Today: a few loose ends, boolean precedence, mind-blowing drawing. No class monday!

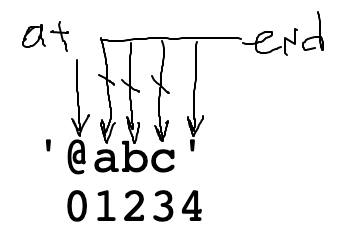

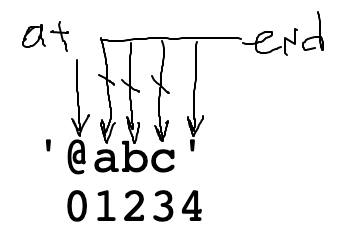

Recall the at_words() parsing function. The most difficult part is the "end" loop to locate where the word ends. We'll look at that again here. Below is v1 of the code and a picture of the data to work out what it's going to do.

# code v1 - almost

# move "end" past alpha chars

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

Problem: index 4 is not a valid index into s. If the code ever runs s[4].isalpha(), it will crash.

'@abc' 01234

end < len(s) GuardCannot access s[end] when end is too big. Add a < guard to its left. This stops the loop when end gets to 4. This code is correct.

# code v2 - correct

# move "end" past alpha chars

# len(s) == 4

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while end < len(s) and s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

The "and" evaluates left to right. As soon as it sees a False it stops. In this way the < len(s) guard checks that "end" is a valid number, before s[end] tries to use it. This a standard pattern: the index-is-valid guard is first, then "and", then s[end] that uses the index. We'll do another example with this later in this lecture.

See the guide for details Boolean Expression

The code below looks reasonable, but doesn't quite work right

def good_day(age, weekend, raining):

if not raining and age < 30 or weekend:

print('good day')

Because and is higher precedence than or as written above, the code above acts like the following (the and going before the or):

if (not raining and age < 30) or weekend:

What is a set of data that this code will evaluate incorrectly? raining=True, age=anything, weekend=True .. the or weekend makes the whole thing True, no matter what the other values are. This does not match the good-day definition above, which requires that it not be raining.

The solution we will spell out is not difficult.

Solution

def good_day(age, weekend, raining):

if not raining and (age < 30 or weekend):

print('good day')

Go back to the "parse1" section on the experimental server. See the at_words99() problem towards the end of the section. This problem is interesting as it is now operating with the power of our reference problem - be able to parse all the hash-tags out of a tweet.

at_words99(): For each '@' in s, parse out the "word" substring of 1 or more alphabetic or digit chars which immediately follow the '@', so '@abc @ @1x2y @1' returns ['abc', '1x2y', '1']. This is at_words() with the "or" complication added.

Like before, but now a word is made of alpha or digit - a needed change for this to work in the real world for our hashtags goal. This is probably our most complicated line of code thus far in the quarter! Fortunately, it's a re-usable pattern for any of these "find end of xxxx" problems.

The most difficult part is the "end" loop to locate where the word ends. What is the while test here? (Bring up at_words99() in other window to work it out). We want to use "or" to allow alpha or digit.

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while ??????????:

end += 1

'@a12' 01234

# 1. Still have the < guard

# 2. Use "or" to allow isalpha() or isdigit()

# 3. Need to add parens, since this has and+or combination

while end < len(s) and (s[end].isalpha() or s[end].isdigit()):

end += 1

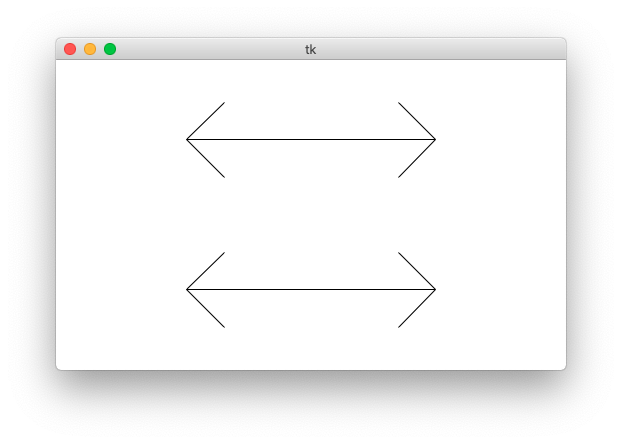

Download the flex-arrow.zip to work this fun little drawing example.

x = 0 y = 0 width = 200 x2 = x + width # this is fine canvas.draw_line(x, y, x2, y) # this is fine too # draw a line 2/3 as long # note that x3 is not an int x3 = x + width * 0.66 canvas.draw_line(x, y, x3, y)

The "flex" parameter is 0..1.0: the fraction of the arrow's length used for the arrow heads. The arms of the arrow will go at a 45-degree angle away from the horizontal.

Specify flex on the command line so you can see how it works. Close the window to exit the program. You can also specify larger canvas sizes.

$ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.25 $ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.15 $ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.1 1200 600

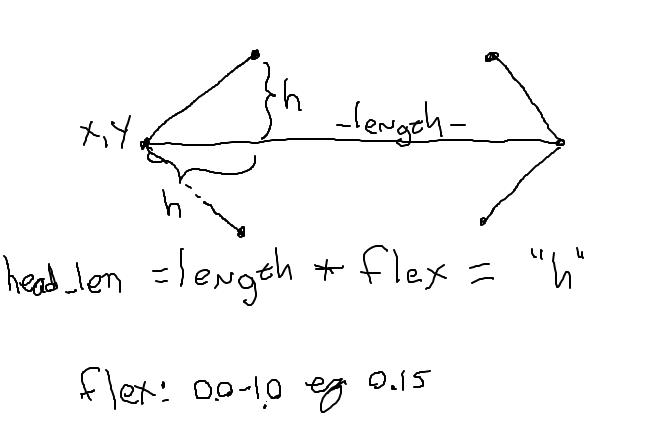

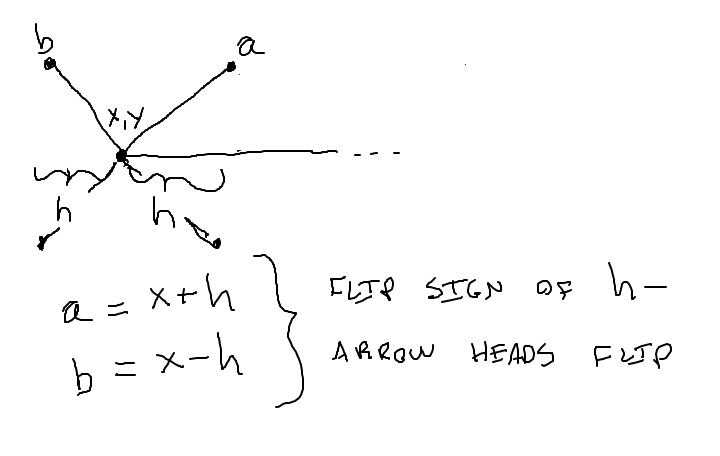

Look at the draw_arrow() function. It is given x,y of the left endpoint of the arrow and the horizontal length of the arrow in pixels. The "flex" number is between 0 .. 1.0, giving the head_len - the horizontal extent of the arrow head - called "h" in the diagram. Main() calls draw_arrow() twice, drawing two arrows in the window.

The code here draws the left arrow head.

def draw_arrow(canvas, x, y, length, flex):

"""

Draw a horizontal line with arrow heads at both ends.

It's left endpoint at x,y, extending for length pixels.

"flex" is 0.0 .. 1.0, the fraction of length that the arrow

heads should extend horizontally.

"""

# Compute where the line ends, draw it

x_right = x + length - 1

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x_right, y)

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines, up and down from left endpoint

head_len = flex * length

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x + head_len, y - head_len) # up

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x + head_len, y + head_len) # down

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines from the right endpoint

# your code here

pass

Add the code to draw the head on the right endpoint of the arrow. Look at the planning diagram blelow, the head_len variable "h" in the drawing. This is a solid, CS106A applied-math exercise.

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines from the right endpoint

# your code here

pass

canvas.draw_line(x_right, y, x_right - head_len, y - head_len) # up

canvas.draw_line(x_right, y, x_right - head_len, y + head_len) # down

Now we're going to show you something a little beyond the regular CS106A level, and it's a teeny bit mind warping.

Run the code with -trick like this, see what you get.

$ python3 flex-arrow.py -trick 0.1 1200 600

Maybe we'll get this far

No!

Each test is like drilling for oil. We drill five holes, and find no oil in all of them. Does that mean there is no oil? Probably there is no oil, but we can't say for sure. Each test is looking for a bug. As a practical matter, even just a few tests do a great job finding bugs. You do not need a zillion tests, and probably your functions in CS106A bear this out - when you have 4 tests .. that's often plenty.

In other words, just a few tests provide great value. Doctests are a great "deal" in this sense. But they do not prove the code is 100% correct.