Today: revisit variable =, find()/slice practice, text files, standard output, printing, file-reading, crazycat example program

Announce: Nick extra casual hours this fri right after class for non-homework CS questions of any sort, hand back exam end of lecture today

The meaning of a variable "assignment" like var = value

See guide: variables

The single = sets the variable on the left to point to whatever value is computed on the right - "now points at" that value. For example, suppose we have these assignments:

a = 6 b = 7 c = 'Hello' a + b # Value of this expression?

The assignments set up memory like this. Each variable is like a box labeled by the variable's name. The box holds a pointer to the current value.

Using a variable retrieves the value it points to. e.g. a + b here is 13.

Every value in Python has as a formal "type". In memory, every value is tagged with its type, as can be seen above. The type for integer numbers is "int", and the type for strings is "str".

Assigning a new value to a variable, overwrites any previous pointer with a pointer to the new value. This is the "now" part of the rule. The variable points to whatever was assigned most recently.

If a variable is assigned to another variable, e.g. b = a, this sets the one variable to point to the same value as the other. They now point to the same value, which is fine.

a = 10 b = a a + b # Value of this expression?

At this point, the value of a + b is 20.

With that memory picture in mind, we can play with types a little.

Q: What is the difference between 123 and '123'? How do they work with the + operator?

>>> a = 123 >>> b = 5 >>> a + b 128 >>> >>> a = 'hi' >>> b = 'there' >>> a + b 'hithere' >>> >>> # e.g. line is out of a file - a string >>> # convert str form to int >>> line = '123\n' >>> int(line) 123 >>> >>> # works the other way too >>> str(123) '123'

Int indexing into something is extremely common in computer code. So of course doing it slightly wrong is very common as well. So common, there is a phrase for it - "off by one error" or OBO — it even has its own wikipedia page. You can feel some kinship with other programmers each time you stumble on one of these.

"This code is perfect! Why is this not working. Why is this not work ... oh, off by one error. We meet again!"

'aabb' -> 'bbbbaaaa'

We'll say the midpoint of a string is index len // 2, dividing the string into a left half before the midpoint and a right half starting at the midpoint. Given string s, return a new string made of 2 copies of right followed by 2 copies of left. So 'aabb' returns 'bbbbaaaa'.

Solution

def right_left(s):

mid = len(s) // 2

left = s[:mid]

right = s[mid:]

return right + right + left + left

# Style comparison:

# Without using any variables, the solution

# is longer and not so readable:

# return s[len(s) // 2:] + s[len(s) // 2:] + s[:len(s) // 2] + s[:len(s) // 2]

Notice the decomp-by-var strategy: break the computation into smaller, named parts. A big improvement.

Here is what it looks like without the variables. Not so easy on the eyes!

s[len(s) // 2:] + s[len(s) // 2:] + s[:len(s) // 2] + s[:len(s) // 2]

This looks simple, but the details are tricky. Make a drawing.

Given string s. Find the first '@' within s. Return the len-3 substring immediately following the '@'. Except, if there is no '@' or there are not 3 chars after the @, return ''.

Suggestion: what is the index of the last char we want to pull out? Is that index beyond the valid chars in s, then the string is not long enough and we return the empty string.

Solution

def at_3(s):

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

# Is at + 3 past end of string?

# Could "or" combine with above

if at + 3 >= len(s):

return ''

return s[at + 1:at + 4]

# Working out >= above ... drawing!

> parens()

'xxx(abc)xxx' -> 'abc'

This is nice, realistic string problem with a little logic in it.

s.find() variant with 2 params: s.find(target, start_index) - start search at start_index vs. starting search at index 0. Returns -1 if not found, as usual.

Given string s.

Look for a '(.....)' within s -

look for the first '(' in s, then the

first ')' after the '(', using the second start_index

parameter of .find(). If both parens are found,

return the chars between them, so

'xxx(abc)xxx' returns 'abc'. If

no such pair of parens is found, return the

empty string. Think about the input

'))(abc)'

Thinking about this input: '))(abc)'. Starting hint code, something like this, to find the right paren after the left paren:

left = s.find('(')

...

right = s.find(')', left + 1)

Solution

def parens(s):

left = s.find('(')

if left == -1:

return ''

# Start search at left + 1:

right = s.find(')', left + 1)

if right == -1:

return ''

# Use slice to pull out chars between left/right

return s[left + 1:right]

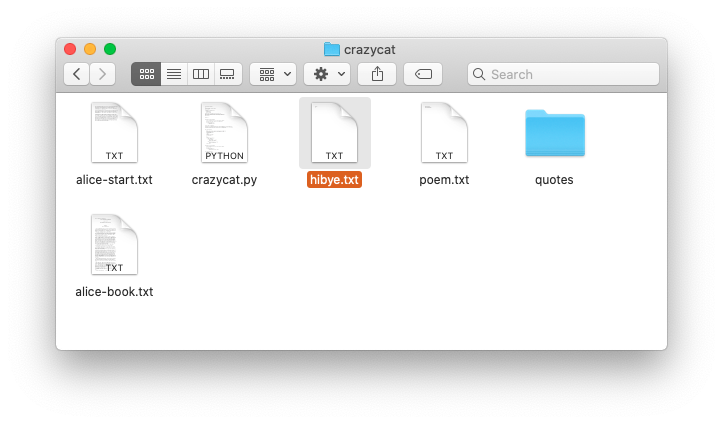

We'll use the crazycat example to demonstrate files, file-processing, printing, standard output.

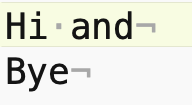

The file named "hibye.txt" is in the crazycat folder. A "file" has a name and stores a series of bytes on the computer. More details later.

The hibye.txt file has 2 lines, each line has a '\n' at the end.

The first line has a space, aka ' ', between the two words. Here is the complete contents:

Hi and bye

Here is what that file looks like in an editor that shows little

gray marks for the space and \n:

In Fact the contents of that file can be expressed as a Python string:

'Hi and\nbye\n'

How many chars are in that file (each \n is one char)? There are 11 chars. Roman alphabet A-Z chars like this take up 1 byte per char. Characters in other languages take 2 or 4 bytes per char. Use your operating system to get the information about the hibye.txt file. What size in bytes does your operating system report for this file?

So when you send a 50 char text message .. that's about 50 bytes sent on the network + some overhead. Text uses very few bytes compared to sound or images or video.

Use backslash \ to include special chars within a string literal. Note: different from the regular slash / on the same key as ?.

s = 'isn\'t' # or use double quotes # s = "isn't" \n newline char \\ backlash char \' single quote \" double quote

In the old days, there were two chars to end a line. The \r "carriage return", would move the typing head back to the left edge. The \n "new line" would advance to the next line. So in old systems, e.g. DOS, the end of a line is marked by two chars next to each other \r\n. On Windows, you will see text files with this convention to this this day. Python code largely insulates your code from this detail - the for line in f form shown below will go through the lines, regardless of what line-ending they are encoded with.

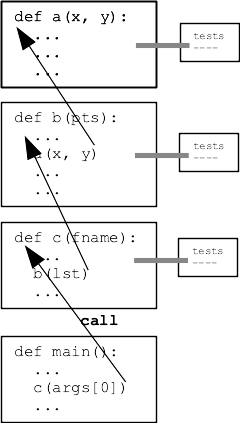

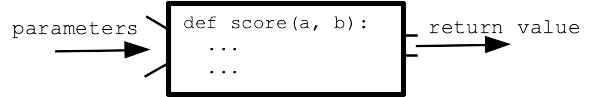

Q: How does data flow between the functions in your program?

A: Parameters and Return value

Parameters carry data from the caller code into a function when it is called. The return value of a function carries data back to the caller.

This is the key data flow in your program. It is 100% the basis of the Doctests. It is also the basis of the old black-box picture of a function

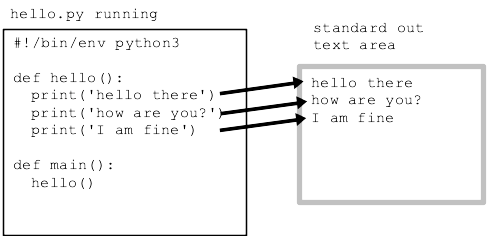

BUT .. there is an additional, parallel output area for a program, shared by all its functions.

There is a Standard Output area associated with every run of a program. It is a text area made of lines of text. A function can append a line of text to standard out, and conveniently that text will appear in the terminal window hosting that run of python code. Standard out is associated with the print() function below.

See guide: print()

>>> print('hello', 'there', '!')

hello there !

>>> print('hello', 123, '!')

hello 123 !

>>> print(1, 2, 3)

1 2 3

>>> print('hello', 123, '!', sep=':') # sep= between items

hello:123:!

>>> print(1, 2, 3, end='xxx\n') # end= what goes at end

1 2 3xxx

>>> print(1, 2, 3, end='') # suppress the \n

1 2 3>>>

Return and print() are both ways to get data out of a function, so they can be confused with each other. We will be careful when specifying a function to say that it should "return" a value (very common), or it should "print" something to standard output (rare). Return is the most common way to communicate data out of a function, but below are some print examples.

This example program is complete, showing some functions, Doctests, and file-reading.

See guide: command line

Open a terminal in the crazycat directory (see the Command Line guide for more information running in the terminal). Terminal commands - work in both Mac and Windows. When you type command in the terminal, you are typing command directly to the operating system that runs your computer - Mac OS, or Windows, or Linux.

pwd - print out what directory we are in

ls - see list of filenames ("dir" on older Windows)

cat filename - see file contents ("type" on older Windows)

$ ls alice-book.txt crazycat.py poem.txt alice-start.txt hibye.txt quotes $ cat poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme $

$ python3 crazycat.py poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme $ python3 crazycat.py hibye.txt Hi and bye $

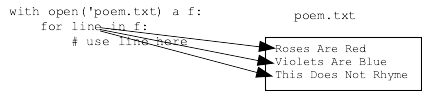

Here is the canonical file-reading code:

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

# use line in here

Visualization of how the variable "line" behaves for each iteration of the loop:

Here is the complete code for the "cat" feature - printing out the contents of a file. Why do we need end='' here? The line already has \n at its end, so we get double spacing if print() adds its standard \n.

def print_file_plain(filename):

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

# use line in here

print(line, end='')

The main() function looks for '-crazy' option on the command line. We'll learn how to code that up soon. For now, just know that main() calls the print_file_crazy() function which calls the crazy_line() helper.

Here is command line to run with -crazy option

$ python3 crazycat.py -crazy poem.txt rOSES aRE rED vIOLETS aRE bLUE tHIS dOES nOT rHYME

def crazy_line(line):

"""

Given a line of text, returns a "crazy" version of that line,

where upper/lower case have all been swapped, so 'Hello'

returns 'hELLO'.

>>> crazy_line('Hello')

'hELLO'

>>> crazy_line('@xYz!')

'@XyZ!'

>>> crazy_line('')

''

"""

result = ''

for i in range(len(line)):

char = line[i]

if char.islower():

result += char.upper()

else:

result += char.lower()

return result

Important technique: see how how the line string is passed into the crazy_line() helper. The result of the helper is sent to print(). Very compact, really using parameter/result data flow here.

Key Line: print(crazy_line(line), end='')

The code is similar to print_file_plain() but passes each line through the crazy_line() function before printing.

def print_file_crazy(filename):

"""

Given a filename, read all its lines and print them out

in crazy form.

"""

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

print(crazy_line(line), end='')

Try running the code with alice-start.txt is the first few paragraphs of Alice in Wonderland, and alice-book is the entire text of the book. Try the entire text.

1. Note how fast it is. Your computer is operating at, say, 2Ghz, 2 billion operations per second. Even if each Python line of code takes, say, 10 operations, that's still a speed that is hard for the mind to grasp.

2. Try running this way, works on all operating systems:

$ python3 crazycat.py -crazy alice-start.txt > capture.txt

What does this do? Instead of printing to the terminal, it captures standard output to a file "capture.txt". Use "ls" and "cat" to look at the new file. This is a super handy way to use your programs. You run the program, experimenting and seeing the output directly. When you have a form you, like use > once to capture the output.