Today: if statement, ==, function call, decomposition

While loop is power. If-statement is control, controlling if lines are run or not

We'll run this simple bit of code first, so you can see what it does. Then we'll look at the bits of code that go into it.

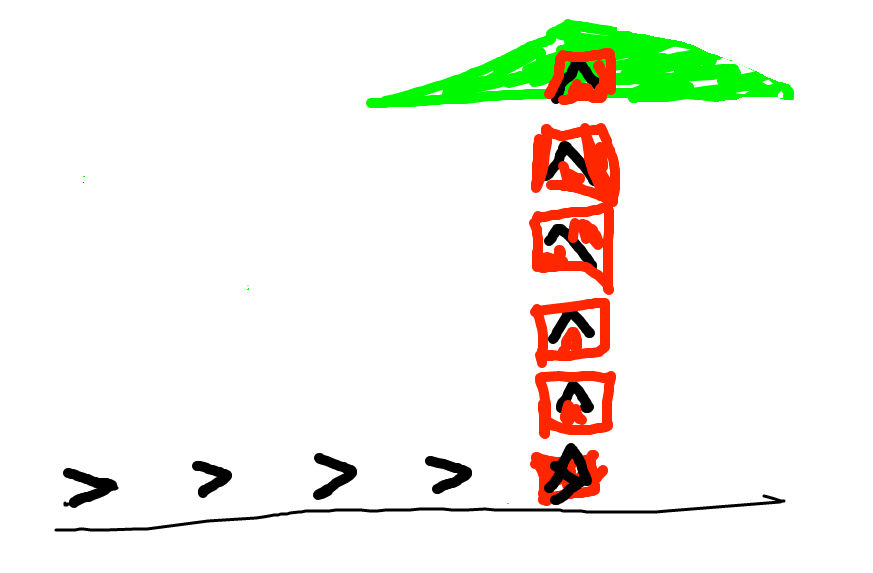

Problem statement: Move bit forward until blocked. For each moved-to square, if the square is blue, change it to green. (Demo: this code is complete.).

For reference here is the code:

def change_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

Syntax 4 parts (similar to "while"): if, boolean test-expression, colon, indented body lines

if test-expression:

body lines

Here are the key lines of code:

....

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

....

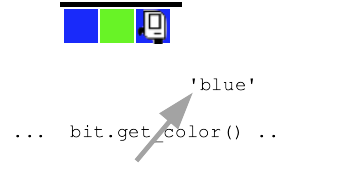

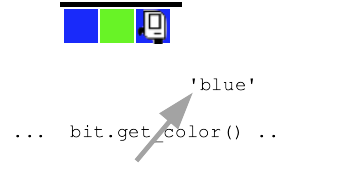

Suppose bit is on a squared painted 'blue', as shown below. Here is diagram - visualizing that bit.get_color() is called and it's like there's an arrow coming out of it with the returned 'blue' to be used by the calling code.

== Compares Two Values - BooleanLook at the if-statement. What is the translation of that into English? ..

For each moved-to square. If the square is blue, paint it green.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

== !=

if bit.get_color() == 'red':

# run this if color is 'red'

if bit.get_color() == None:

# run this if square is not painted

if bit.get_color() != 'red':

# run this if square is anything but 'red'

# e.g. 'green' 'blue' or None

A medium hard problem to look at the thinking and coding process

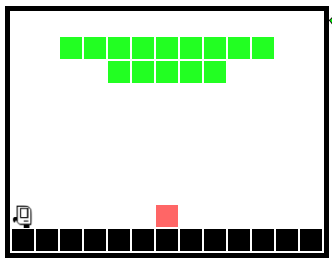

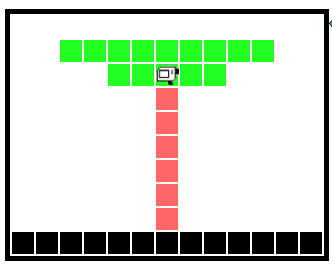

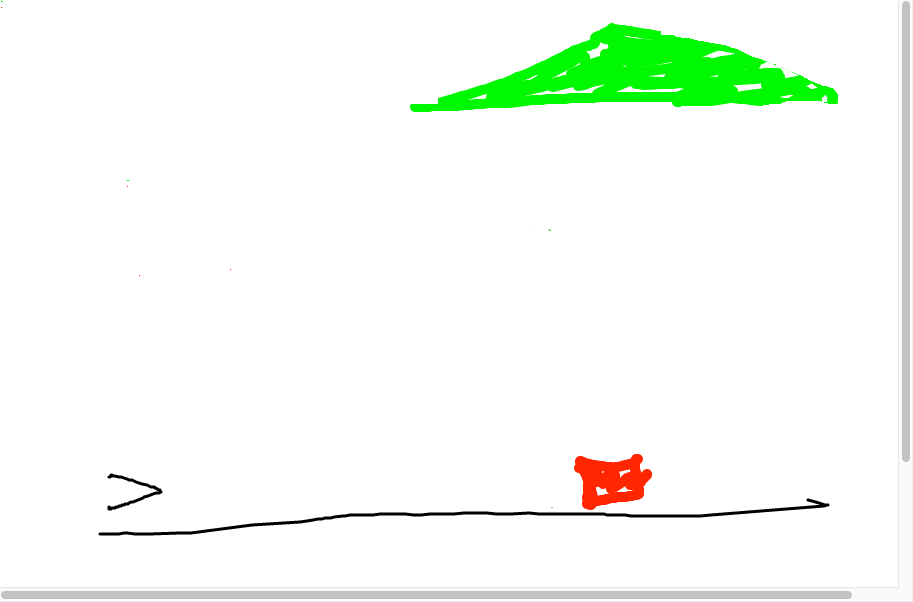

> Fix Tree

Before:

After:

We have art for these. No expense has been spared!

Don't do it just in your head - too much detail. Need to be able to work gradually and carefully.

Draw a typical "before" state.

Look at the before state - what code can advance this?

You have the current state. What code could advance things to the next goal?

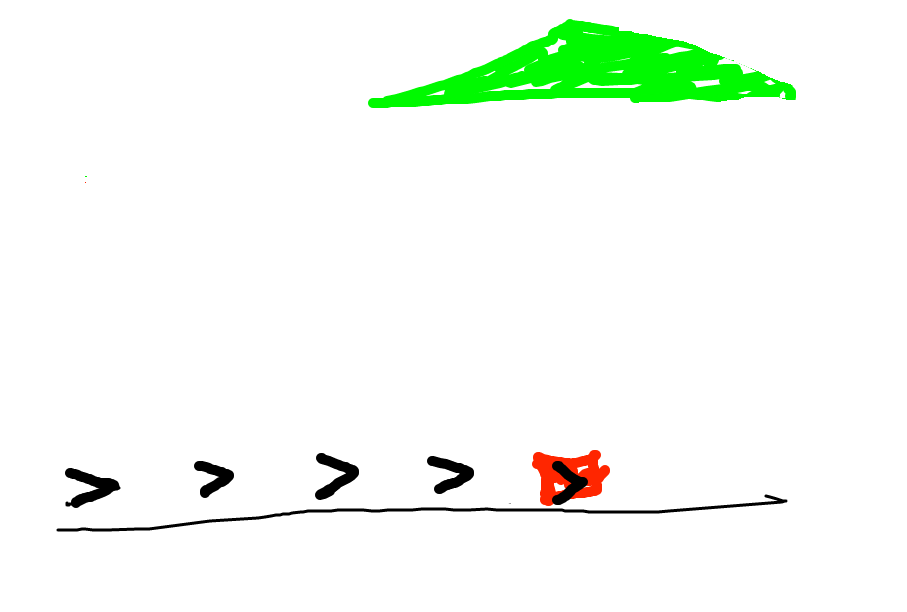

Q: Look at those bit positions. When do you want bit to move, and when not to move?

A: Want bit to move when the square is not red. What is the code for that?

Aside: if you were talking to a human, you would just say "make it look like this" and point to the goal. But not with a computer! You need to spell out the concrete steps to make the goal for the computer.

In this, case we're thinking while-loop. Draw in the various spots

bit will be in. What is a square where we do not want bit to move?

When bit is on the red square. Otherwise bit should move. What does that look

like in code?

Code looks like...

while bit.get_color() != 'red':

bit.move()

Ok, run it and see. Sometimes it will not do what we thought.

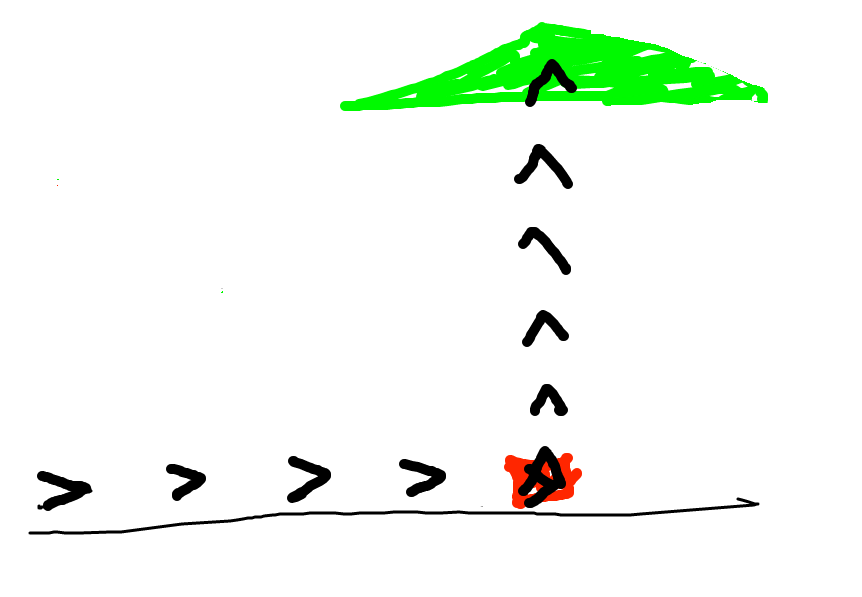

Ok what is the next goal? What would be code to advance to that?

I think a reasonable guess here is similar to the first loop, but painting red, like this

while bit.get_color() != 'green':

bit.move()

bit.paint('red')

OOPS, that code looks reasonable, but does not do what we wanted. The question is: what sequence of actions did the code take to get this output? That's a better question than "why doesn't this work".

Go back to our drawing. Think about the paint/red and the while loop, how they interact.

The problem is that we paint the square red, and then go back to the loop test that is looking for green, which we just obliterated with red. One solution: add an if-statement, only paint blank squares red, otherwise leave the square alone.

That gives us this solution, which works perfectly..

def fix_tree(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.get_color() != 'red':

bit.move()

bit.left()

while bit.get_color() != 'green':

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == None:

bit.paint('red')

Use a drawing to think through the details of what the code is doing. It's tempting to just stare at the code and hit the Run button a lot! That doesn't work! Why is the code doing that?

Or put another way, in office hours, a very common question from the TA would be: can you make a little drawing of the input here, and then look at your line 6, and think about what it's going to do. All the TA does is prompt you to make a drawing and then use that to think about your code.

In the Wizard of EarthSea novels by Ursula Le Guin .. each thing in the world has its secret, true name. A magician calls a thing's true name, invoking that thing's power. Function calls work like this - a function has a name, you call a function by its name, invoking its power.

We've seen def many times - defines a function. Note that

each function has a name and body lines of code, like this "go_west" function:

def go_west(bit):

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

...

To "call" a function means to go run its code, and there are two common ways it is done in Python. One way to call a function in Python is the "object oriented" form, aka noun.verb. The bit functions use this method, e.g. bit.left(), where "left" is the name of the function.

The other way to call a function, which we will use here, is simply writing its name with parenthesis after it. For the above function named "go_west", code to call it looks like:

...

go_west(bit)

...

Both of these function-call styles are widely used in Python code.

Say the program is running through some lines, which we'll call the "caller" lines. Then the run gets to the following function call line; what happens?

# caller lines

bit.right()

go_west(bit) # what does this do?

bit.left()

...

What the go_west(bit) directs the computer to do: (a) go run the lines inside the "go_west" function, suspend running here in the caller. (b) When go_west() is done, return to this exact spot in the caller lines and continue running with the next line. In other words, the program runs one function at a time, and function-call jumps over to run that function.

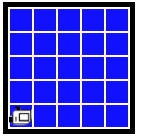

This example demonstrates bit code combined with divide-and-conquer decomposition.

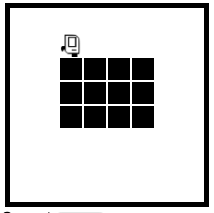

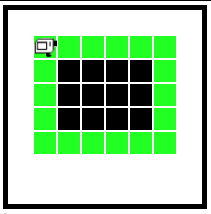

The whole program does this: bit starts at the upper left facing down. We want to fill the whole world with blue, like this

Program Before:

Program After:

First we'll decompose out a fill_row_blue() function that just does 1 row.

This is a "helper" function - solves a smaller sub-problem.

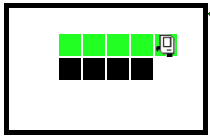

fill_row_blue() Before (pre)

fill_row_blue After (post):

You could write the code for this one, but we're providing it today to get to the next part.

Run the fill_row_blue a few times, see what it does.

def fill_row_blue(bit):

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right()

bit.right()

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.left()

-Now comes the key, magic step for today. First, know what fill_row_blue() does exactly, pre/post.

bit.left_clear() + not

if bit.left_clear():

# run here if left is clear

if not bit.left_clear():

# run here if left is blocked, aka not-clear

Bit starts next to a block of solid squares (these are not "clear" for moving). Bit goes around the 4 sides clockwise, painting everything green.

Cover Before (pre):

cover_row() After (post):

cover_square() After (post):

cover_side(bit): Move bit forward until the right side is clear. Color every square green. (demonstrates not left-clear test).

Run this code with case-1, see what it does. Study the code to see how it works, think about its pre/post (make a little drawing).

cover_square(bit): Bit begins atop the upper left corner, facing right. Paint all 4 sides green. End to the left of the original position, facing up.

Start by calling cover_side() once. How can we solve the whole thing? How to address the pre/post conditions of cover_side()? Key ideas: