Today: function-call, decomposition bottom-up, top-down, delegation power, style-1

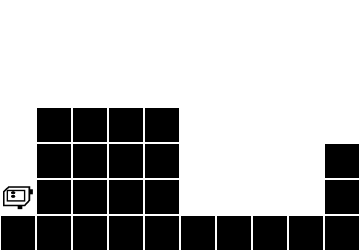

Here's a problem we'll use to talk about making a drawing.

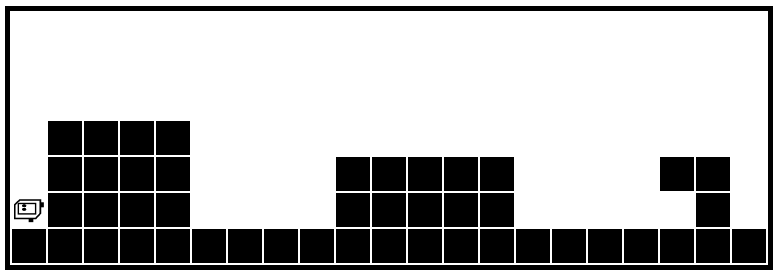

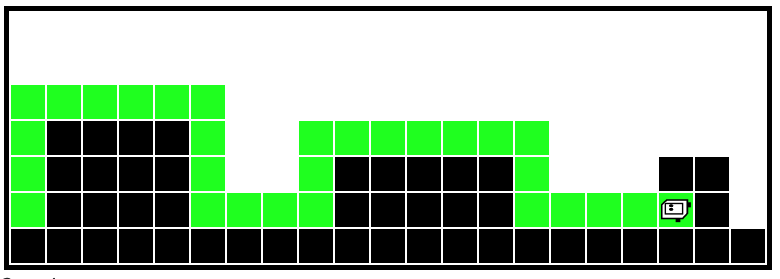

Problem: Bit moves forward until hole appears below. Then bit goes down the hole until a little niche appears on bits left side. Move bit into the niche.

> go-niche

I'll walk though how I use a drawing to work out the code. This is how you can work the homework problems too, especially if whatever you typed in first is not working and you cannot figure out why.

I think a lot of Stanford students feel like - I've gotten pretty far doing stuff in my head! But this work can be very detailed. Kind of "fiddly". The amount of detail is going to grow, so doing it in your head will not always work.

Don't watch the animation, clicking Run again and again. The animation is not generally well suited to debugging. With Bit, you can debug with the steps slider, dragging it to show a key moment when things go wrong.

The drawing is frozen, not moving. It can be fairly simple. Use the drawing to take your time with the details, work out the right test is for line 6 or whatever.

The phrase "detail oriented" is kind of running joke for code. People may be detail oriented, but with computer it's taken to the next level. This means we need to slow things down, work the details carefully.

Suppose you are staring at a blank screen and you don't know what line of code to type first. Making a little sketch of the input kind of gets your brain started to picking off parts of the problem.

Inevitably if you are stuck and come to office hours to get help (which is why we are here!). You will notice that the staffer will often end up making a little drawing to work out the details (or ask you to make the drawing).

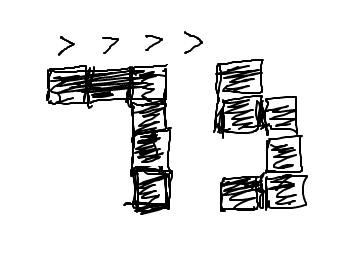

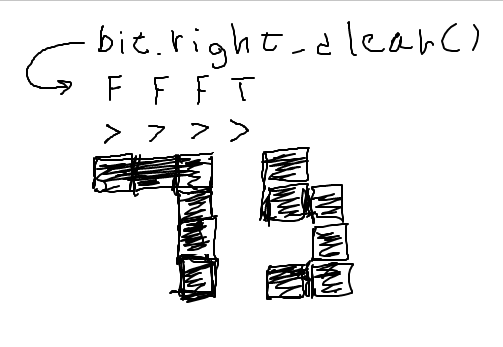

Here's the sort of drawing we might make to think about the start of this code. What is the while test to advance bit to the hole? This is the sort of drawing you could make to solve the homework problems.

bit.right_clear()What is the while-test to find the first hole? I think bit.right_clear() is a good first guess. We clearly want something to do with bit's right, and that's the one function we have there.

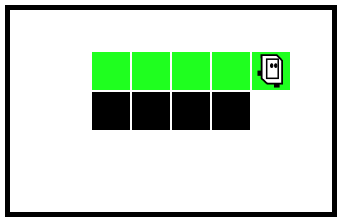

Put the boolean True/False values that function will return for each of bit's spots...

Recall: a black block is not clear. Therefore in the above drawing we have False when there's a block to bit's right and True otherwise.

That pattern of False/True there is not right. In fact, it's the exact opposite of what we want. We want True when bit should move and then a False at the last spot where bit should stop.

That's actually easy to fix. The not operator, to the left of a boolean value, inverts True/False. The correct test is while not bit.right_clear() - giving T T T F in the drawing, which advances bit to the hole perfectly.

We can click over to the problem and try that first loop. The rest of the problem you will need solve on your own.

> go-niche

This is not such an easy problem. Use a drawing to freeze the problem, work out the interplay between the details and the code. Then you are putting in the lines of code with intention, knowing what each does. Not putting in random lines and hitting Run in the hopes that maybe it will work.

Bit code cannot just do a move() any old time. The move needs to be preceded by a front_clear() check - in effect this is how bit looks where it is going. This is the issue with this next problem.

> double-move (while + two moves in loop)

The goal here is that bit paints the 2nd, 4th, etc. moved-to squares red, leaving the others blank. This can be solved with two moves and one paint inside the loop, but it's a little tricky.

The code below is a good first try, but it generates a move error for certain world widths. Why? The first move in the loop is safe, but the second will make an error if the world is even width. Run with Case-1 and Case-2 to see this.

def double_move(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.move()

bit.paint('red')

Usually you run your code one case at a time, using the Run All option as a final check that all the cases work. In this case, Run All reveals that some cases have a problem with the above code.

To figure out what is wrong with your code and fix, run a single case so the lines hilight as it runs. Use Run-All to find a case with a problem, but don't debug with it.

The problem is the second move - it is not guarded by a front_clear() check, so depending on the world width, it will try move through a wall. The first move in the loop does not have this problem - think about the while-test just before it.

So we don't know if the second move is safe or not. The solution is to put it in an if-statement that checks if the front is clear, only doing the move if front_clear is true:

def double_move(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move() # This move is fine

if bit.front_clear():

bit.move() # This move needs a check

bit.paint('red')

The Falling Water problem in the puzzle section also demonstrates this issue for practice.

Our big picture - program made up of functions

To "call" a function means to go run its code, and there are two ways it is done in Python. Which way a function is called is set by its author when the function is defined.

For "object oriented" code, which is how bit is built, the function call is the noun.verb form, e.g. bit.left(). Here "left" is the name of the function. Your code calls bit functions with this form now, and in future weeks we'll use many functions with the same noun.verb syntax...

bit.left() # turn bit s.lower() # compute lowercase of s lst.append(123) # append to list

def - Function Name and CodeLook at a def again to see what it does. Here's what def for a bit problem might look like...

def go_west(bit):

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

...

The def establishes that this function name, go_west, refers to these indented lines of code. the def does not run the code. It establishes that this name refers to this code. If another part of the program wants to refer to this function, it uses the name go_west.

The second type of function call in Python is deceptively simple. You just type the function's name with parenthesis after it. Here is what a line of code calling the above go_west function looks like:

...

go_west(bit)

...

The word "bit" goes in the parenthesis for now. We will explain that in detail later.

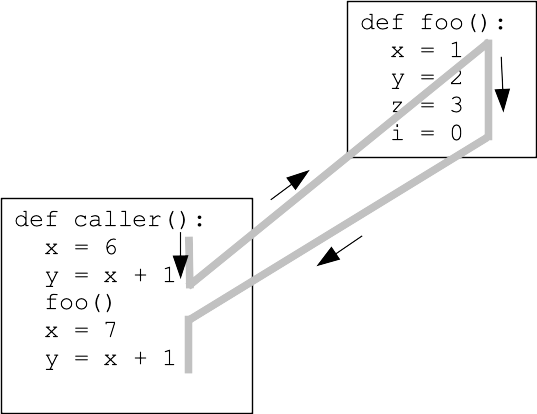

Calling a function prompts the computer to go run the code in that function, and then comes back to where it was. Say for example the computer is running in a "caller" function, and within there is a call to a foo() function - the computer goes to run the foo() code, then returns and continues in the caller function where it left off.

The computer is only running one function at a time.

High level - we have a program made of functions, each marked by a def and a name. Functions inside of the program will call each other, using their names. Python does not care what order the defs are in the program. Usually we put the simpler functions at the top, and the more complex ones below.

A "helper function" is function that solves a smaller, sub-problem. We build the helper function first, then later functions can call it to solve that sub-problem.

For our first examples, we'll work on the helper function first, then the function that calls it. This is the "bottom up" order. There's also a top-down example we'll do at the end where you write the helper last. These are both fine techniques.

This example demonstrates bit code combined with divide-and-conquer decomposition. We'll write a helper function to solve a sub-part of the problem.

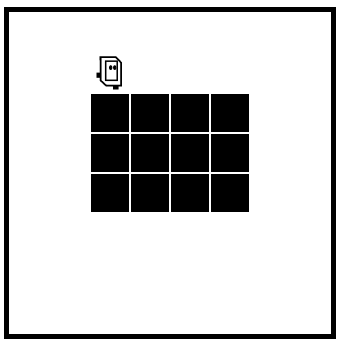

The whole program does this: bit starts at the upper left facing down. We want to fill the whole world with blue, like this

Program Before:

Program After:

fill_row_blue()First we'll decompose out a fill_row_blue() function that just does 1 row.

This is a "helper" function - solves a smaller sub-problem.

fill_row_blue() Before (pre)

fill_row_blue After (post):

We could have you write the code for this one, but we're providing it today to get to the next part.

Run the fill_row_blue() helper a few times (Case-1) to see what it does.

Now comes the magic step for today - calling the helper function.

fill_world_blue()To build a big program, don't write the whole thing and then try running it. Have a partially functional "milestone", get that working and debugged. Then work on a next milestone, and eventually the whole thing is done. We'll do this on every project, and it's the quickest way to get systems working.

As an experiment write code to just solve the first 2 rows, without a loop. This is a test "milestone", working out that some things work, but without solving the whole thing.

This can be done with 1 line of code. Think function-call.

Where is bit and with what facing after solving one row? How can you know what the bit state will be?

Put in a while loop, solve all the rows except the top one.

Put in one call to solve the top row, then a loop solves all the lower rows.

fill_world_blue() Solution

def fill_world_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename) # provided

fill_row_blue(bit)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

fill_row_blue(bit)

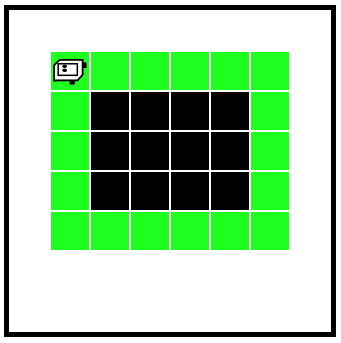

Bit starts next to a block of solid squares (these are not "clear" for moving). Bit goes around the 4 sides clockwise, painting everything green.

cover_square() Before (pre):

cover_square() After (post):

cover_side()Code for this is provided.

cover_side() Before: on top of first square, facing direction to go

cover_side() After - move until clear to the right, painting every square green

cover_side(bit) specification: Move bit forward until the right side is clear. Color every square green.

Run this code with case-1, to see what it does. (code provided)

cover_square()cover_square(bit) specification: Bit begins atop the upper left corner, facing right. Paint all 4 sides green. End one square to the left of the original position, facing up.

Add code to paint the top and right sides. Key ideas:

> Hurdles

Before

After

def solve_hurdles(filename):

"""

Solve the sequence of hurdles.

Start facing north at the first hurdle.

Finish facing north at the end.

(provided)

"""

while bit.front_clear():

solve_1_hurdle(bit)

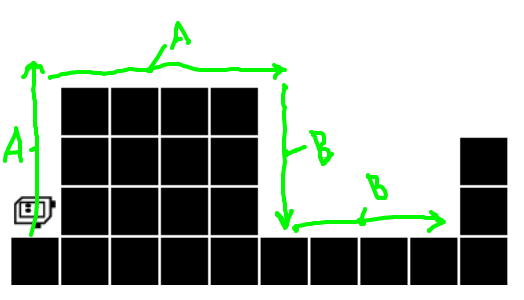

solve_1_hurdle()Want a helper function to solve one hurdle. If we had this, solve_hurdles() would be easy. Just doing one hurdle is not so intimidating. Divide and conquer!

What helper functions would be useful here? Make observation about the 4 moves that make up a hurdle.

Here is a sketch, working out that there are two sub-problem types

Imagine that the helpers go_wall_right() (A) and go_until_blocked() will exist. See if you can write code for solve_1_hurdle(), which is the most interesting function. You cannot run it until the helpers exist (next section).

solve_1_hurdle() Solution

def solve_1_hurdle(bit):

"""

Solve one hurdle, painting all squares green.

Start facing up at the hurdle's left edge.

End facing up at the start of the next hurdle.

"""

go_wall_right(bit)

bit.right()

bit.move()

go_wall_right(bit)

bit.right()

go_until_blocked(bit)

bit.left()

go_until_blocked(bit)

bit.left()

Now write the helpers for the A/B sub-problems. Here we see the importance of the pre/post to mesh the functions together. (For lecture demo, may just use prepared versions of these.)

def go_wall_right(bit):

"""

Move bit forward so long as there

is a wall to the right. Paint

all squares green. Leave bit with the

original facing.

"""

bit.paint('green')

while not bit.right_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

def go_until_blocked(bit):

"""

Move bit forward until blocked.

Painting all squares green.

Leave bit with the original facing.

"""

bit.paint('green')

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

With the helpers written, set solve_hurdles() to the code below, testing one hurdle but not the loop:

def solve_hurdles(filename):

"""

Solve the sequence of hurdles.

Start facing up at the left edge of a hurdle.

Finish facing up at the end.

(provided)

"""

bit = Bit(filename)

solve_1_hurdle(bit)

# Un-comment the loop when the helpers

# are done

# while bit.front_clear():

# solve_1_hurdle(bit)

When it can solve one hurdle, change it to the loop form to solve the whole thing:

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

solve_1_hurdle(bit)

Try running it on a few worlds. Switch to a small font so you can see all the code at once, watch the run jump around. Go, Bit go!

Think about writing that line where you call a helper

...

go_until_blocked(bit)

...

You can try the above lecture examples yourself. Use the "Reset Code" button to set it back to the start state.

There's also more problems on the experimental server for practice, Holes and Beloved:

> Holes

> Beloved

Some other points to clean up, if we have time.

There is a convention to put the smallest, helper functions first in a file. The larger functions that call them down below. This is just a habit; Python code will work with the functions in any order. Placing the helpers first does have a kind of logic — looking at solve_1_hurdle(), the functions it uses are defined above it, not after.

At the top of each function is a description of what the function does within triple-quote marks - we'll start writing these from now on. This is a Python convention known as "Pydoc" for each function. The description is essentially a summary of the pre/post in words, see the """ section in here:

def go_wall_right(bit):

"""

Move bit forward so long as there

is a wall to the right. Paint

all squares green. Leave bit with the

original facing.

"""

bit.paint('green')

while not bit.right_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

Previously we had separate testing for each helper which is ideal, and we will do that again in CS106A. In this case, we just run the whole thing and see if it works without the benefit of helper tests.

CS106A doe not just teach coding. It has always taught how to write clean code with good style. Your section leader will talk with you about the correctness of code, but also pointers for good style.

All the code we show you will follow PEP8, so just picking up the style tactic that way is the easiest.

See our Python Guide Style section. We'll pick out a few things today (for hw1), re-visit it for the rest later.