Today: many basic examples, observations about loops, top-down decomposition

Solving Bit problems relies on a few code patterns - the while+front_clear, if+get_color(), and so on. In lecture we've had to demonstrate these, maybe once each, but that's not quite enough for students to feel solid with each pattern. Therefore, below are eight Bit problems with solutions available, that are living demonstrations of every pattern of Bit code we are going to do.

Fri Special One-time Office Hours - Nick office hours today at 4:00pm .. to solve and discuss any of these examples, good preamble for hw1

> all-blue (while + front_clear)

> change-blue (while + if/get_color)

> bit-rgb (while + first/last square)

> double-move (while + two moves in loop)

> fix-tree (while-until-color, our make-a-drawing example)

> reverse-coyote (while + right_clear)

> standard-coyote (while + left_clear + not)

> climb (multiple whiles)

> reverse-santa (multiple whiles)

> standard-santa (multiple whiles) added

> falling-water (multiple whiles, even/odd issue) added

def all_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename) # provided

bit.paint('blue')

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

When a problem says "until blocked", you typically use front_clear() a the test. In the loop, the code moves forward one square, paints it blue.

Since the loop does move-then-paint, it can't do the first square. We add a separate paint to do the first square. The while loop is not set up to do the first square, so we accept for many problems that we will need to add extra code before the loop if any action is needed for the first square.

Notice that the test of the while is essentially the "go" condition - when that test is true, Bit should move forward. Conversely, when the test is False, don't move. Keep the phrase "test = go" in mind, handy when thinking of code for a new problem.

Q: Look at the code. When line 6 runs, what line runs next?

A: it's not line 7! It's line 4, the while-test. The loop always runs the test after the last loop line. Only when test is False, then line 7 gets to run.

Look at Case-4, a world which is 1 square wide. Use the slider to go the start of this one, and step through the lines to see how the while-test behaves. In this case, the while-test is False the very first time! The result is, the body lines run zero times. This is fine actually. There were zero squares to move to, so looping zero times is perfect. This is an example of an "edge" case, the smallest possible input. It's nice that the while loop handles this edge case without any extra code.

Change the all_blue code to this

...

while bit.get_color() != 'red': # BUG

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

The role of the while-test is to stop bit once it reaches the wall (i.e. front is not clear).

With this buggy code, the test is never False, so the loop never exits. Bit reaches the right side, but keeps trying to move(). Moving into a wall or black square (i.e. not a clear square) is an error, resulting in an error message like this:

Exception: Bad move, front is not clear, in:all_blue line 5 (Case 1)

If you see an exception like that, your code is doing a move() when the front is not clear, which is an error. You need to look at your logic, only doing a move() when the square in front is known to be clear.

Here is a buggy All Blue - instead of move() have bit do right() and the left() - a sort of "waggle dance" like bees do in the hive. Notice that .. bit never moves forward. Bit can do this for eternity, and never leave that first square! Everyone has days like that.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.right() # waggle dance!

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

Run the code - you will see a message about a timeout, suggesting that this code does not seem to reach an end.

move vs. move()Python syntax requires the parenthesis () to make a function call. Unfortunately, if you omit them, easy enough to do, it does not make a function call. So the code below looks right, but actually it's an infinite loop. Bit never moves. Try it yourself and see, then fix it.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move

bit.paint('blue')

> double-move (while + two moves in loop)

The code below is a good first try, but it generates a move error. Why? The first move is safe, but the second is not. Add an if-statement, so the second move is only done when it is legal.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.move()

bit.paint('red')

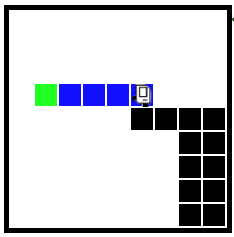

> reverse-coyote (while + right_clear)

Based on the RoadRunner cartoons, which have a real lightness to them. In the cartoons, the coyote is always running off the side of the cliff and hanging in space for a moment. For this problem, the coyote tries to run back onto the cliff before falling.

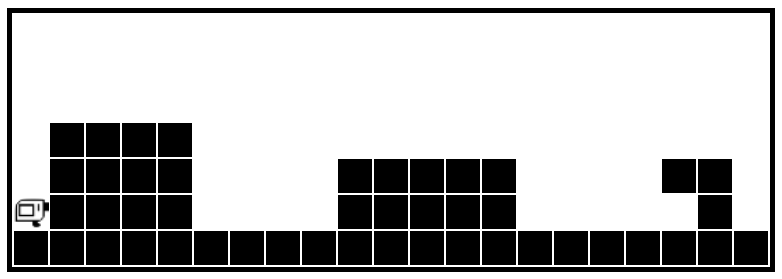

Before:

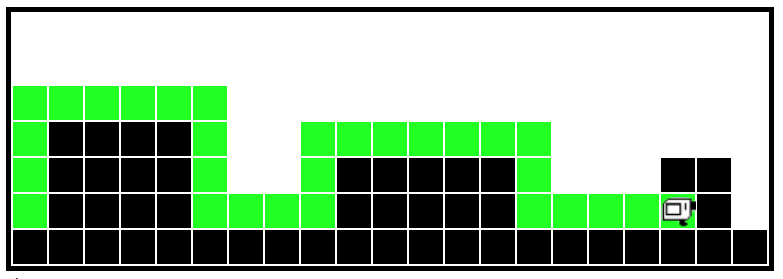

After:

Q: What is the while test for this? Remember that Test = Go. What is the test that is True when we want to move, and False when do not want to move?

A: bit.right_clear()

We run through lecture examples for the important ideas, but it's pretty fast. It's hard to know in the moment if you've gotten the idea or not. Later you'll see a homework problem on the same topic. If you are stuck, a good use of time is to go back to the lecture notes, and see if you can work the lecture problem yourself, peeking at the solution here and there as you go. Ultimately, you want to be able to write the solution without peeking at a similar problem, but to learn the material it's fine.

CS106A doe not just teach coding. It has always taught how to write clean code with good style. Your section leader will talk with you about the correctness of code, but also pointers for good style.

All the code we show you will follow PEP8, so just picking up the style tactic that way is the easiest.

Python Guide - click on the Style section, we'll pick out a few things today (for hw1), re-visit it for the rest later.

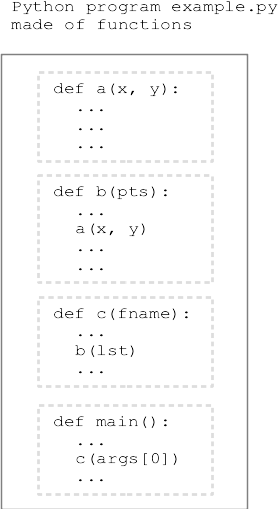

Our big picture - program made up of functions

> Hurdles

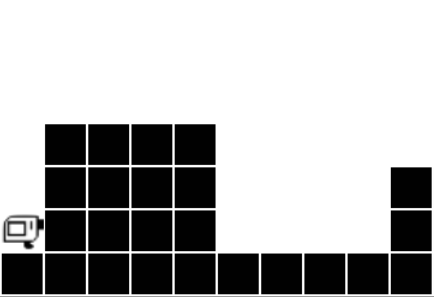

Before

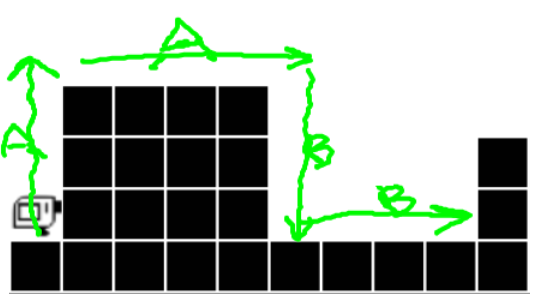

After

while not bit.right_clear():

bit.move()

def solve_hurdles(filename):

"""

Solve the sequence of hurdles.

Start facing north at the first hurdle.

Finish facing north at the end.

(provided)

"""

while bit.front_clear():

solve_1_hurdle(bit)

Helper function - solve one hurdle. If we had this, solve_hurdles would be easy. Just doing one hurdle is not so intimidating. Divide and conquer!

What helper functions would be useful here? Make observation about the 4 moves that make up a hurdle.

Here is a sketch, working out that there are two sub-problem types

Here is the solve_1_hurdle() code - sketching that we have go_wall_right() and go_until_blocked() helpers. Can write this before we write the helpers. Think about pre/post for each.

def solve_1_hurdle(bit):

"""

Solve one hurdle, painting all squares green.

Start facing up at the hurdle's left edge.

End facing up at the start of the next hurdle.

"""

go_wall_right(bit)

bit.right()

bit.move()

go_wall_right(bit)

bit.right()

go_until_blocked(bit)

bit.left()

go_until_blocked(bit)

bit.left()

Now write two more helpers. Here we see the importance of the pre/post to mesh the functions together.

def go_wall_right(bit):

"""

Move bit forward so long as there

is a wall to the right. Paint

all squares green. Leave bit with the

original facing.

"""

bit.paint('green')

while not bit.right_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

def go_until_blocked(bit):

"""

Move bit forward until blocked.

Painting all squares green.

Leave bit with the original facing.

"""

bit.paint('green')

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

When all the helpers are built, we can try running it on a few worlds. Switch to a small font so you can see all the code at once, watch the run jump around. Go, Bit go!

Some other points to clean up, if we have time.

There is a convention to put the smallest, helper functions first in a file. The larger functions that call them down below. This is just a habit; Python code will work with the functions in any order. Placing the helpers first does have a kind of logic — looking at solve_1_hurdle(), the functions it uses are defined above it, not after.

At the top of each function is a description of what the function does within triple-quote marks - we'll start writing these from now on. This is a Python convention known as "Pydoc" for each function. The description is just a summary of the pre/post in words.

Previously we had separate testing for each helper which is ideal, and we will do that again in CS106A. In this case, we just run the whole thing and see if it works without the benefit of helper tests.