The len() function returns the length of a string, the number of chars in it. It is valid to have a string of zero characters, written just as '', called the "empty string". The length of the empty string is 0. The len() function in Python is omnipresent - it's used to retrieve the length of every data type, with string just a first example.

The formal name of the string type is "str". The str() function serves to convert many values to a string form. Here is an example this code computes the str form of the number 123:

Going the other direction, the formal name of the integer type is "int", and the int() function takes in a value and tries to convert it to be an int value:

Chars are accessed with zero-based indexing with square brackets, so the first chars is index 0, the next index 1, and the last char is at index len-1.

Accessing a too large index number is an error. Strings are immutable, so they cannot be changed once created. Code to compute a different string always creates a new string in memory to represent the result (e.g. + below), leaving the original strings unchanged.

Concatenate + only works with 2 or more strings, not for example to concatenate a string and an int. Call the function str() function to make a string out of an int, then concatenation works.

String in

The in operator checks, True or False, if something appears anywhere in a string. In this and other string comparisons, characters much match exactly, so 'a' matches 'a', but does not match 'A'.(Mnemonic: this is the same word "in" as used in the for-loop.)

>>> 'c' in 'abcd'

True

>>> 'c' in 'ABCD'

False

>>> 'aa' in 'iiaaii' # test string can be any length

True

>>> 'aaa' in 'iiaaii'

False

>>> '' in 'abcd' # empty string in always True

True

Character Class Tests

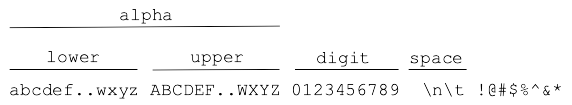

The characters that make up a string can be divided into several categories or "character classes":

alphabetic chars - e.g. 'abcXYZ' that make words. Alphabetic chars are further divided into upper and lowercase versions (the details depend on the particular unicode alphabet).

digit chars - e.g. '0' '1' .. '9' to make numbers

space chars - e.g. space ' ' newline '\n' and tab '\t'

Then there are all the other miscellaneous characters like '$' '^' '<' which are not alphabetic, digit, or space.

These test functions return True if all the chars in s are in the given class:

s.isalpha() - True for alphabetic "word" characters like 'abcXYZ' (applies to "word" characters in other unicode alphabets too like 'Σ')

s.isdigit() - True if all chars in s are digits '0..9'

s.isspace() - True for whitespace char, e.g. space, tab, newline

s.isupper(), s.islower() - True for uppercase / lowercase alphabetic chars. False for other characters like '9' and '$' which do not have upper/lower versions.

>>> 'a'.isalpha()

True

>>> '$'.isalpha()

False

>>> 'a'.islower()

True

>>> 'a'.isupper()

False

>>> s = '\u03A3' # Unicode Sigma char

>>> s

'Σ'

>>> s.isalpha()

True

>>> '6'.isdigit()

True

>>> 'a'.isdigit()

False

>>> '$'.islower()

False

>>> ' '.isspace()

True

>>> '\n'.isspace()

True

Unicode aside: In the roman a-z alphabet, all alphabetic chars have upper/lower versions. In some alphabets, there are chars which are alphabetic, but which do not have upper/lower versions.

Startswith EndsWith

These convenient functions return a boolean True/False depending on what appears at one end of a string. These are convenient when you need to check for something at an end, e.g. if a filename ends with '.html'.

s.startswith(x) - True if s start with string x

s.endswith(x) - True if s ends with string x

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Py')

True

>>> 'Python'.startswith('Px')

False

>>> 'resume.html'.endswith('.html')

True

String find()

s.find(x) - searches s left to right, returns int index where string x appears, or -1 if not found. Use s.find() to compute the index where a substring first appears.

>>> s = 'Python'

>>> s.find('y')

1

>>> s.find('tho')

2

>>> s.find('xx')

-1

There are some more rarely used variations of s.find(): s.find(x, start_index) - which begins the search at the given index instead of at 0; s.rfind(x) does the search right-to-left from the end of the string.

Change Upper/Lower Case

s.lower() - returns a new version of s where each char is converted to its lowercase form, so 'A' becomes 'a'. Chars like '$' are unchanged. The original s is unchanged - a good example of strings being immutable. (See the working with immutable below.) Each unicode alphabet includes its own rules about upper/lower case.

s.upper() - returns an uppercase version of s

>>> s = 'Python123'

>>> s.lower()

'python123'

>>> s.upper()

'PYTHON123'

>>> s

'Python123'

Stripe Whitespace

s.strip() - return a version of s with the whitespace characters from the very start and very end of the string all removed. Handy to clean up strings parsed out of a file.

>>> ' hi there \n'.strip()

'hi there'

String Replace

s.replace(old, new) - returns a version of s where all occurrences of old have been replaced by new. Does not pay attention to word boundaries, just replaces every instance of old in s. Replacing with the empty string effectively deletes the matching strings.

>>> 'this is it'.replace('is', 'xxx')

'thxxx xxx it'

>>> 'this is it'.replace('is', '')

'th it'

Working With Immutable x = change(x)

Strings are "immutable", meaning the chars in a string never change. Instead of changing a string, code creates new strings.

Suppose we have a string, and want to change it to uppercase and add an exclamatin mark at its end, so 'Hello' becomes 'HELLO!'.

The following code looks reasonable but does not work

>>> s = 'Hello'

>>> s.upper() # compute upper, but does not store it

'HELLO'

>>> s # s is not changed

'Hello'

The correct form computes the uppercase form, and also stores it back in the s variable, a sort of x = change(x) form.

>>> s = 'Hello'

>>> s = s.upper() # compute upper, store in s

>>> s = s + '!' # add !, store in s

>>> s # s is the new, computed string

'HELLO!'