Today: comprehensions, matplotlib intro

For more details, see the Python Guide Comprehensions section

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums] [1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36] >>> >>> [n * -1 for n in nums] [-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6]

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n + 10 for n in nums] [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] >>> [abs(n - 3) for n in nums] [2, 1, 0, 1, 2, 3] >>> [str(n) + '!!' for n in nums] ['1!!', '2!!', '3!!', '4!!', '5!!', '6!!']

We'll have more comprehensions exercises later. For now, we'll use them in a particular pattern for matplotlib.

Matplotlib is an extremely capable and popular Python module for producing visualizations of data. Install it with "-m pip" like this:

$ python3 -m pip install matplotlib

Matplotlib is super popular with researches and media for generating visualizations. There are many books and websites just about matplotlib. Matplotlib has a dizzying number of features. We will just scratch the surface here, so you get a feel for what's there, and can become more expert with it after CS106A if you like.

See see matplotlib.org and here is a popular tutorial (with tons of ads!): Matplotlib Tutorial

For this lecture example, we'll just use the few matplotlib features shown below, and later CS106A matplotlib work will use these same features.

Download to get started

mystery-data.zip which contains real data from the 2020 election. There's a lot of real data in here we can graph.

The file "mystery.py" is complete - we'll just play with it to experiment with matplotlib, and it is working example matplotlib code.

Data source: there's a nicely organized 2020 data set - graphics at the New York Times and other things you've seen are built from this data. It's also huge and complicated! The California and Texas data sets below are from this url.

The file ca-2020-election.csv looks like this: (you can click on it from within Pycharm to see it). There are more than 70,000 lines of data in here, with data for each voting precinct in California.

COUNTY,FIPS,RGPREC_KEY,ELECTION,TYPE,RGPREC,TOTREG_R,DEM,REP,AIP,PAF,MSC,LIB,NLP,GRN... 25,06049,0604902001,g20,V,02001,96,22,41,1,0,1,2,0,0,0,29,40,56,3,0,2,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0... 25,06049,0604904001,g20,V,04001,111,25,61,6,0,0,1,0,0,0,18,58,53,0,2,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,2,0,0... 25,06049,0604906001,g20,V,06001,365,101,184,16,2,0,2,0,4,0,56,166,199,5,10,2,1,5,4,3,1,0,0,.. ..

read_ca()How to parse this? No problem! Use: (1) for line in f, (2) line.split(',')

The function read_ca() parses the above text, computing a dict with one key for each county, and its value is the total votes in that county.

Run like this to see the dict computed by read_ca():

$ python3 mystery.py -ca ca-2020-election.csv

{'Modoc': 4349, 'Madera': 53889, 'Napa': 72700, 'Sonoma': 268569, 'Merced': 90482, 'Kern': 298938, 'San Joaquin': 281988, 'San Benito': 28724, 'Stanislaus': 211971, 'Ventura': 427164, 'Santa Cruz': 146024, ...

$

Say we want to produce graphics like this - bar chart for 3 counties, showing vote total per county.

At top of file, have the following import. This form of import sets up plt as a shorthand for matplotlib.pyplot

This is a standard, idiomatic shorthand used in most examples, so we're using it too.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

The function plot_ca1() builds the above plot with these steps.

First make the blank figure. One unit of size here is about 0.5 inch, so this is kind of 4 inches by 2 inches.

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

x_vals, y_valsWe have the votes dict, like this - key is county, value is votes in that county.

votes = {'Modoc': 4349, 'Madera': 53889, 'Napa': 72700, 'Sonoma': 268569, ... }

Compute the x_vals - the values going across the x-axis as a list. In this case, this is just a list of the 3 counties.

Compute y_vals - the vote total for each of the counties, in the same order as x_vals. Get the vote totals out of the dict, like this:

x_vals = ['Santa Cruz', 'Santa Clara', 'San Mateo']

y_vals = [votes['Santa Cruz'],

votes['Santa Clara'],

votes['San Mateo']]

# y_vals ends up as:

# [146024, 857609, 377876]

With x_vals, y_vals ready, call plt.bar() to make the bar chart. Set the color we want, add some titling and show it.

plt.bar(x_vals, y_vals, color='green')

plt.title('Votes Per County')

plt.show()

plot_ca1()Here is the code run with the -ca1 flag. Computes the counts dict as above, then has some basic matplotlib calls to put the data on screen. You will need to be able to write code like this to make graphs.

def plot_ca1(filename):

"""Plot 3 counties - basic matplotlib"""

votes = read_ca(filename)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4)) # each unit is about 0.5 inch

x_vals = ['Santa Cruz', 'Santa Clara', 'San Mateo']

y_vals = [votes['Santa Cruz'],

votes['Santa Clara'],

votes['San Mateo']]

# y_vals ends up as:

# [146024, 857609, 377876]

plt.bar(x_vals, y_vals, color='green')

plt.title('Votes Per County')

# plt.xlabel('County') # could have more titling

# plt.ylabel('Votes')

plt.show()

You can run with -ca1 on the command line which runs the above code to make that chart. This is the sort of code you will need later. Use the tab key to autocomplete the "ca-20..." filename.

$ python3 mystery.py -ca1 ca-2020-election.csv

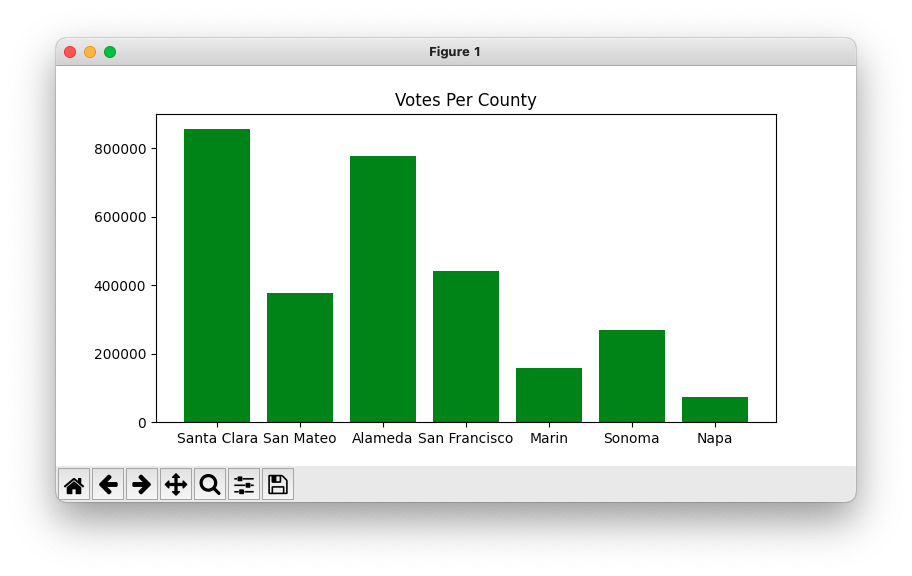

This version plots 7 bay area counties, run with the -ca2 flag on the same data file.

$ python3 mystery.py -ca2 ca-2020-election.csv

We don't want to have to manually type in the code to look up the value for each of the 7 counties.

Instead, the code below a comprehension to compute each y value - look at the y_vals = .. line. It uses a comprehension: for each county in x_vals, look up its value in the counts dict. Your code can use the simpler -ca1 technique above, but this use of the comprehension does the work very nicely.

def plot_ca2(filename):

"""Plot more ca counties, using comprehension"""

votes = read_ca(filename)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

# Expand to 7 bay-area counties

x_vals = ['Santa Clara', 'San Mateo',

'Alameda', 'San Francisco',

'Marin', 'Sonoma', 'Napa']

# Instead of typing each county again,

# comprehension pulls each county name

# out of the x_vals list - nice!

y_vals = [votes[county] for county in x_vals]

# y_vals ends up as:

# [857609, 377876, 777781, 442345, 156801, 268569, 72700]

plt.bar(x_vals, y_vals, color='green')

plt.title('Votes Per County')

plt.show()

The function first_digits() takes in a list of numbers, computes a dict of how often each first digit appears, used in the matplotlib code below. The function output looks like this - here saying that the digit 4 appears 7 times, the digit 5 appears 3 times, and so on.

first_digits(nums) ->

{4: 7, 5: 3, 7: 5, 2: 14, 9: 5, 1: 15, 8: 2, 6: 4, 3: 3}

Here is the code to draw 9 bars, for the digits 1, 2, 3, .. 9.

def plot_ca3(filename):

"""Plot first digits of all ca counties"""

votes = read_ca(filename)

nums = votes.values()

counts = first_digits(nums)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

x_vals = ['1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9']

y_vals = [counts[int(x)] for x in x_vals]

plt.bar(x_vals, y_vals, color='green')

plt.title('CA First Digits')

plt.show()

$ python3 mystery.py -ca3 ca-2020-election.csv

That does not look random or uniform. What is going on here? Why are 1 and 2 so much more prevalent? Maybe just random noise? Maybe signs of a conspiracy tampering with election data?

$ python3 mystery.py -tx tx-2020-election.csv

Hmmm again. This conspiracy is widespread!

Quote: The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not "Eureka!" (I found it!) but "That’s funny ..." - Isaac Asimov

Look at file potato-production.csv - 10,000 rows of potato production data in tons, like this

Afghanistan,AFG,1961,130000 Afghanistan,AFG,1962,115000 Afghanistan,AFG,1963,122000 Afghanistan,AFG,1964,129000 Afghanistan,AFG,1965,132000 ...

Have read_potato() function to read in the text file as before. Graph the digits of the values of this data set.

$ python3 mystery.py -potato potato-production.csv

Hmm. Looks just like the Texas data. This conspiracy is truly everywhere!