This project aims to investigate the proposition that what is often called the antiquarian tradition in early modern Europe (roughly 1500-1820), and specifically in its manifestation in Britain and America, was not an intellectual backwater to the mainstream development of experimental science, but was a key component in predisciplinary scholarly production. To do this the project will develop a digitally-enabled multidisciplinary and international research network to explore the antiquarian tradition in local and historical contexts, with a special emphasis on its relationship to the discipline of archaeology.

Objectives and method

- To identify, gather and make digitally available for study approximately 2000 key works in the antiquarian tradition from Britain and the United States.

- To identify, gather and make digitally available for study unpublished source materials (such as letters, images, private and public papers) pertinent to several case studies (of a region, author or period).

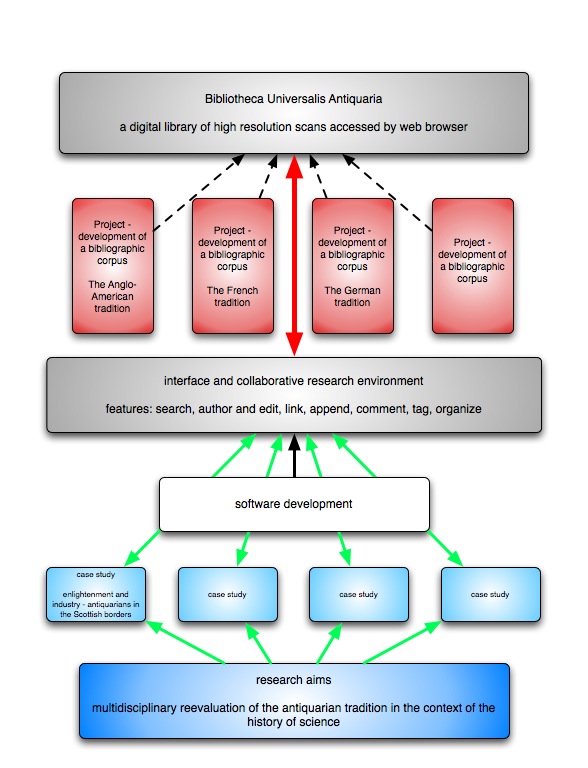

- This collection to be part of a larger digital library of high-resolution digitally scanned source materials: the Bibliotheca Universalis Antiquaria - key works in the global antiquarian tradition, including Asia as well as Europe and the Americas.

- To design and employ a web-based collaborative environment of commentary and critique attached to the digital library to facilitate international and multidisciplinary study of the antiquarian tradition in the context of early scientific practice (fieldwork, collection and sampling, documentation, and archiving).

- To coordinate conventional research seminars and a conference within this network.

- To produce a collaboratively authored book presenting the results of research into specific questions of the relationship of the antiquarian tradition to early modern science, as well as case studies.

Susan Alcock, Professor and Director, Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University;

Giovanna Ceserani, Professor, Department of Classics, Stanford University;

Nicole Coleman, Academic Technology Manager, Stanford Humanities Center;

Harriette Hemmasi, University Librarian, Brown University;

Richard Hingley, Reader, Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, UK;

Henry Lowood, Curator, History of Science and Technology, Stanford Libraries;

Ian Russell, NEH Keough Faculty Fellow, Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies, University of Notre Dame;

Alain Schnapp, Professor, Paris 1, Panthéon-Sorbonne, Founding Director General, Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA) Paris;

Michael Shanks, Professor, Department of Classics, Stanford University;

Christopher Witmore, Research Fellow, Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University.

There were no archaeologists in early modern times. Antiquarian scholars were pastors, lawyers, physicians and teachers, practicing science non-professionally. This came to be called archaeology, but it was not consistently so termed before the mid nineteenth century.

We propose that it is crucial to avoid a teleological view on the history of archaeology and of science. A basic premise of this project is that contemporary archaeology has not developed in a straightforward genealogy from the practices of pre-scientific antiquarians. Nor were those scholars aiming to develop what later came to be called archaeology. We are archaeologists and historians of science researching early modern scholars practicing archaeology, but we are not their scientific descendants. We therefore aim to approach the scholars of the past in their own time, from their own beliefs and philosophies, which also means to explore and to understand their scientific, political, religious and social contexts. This context includes the standard and sometimes questionable narratives of scientific revolution, when scholars discovered new worlds through microscopes and telescopes and via global seafaring. A key question is how the antiquarians became aware of their own modernity and how this awareness prompted a clearer definition of the past, of Graeco-Roman antiquity and of the Christian Middle Ages, but also of pagan prehistory.

We aim to investigate distinct archaeological practices or methods which yielded more or new information and particularly about the past before history, ie prehistory beyond written sources. Prospecting, excavating, collecting, publishing, reading and writing are scientific practices which have produced a variety of written sources for the history of archaeology. We estimate that there are between 1500 and 2000 published works.

Specific research questions include:

- How are archaeological practices before 1820 related to the development of other scientific practices?

- Why were scholars digging and collecting? What were the social, cultural and political circumstances of their scientific practices?

- How they were conducting these practices? How were these practices conceived?

- How far can archaeological practices be conceived as new scientific methods to gain exceptional sources which might be able to assure the scholars of their own modernity?

- How far were archaeological practices before 1800 a matter of religious, regional or national identities?

- Questions of scholarly identity: the figure of the antiquarian. To what extent is the pursuit of archaeological practices a unified phenomenon throughout early modern Britain and America and is the term antiquarian an appropriate one? (The term “Antiquarian” (Latin “Antiquarius”) appears not to have been entirely common throughout early modern Europe for somebody digging up and collecting archaeological finds from the soil).

- The relation of books and media to the work of the antiquarian. For example, how did publication affect the dissemination of local antiquarian knowledge? How important were maps and field drawings? Reading, the quill in hand, for example, has left specific traces in books: marginalia, underlinings or annotations. Such annotated books are rare sources for the individual reception of certain printed key texts for the history of archaeology, which are more valuable if the historic owner of the book is known. We aim to document such marginalia as well as identify and make available other media, published and unpublished.

- The place of scientific instruments in the work of the antiquarian, such as spade and quill, compass and rule. How did such instruments bring about the standardization of antiquarian research?

Antiquarians in the Scottish Borders: between enlightenment and industry. Michael Shanks and Richard Hingley.

Bibliotheca Universalis Antiquaria - the main parent project

Antiquarians - project outline 10-2007 - an application for funding (successful) to Stanford Humanities Center