smilin' Through are among the most memorable features of that film.

Roberta Pearson used the term "gestural soliloquy" to describe a sequence of gestures used by an actor in a solo scene to indicate emotional catharsis or trace thought processes.5 Talmadge has many of these in her films, though they tend to be as much facial soliloquies. In the opening of The Lady (1925), she passes from comfortable conviviality to radiant, then tearful reminiscence, to an ironic smile, back to moist-eyed memory, all in less than half a minute. In a memorable scene from Secrets (1924), she shoots an intruder and stands with one hand in her hair and her mouth in an open grimace, eyes wide with shock and terror. Leaving her body still, she changes to an expression of joy and relief as the other intruders flee, then suddenly drains of all expression as she remembers her dead child. Greg M. Smith has noted her predilection for scenes involving deception of some sort. 6 She often shows one face to the other characters in the film, while showing the audience the character's "true" feelings. This diegetic "acting" serves as a particular showcase for a performer who is skilled at displaying rapidly changing or conflicting emotions, and would also have enhanced her popular reputation as an actress. Indeed, she is at her best when her directors let the camera linger on her as she goes through her emotional paces, and her most satisfying films are those which give her plenty of space to perform. For these reasons, Talmadge's still photos fail to convey an accurate impression of her. She must be seen in motion in order to grasp her cinematic appeal.

Any sort of description such as this which tries to break down specific movements and expressions has the effect of making them sound stereotyped and exaggerated, but seen on the screen the cumulative effect of Talmadge's performance characteristics is one of great sensitivity and naturalism. She is one of the masters of silent screen performance style.

These observations are congruent with contemporary descriptions of Talmadge. Adele Rogers St. Johns called her "our one and only great actress."7 Bernard Sobel admired her "remarkably accurate response to original womanly impulses."8 Gilbert Seldes observed that by the mid teens "Norma Talmadge was playing the roles of entirely credible women in an intelligent way."9 Clarence Brown called her "the greatest pantomimist that ever drew a breath." F. Scott Fitzgerald remembered in Tender is the Night: "Norma Talmadge must be a fine, noble woman beyond her loveliness. They must compel her to play foolish roles…"11 Robert E. Sherwood, who generally deplored her films, said "Miss Talmadge is a good actress. She has power, she has poise and she possesses a delicate subtlety of expression. But her undeniable talent had been guided into false channels." They were not the only ones accusing her of coasting in vehicles unworthy of her talent. Fans seemed to have had high opinion of her acting ability, judging from the letters in Photoplay, consistently holding her up as a benchmark for other performers. 14

What was it that made Talmadge such a huge star? Second in popularity only to the unique and already anachronistic Pickford, Talmadge dominated the 1920s as the epitome of modern womanhood as no star since has done. It could not have been merely her acting. There were as good or better actresses on screen; Gish springs immediately to mind. While Gish's artistry was universally acknowledged, she was perceived as rather more highbrow in appeal and was more admired than loved by the public. Some fans thought Talmadge superior to Gish in her acting because she played a wider range of characters. Swanson and briefly Negri approached her in popularity without displacing her. An exciting actress, Negri's foreigness was always foregrounded in her publicity, and reports of her offscreen histrionics soon alienated fans. The cannier Swanson, a homegrown exotic, had a larger-than-life personality that bordered on the transgressive. She played, not a model of ideal womanhood, but either a privileged or ambitious woman who would be put firmly in her place by the end of the film. A more successful challenge to Talmadge's position came at the end of the 1920s with the appearance of Greta Garbo. Ironically, though their personalities are completely different, there was a similarity in their expression and technique, as well as a certain facial resemblance at the time their careers overlapped, accentuated by their make-up. This similarity was noted in Garbo's early career. Irene Selznick recalled Louis Mayer's reaction to Gösta Berling's Saga as follows: "Look at that girl! There's no physical resemblance, but she reminds me of Norma Talmadge-her eyes. The thing that makes Talmadge a star is the look in her eyes."15 In her review for Talmadge's Camille (1927), Irene Thiriers noted "at times resembling in the intensity of her performance, Greta Garbo, she has warmth for Garbo's coldness and tenderness for Garbo's trickiness." 16 As fate would have it, Talmadge faded from the scene and Garbo moved into her niche, specializing in similar glossy exotic melodramas, remaking one Talmadge film (Camille) and being rumored for another (La Duchesse de Langeais, the original source for The Eternal Flame (1922)). She even assumed her mantle as the screen's greatest actress and an updated exemplar of the ideal woman.

Was it "the look in the eyes" that Mayer spoke of that made Talmadge a star? That indefinable quality is apparent in many of her films. But there are other factors which can be discussed more objectively. Certainly Talmadge and her husband and producer Joseph Schenck were expert in using the publicity apparatus of Hollywood to keep her in the public eye and in reading public taste to position her into a favored type.

Smith has located Talmadge within the post World War I discourse of the New Woman-a woman confident, competent, and appropriately sexually aware, yet who chooses love, marriage and subordination to her husband.17 Indeed, this is the thrust of much of her publicity material which saturated the fan magazines, presenting her as a nice young woman with working class roots who had worked her way up and made it big as a star, vastly wealthy, but at the same time reassuringly sweet and unspoiled, with a happy marriage to a powerful producer and a close knit family life.18 The actual truth of her private life may have been different and is in any case irrelevant. This carefully cultivated image was suspiciously close to her screen persona. When Adela Rogers St. John said "Norma Talmadge is an extremely real, extremely human and unspoiled girl, and I like her and so would you," she was just stating what the public expected to hear. 19 While reports circulated about her wealth and business activities and praised her acting skill and hard work, her own public statements frequently denied her agency in her success. "My success has absolutely nothing to do with me," she told Bernard Sobel in 1921, and "I've never really planned anything … Things happened to me" she said to an interviewer in 1931. 20 Her working relationship with her producer/husband was well publicized, but many of the fan magazine columns will also toss in a reference to "Mrs. Joseph Schenck," assuring the public that at least in private life she conformed to societal expectations of subordination to her husband.

Another element of her public presentation, as with many other female stars, is her clothes. This is an important, but often unspoken element of a female audience's viewing pleasure. Movie producers realized its importance, and Talmadge excelled at this element of star apparatus. Between 1917 and 1921, Talmadge's productions were based in New York City, with better access to New York and London dress designers. In her modern dress films she usually wears the chic, elegant clothes which she shows off to great advantage. Her costumes in the Teens were often uncredited designs by New York couturier Madame Francis. 21 Her Hollywood designers included Walter J. Israel, Clare West, Sophie Wachner, and Alice O'Neill. Her screen costumes and budgets for costumes were reported as part of her publicity. 22 In one amusing story reported to American Magazine, she exhorted a group of extras who were reluctant to enter a slime pit by wading in herself. The reporter did not fail to note that she was wearing a $5,000 Lucile gown at the time.23 By 1920 she was already considered the best dressed woman in pictures. 24 In May 1920-1921 she (or more likely someone operating under her name) did a stint as the fashion editor of Photoplay, contributing articles on various fashion topics, such as "Clothes for Special Occasions," "Launching the Winter Mode," and "Wear America First." Offscreen Madame Francis was still a favorite, but she also appeared in clothes by Howard Greer. Stars were also on duty offscreen, and public events were opportunities to be on display for the fans. Pictures of her personal wardrobe circulated publicly in the fan magazines, which provided endless descriptions of what she wore to various comings and goings around Hollywood. In 1928 for her radio debut with other United Artists stars on the eve of talking pictures, she chose as her topic "Fashion and the Films." 25

This complex interplay between screen, publicity and fan is largely lost on modern viewers, but it was an important part of contemporary reception. Fan magazines reported incessantly on her clothes and hairstyles, her investments, her diet, her house, her vacations. Publicity and experiences of previous performances fed audience expectations of what they would see on screen, and what they saw on screen created expectations about the real person behind the screen, which were met by publicity conforming to those expectations.

Modern sources usually identify Talmadge as a star appealing mainly to women. Since women were the majority of the audience's members, this is probably true of most stars of the time. Yet her vast popularity, at least in her early years and at the height of her career, suggests that her appeal was more widespread, and the New Woman would have been appealing to both sexes. While women would have been attracted by a stories focusing on a woman as the main character and female audiences were cultivated by the publicity and fashion, men may have also found her appealing as a attractive and passionate young woman, yet wholesome and reassuringly feminine. Perhaps audiences identified with this working class girl who had made good and had grown up on screen before them. Perhaps they imagined that she behaved as they would like to think they would behave if they were rich and famous. Her apparent modesty and decorous public behavior despite her fame and glamour were reassuring in an era of star scandals and public concern about the morality of films and film players in an era of rapid social change.

During Talmadge's screen career many magazine articles circulated concerning her early career at Vitagraph. One often repeated story described her as slow to learn her craft. Reportedly she was about to be fired for her ineptitude,when she was championed and mentored by veteran actor and Vitagraph's biggest male star Maurice Costello, who helped her develop into one of Vitagraph's most popular players. 26 However these stories may have been intended to function in the public discourse of star publicity and fan magazines, and whatever the truth of the individual details, the general thrust of the story is quite plausible. In her Vitagraph films, An Old Man's Love Story (1913) or The Helpful Sisterhood (1914), for example, she is a pretty teenager with an winning dimpled smile and a particularly raucous Brooklyn-schoolgirl laugh. Though an attractive performer, she is often visibly immature and inexperienced. There is nothing special to mark her as a major star.26a

By 1916 she was starring in a series of movies for Triangle, and there had been some progress in her abilities from the Vitagraph days. Here she is still baby-faced, but has acquired more poise before the camera, allowing her natural charm to come through. She is most at ease in comedy,and her quicksilver expressions and sense of fun are displayed to advantage in her delightful performance as The Social Secretary (1916). In drama, however, she still stiffens up when called upon to express extremes of emotion, and her responses are exaggerated and unconvincing. In some scenes one sees the two modes oscillating. For example, in Going Straight (1916) she has a scene where she sits on the bed and reads a letter from her jailed husband. She thrusts the letter down and her chin up with her eyes pressed tightly closed, looking every bit the inexperienced girl trying hard to act. Yet a moment later she glances at the chest of drawers and goes over to take out some baby clothes. Perhaps distracted from her histrionics by the presence of a bit of business to perform, the stiffness suddenly melts away as she pensively lifts out the objects and looks into the distance. Here, finally, is a glimmer of the future.

In her early independent films, she is still more of a personality than an actress. She was beginning find favor with the critics at this time, particularly after her spectacular success in Panthea (1917). Compared to her later performances, Poppy (1917) displays more energy than depth in her playing, but she is reasonably convincing and quite appealing. Julian Johnson of Photoplay praised Talmadge's performance in Poppy, saying that she "passes perfectly from short-frocked, barbarous childhood to slightly satiric, elegant maturity," and that "there is not another camera woman who could so contrive this character's long range and unexpurgated catalog of every female emotion." 27

Her dramatic ability steadily improved through the late teens. She became confident and self-assured before the camera, with the subtle mobility of feature and apparent naturalism for which she was famed. She had lost weight, adding definition to her features and losing that babyish facial quality, and emerged as a beautiful and vibrant young woman. Her role in Safety Curtain is among her best performances of this period as an abused child-woman with a strong instinct for survival. However, many of her characters from this period seem cut from the same cloth, even in double roles there is often little differentiation between the two characters, as in The Law of Compensation (1917).

|

|

| The Eternal Flame (1922). Talmadge menaced. (Bison Archives / Marc Wanamaker) |

By 1920 a transformation had taken place. From this point on, she was considered an exemplar of fine screen acting. Yes or No (1920), her most interesting double role, shows a much greater maturity in her acting. Talmadge is able to clearly differentiate her two roles in the film. Her rich woman (in a blond wig) is snappish and spoiled, and unsympathetic until her final scenes. The tenement wife is one of her finest characterizations. In a role which could have been saccharine, she combines just the right doses of good humor, irritation, and affection in a portrait of a strong and sensible woman. Another fine performance is in Herbert Brenon's The Sign on the Door (1921) an entertaining crime drama in which she ranges from playful silliness to utter panic as a young woman who winds up locked in a room with a dead man.

Her acting continued to develop throughout her career, gradually changing from the youthful vivacity and passionate intensity of her earlier independent productions to a more relaxed and quieter manner, which she displays in films from her prime. Among her gallery of fine perfomances from this period are certain standouts. Robert E. Sherwood thought The Eternal Flame the finest role of her career, enabling her to "range from unassailable virtue, to sly deviltry, from blank innocence to cynical sophistication, from tyrannical dominance to abject submission, and from bored worldliness back to spiritual regeneration." 28 Even with two reels of the film lost, the remains of her performance are impressive. In the ultra-romantic Smilin' Through her performance looks deceptively easy, and she radiates graciousness and charm in both roles as a modern girl and her 19th century ancestor. She is particularly fine in her death scene, in which she sinks to the ground and dies quietly in her fiancé's arms, her eyes losing focus and fading as he hugs her to his breast.29 Within the Law reachest its highest emotional pitch in the early part of the film with Talmadge as a bewildered and terrified shopgirl wrongly convicted of theft. Toughened up by a stint in prison and a suicide attempt, the character is portrayed in the rest of the film as cool and unflappable on the surface, but honest and generous underneath. Though Talmadge's performance lacks the satisfying rage of Joan Crawford in the 1932 remake Paid, her softer conception of the role makes the plot twist at the end less implausible.30

|

|

|

Talmadge in a fashion pose. The caption reads: "Norma Talmage as she appears in a scene from Graustark, wearing a gorgeous and unique evening gown which was made from a Spanish shawl over three hundred years old. It is most effective worn over a rich slip of black satin." (Marc Wanamaker / Bison Archives) |

In her book A Woman's View, Jeanine Basinger describes three types of female stars: The "unreal," the "real"-one who is supposed to be like the audience in some way and is a star of general appeal, and the "exaggerated." 31 The "exaggerated" type is always a major star in late career, usually having begun as a "real" type, who has evolved into a mixture of real and unreal, and whose overpowering presence dominates a film. These women could either be excessively neurotic or excessively noble, and are often identified as "actresses" rather than mere "movie stars." This type of star usually appeals chiefly to women, particularly older women. The phenomenon is not yet well documented in silent films, where the advent of sound forced a premature end to many careers, but the pattern seems to hold true for Norma Talmadge. Her acting was praised for its naturalism and she projected herself as a "real" woman, but in her late career she moved into a more rarefied realm, portraying chiefly entertainers and courtesans, with a prostitute and a princess thrown in to vary the mix. Her persona gradually acquired a more remote, inward quality. In the most memorable films from this period she played women who nobly sacrificed and suffered, sometimes aging, sometimes losing their lives. Sacrifice and suffering had always been an element of her films as they were for many other actresses, but somehow in these late films her qualities became distilled- the sum of all of the Norma Talmadges of the past. As Basinger points out, a star can become identified with a particular type of role, even though it did not actually constitute a majority of the roles she played. 32 It was Suffering Norma that her fans and detractors remembered, becoming her legacy in film history.

Talmadge found her most sympathetic director in Frank Borzage, and together they made her two finest films. Though she had played old women on occasion in her Vitagraph days, she was quite remarkable in Secrets as the elderly woman remembering scenes from her marriage, and deftly alters her performance style to match the distinctively different tone of each of the episodes from her life. In The Lady, Talmadge gives a beautiful performance as a Cockney music hall performer turned protective mother turned middle aged bartender, remembering how she was forced to give up her child. For Henry King, Talmadge gave a mature and deeply felt performance in an emotionally arduous role in Woman Disputed as a not-so-hardboiled former prostitute who can't escape her past.

Despite her reputation for versatility, Talmadge did have occasional misfires. Evil women are not her strong suit, and her portrayal of a notorious cabaret dancer in Ghosts of Yesterday (1918) is entertainingly hyperactive, but not very convincing. Though she reportedly enjoyed playing various ethnic groups and nationalities, presumably to showcase her versatility, her efforts to conform to those stereotypes seems to inhibit rather than inspire her performances.33 This is particularly noticeable in Forbidden City. With her eyes immobilized by reportedly rather painful makeup in a role as a Chinese woman, it is interesting to see how Talmadge's performance style is hindered. Fortunately, in her other role as the daughter she has nothing to show of her mixed race background except some fishtail eye liner, and the performance picks up considerably. As a the Indian maiden in Heart of Wetona, Talmadge makes the character of seem irritatingly slow-witted, with her trademarked "thinking" expressions slowed to a crawl. Her more tempestuous ethnics-the Arab dancer in Song of Love and the Hispanic girl of The Dove--have an element of parody, as though Talmadge is self-conscious and rather amused by the masquerade. This is not disturbing in the endearingly absurd Song of Love. In fact, the New York Times reviewer was beside himself with excitement over her relatively scanty costumes and her "tempestuous, brazen" personality. 34 Perhaps he never thought of her as sexy. On the other hand, in The Dove her distracted and self-amused performance leaves the film dominated by the grotesque grimacing of Noah Beery. 35 Variety noted that "under suppressed emotion Miss Talmadge is not as impressive as when turning on the works." 36 In Graustark (1925) Talmadge had a undemanding role as a princess which she should have been able to do in her sleep. Girlish vivacity did not come to her as naturally as it once did, and she is rather forced in the lighter parts of the picture, with excessive jumping about and clasping of hands. Her dramatic scenes are largely confined to reaction shots of her closing her eyes, leaning back her head, and clutching herself in various places. It is a very odd performance; perhaps she and director Dimitry Buchowetzki could not find common ground. Kiki (1926) is more controversial. Director Clarence Brown admired her performance, saying "she was a natural-born comic; you could turn on a scene with her and she'd go on for five minutes without stopping or repeating herself." 37 The reviews were very favorable as well. It was a tricky role, one of irrepressible youth seemingly more suited to Clara Bow. Talmadge's offbeat performance, part otherworldly dreamer, part Pickfordesque roughneck, seems more suggestive of mental illness than youthful high spirits. To this viewer, anyway, it really doesn't quite come off. 37a

Looking back at Talmadge's silent films, one regrets that she didn't have better material to work with. Many had trivial and banal stories, though no more so than most of her contemporaries. Robert E. Sherwood was correct when he observed that: "she had become a box-office star, devoting herself to standard, stereotyped "emotional" roles which permitted her to wear a given number of fashionable gowns, and to occupy a given number of close-ups." 38 Her much touted versatility didn't include the opportunity to try truly daring parts: characters who were unsympathetic, neurotic, or perverse. Her films were usually cautious and carefully crafted with an eye to the box office. While she certainly appeared in a number of these routine films, her performance gives them whatever distinction they have. When she did have challenging roles she rose to the occasions, giving performances of great sensitivity and depth.

In 1928, Talmadge and other United Artists stars appeared in a radio broadcast, which was also piped live into theaters. The evening was apparently not a success. Reportedly Talmadge received catcalls in a Detroit theater, and was widely believed to have had someone else give her speech for her, since she was "notoriously speechless at public functions." 39 It was an inauspicious beginning to her abortive talkie career.

Talmadge worked hard with voice coaches to tame her New York accent. As Smith points out, though her voice fell within the acceptable range, her versatility created a problem with any sort of voice, considerably narrowing the range of characters which she could convincingly portray. 40 Her use of her voice was less expert than her use of her face and body, though it is likely that time and experience would have corrected that. Most silent (and stage) veterans improved substantially after their first couple of talkies, as did the directors and technicians as a talking film style emerged. However, as with most of the other big silent stars, the major damage was done by the mere presence of a voice. The sea change that came with talkies swept away stars with perfectly adequate voices. Larger than life personalities needed larger than life voices, and it was only those very few whose voices were so extraordinary that they added to the stars' persona rather than diminished it that made truly successful sound careers. The older stars suffered the most. When a 1931 interviewer said "Norma, who's name means motion pictures to those of us over 20 or 25," he might have added that to those younger she meant ancient history.41

New York Nights (1929) would seem to have been an excellent choice for a talkie debut, since gangster and chorus girl films would be among the most popular genres in the coming decade. The film itself is not bad, and Talmadge gives an respectable performance. Her voice is pleasant, without any noticeable Brooklyn accent. She even sings a few lines. Though the reviews were generally good, the film was disappointing at the box office. 42

|

|

|

Talmadge and William Farnum on the set of the ill-fated Du Barry, Woman of Passion 1930. (Bison Archives / Marc Wanamaker) |

Her last film DuBarry, Woman of Passion (1930), from a turn of the century Belasco play which showed every bit of its age, was a severe miscalculation. It received some good reviews in the regional presses, but the major reviews were bizarre and generally merciless, with Time reporting (quite inaccurately) that she spoke like an elocution teacher, and the New York Times reviewing her wig.43 Talmadge betrays no sign of an accent; only her forced laughter sounds conspicuously artificial. 44 Her big scene of trying to convince her lover that she doesn't care for him is reasonably well played, though her grand Delsartian gesture at the end rather spoils the effect. She does have occasional flashes of her old charm, but for the most part, she is trying altogether too hard. Though her voice is fine, her delivery of the lines is overly dramatic and self-conscious, with too many conspicuous pauses and tonal color changes. She lacks the experience to deliver such moth-eaten lines with the panache and authority necessary to carry them off. Director Sam Taylor added his leaden touch as well. With its slow pace and excessive reaction shots, the film gives the curious impression of a silent with dialog, and must have already looked old-fashioned in late 1930. It's possible also that the overblown sensationalism of the title and the ad campaign may have backfired. 45 It seems as though all involved tried too hard to make a blockbuster film, and ended up instead with a very ponderous and antiquated mess. It was a financial failure, barely grossing $400,000.46

It is said that following a famous telegram from sister Constance, Norma Talmadge retired.47 From contemporary reports, however, it is clear that her decision was not immediate. Just before DuBarry, another project was announced, and as late as 1931 she was telling reporters that she still had two films on her contract with United Artists. 48 Nothing ever came of these projects. Later in the 1930s she appeared briefly in vaudeville and radio with second husband George Jessel, but her 20 year screen career was at an end.

Though Talmadge slowly faded from public view, she was still a fond memory to her fans and was well enough thought of by her colleagues to be named by them in 1955 as one of the top five living silent stars before 1925 in a poll conducted by the George Eastman House. 49

The situation, has been quite different with film historians. Though contemporary critics generally thought highly of her performances (if not necessarily of her films), two high profile film writers did not. In 1925, Iris Barry called her "shockingly inept," and ridiculed her audiences.50 Paul Rotha, who disapproved of virtually everyone in Hollywood, reserved special contempt for Talmadge as a symbol of everything that was wrong with American films. He included her in a list of stars who possessed "manufactured screen personalities," which he describes as "the blank-minded, non-temperamental player, steeped in sex and sheathed in satin, who was admirably suited to movie 'acting', which called for no display of deep emotions, no subtlety, no sensitivity, no delicacy, no guile.51 These opinions have clearly influenced later generations of film writers. Some sources now casually dismiss her as a bad actress, apparently based on this assessment. Ephrahim Katz's Film Encyclopedia states that she "wasn't a particularly good actress." 52 In The United Artists Story, Ronald Bergan speaks of her "limited acting ability," while in his error-riddled account in The Stars, Richard Schickle calls her a "pseudo-actress."53

There may be outside factors which encourage later historians to take Barry's and Rotha's words at face value. The appearance of the 1950 film Singing in the Rain began reports that the character of the Brooklynese silent star Lina Lamont was based on Norma Talmadge. Later film histories began to erroneously state that that Talmadge spoke with a Brooklyn accent in DuBarry, Woman of Passion, a costume film resembling the one being filmed in Singing in the Rain. Even other Hollywood veterans picked up the story and repeated it, as Clarence Brown told Kevin Brownlow: "She was a tragedy of talking pictures. Mme Du Barry with a Brooklyn accent wasn't convincing." 54 The 12th edition of popular reference work Halliwell's Filmgoer's Companion quotes Anita Loos as calling her "A vision of romance as long as she kept her mouth shut. She would have made an ideal Portia until she announced in her Brooklynese, 'The quality of moicy …'" 55 Similar statements are made routinely in film histories and reference works. 56 The comical Lina Lamont became conflated with Norma Talmadge, and now lives on as part of Hollywood lore. Another factor could be called the "Marion Davies syndrome." Talmadge was a minor star at Triangle when she met and married exhibitor Joseph Schenck. The move was highly beneficial to both careers, and he went on to a long and prosperous career as one of the most powerful of Hollywood moguls. In addition, her mother Peg has become a Hollywood legend as one of the most formidable of stage mothers. This has lead some historians to assume that Talmadge was simply a star manufactured by Schenck who "controlled her in alliance with 'Ma' Talmadge, and … used Norma's box-office power to buy himself into United Artists." 57 Even allowing for the fact that historians have not been able to assess her talents firsthand, this overlooks the fact that Talmadge and Schenck rose in the business together, and that her long career, critical success, and vast popularity could hardly have been a case of duping the public.

Even writers who clearly know and love silent film have shown little enthusiasm for her films. The older generation of film historians were boys or young men at the end of the silent era, scarcely the most appreciative audience for the type of women's melodramas in which she specialized. William K. Everson and Edward Wagonknecht are nominally positive on the rare occasions that they mention her, and Wagonknecht is at pains to refute Barry's and Rotha's statements concerning her acting. 58 Yet both admitted in letters to Films in Review that she was not among their favorite stars. 59 James Card could scarcely conceal his indifference at her placing in the Eastman House poll. 60 Later film historians have generally taken little notice of Talmadge, and it has been difficult to do so since until recently most of her films were unavailable. Most of what has been accessible has been her early work, which hardly lives up to her reputation. Of historians who have seen some of films, Kevin Brownlow is the most positive, calling her "a brilliant actress" and "completely natural in the most contrived circumstances." 61 But for most, since she is not a flapper, vamp, nor one of Griffith's child-women, she falls between the cracks of critical inquiry into the period.

|

|

|

[This picture was not in the original article, it replaces a similar picture (same photo session) provided by the editors of Griffithiana. It had the caption "The Woman Disputed, 1928: postcard"] |

Another major handicap to her reassessment has been the nature of her films. Women's melodrama predominates in her oeuvre. These films are often derisively called weepies or soap operas. This is a genre that has been subject to much contempt and derision in most critical circles. For most of this century, anyone with intellectual aspirations was particularly loathe to admit an interest in films whose plot situations centered on romantic or familial problems and featured generous displays of emotion, particularly female emotion. Anita Loos described her chief fans as housewives and gay men, groups whose views have not been valued in critical circles. 62 Though women's films have come under increasing scrutiny by feminist critics, they have not yet turned their attention to the silent era. Most silent film writers are men, who seem to find the genre alien to their interests. Kalton C. Lahue comes clean with his admission: "… never having developed a liking or much of a tolerance for the soap operas in which she found her real fame … I have often found it difficult to sit through some of her films." 63 William J. Mann described her films as "soggy melodramas that only armies of housewives could love." 64 With a reputation like that, few historians have had incentive to troupe to the archives to investigate the films themselves, instead continuing to pass on the same misinformation that Talmadge was an incompetant actress who played in string of identical tearful melodramas.64a

Even though it is far from complete, the fact that most of the body of work by Norma Talmadge has survived and that so much has now been deposited in a single archive has provided the opportunity to reevaluate the career of a major silent screen performer and help to recover her reputation as one of the finest actresses of the silent screen.

I would like to thank the following people for making these films available for viewing: Rosemarry Hanes at the Library of Congress, Charles Silver at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Donna Ross at UCLA Film and Television Archives, Elaina Archer at the Mary Pickford Foundation. A special thanks to Kevin Brownlow for generously sharing his notes, and to Ray de Groat for his editorial and research assistance.

________________________1 Annual Exhibitors Herald Boxoffice poll has Talmadge as the top box office attraction for 1923,1924, and 1925, Richard Dyer MacCann, The Stars Appear, American Movies (Metuchen N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1992), 9. The Photoplay fan poll for 1924 places her sixth, while the Film Daily poll of exhibitors shows her at number five, reprinted in Richard Koszarski, An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915-1928, History of the American Cinema, no. 3 (New York: Scribners, 1990), 262.

2 Koszarski, An Evening's Entertainment, 283.

3 The Raymond Rohauer Collection.

4 Paul Rotha, The Film Till Now, 3rd ed. (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1960), 131

5 Roberta E. Pearson. Eloquent Gestures: The Transformation of Performance Style in the Griffith Biograph Films (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1992), 41-42.

Greg M. Smith, "Silencing the New Woman: Ethnic and Social Mobility in the Melodramas of Norma Talmadge," Journal of Film and Video, 48, no. 3 (Fall 1996): 5.

7 Adela Rogers St. Johns, "Our One and Only Great Actress," Photoplay, February 1926, 58.

8 Bernard Sobel, "How do they do it? The stars' own answers to the question as to what they attribute their personalities and success," Photoplay, March 1921, 40.

9 Gilbert Seldes, An Hour with the Movies and the Talkies, The One Hour Series (Philadelphia: J.B.Lippincott, 1929), 85.

10 Kevin Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968), 145.

11F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tender is the Night (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933), 240.

12 Robert E. Sherwood, The Best Moving Pictures of 1922-23 (Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., 1923) 25.

"Norma was very trying. She showed little interest in her studies. She seemed to be so contented as Mrs. Schenck that she had little ambition for Miss Talmadge . . . she went through her work as though her mind were on the yachting and golfing of recess time." Herbert Howe, "Close-ups & Long Shots" column, Photoplay, June 1924, 58. He then goes on to praise her latest performance in Secrets.

14 For example: "Miss [Fay] Compton's acting in this picture surpasses anything Norma Talmadge has done." Letter in Photoplay, October 1923, 14.

15 Barry Paris. Garbo : A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 80-81.

16 Irene Thiriers, Review of Camille, New York Daily News, 22 April 1927, reprinted in Ron Edelmans, "Camille," in Frank N. Magill, ed., Magills Survey of Cinema: Silent Films. (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Salem Press, c1982), 283.

17 Smith, "Silencing the New Woman, 4.

A typical example: "Norma is Mrs. Joseph Schenck in private life. I know a young thing-a steno-who sometimes breezes into the office in a perfect gale of excitement-'Oh, I just met Norma (or Constance, as the case may be) and she is just the same unaffected girl as when we all went to Flatbush High.'" Anonymous item in "Question & Answers" column, Photoplay, December 1924, 75.

19 Adela Rogers St. Johns, "The Lady of the Vase," Photoplay, August 1923, 104.

20 Sobel, "How do they do it?" 115. "Going … going … near the end of the road, Norma Talmadge looks back" interview in Motion Picture Classic, February, 1931, 38.

21 Anita Loos, The Talmadge Girls: a Memoir (New York: Viking Press, 1978), 52-53. [Editorial note: Randy Bigham has since identfied many uncredited designs by Lucile in Talmadge films]

22 "What their clothes cost, Photoplay, October 1924, 113.

23 Keene Sumner, "Norma Talmadge-a Great Moving Picture Star," American Magazine, June 1922, 37.

24 "Norma is, I believe, generally considered the best-dressed star on screen." Anonymous item in "Questions and Answers" column, Photoplay, June 1920, 127.

25 Alexander Walker, The Shattered Silents (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1979), 2.

26 Versions appeared in Terry Ramsay, "The Romantic History of the Motion Picture, Ch. 19," Photoplay, July 1923, 125, and in greater detail, in Margaret L. Talmadge, The Talmadge Sisters: an Intimate Story of the World's Most Famous Screen Family (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1924), 81-92.

26a [Editorial note: in her scenes in the recently rediscovered fragments of The Battle Cry of Peace, Talmadge gives an excellent performance in a particularly grim film]

27 Julian Johnson, review in Photoplay, August 1917, reprinted in: Anthony Slide, ed., Selected Film Criticism, 1912-1920 (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1982), 203-204.

28 Sherwood, The Best Moving Pictures of 1922-23, 25.

29 It was appreciated by contemporary audiences as well: "While her whole performance was absolutely flawless, special mention must be made of her portrayal of the death of Moonyeen. There was no writhing of limbs, or clinching of hands, or rolling of eyes; just one spasm of pain and then a slow sinking into oblivion. I do not think I have ever seen a death scene more beautifully or naturally played." Hy. C. Binge, letter to Photoplay, January 1923, 16.

30 The reviewer of Photoplay disliked Talmadge's restraint in the part, saying she "seems afraid to act." Review, Photoplay, July 1923, 68.

31 Jeanine Basinger, A Woman's View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930-1960 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 166-170.

32 She also notes that the "noble" stars also tended to be excellent comediennes, though they are never remembered that way. Basinger, A Woman's View, 167-168 ff, 173.

33 Talmadge, The Talmadge Sisters, 208-209.

34 Review, New York Times, 25 February 1924, reprinted in The New York Times Film Reviews, 1913-1931.

35 Talmadge seems interested only in her scenes with Gilbert Roland. By the eighth reel, Talmadge appears to be bored with the whole thing, leaning back and closing her eyes while Beery mugs frantically. He does get her attention briefly when, urging her to cheer up, he pushes up the corners of his mouth a lá Lillian Gish! [Editorial note: Looking back on this, this is one of those instances where I wonder if my eyes or my memory are playing tricks on me. If anyone else watches this print, could you let me know whether or not this really happened?]

|

|

|

[This picture was not in the original article, it replaces a similar picture (same photo session) provided by the editors of Griffithiana. The postard itself merely had the caption "Norma Talmadge"] |

36 Review, Variety, 11 January 1923, reprinted in Variety Film Reviews.

37 Brownlow, The Parades' Gone By, 146.

37a I was a little hard on this film. I later realized that the tape i was viewing was apparently transferred at 16 fps and runs much too slow. In addition, it was missing reels 2-4 which are the funniest parts of the picture. Lacking those reels, the character comes off as something of a stalker. The film was recently restored and plays well with an audience.

38 Sherwood, The Best Moving Pictures of 1922-23, 25.

39 Walker, The Shattered Silents, 3.

40 Smith, "Silencing the New Woman," 9-10.

41 "Going … going … near the end of the road, Norma Talmadge looks back," 38. Variety also noted that her last picture drew better among older audiences and lacked "flaming youth appeal," "Du Barry off in Balto at $15,000," Variety, 15 October 1930, 8.

42 "Leading Film Stars, 1930," Variety, 31 December 1930, 83.

43 Review, Time, Nov. 17, 1930, 53. Mordaunt Hall, Review in New York Times, 3 November 1930, reprinted in New York Times Film Reviews, 1913-1933.

44 For a detailed analysis of her voice, see Smith, "Silencing the New Woman."

45 "The world-famous courtesan is here-A wanton who's lips drugged men's senses… who's beauty ruled a nation!" Advertisement in Variety, 29 October 1930, 18.

46 Scott Eyman, The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution, 1926-1930 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 264.

47 This is quoted in numerous sources in several variants. Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer give it as "Leave them while you're looking good and thank God for the trust funds Mamma set up," The Movies. Rev. ed. (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1970), 246. Anita Loos remembered it a bit more colorfully as "Quit pressing your luck, baby. The critics can't knock those trust funds Mom set up for us." The Talmadge Girls, 2.

48 "Going, Going, Near the End of the Road Norma Talmadge Looks Back," 38-39. "Norma Talmadge's Next," Variety, 8 October 1930, 3.

49 James Card, Seductive Cinema (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 281.

50 Iris Barry, The Spectator (London), 136, no. 5097 (6 March 1926): 415, reprinted in George C. Pratt, Spellbound in Darkness (Greenwich, Conn. : New York Graphic Society, 1966), 415.

51 Rotha, The Film Till Now, 131.

52 Ephraim Katz, The Film Encyclopedia (New York: Putnam Publishing, 1979), s.v. Talmadge, Norma.

53 Ronald Bergan, The United Artists Story (New York: Crown Publisher, 1986), 38. Richard Schickle and Allen Hurlburt, The Stars (New York: Bonanza Books, 1962), 58.

54 Brownlow, The Parade's Gone By, 146.

55 Leslie Halliwell, Halliwell's Filmgoer's Companion, 12th ed., ed. John Walker (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1997), s.v. "Talmadge, Norma." Source of quotation not given. In her The Talmadge Girls, 2, Loos denied that Talmadge had an accent, but said that her voice "lacked nobility."

56 E.g. David Thompson, A Biographical Dictionary of Film (New York: William Morrow, 1976), s.v. "Talmadge, Norma" which states: "Hagen's grinding Bronx accent and the eighteenth-century French setting of the film within Singin' in the Rain have a cruel relevance to the sudden retirement of Norma Talmadge."

57 Thompson, Biographical Dictionary of Film, s.v. "Talmadge, Norma."

58 Edward Wagenknecht, Movies in the Age of Innocence (Norman, Okla. : University of Oklahoma Press, 1962), 177.

59 ". . . Sad to say her style and/or persona just does not hold up well today-though I offer that as a personal opinion, based on having seen only a handful of them and not in the best condition or under the best circumstances." William K. Everson, Letter in Films in Review, December 1976, 637. "Although Norma Talmadge was never one of my favorites . . . I was surprised that more letters came to me relating to her than to any other star." Edward Wagenknecht, Letter in Films in Review, February 1967.

60 Card, Seductive Cinema, 281.

61 Kevin Brownlow, Hollywood: The Pioneers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), 117; The Parade's Gone By, 349.

62 Anita Loos, The Talmadge Girls, 93, 109.

63 Kalton C. Lahue, Ladies in Distress (South Brunswick and New York: A.S. Barnes, 1971), 287.

64 William J. Mann, Wisecracker (New York: Viking, 1998), 56.

64a [Editorial comment: Another prejudice against Talmadge comes from an odd source--fans of Buster Keaton, who was married to Talmadge's sister Natalie. Much has been written about Keaton/Talmadge divorce by Keaton's many biographers, most which tends to demonize the Talmadge family. While I had a sneaking suspicion that this was so at the time I wrote this article, I didn't feel I had enough evidence to mention it. I have since had two people independently bring up the issue in conversation, so apparently I was not alone in making this connection.]

Last revised, September 2, 2007