Today: foreach loop instead of for/i/range, start lists, how to write main()

for i in range(len(s)):

# Use s[i]

We've used this many times and we'll continue to.

So many memories! Looping over string index numbers.

for i in range(len(s)):

Looping over x values in an image

for x in range(image.width):

Looping over y values in an grid:

for y in range(grid.height):

Looping over index numbers like this is an important code pattern and we'll continue to use it.

BUT now we're going to see another way to do it!

for ch in s:A "foreach" loop can loop over a string and access each char directly. We are not bothering with index numbers, but pointing the variable at each char directly. This is easier than the for/i/range form above. In the loop, the ch variable points to each char, one per iteration:

'H' 'e' 'l' 'l' 'o'

s = 'Hello'

for ch in s:

# Use ch in here

Like earlier double_char(), but using the foreach for/ch/s loop form. The variable ch points to one char for each iteration.

Note: no index numbers, no []

def double_char2(s):

result = ''

for ch in s:

result = result + ch + ch

return result

We have for ch in s: - "foreach"

We have for i in range(len(s)): - "for/i/range"

We will end up using both of these in different situations. How do you know which loop to use?

1. Use for ch in s: if you need each char but not its index number. This is the easier option, so we are happy to use it where it's good enough.

Above double_char(s) is an example - needed each char but did not need index numbers.

2. Use the for i in range(len(s)): if you need each char and also its index number. The find_alpha() function below is an example.

'66abc77' -> 2 '!777' -> -1

find_alpha(s): Given a string s, return the index of the first alphabetic char in s, or -1 if there are none. Use a for/i/range loop.

Q: Do we need index numbers for this? Yes. We need the index number in the loop so we can return it, just having 'a' from '66abc77' is not enough. Need the 2. Therefore use for/i/range.

This is also an example of an early return strategy — return out of the middle of the loop if we find the answer, not doing the rest of the iterations. Then the return after the end of loop is for the did-not-find case.

def find_alpha(s):

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isalpha():

return i # need index here

return -1

'12ab3' -> 6 '777' -> 21 'abcd' -> 0

Revisit this problem, now do it with foreach. Recall also str/int conversion.

sum_digits2(s): Given a string s. Consider the digit chars in s. Return the arithmetic sum of all those digits, so for example, '12abc3' returns 6. Return 0 if s does not contain any digits.

Q: Do we need the index number of each char to compute this? No, we just need each char. Therefore foreach is sufficient.

def sum_digits2(s):

sum = 0

for ch in s:

if ch.isdigit():

num = int(ch) # '7' -> int 7

sum += num

return sum

Does not need index numbers. Demonstrates both foreach and in

difference(a, b): Given two strings, a and b. Return a version of a, including only those chars which are not in b. Use case-sensitive comparisons. Use a for/ch/s loop.

def difference(a, b):

result = ''

# Look at all chars in a.

# Check each against b.

for ch in a:

if ch not in b:

result += ch

return result

Additional exercise - string intersect:

See the guide: Python List for more details about lists

See the "list1" for examples below on the experimental server

['aa, 'bb', 'cc', 'dd']len(lst)Use square brackets [..] to write a list in code (a "literal" list value), separating elements with commas. Python will print out a list value using this same square bracket format.

The len() function works on lists, same as strings.

The "empty list" is just 2 square brackets with nothing within: []

>>> lst = ['aa, 'bb', 'cc', 'dd'] >>> lst ['aa, 'bb', 'cc', 'dd'] >>> >>> len(lst) 4 >>> lst = [] # empty list >>> len(lst) 0 >>>

Use square brackets to access an element in a list. Valid index numbers are 0..len-1. Unlike string, you can assign = to change an element within the list.

>>> lst = ['aa, 'bb', 'cc', 'dd'] >>> lst[0] 'aa' >>> lst[2] 'cc' >>> >>> lst[0] = 'apple' # Change elem >>> lst ['apple', 'bb', 'cc', 'dd'] >>> >>> >>> lst[9] Error:list index out of range >>>

The big difference from strings is that lists are mutable - lists can be changed. Elements can be added, removed, changed over time.

lst.append('thing')# Common list-build pattern: # Make empty list, then call .append() on it >>> lst = [] >>> lst.append(1) >>> lst.append(2) >>> lst.append(3) >>> >>> lst [1, 2, 3] >>> len(lst) 3 >>> lst[0] 1 >>> lst[2] 3 >>> >>> # 2. Say we want a list of 0, 10, 20 .. 90 >>> # Write for/i/range loop, use append() inside >>> nums = [] >>> for i in range(10): ... nums.append(i * 10) ... >>> nums [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90] >>> len(nums) 10 >>> nums[5] 50

> list_n()

list_n(n): Given non-negative int n, return a list of the form [0, 1, 2, ... n-1]. e.g. n=4 returns [0, 1, 2, 3] For n=0 return the empty list. Use for/i/range and append().

Note: This is a case of using for/i/range to generate a bunch of numbers

def list_n(n):

nums = []

for i in range(n):

nums.append(i)

return nums

'nom'Change the list_n code to append 'nom' in the loop instead of a number. what does the resulting list look like for each value of n? This also shows that the list can as easily contain a bunch of strings as a bunch of ints.

lst = lst.append()The list.append() function modifies the existing list. It returns None. Therefore the following code pattern will not work, setting lst to None:

# NO does not work lst = [] lst = lst.append(1) lst = lst.append(2) # Correct form lst = [] lst.append(1) lst.append(2) # lst points to changed list

Why would someone write lst = lst.append(1)? Because we are accustomed to x = change(x) for strings, but that pattern does not work for lists.

+=Don't use += on lists for now. It works for strings, but += is not the same as .append() for list. We may show what it does later, but for now just avoid it.

Correct way to add to list:

lst.append('thing')

>>> lst = ['aa', 'bb', 'cc', 'dd'] >>> 'cc' in lst True >>> 'x' in lst False >>> 'x' not in lst # preferred form to check not-in True >>> not 'x' in lst # equivalent, not preferred True

How to loop over the elements in a list? The foreach loop works.

>>> lst = ['aa', 'bb', 'cc', 'dd'] >>> for s in lst: ... # Use s in here ... print(s) ... aa bb cc dd

The word after for is the name of a variable for the loop to use. Choose the var name to reflect type of element, s for a string, n for a number. This helps you fill in the loop body correctly.

# list of strings for s in strs: ... # list numbers for n in nums: ... # list of urls for url in urls: ...

intersect(a, b): Given two lists of numbers, a and b. Construct and return a new list made of all the elements in a which are also in b.

This code is similar to string algorithms, using list versions of features such as foreach, "in", and append().

Minor point: since it's a list of numbers, we'll use num as the variable name in the foreach over this list.

The intersect() code is a good example of what people like about Python — - letting us express our algorithmic ideas with minimal fuss. Also shows our preference for using builtin functions, in this case "in", to do the work for us when possible.

def intersect(a, b):

result = []

for num in a:

if num in b:

result.append(num)

return result

>>> lst = ['aa', 'bb', 'cc', 'dd']

>>> lst.index('cc')

2

>>> lst.index('x')

ValueError: 'x' is not in list

>>> 'x' in lst

False

>>> 'cc' in lst

True

>>>

>>> # Like this:

>>> # check "in" before .index()

>>> if 'x' in lst:

print(lst.index('x'))

>>>

donut_index(foods): Given "foods" list of food name strings. If 'donut' appears in the list return its int index. Otherwise return -1. No loops, use .index(). The solution is quite short.

e.g. foods = ['apple', 'donut', 'banana'].

Return index in the list of 'donut', or -1 if not found?

def donut_index(foods):

if 'donut' in foods:

return foods.index('donut')

return -1

list_censor(n, censor): Given non-negative int n, and a list of "censored" int values, return a list of the form [1, 2, 3, .. n], except omit any numbers which are in the censor list. e.g. n=5 and censor=[1, 3] return [2, 4, 5]. For n=0 return the empty list.

Solution

def list_censor(n, censor):

nums = []

for i in range(n):

# Introduce "num" var since we use it twice

# Use "in" to check censor

num = i + 1

if num not in censor:

nums.append(num)

return nums

As your algorithms grow more complicated, with three or four variables running through your code, it can become difficult to keep straight in your mind which variable, say, is the number and which variable is the list of numbers. Many little bugs have the form of wrong-variable mixups like that.

Therefore, an excellent practice is to name your list variables ending with the letter "s", like "nums" above, or "urls" or "weights".

urls = [] # name for list of urls url = '' # name for one url

Then when you have an append, or a loop, you can see the singular and plural variables next to each other, reinforcing that you have it right.

url = (some crazy computation)

urls.append(url)

Or like this

for url in urls:

...

STATES = ['CA, 'NY', 'NV', 'KY', 'OK']

...

...

def some_fn():

# can use STATES in here

for state in STATES:

...

# provided ALPHABET constant - list of the regular alphabet

# in lowercase. Refer to this simply as ALPHABET in your code.

# This list should not be modified.

ALPHABET = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z']

...

def foo():

for ch in ALPHABET: # this works

print(ch)

You have called your code from the command line many times. The function main() is typically the first function to run in a python program, and its job is looking at the command line arguments and figuring out how to start up the program. With HW4, it's time for you to write your own main(). You might think it requires some advanced CS trickery, but it's easier than you might think.

For details see guide: Python main() (uses affirm example too)

affirm.zip Example/exercise of main() command line args. You can do it yourself here, or just watch the examples below to see the ideas.

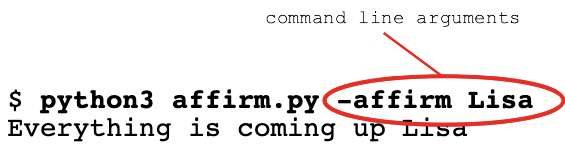

First run affirm.py, see what the command line arguments (aka "args") it takes:

-affirm and -hello options (aka "flags")

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa Everything is coming up Lisa $ python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart Looking good Bart $ python3 affirm.py -affirm Maggie Today is the day for Maggie $ python3 affirm.py -hello Bob Hello Bob $

-affirmThe command line arguments, or "args", are the extra words typed on the command line to tell the program what to do. The system is deceptively simple - the command line arguments are just the words after the program.py on the command line. So in this command line:

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

The words -affirm and Lisa are the 2 command line arguments. They are separated from each other by spaces on the command line.

main() has args Python ListWhen a Python program starts running, typically the run begins in the function named main(). This function can look at the command line arguments, and figure out what functions to call. (Other computer languages also use this convention - main() is the first to run.)

In our main() code, the variable args is set up as a Python list containing the command line args. Each arg is a string - just what was typed on the command line. So the args list communicates to us what was typed on the command line.

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Lisa

....

e.g. args == ['-affirm', 'Lisa']

$ python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

....

e.g. args == ['-affirm', 'Bart']

Edit the file affirm-exercise.py. In the main() function, find the args = .. line which sets up the args list. Add the following print() - this just prints out the args list so we can see it. We can remove this print() later.

args = sys.argv[1:]

print('args:', args) # add this

Now run the program, trying a few different args, so you see what the args list is depending on what is typed.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -affirm Bart args: ['-affirm', 'Bart'] $ python3 affirm-exercise.py -affirm Lisa args: ['-affirm', 'Lisa'] $ python3 affirm-exercise.py -hello Hermione args: ['-hello', 'Hermione']

Q: For the Hermione line: what is args[0]? what is args[1]?

print_affirm(name) Helpers ProvidedWe have helper functions already defined that do the various printouts:

print_affirm(name) - prints affirmation for name

print_hello(name) - print hello to name

print_n_copies(n, name) - given int n,

print n copies of name

Their code is shown below. They are not too complex. Also see that AFFIRMATIONS is defined as a constant - the random affirmation strings to use.

AFFIRMATIONS = [

'Looking good',

'All hail',

'Horray for',

'Today is the day for',

'I have a good feeling about',

'A big round of applause for',

'Everything is coming up',

]

def print_affirm(name):

"""

Given name, print a random affirmation for that name.

"""

affirmation = random.choice(AFFIRMATIONS)

print(affirmation, name)

def print_hello(name):

"""

Given name, print 'Hello' with that name.

"""

print('Hello', name)

def print_n_copies(n, name):

"""

Given int n and name, print n copies of that name.

"""

for i in range(n):

# Print each copy of the name with space instead of \n after it.

print(name, end=' ')

# Print a single \n after the whole thing.

print()

We'll do this one lecture.

Make this command line work, editing the file affirm-exercise.py:

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -affirm Lisa

Solution code

def main():

args = sys.argv[1:]

....

....

# 1. Check for the -affirm arg pattern:

# python3 affirm.py -affirm Bart

# e.g. args[0] is '-affirm' and args[1] is 'Bart'

if len(args) == 2 and args[0] == '-affirm':

print_affirm(args[1])

Solution Notes

Write if-logic in main() to looking for the following command line form, call print_hello(name), passing in correct string.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -hello Bart

Solution code

if len(args) == 2 and args[0] == '-hello':

print_hello(args[1])

In this case, the function to call is print_n_copies(n, name), where n is an int param, and name is the name to print. Note that the command line args are all strings, so there is a tricky issue there.

$ python3 affirm-exercise.py -n 10000 Hermione