Today: int vs. float, modules, how the internet works (sep page)

Two Math Systems, "int" and "float" (Recall)

- Two Systems

- int and float are two different worlds

- "float" .. floating decimal point, moves around

- Float and int - each have their own area on the chip

- Look similar, but distinct

6 - the int six

6.0 - the float six

'6' - the string of int 6

# int

3 100 -2

# float, has a "."

3.14 -26.2 6.022e23

Math Works

- Math works: + - * / min() max() for both int and float fine:

- i.e. mostly don't have to think about it

- Need to use int for indexing - [ ], grid.get(x, y)

- Foreshadow:

Float mostly works easily

BUT Float has one crazy flaw .. revealed below

- Clickbait: I clicked on the float lecture, and you will not believe what happened!

Mixed Case: int + float = float "promotion"

- Mixed case: int + float

- Combine int and float .. yields float

- Any float value "promotes" the computation to float

- Note how output below is all float, some int inputs

>>> 1 + 1 + 1

3

>>> 1 + 1 + 1.0 # float promotion

3.0

>>> 3.14 * 2

6.28

>>> 3.0 * 3

9.0

>>> 3.14 * 2 + 1

7.28

float() int() Conversions

-Use float() to convert str to float value, similar to int()

>>> int(3.14) # float -> int, truncation

3

>>> float(3) # int -> float

3.0

>>> int('16') # str -> int

16

>>> float('3.14') # str -> float

3.14

>>> int('3.14')

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '3.14'

Float - One Crazy Flaw - 1/10

- Note: do not panic! We can work with this. But it is shocking.

- Float arithmetic is a little imprecise

- Off at the 15th digit .. there are erroneous "garbage" digits

- 1. Idea of 1/10th, this is mathematically pure

- 2. In Python code: looks like this

0.1

- 3. In the computer memory, actually:

0.100000000000076

- There are some garbage digits way off to the right

- The float math will not come out exactly right

- This is a deep feature of computer floats, applies to all languages

- The print routine hides a few digits, so often the garbage is hidden

But in the computation, the garbage is there

Crazy Flaw Demo - Printing Omits

- Garbage digits are very often part of a float value

- Printing omits a few stored digits at right

- So often you do not see the garbage digits

- But eventually the garbage gets big enough to print

- This makes a memorable demo

>>> 0.1

0.1

>>> 0.1 + 0.1

0.2

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 # this is why we can't have nice things

0.30000000000000004

>>>

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

0.4

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

0.5

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

0.6

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

0.7

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

0.7999999999999999 # here the garbage is negative

Another example with 3.14

>>> 3.14 * 3

9.42

>>> 3.14 * 4

12.56

>>> 3.14 * 5

15.700000000000001 # d'oh

Summary: float math is slightly wrong

Why Must We Have This Garbage?

The short answer, is that with a fixed number of bytes to store a floating point number in memory, there are some unavoidable problems where numbers have these garbage digits on the far right. It is similar to the way the number 1/3 is not possible to write it out precisely as a decimal number.

Crazy, But Not Actually A Problem

- Everyone needs to remember:

- float arithmetic always comes out a tiny bit wrong

- (int arithmetic, comes out perfect)

- The error is typically far less than 1-trillionth part

- But the error is not zero

- Most computations can handle an error of 1-trillionth part

- Actually not a problem

- How many digits of accuracy in the inputs, 6 digits?

- Suppose you are working on a mars orbiter

How accurate is, say, the radar measuring distance to mars

Say it has 6 digits of accuracy .. that swamps the float error

Must Avoid One Thing: no ==

- There is one concrete coding rule

- Do not use == with float numbers

>>> a = 3.14 * 5

>>> b = 3.14 * 6 - 3.14

>>> a == b # Observe == not working right

False

>>> b

15.7

>>> a

15.700000000000001

- abs(x) - the absolute value function

- Instead of ==, look at abs(a-b)

>>> abs(a-b) < 0.00001

True

- Exception: 0.0 is reliable for ==

- Any float value * 0.0 will be exactly 0.0

Float Conclusions

- 1. Two systems, int 67 and float 3.14

- 2. Math works for both int/float seamlessly

- 3. Float has tiny error many digits to the right, don't use ==

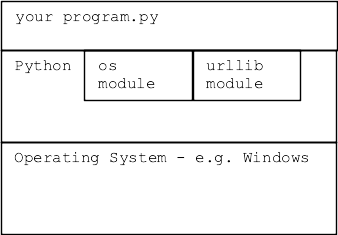

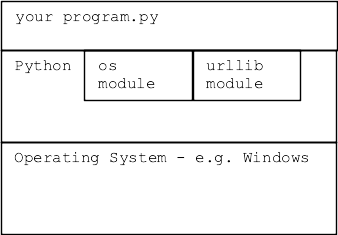

Modules and Modern Coding

Modules hold code for common problems, ready for your code to use. We say that you build your code "on top of" the libraries. Modern coding is part custom, and part building on top of module code.

We ♥ Modules

- Question while coding:

Is part of this solved in a module already?

- Using module code you didn't have to write is very attractive

- (This is kind of a no-brainer case to make!)

- Somebody else wrote it, you can just use it

- It's well tested

- It has real docs

- Your teammates may already be familiar with it

- CS106A we see this "module" theme a little

CS106A needs to cover fundamentals

loops, strs, dicts, files ..

Courses beyond CS106A, you will probably spend more time using modules

Python "module" - Name + Code

- A Python module contains lots of functions, solving common problems

- Every module has a name

- e.g. "math" module contains math functions

- e.g. "random" module contains functions for pseudo-random numbers=

- e.g. "urllib" module contains functions for urls and web requests

Syntax 1: import math

- To use a module, include a

import math line

- Import the module by its name

- Typically these are grouped near the top of your file

Syntax 2: math.sqrt(2)

- On later lines, refer to functions in the module with a dot

- e.g.

math.sqrt(2)

- e.g.

random.randrange(10)

- Readable: in this way, it's clear when calling a function..

that it is coming from that module

- There are other ways of doing import, but this import + math.sqrt() was is the simplest

>>> import math

>>> math.sqrt(2) # call sqrt() fn

1.4142135623730951

>>> math.sqrt

>>>

>>> math.log(10)

2.302585092994046

>>> math.pi # constants in module too

3.141592653589793

Quit and restart the interpreter without the import, see common error:

>>> # quit and restart interpreter

>>> math.sqrt(2) # OOPS forgot the import

Traceback (most recent call last):

NameError: name 'math' is not defined

>>>

>>> import math

>>> math.sqrt(2) # now it works

1.4142135623730951

Random Module Exercise

Try "random" module. Import it, call its "randrange(20)" function.

>>> import random

>>>

>>> random.randrange(4)

3

>>>

Module = Dependency

- When you write code using a module

- Your code now depends on that module's existence

- If that module disappeared, your code would stop working

1. "Standard" Modules

- Standard = included/maintained as part of Python3 install

- These are the best modules to use

- Can rely on this module now and in the future

Very rare for a module to be dropped

- No separate install is required

- The standard module is installed when python is installed

Many Standard Modules

- Do not: memorize whole list of modules

- Do: check the list for help when starting a project

- Standard Python Modules List

- A few examples...

- math module of math functions, e.g. math.cos()

- email module for creating and parsing email messages

- random module for creating pseudo random numbers

- os module for listing directories, creating files

- datetime module of calendar functions

- zipfile module for reading/creating .zip files

- urllib module for making http requests, using data

2. Non-Standard "pip" Modules

Other modules are valuable but they are not a standard part of Python. For code using non-standard module to work, the module must be installed on that computer via the "pip" Python tool. e.g. for homeworks we had you pip-install the "Pillow" module with this command:

$ python3 -m pip install Pillow

..prints stuff...

Successfully installed Pillow-5.4.1

A non-standard module can be great, although the risk is harder to measure. The history thus far is that popular modules continue to be maintained. Sometimes the maintenance is picked up by a different group than the original module author.

Module Docs

- Every module has formal "documentation" - "docs"

- Explain what functions do

- The "abstraction" of each function

- -what it does

- -how to call it

- Demo web search: "python math module"

- python.org - the official home of python docs, watch out for SEO

-Search Engine Optimization

-Some possibly lame site tries to get a better search ranking

Gets python.org math docs

Hacker: Use dir() and help() (optional)

- Feel like a hacker, use dir() and help() on module

- In the interpreter >>>

dir(module) - shows a list of all the defs in the module

help(module.fn) - shows some help text for that function

- The """Pydoc""" we write to describe each function

- That Pydoc is what help() returns (demo later)

>>> import math

>>> dir(math)

['__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'acos', 'acosh', 'asin', 'asinh', 'atan', 'atan2', 'atanh', 'ceil', 'copysign', 'cos', 'cosh', 'degrees', 'e', 'erf', 'erfc', 'exp', 'expm1', 'fabs', 'factorial', 'floor', 'fmod', 'frexp', 'fsum', 'gamma', 'gcd', 'hypot', 'inf', 'isclose', 'isfinite', 'isinf', 'isnan', 'ldexp', 'lgamma', 'log', 'log10', 'log1p', 'log2', 'modf', 'nan', 'pi', 'pow', 'radians', 'remainder', 'sin', 'sinh', 'sqrt', 'tan', 'tanh', 'tau', 'trunc']

>>>

>>> help(math.sqrt)

Help on built-in function sqrt in module math:

sqrt(x, /)

Return the square root of x.

>>>

>>> help(math.cos)

Help on built-in function cos in module math:

cos(x, /)

Return the cosine of x (measured in radians).

wordcount.py Is a Module

How hard is it to write a module? Not hard at all. A regular foo.py file also works as a module with whatever defs the foo.py file has.

Consider the file wordcount.py in wordcount.zip

Forms a module named wordcount

- Suppose you have built some useful functions

- Someone else in your lab wants to use them....

Them pasting in their own copy is not ideal

- What does a module contain?

- We have wordcount.py

- python3 wordcount.py - runs main()

- wordcount.py is also a module named just "wordcount"

- Think of all the defs in wordcount: read_counts(), clean(), print_counts(),

- import works on wordcount (in the same directory)

- Access functions as module.xxx just like usual

- Run python interpreter in wordcount directory to try this

- Try importing wordcount, calling the read_counts() function

- Call wordcount.clean()

Try this demo in the wordcount directory

>>> # Run interpreter in wordcount directory

>>> import wordcount

>>>

>>> wordcount.read_counts('test1.txt')

{'a': 2, 'b': 2}

- A module/file contains many defs

- Can import a module/file, call its defs:

- module.fn_name()

- Style: for a function to be usable from another module...

it should take in data as parameters and return a value

i.e. black box style

we've done this all along, see now the bigger picture

- Babygraphics project:

treats babynames.py as a module

import babynames

calls babynames.read_files()

dir() and help() work on wordcount Too

- Look at wordcount.py, look at the functions

- dir() and help() work here too

- See where the """Pydoc""" goes!

>>> dir(wordcount)

['__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'clean', 'main', 'print_counts', 'print_top', 'read_counts', 'sys']

>>>

>>> help(wordcount.read_counts)

Help on function read_counts in module wordcount. The text here comes from the """Pydoc""" you write at the top of a function.

read_counts(filename)

Given filename, reads its text, splits it into words.

Returns a "counts" dict where each word

...

Babynames Module Example

# 1. In the babygraphics.py file

# import the babynames.py file in same directory

import babynames

...

# 2. Call the read_files() function

names = babynames.read_files(FILENAMES)

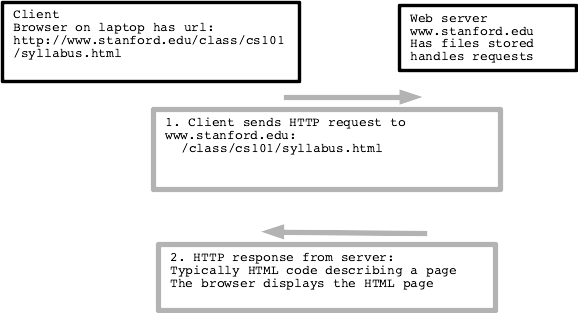

Module Example: urllib

- Look at how web pages work

- Then play with urllib

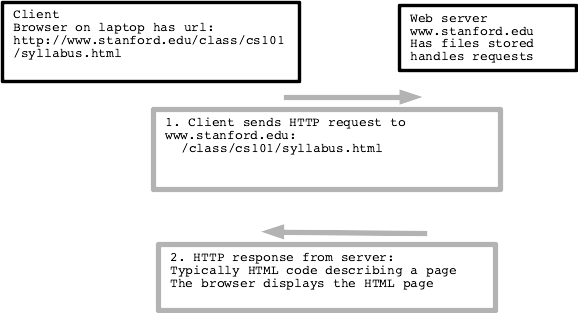

How Does The Web Work?

- The web browser app has url ("client" side)

- Web server is running on some machine ("server" side)

- Browser sends GET request to server

- Server gets request, sends back HTML response data

- HTML is a text code

- Browser "renders" the HTML on screen

- Common request/response data types: HTML JPEG PNG GIF SVG

- Video formats MPEG4 h.265 (crazy patent problems)

- New open format "AV1" .. you heard it here first!

- Demo:

Visit python.org or sfgate.com or whatever

Right-click on page, "View Source" to see the HTML text that makes a web page

- Think of all the surfing you have done .. HTML code defines each page

HTML

Here is the HTML code for is plain text with a bolded word in it, tags like <b> mark up the text.

This <b>bolded</b> text

HTML Experiment - View Source

Go to python.org. Try view-source command on this page (right click on page). Search for a word in the page text, such as "whether" .. to find that text in the HTML code.

Thing of how many web pages you have looked at - this is the code behind those pages. It's a text format! Lines of unicode chars!

urllib Demo

- Python code to request an HTML page by url

- urllib - making requests to a server, getting back data

- An example of using a standard module

- docs - urllib.request docs on python.org

- Makes a URL look like a local file mostly

- Read the text of the web page

- Use s.find() to display a fragment of it

>>> import urllib.request

>>> f = urllib.request.urlopen('http://www.python.org/')

>>> text = f.read().decode('utf-8')

>>> text.find('Whether')

26997

>>> text[26997:27100]

"Whether you're new to programming or an experienced developer, it's easy to learn and use Python.\r\n"

- f.read() works once, returning bytes

- decode('utf-8') decode raw bytes -> unicode string

- Does not always work, they may be blocking python on purpose

- f.read() - all the bytes

- r.read(300) - just first 300 bytes

- Can try http: or https: for these

>>> import urllib.request

>>> f = urllib.request.urlopen('http://www.python.org/')

>>> text = f.read().decode('utf-8')

>>> # text is the HTML

>>> # use text.find('xxx') to look for something, show that slice

>>> # like text[5000:5200]

>>>

>>> f = urllib.request.urlopen('https://sfgate.com/')

>>> text = f.read().decode('utf-8')

# without >>>, for copy/paste

import urllib.request

f = urllib.request.urlopen('http://www.python.org/')

text = f.read().decode('utf-8')