Today: advanced double-while parsing, python copying, nesting, flex-arrow drawing example, 1940

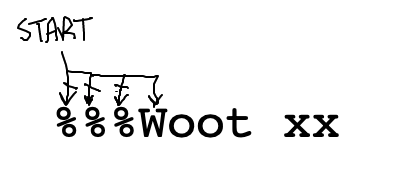

We've done them like this:

at end v----v xx @word xx

I will work this one in lecture with the double-while technique. Then we'll have you try to solve a similar one. (HW5)

find_alpha(s): We'll say a word is made of 1 or more alphabetic chars. Find and return the first word in s, or None if there is none. So '%%%abc xx' returns 'abc'. Use two while loops.

%%%Woot xx nnn♥♥♥♥nnn

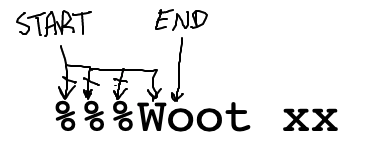

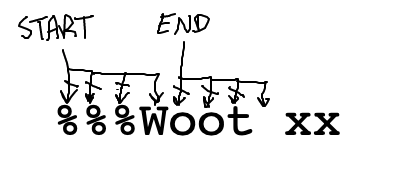

Work this out with an example in the make-a-drawing tradition

1. Set start = 0

2. Advance start over the '%' to find the 'W'

# Advance start to first alpha

start = 0

while start < len(s) and not s[start].isalpha():

start += 1

Q: Suppose there is no alpha. What will start be after loop 1? What is the if-check for that case?

Reminder: here is the loop-1 code:

while start < len(s) and not s[start].isalpha(): start += 1

Sketch out what start does for the no-alpha case:

'%%%' 0123

if start == len(s):

return None

def find_alpha(s):

# Advance start to first alpha

start = 0

while start < len(s) and not s[start].isalpha():

start += 1

# There was no word

if start == len(s):

return None

# Advance end past alpha chars

end = start + 1

while end < len(s) and s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

return s[start:end]

The find_num() - complicated, but like the lecture example, see if you can do it. Drawings below to get your thoughts started. Fine if you don't handle the "no numbers found" case at first.

find_num(s): We'll say that a number is a series of one or more digit chars. Find and return the substring of the first num in s, or None if there is none.

'xx$123WW' -> '123'

Loop 1 - advance start to first digit:

while start < len(start) and ???:

start += 1

start v 'xx$123WW'

Loop 2 - advance end past digits:

while end < len(s) and ???:

end += 1

end

v

'xx$123WW'

def find_num(s):

# Advance start to first digit

start = 0

while start < len(s) and not s[start].isdigit():

start += 1

# There was no num

if start == len(s):

return None

# Advance end past digits

end = start + 1

while end < len(s) and s[end].isdigit():

end += 1

return s[start:end]

This is a little more difficult than then find_alpha() example. Try this one if you get stuck on the homework.

'xx$aba xx' -> 'aba'

find_abba(s): We'll say an "abba" word is just made of 'a' and 'b' chars. Find and return the first abba word in s, or the empty string if there is not one. Use two while loops.

Notice that we don't have some unrealistic constraint that there's always an '@' to start the word - the word is just sitting in s and we need to find it.

To get you started, think about the first loop for find_abba() - advancing start to the start of the abba word. This is the not ♥ loop.

Code

start = 0

while start < len(s) and ???:

start += 1

Some drawings to think about this problem.

Loop 1 - find start:

start v 'xx$aba x'

Or this one:

start v 'xx$bab x'

Loop 2 - advance end

Code

while end < len(s) and ???:

end += 1

end

v

'xx$aba x'

The first loop, advance start while char is not 'a' and char is not 'b'. The "or" is soooo tempting here. Just in your head, try that approach on the cases above to see why it's "and".

# Advance start to first abba char

start = 0

while start < len(s) and s[start] != 'a' and s[start] != 'b':

start += 1

Then the loop to find the end of the abba uses "or" and parenthesis, since we have a combination of and/or:

# Advance end past abba chars

end = start + 1

while end < len(s) and (s[end] == 'a' or s[end] == 'b'):

end += 1

The whole solution

def find_abba(s):

# Advance start to first abba char

start = 0

while start < len(s) and s[start] != 'a' and s[start] != 'b':

start += 1

# There was no abba

if start == len(s):

return ''

# Advance end past abba chars

end = start + 1

while end < len(s) and (s[end] == 'a' or s[end] == 'b'):

end += 1

return s[start:end]

Next week we'll pursue examples where structures nested inside of other structures, such as lists inside of lists.

We'll introduce the most basic ideas today to get started down this path.

We've used square brackets many times to pull a thing out of a string or list. In the next section, we'll use square brackets in a complex scene. The function of the square bracket will be 100% the same as it has been, so let's get that clear in everyone's mind first.

Say we have this list:

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c'] >>>

'c' How?Q: How to access 'c' from that list?

A: The 'c' is at index 2 in the list. Therefore: lst[2] is a reference (arrow) to the element at index 2.

>>> lst[2] 'c'

'c' How?Set a variable s = lst[2] - now it points to the 'c'. Thereafter, both s and lst[2] are ways to refer to the 'c' - they are equivalent.

>>> s = lst[2] >>> s 'c' >>> lst[2] 'c'

a = b in GeneralAssigning a variable like a = b - sets a to point to the same thing that the expression b points to. Both now point to the same thing.

The following two print() calls are deeply the same:

>>> print(lst[2]) c >>> print(s) c >>>

Suppose I have a list variable "outer". Inside this list are lists of numbers.

The list .append() function can add anything to the end of a list, including another list.

>>> outer = [] >>> outer.append([1, 2]) >>> outer.append([3, 4]) >>> outer.append([5])

outer -> [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5]]

[5] list?How to obtain a reference to the list [5] in outer?

A: What index is it at within outer? 2

So access that list as outer[2]

>>> outer [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5]] >>> outer[2] [5]

nums = outer[2]?The expression outer[2] is a reference to the [5] list.

>>> outer = [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5]] >>> nums = outer[2] >>> >>> nums [5]

The expression outer[2] is a reference to the nested list [5]. The line nums = outer[2] sets the nums variable to point to the nested list. We will very often set a variable in this way, pointing to the nested structure, before doing operations on it.

6 on the [5]?The variable nums is pointing to the nested list [5]. Call nums.append(6) to append, changing the nested list. Looking at the original outer list, we see its contents are changed too. This shows that the nums variable really was pointing to the list nested inside of the outer list.

>>> nums.append(6) >>> nums [5, 6] >>> outer [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6]] >>> >>> # Could access list as outer[2] also: >>> outer[2].append(7) >>> outer [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6, 7]] >>>

The code in this problem builds on the basic outer/nums example above.

> add_99()

add_99(outer): Given a list "outer" which contains lists of numbers. Add 99 to the end of each list of numbers. Return the outer list.

The nest1 section on the server has introductory problems with nested structures.

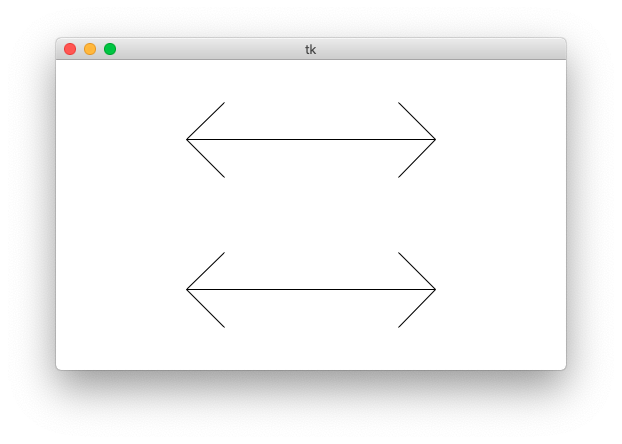

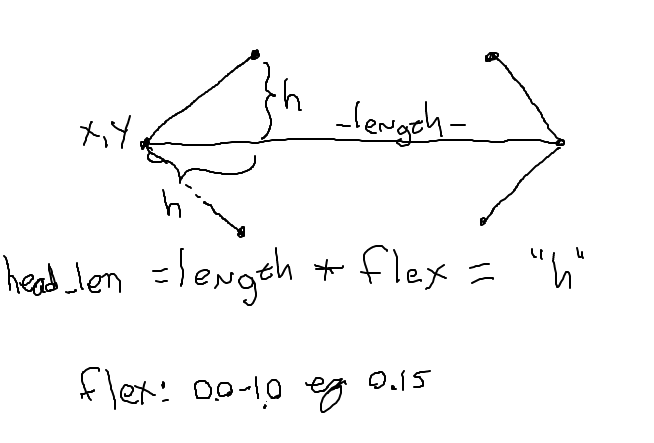

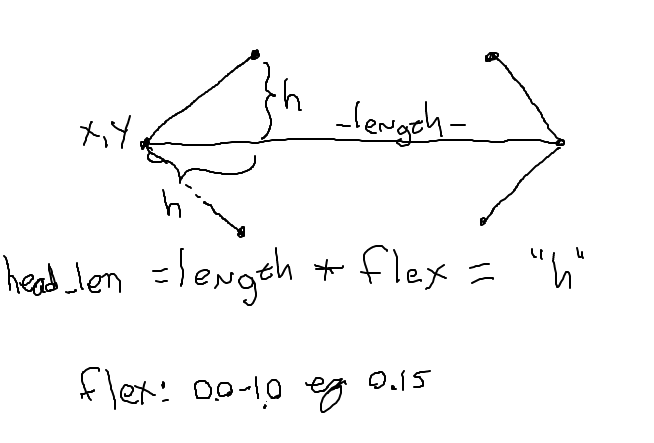

Download the flex-arrow.zip to work this fun little drawing example.

Recall: floating point values passed into draw_line() etc. work fine.

Ultimately we want to produce this output:

The "flex" parameter is 0..1.0: the fraction of the arrow's length used for the arrow heads. The arms of the arrow will go at a 45-degree angle away from the horizontal.

Specify flex on the command line so you can see how it works. Close the window to exit the program. You can also specify larger canvas sizes.

$ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.25 $ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.15 $ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.1 1200 600

Look at the draw_arrow() function. It is given x,y of the left endpoint of the arrow and the horizontal length of the arrow in pixels. The "flex" number is between 0 .. 1.0, giving the head_len - the horizontal extent of the arrow head - called "h" in the diagram. Main() calls draw_arrow() twice, drawing two arrows in the window.

This starter code the first half of the drawing done.

def draw_arrow(canvas, x, y, length, flex):

"""

Draw a horizontal line with arrow heads at both ends.

It's left endpoint at x,y, extending for length pixels.

"flex" is 0.0 .. 1.0, the fraction of length that the

arrow heads should extend horizontally.

"""

# Compute where the line ends, draw it

x_right = x + length - 1

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x_right, y)

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines, up and down from left endpoint

head_len = flex * length

# what goes here?

With head_len computed - what the two lines to draw the left arrow head? This is a nice visual algorithmic problem.

Code to draw left arrow head:

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines, up and down from left endpoint

head_len = flex * length

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x + head_len, y - head_len) # up

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x + head_len, y + head_len) # down

Here is the diagram again.

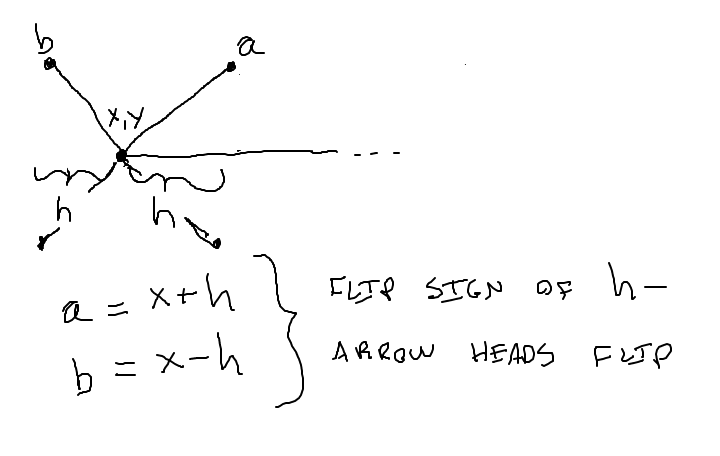

Add the code to draw the head on the right endpoint of the arrow. The head_len variable "h" in the drawing. This is a solid, CS106A applied-math exercise. In the function, the variable x_right is the x coordinate of the right endpoint of the line:x_right = x + length - 1

When that code is working, this should draw both arrows (or use the flex-arrow-solution.py):

$ python3 flex-arrow.py -arrows 0.1 1200 600

def draw_arrow(canvas, x, y, length, flex):

"""

Draw a horizontal line with arrow heads at both ends.

It's left endpoint at x,y, extending for length pixels.

"flex" is 0.0 .. 1.0, the fraction of length that the arrow

heads should extend horizontally.

"""

# Compute where the line ends, draw it

x_right = x + length - 1

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x_right, y)

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines, up and down from left endpoint

head_len = flex * length

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x + head_len, y - head_len) # up

canvas.draw_line(x, y, x + head_len, y + head_len) # down

# Draw 2 arrowhead lines from the right endpoint

# your code here

pass

canvas.draw_line(x_right, y, x_right - head_len, y - head_len)

canvas.draw_line(x_right, y, x_right - head_len, y + head_len)

Now we're going to show you something a little beyond the regular CS106A level, and it's a teeny bit mind warping.

Run the code with -trick like this, see what you get.

$ python3 flex-arrow.py -trick 0.1 1000 600

Note: one more thing today