Today: loose ends: comprehension-if, truthy logic, floating point, open-source

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums] [1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36]

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n for n in nums if n > 3] [4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums if n > 3] [16, 25, 36]

These are all 1-liner solutions with comprehensions. We'll just do 1 or 2 of these.

Syntax reminder - e.g. make a list of nums doubled where n > 3

[2 * n for n in nums if n > 3]

Section on server: Comprehensions

> diff21

> first_up

> up_only (has if)

> even_ten (has if)

Comprehensions are easier to write than map(), so you can use them instead. Why did we learn map() then? Because map() is the ideal way to see how lambda works. At this point, you can use comprehensions instead of map, (and exam problems will give full credit to either form, your choice).

Programmers can get into Comprehension Fever - trying to write your whole program as nested comprehensions. Probably 1-line is the sweet spot.

Using regular functions, loops, variables etc. for longer phrases is fine.

Say we want to print a string if it is non-empty, this code works fine and you can write it this way, but there is a shorter way to do it shown below.

if len(s) > 0:

print(s)

The if and while are a little more flexible than we have shown thus far. They use the "truthy" system to distinguish True/False.

You never need to use this in CS106A, just mentioning it in case you see it in the future.

For more detail see "truthy" section in the if-chapter Python If - Truthy

Truthy logic says that "empty" values count as False. The following values, such the empty-string and the number 0 all count as False in an if-test:

# Count as False:

''

0

0.0

None

[]

{}

Any other value counts as True. Anything that is not one of the above False values:

# Count as True:

6

3.14

'Hello'

[1, 2]

{1: 'b'}

With truthy-logic, you can use a string or list or whatever as an if-test directly. This makes it easy to test, for example, for an empty string like the following. Testing for "empty" data is such a common case, truthy logic is a shorthand for it. For CS106A, you don't ever need to use this shorthand, but it's there if you want to use it. Also, many other computer languages also use this truthy system, so we don't want you to be too surprised when you see it.

# pre-truthy way:

if len(s) > 0:

print(s)

# truthy equivalent:

if s:

print(s)

> no_zero

The pylibs.py example file begins..

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Stanford CS106A Pylibs Example

Nick Parlante

"""

import sys

import random

...lots of code...

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

#!/usr/bin/env python3There are not huge differences between Python version-2 and version-3. You could easily write Python-2 code if you needed to, but Python-3 is strongly preferred for all new work. That said, many orgs may have old python-2 programs laying around, and it's easiest if they just use them and don't update or edit them. The first line #!/usr/bin/env python3 is a de-facto way of marking which version the file is for.

if __name__ Thing?What is this if __name__ test at the bottom of the file. Basically, every Python file has this at the bottom.

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Say you run a program like this:

$ python3 wordcount.py poem.txt

In that case, the if __main__ thing will be True. What does it do? It calls the main() function.

So if the program is run from the command line, call its main() function. That is the behavior we want, and it is what the above "if" does.

If the "if" were no there, running the program from the command line would not run its main() function.

What is the other way to load a python file? There is some other python code, and that code imports the python module.

# In some other Python file # and it imports wordcount ... import wordcount

In this more unusual case, the above "if" will be False. Loading a module does not run its main(), which is the behavior we want. Loading a module means I want to call its functions myself, not that I want its main() to start parsing the command line and doing its own thing.

You do not need to remember all those details. Just remember this: have that if-statement at the bottom of your file as a couple boilerplate lines. It calls the main() function when this file is run on the command line.

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

== vs. is== For ComparisonsUse == to compare two things, as we have done all quarter.

isThere is another comparison called is. This checks if two variables refer to the exact same object in memory.

You can go an entire lifetime and never need to use is operator in code - it just does not compute something that code typically needs to know. You should default to using == to compare values.

isHere is a demo of is, but you do not need this for CS106A.

>>> a = [1, 2, 3] >>> b = a >>> a is b # "is" True case True >>> c = [1, 2, 3] # c looks like a >>> a is c # "is" False case False >>> a is not c # "is not" variant True >>> >>> a == c # == returns True True >>>

is None RuleThe one time you need to use is is for PEP8 conformance. PEP8 says to use is for the values None, True, False, but really None is the one that comes up all the time.

So for PEP8, it's preferable to use is instead of ==, like below. The reasons for this are a bit obscure, but it's simplest to just follow PEP8.

if x == None: # Works, but not PEP8

print('nothing')

if x is None: # PEP8 this way

print('nothing')

So you should use is for comparison to None. Do not use is for anything else. We will never mark off CS106A code that uses == here (which in fact will work perfectly), but for PEP8 you can write it with is.

# int 3 100 -2 # float, has a "." 3.14 -26.2 6.022e23

>>> 0.1 0.1 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 0.2 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 # this is why we can't have nice things 0.30000000000000004 >>> >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.4 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.5 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.6 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.7 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.7999999999999999 # here the garbage is negative

Another example with 3.14

>>> 3.14 * 3 9.42 >>> 3.14 * 4 12.56 >>> 3.14 * 5 15.700000000000001 # d'oh

Conclusion: float math is slightly wrong

The short answer, is that with a fixed number of bytes to store a floating point number in memory, there are some unavoidable problems where numbers have these garbage digits on the far right. It is similar to the impossibility of writing number 1/3 precisely as a decimal number — 0.3333 is close, but falls a little short.

>>> a = 3.14 * 5 >>> b = 3.14 * 6 - 3.14 >>> a == b # Observe == not working right False >>> b 15.7 >>> a 15.700000000000001

>>> abs(a - b) < 0.00001 True >>> >>> import math >>> math.isclose(a, b) True

>>> # Int arithmetic is exact >>> a = 6 >>> b = 24 >>> >>> a * 5 30 >>> a * 5 - 6 24 >>> a * 5 - 6 == b True

Bitcoin wallets use this int strategy - the amount of bitcoin in a wallet is measured in "satoshis". One satoshi is one 100-millionth of 1 bitcoin. Each balance is tracked as an int number of satoshis, e.g. an account with 0.25 Bitcoins actually has 25,000,000 satoshis. Using ints in this way, the addition and subtraction to move bitcoin (satoshis) from one account to another comes out exactly correct.

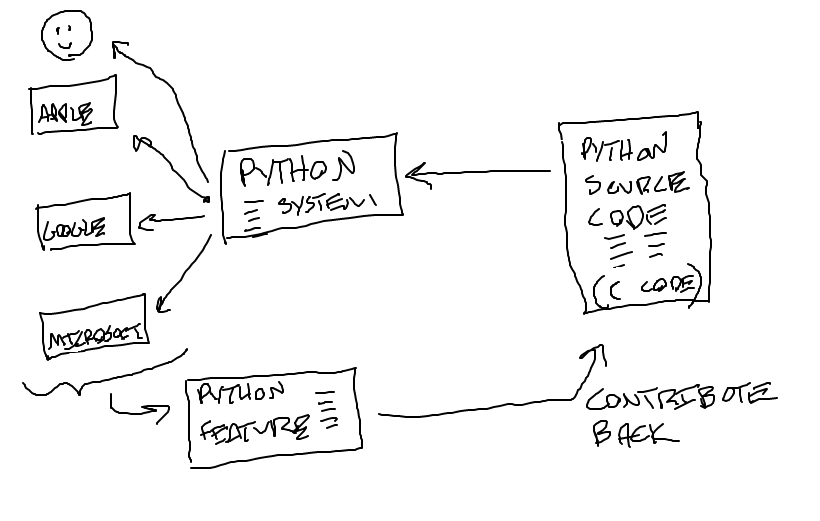

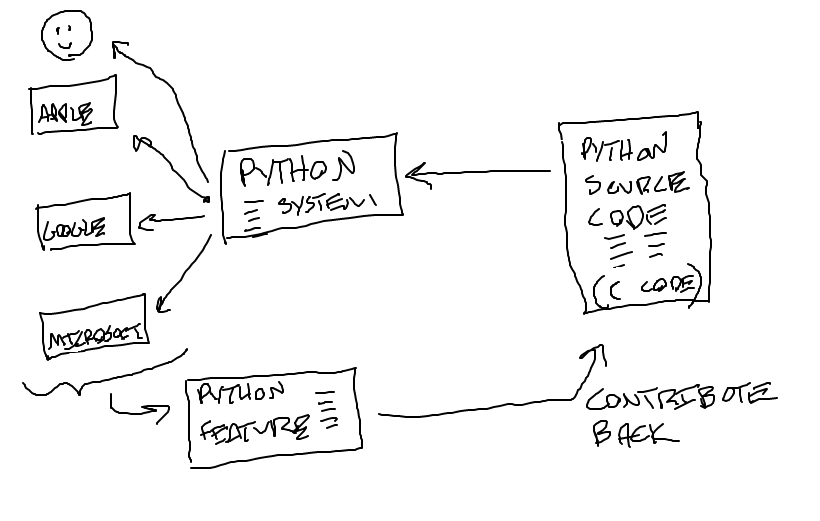

You have noticed that Python works well on your machine, and yet it's free. How does that work? Python is a great example of "open source" software.

Much of the internet is based on open standards - TCP/IP, HTML, JPEG - and open source software: Python (language), Linux (operating system), R (statistics system).

Let's look at Python

This open/free/shared model of technology is surprising and does not look like other markets. It is an incredibly successful model.