Today: string in, if/elif, string .find(), slices

See chapters in Guide: String - If

in Test>>> 'Dog' in 'CatDogBird' True >>> 'dog' in 'CatDogBird' # upper vs. lower case False >>> 'd' in 'CatDogBird' # finds d at the end True >>> 'atD' in 'CatDogBird' # not picky about words True >>> >>> 'x' in 'CatDogBird' False

not inThere's also a not in form which is True if the element is not in there, like !=. Use this, say for an if-statement where you want to take an action if something is not in a string.

>>> s = 'CatDogBird'

>>> if 'x' not in s: # YES this way

print('no x')

no x

>>>

>>> if not 'x' in s: # NO works but not PEP8

print('no x')

no x

>>>

Using not in is preferred for this case vs. the form not 'x' in s

has_pi(s): Given a string s, return True if it contains the substrings '3' and '14' somewhere within it, but not necessarily together. Use "in".

> has_pi()

Note these functions are in the string-3 section on the Experimental server

This form looks right in English but does not work in Python or most computer languages:

if '3' and '14' in s: # NO does not work

...

The and should connect two fully formed boolean tests, such as you would write with "in" or "==", so this works

if '3' in s and '14' in s:

...

Python has many built-in functions, like "in", and we will see all the important ones in CS106A. You want to know the common built-in functions, since using a built-in is far preferable to writing code for it yourself - "in" is a nice example. The "in" operator works for several data structure to see if a value is in there, and its use with strings is our first example of it. It also can in some cases run faster than what you could code yourself.

> catty()

'xaCtxyzAx' -> 'aCtA'

Return a string made of the chars from the original string, whenever the chars are one of 'c' 'a' 't', (not case sensitive).

Here is a natural way to think of the code, but it does not work:

def catty(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i] == 'c' or s[i] == 'a' or s[i] == 't':

result += s[i]

return result

What is the problem? Upper vs. lower case. We are not getting any uppercase chars 'C' for example.

Solution: convert each char to lowercase form .lower(), then test.

Solution - this works, but that if-test is quite long, can we do better? Indeed, it's so long, it's awkward to fit on screen.

Aside: see style guide breaking up long lines for way to break up long lines like this.

def catty(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].lower() == 'c' or s[i].lower() == 'a' or s[i].lower() == 't':

result += s[i]

return result

Start with the v2 code. Create variable to hold the repeated computation - shorten the code and it "reads" better with the new variable.

low = s[i].lower()

The complete solution

def catty(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

low = s[i].lower() # decomp by var

if low == 'c' or low == 'a' or low == 't':

result += s[i]

return result

We will use this strategy frequently with CS106A code. If the solution is getting a little lengthy, introduce a variable for some sub-part of the computation like this.

The name of a variable should label that value in the code, helping the programmer to keep their ideas straight. Other than that, the name can be short. The name does not need to repeat every true thing about the value. Just enough to distinguish it from other values in this algorithm.

1. Good names for this example, short but with key facts: low, low_char

2. Names with more detail, probably too long: low_char_i, low_char_in_s

3. Avoid this name: lower - name is ok, but avoid using a name which is the same as the name of a function, just to avoid confusion.

The V2 code above is acceptable, but V3 is shorter and nicer. The V3 code also runs slightly faster, as it does not needlessly re-compute the lowercase form three times per char.

This is just coding trick, not something we would ever require or look for students to do. The in can be do the "or" logic for us, like this:

# instead of this

if low == 'c' or low == 'a' or low == 't':

...

# this works - a trick use of "in"

if low in 'cat':

...

if and if/else:if/elifif test1: action1 elif test2: action2 elif test3: action3 else: action4 # Tries test1, if that's False, tries test2, # if that's False, tries test3, and so on.

The most common letters used in English text are: e, t, a, i, o, n

Here we process string s, swapping around the 3 vowels like this:

e -> a a -> i i -> e

This changes an English word in a way that looks like a word and is kind of funny.

'kitten' -> 'kettan' 'table' -> 'tibla' 'radio' -> 'rideo'

vowel_swap(s): Given string s. We'll swap around the three most common vowels in English, which are 'e', 'a', and 'i'. Return a form of s where each lowercase 'e' is changed to 'a', each 'a' is changed to 'i', and each 'i' is changed to 'e'. Other chars leave unchanged. So the word 'kitten' returns 'kettan'. Use an if/elif structure. The basic string loop is provided.

def vowel_swap(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i] == 'e':

result += 'a'

elif s[i] == 'a':

result += 'i'

elif s[i] == 'i':

result += 'e'

else:

result += s[i]

return result

The use of return can accomplish something similar to the if/elif structure, which is why we have not really needed if/elif. Suppose we are doing the vowel-swap algorithm, but in a function that processes a single char. This code works perfectly without using if/elif:

def swap_ch(ch):

"""Vowel-swap on one char."""

if ch == 'e':

return 'a'

if ch == 'a':

return 'i'

if ch == 'i':

return 'e'

return ch

Since the return exits the function - we get the if/elif feature that once a test is taken, the later tests are skipped.

However, the full-string vowel_swap() above cannot use return like this, as it needs to keep running the loop to do the other characters. We need to handle each char in the loop but without leaving the function, and for that, the if/elif is perfect.

str_adx(s): Given string s. Return a string of the same length. For every alphabetic char in s, the result has an 'a', for every digit a 'd', and for every other type of char the result has an 'x'. So 'Hi4!x3' returns 'aadxad'. Use an if/elif structure.

Solution

def str_adx(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isalpha():

result += 'a'

elif s[i].isdigit():

result += 'd'

else:

result += 'x'

return result

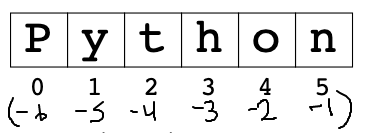

>>> s = 'Python'

>>>

>>> s.find('th')

2

>>> s.find('o')

4

>>> s.find('y')

1

>>> s.find('x')

-1

>>> s.find('N')

-1

>>> s.find('P')

0

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[1:3] # 1 .. UBNI 'yt' >>> s[1:5] 'ytho' >>> s[4:5] 'o' >>> s[4:4] # "not including" dominates ''

>>> s[:3] # omit = from/to end 'Pyt' >>> s[4:] 'on' >>> s[4:999] # too big = through the end 'on' >>> s[:4] # "perfect split" on 4 'Pyth' >>> s[4:] 'on' >>> s[:] # the whole thing 'Python'

A first venture into using index numbers and slices. Many problems work in this domain - e.g. extracting all the hashtags from your text messages.

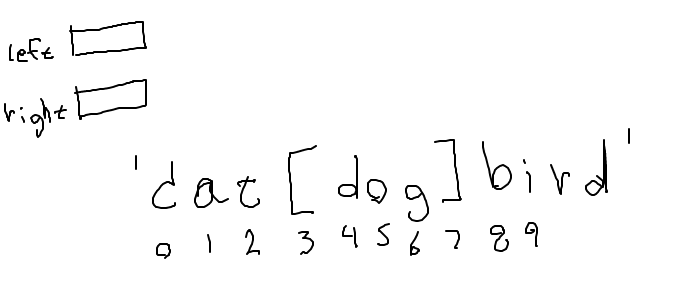

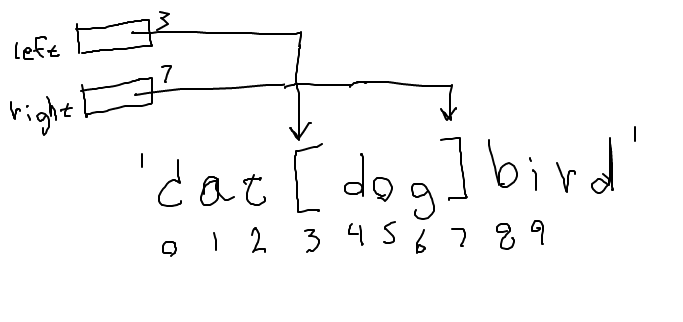

'cat[dog]bird' -> 'dog'

> brackets

brackets(s): Look for a pair of brackets '[...]' within s, and return the text between the brackets, so the string 'cat[dog]bird' returns 'dog'. If there are no brackets, return the empty string. If the brackets are present, there will be only one of each, and the right bracket will come after the left bracket.

def brackets(s):

left = s.find('[')

if left == -1:

return ''

right = s.find(']')

return s[left + 1:right]

We prefer "readable" code — when the eye sweeps over the code, what the code does is apparent. In this case, the named variables help make the code readable. Look at that last line, how the variables help spell out how the slice pulls in the data from the previous lines. Code that is readable as you write it contains fewer bugs.

The variables left and right are a very natural example of decomp-by-var. In the code, the variables name an intermediate value that runs through the computation.

Below is what the code looks like without the variables. It works fine, and it's one line shorter, but the readability is clearly worse. It also likely runs a little slower, as it computes the left-bracket index twice.

def brackets(s):

if s.find('[') == -1:

return ''

return s[s.find('[') + 1: s.find(']')]

The first solution with its variables looks better and is more readable.

We have seen many examples of int indexing to access a part of a structure. So of course doing it slightly wrong is very common as well. So common, there is a phrase for it - "off by one error" or OBO — it even has its own wikipedia page. You can feel some kinship with other programmers each time you stumble on one of these.

"My code is perfect! Why is this not working? Why is this not work ... oh, off by one error. We meet again!"

Why do you need to think of new ways for your code to go wrong when the old ways work so well!

> at_3

Here is a problem similar to brackets for you to try. If we have enough time in lecture, we'll do it in lecture. A drawing really helps the OBO on this one.

Milestone-1 - get the 'abc' output below, not worrying about if the input is too short

Milestone-2 - add logic for the too-short case. Note the i < len(s) valid idea below.

at_3(s): Given string s. Find the first '@' within s. Return the len-3 substring immediately following the '@'. Except, if there is no '@' or there are not 3 chars after the '@', return ''.

'xx@abcd' -> 'abc' 'xxabcd' -> '' 'x@x' -> ''

i < len(s)More s.find() if we have time...

s.find() variant with 2 params: s.find(target, start_index) - start search at start_index vs. starting search at index 0. Returns -1 if not found, as usual. Use to search in the string starting at a particular index.

Suppose we have the string '[xyz['. How to find the second '[' which is at 4? Start the search at 1, just after the first bracket:

>>> s = '[xyz['

>>> s.find('[') # find first [

0

>>> s.find('[', 1) # start search at 1

4

> parens()

'x)x(abc)xxx' -> 'abc'

This is nice, realistic string problem with a little logic in it.

Thinking about this input: '))(abc)'. Starting hint code, something like this, to find the right paren after the left paren:

left = s.find('(')

...

right = s.find(')', left + 1)

>>> s = 'Python' >>> s[len(s) - 1] 'n' >>> s[-1] # -1 is the last char 'n' >>> s[-2] 'o' >>> s[-3] 'h' >>> s[1:-3] # works in slices too 'yt' >>> s[-3:] 'hon'