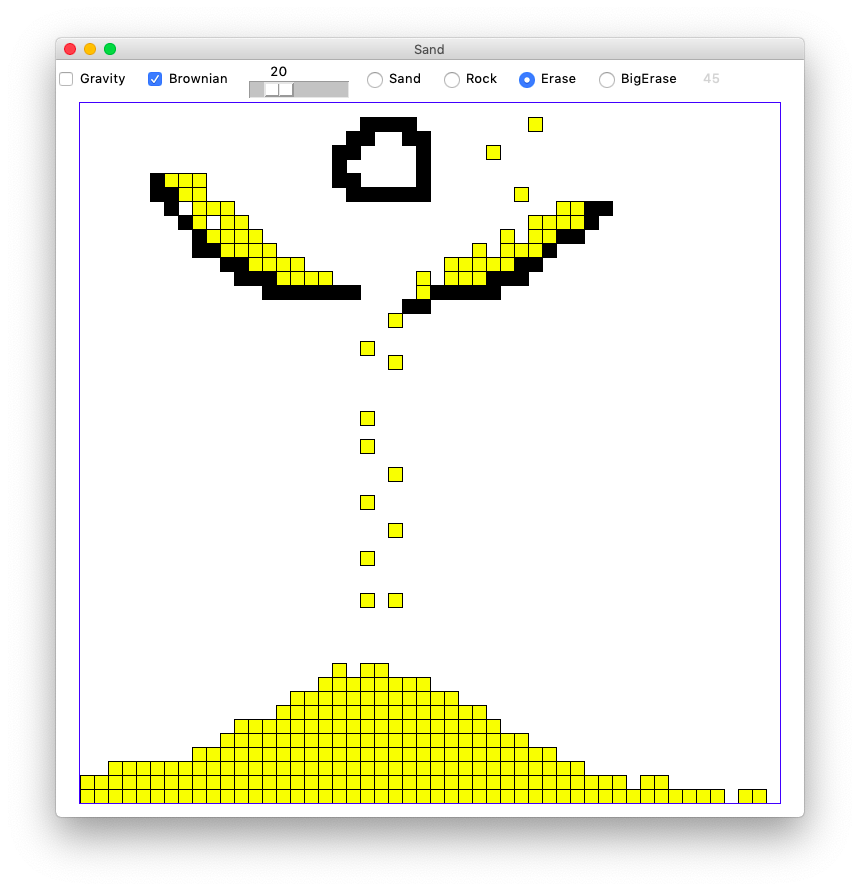

For this project you will write 2-d algorithmic code to implement a kind of 2-d world of sand. What my kids have described as the world's worst version of Minecraft. When it's working, it's kind of fun to play and watch in its low-key way.

The starter code handles setting up the GUI window, and handling the controls and drawing. All the logic that makes the world work will be built by you.

Homework 3 is due Wed Oct 18th at 11:55 pm. To get started, download sand.zip.

We will use the simple CS106A Grid utility class to store the 2-d data. See Grid Reference

Using the Grid looks like this

grid = Grid(3, 2) # make 3 by 2 grid, initially all None grid.set(0, 0, 'hi') # set a value at 0,0 val = grid.get(0, 0) # get a value out at 0,0 if grid.in_bounds(4, 5): # is 4,5 in bounds? ...

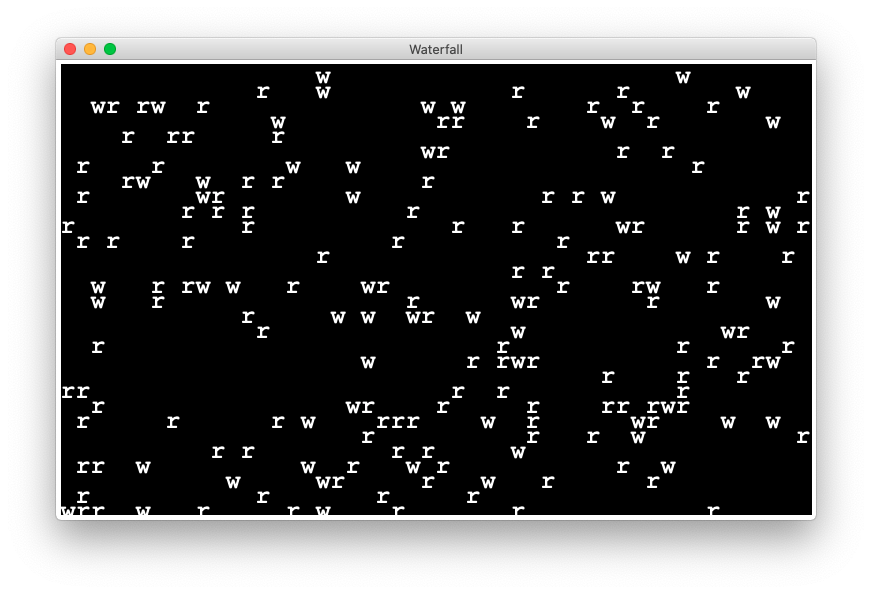

We'll start with the waterfall problem as a warmup. Look at the file waterfall.py - there are two function for you to write.

In the waterfall grid every square is either rock 'r', water 'w', or empty None. Every turn, every water moves. The only question is, which way will the water move, or will it disappear from the world.

We'll decompose the problem into two functions — (a) is_move_ok() checks boolean True/False if a destination square is open for a move, and (b) move_water() looks at a specific water and moves it.

def is_move_ok(grid, x_to, y_to):

"""

Given a grid and possibly out-of-bounds x_to, y_to

return True if that destination is ok, False otherwise.

...

"""

The is_move_ok() helper function checks if a particular x_to,y_to is a valid destination for water to move with the following checks:

1. If x_to,y_to is not in-bounds, the move is not valid, and nothing else needs to be checked.

2. If the x_to,y_to square is not empty, the move is not valid.

3. Otherwise, the move is valid.

This function does not require much code and does not need any loops. There are several ways a move might be invalid. Therefore, one approach uses a series of if-statements to recognize and return False for each form of invalid move, with a final return True as the last line. If the move gets past all the if-statements, then it must be valid.

We provide a set of Doctests in the starter code. Look them over, but you do not need to add any. Most of the Doctests use this grid as their input:

Use the Doctests to get this helper function working perfectly before moving on to the next step. Doctest pro-tip: when you have run a Doctest once, you can re-run it by clicking the green "play" button at the left-edge of the window. Running a Doctest again and again is the common pattern as you work on the functions like this, so you want to have a quick way to do it.

def move_water(grid, x, y):

"""

There is water at the given x,y.

Move the water to one of the 3 squares below,

or erase it, as described in the handout.

Return the grid when done.

(tests provided, code TBD)

>>> grid = Grid.build([['w', 'w', 'w'], ['r', None, 'w']])

>>> move_water(grid, 1, 0) # down ok

[['w', None, 'w'], ['r', 'w', 'w']]

...

"""

The move_water() function takes in the x,y of a square of water in the world and moves it in one of four ways and then returns the changed grid. There are no loops in this function. It works on a single x,y. Note: don't check if there is water at x,y just assume it is there, since that is the official precondition for move_water().

There are four possible moves for the water, checked in this order:

1. down If the square directly below the water is a valid move, move the water there and take no further actions. It's handy to use return grid to leave the function, avoiding the later steps. Move the water by setting its original square to None, and the new square to 'w'.

2. down-left If the square down-left is a valid move, move the water there and take no further actions.

3. down-right If the square down-right is a valid move, move the water there and take no further actions.

4. blocked If the above three moves are all invalid, the water disappears from the world.

In effect, the water tries down, down-left, down-right in that order, taking the first that works. If none of those work, the water disappears. In any case, return the changed grid.

CS106 mantra: use your helper function.

We provide basic Doctests which should be enough to get this working. Use the Doctests to perfect the code in this function before going on.

The Doctests use the same grid input as above:

For example, here is the first move_water() Doctest which tests a water which should go straight down:

>>> grid = Grid.build([['w', 'w', 'w'], ['r', None, 'w']])

>>> move_water(grid, 1, 0) # down ok

[['w', None, 'w'], ['r', 'w', 'w']]

It tries to move the middle water in the top row at (1, 0). The square immediately below that is empty, so the water should move from (1, 0) to (1, 1), resulting in the grid on the last line above.

Each Doctest needs to re-build the grid before calling move_water() .. why? This is necessary because each call to move_water() changes the grid. The later tests need a new grid, back in its initial state.

The "tall" Doctest checks that one run of move_water() moves the water only one square.

The move_water() function only does the work for a single x, y. A common question is — how is it that all the waters across the whole grid move? The following function is the answer.

The move_all_water() function is provided; please take a look at its code below so you see how the whole thing works. The function simply loops over the whole grid and calls your your move_water() function to move each water it comes across:

def move_all_water(grid):

"""

Move every water 'w' in the world

once by calling move_water() for each.

(provided)

"""

for y in reversed(range(grid.height)):

for x in range(grid.width):

if grid.get(x, y) == 'w':

move_water(grid, x, y)

return grid

With the Doctests for your two functions passing, run the waterfall program from the command line. It's a little entrancing. If you look carefully, you should see the three cases. Water dodging to the left around rocks is common, and in rare cases water going to the right when hitting the right of two or more rocks, and very rarely water disappearing when hitting the middle of three or more rocks. You may need to run a few times to get a random world that exhibits all the cases.

$ python3 waterfall.py

Of course watching the program run in realtime, it's impossible to see that it's behaving correctly all the time. We use the small, frozen-in-time Doctests to really see (and debug!) code like this.

You can also add width and height numbers at the end of the command line to run a different size waterfall. The default is 50 by 30. Run a nice big world and see how long you can entrance your roommate into watching it. See if they can figure out all the rules just by watching it.

$ python3 waterfall.py 80 50

Sand is a more complicated and interactive program. We'll use the same divide-and-conquer strategy divide the large program into many functions, and leverage Python's Doctests to test each function in isolation before moving on to the larger functions. You need to write four functions to make the whole thing work.

Every square in the Sand grid holds one of three things:

1. Sand represented by 's'

2. Rock represented by 'r'

3. Empty represented by None

In the sand world, each turn a sand 's' can move in one of five directions or stay where it is. Unlike waterfall, the sand does not disappear from the world.

The code for do_move() is provided. It's only two lines long. The """Pydoc""" defines what this function needs to do: move a sand from x_from,y_from to x_to,y_to, and return the changed grid to the caller. The function assumes that the move is legal (different code checks that). Two Doctests are provided.

def do_move(grid, x_from, y_from, x_to, y_to):

"""

Given grid and x_from,y_from with a sand,

and x_to,y_to. Move the sand to x_to,y_to

and return the resulting grid.

Assume that this is a legal move: all coordinates are in

bounds, and x_to,y_to is empty.

(i.e. a different function checks that this is a

legal move before do_move() is called)

(provided code)

>>> grid = Grid.build([['r', 's', 's'], [None, None, None]])

>>> do_move(grid, 1, 0, 1, 1)

[['r', None, 's'], [None, 's', None]]

>>>

>>> grid = Grid.build([['r', 's', 's'], [None, None, None]])

>>> do_move(grid, 2, 0, 2, 1)

[['r', 's', None], [None, None, 's']]

"""

The code for do_move() is short, but it is good example of using Doctests to spell out test cases. Run the Doctests and they should pass.

The is_move_ok() function is given a prospective x_from,y_from and an x_to,y_to for one of the 5 possible moves. It returns True if the move is ok, or False otherwise. Note: waterfall was so simple, it only need to the "to" coordinates, but sand needs both from and to.

The grid is not changed by this operation. Much of the complexity in this whole program is in this function, so we will give it a thorough testing.

Here is the Pydoc for the is_move_ok() function.

def is_move_ok(grid, x_from, y_from, x_to, y_to):

"""

Given grid and x_from,y_from and destination x_to,y_to

for one of the five possible moves. Assume x_from,y_from

is in bounds and contains sand. Is moving to x_to,y_to ok?

Return True if the move is ok, or False otherwise.

Ok move: destination is in bounds, empty, not violating corner rule.

"""

We'll call x_to,y_to the "destination" of the move. The destination will be one of the five possible moves for the sand: left, right, down, down-left, and down-right. Here are the rules for an ok move:

If the destination is out of bounds of the grid (OOB), the move is not ok.

Three Doctests for this rule are provided. These tests build a 1 row by 1 col grid, checking that a few out-of-bounds moves return False.

>>> # Provided out-of-bounds tests

>>> # Make a 1 by 1 grid with an 's' in it to check in-bounds cases

>>> grid = Grid.build([['s']])

>>> is_move_ok(grid, 0, 0, -1, 0) # left blocked

False

>>> is_move_ok(grid, 0, 0, 0, 1) # down blocked

False

>>> is_move_ok(grid, 0, 0, 1, 1) # down-right blocked

False

Your code: add 2 more tests for OOB.

If the destination square is not empty, the move is not ok.

In the above picture, the left move is ok, but the right move is blocked by a rock and is not ok. Sand there would also block the move; the logic should detect a non-empty square.

Of the five possible moves, this rule only applies to the diagonal down-left and down-right moves. For a down-left or down-right move, if the "corner" square above the destination square is not empty, the move is not ok.

Consider the down-left and down-right moves of the 's' here, with the diagonal moves shown in black and the others in gray:

The down-left move of the sand is not ok because of the corner rule, but down-right is ok. A sand in the place of the rock would also block the down-left move. The straight-left move is blocked since the square is not empty. The straight right move is ok. The corner rule applies to diagonal down-left or down-right moves, but not the other three moves.

After the OOB tests, the is_move_ok() starter code makes a 3 by 2 world, and includes one test showing that the left move from 1,0 is ok. Add at least 4 more tests, trying each of the other four directions: right, down, down-left, and down-right.

>>> # 3 by 2 grid, try various moves from 1,0

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 's', 'r'], [None, None, None]])

>>> is_move_ok(grid, 1, 0, 0, 0) # left ok

True

You should have at least one test of the empty and corner rules, and your tests should have a mixture of True and False results.

The tests do not need to be comprehensive. You want an average looking mixture of cases. The beauty of Doctests is that, in practice, just a few tests will expose most bugs.

Here is a typical sort of drawing you might make to think through the cases as you work on this code. Say you are thinking about moving the sand in the top row at 1,0. Each arrow corresponds to a different x_to,y_to passed in to is_move_ok(), with the correct True or False result depending on the contents of the grid.

With the tests describing the many cases done, write the code for the is_move_ok() function. No loops are needed in this function. Note that the grid has a grid.in_bounds(x, y) function that returns True if a particular x,y is in bounds or not.

There are many reasonable ways to structure this code. Obviously the one requirement is that the code returns the correct answer for all cases. Our solution has a single return True at the bottom of the function, and a series of if ... return False detecting the various ways the move may be bad. There are many ways a move can fail, so we have a series of if-statements to check for each of them in turn. A move has to get past all the checks before we know it's ok.

Use the Doctests as you work out the code. Sometimes a test fails because the function is wrong. Other times, upon review, you realize that your test is wrong, not spelling out the correct grid state. This is a normal, if tricky, sorting out of your code and your tests which is common on real projects.

At this time, it's fine to use == and != in comparisons like this if x != None. You may ignore warnings PyCharm gives you about that line. We'll refine that style rule later in the quarter.

Consider an x,y in the grid. This function implements one "gravity" move for that x,y as follows. In our gravity algorithm, the moves are handled in a specific order:

1. If there is not a sand 's' at x,y, do nothing, the move is over.

2. down: if the sand can move down, do it, this ends the move.

3. down-left: otherwise if the sand can move down left, do it, this ends the move.

4. down-right: otherwise if the sand can move down right, do it, this ends the move.

In all cases, return the grid when the function is done. Use your helper functions to do the work. This function should not contain any loops. We provide a pretty thorough set of Doctests for this function, but of course you still need to write the code to actually solve the problem. You can add more tests, but it's not required.

A test may fail here because of a bug in your do_gravity() code, or because the run here exposes a previously undiscovered bug in your helper function. That's normal. If the bug is in the helper, you might want to go back to the helper and add a test to get that code right, coming back here once the helper is sorted out.

def do_gravity(grid, x, y):

"""

Given grid and a in-bounds x,y. If there is a sand at that x,y.

Try to make one move, trying them in this order:

move down, move down-left, move down-right.

Return the grid in all cases.

(tests provided, code TBD)

>>> # not sand

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 's', None], [None, None, None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 0, 0)

[[None, 's', None], [None, None, None]]

>>>

>>> # down

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 's', None], [None, None, None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 0)

[[None, None, None], [None, 's', None]]

>>>

>>> # bottom blocked

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 's', None], ['r', 'r', 'r']])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 0)

[[None, 's', None], ['r', 'r', 'r']]

>>>

>>> # rock-below down-left

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 's', None], [None, 'r', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 0)

[[None, None, None], ['s', 'r', None]]

>>>

>>> # sand-below down-right

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, 's', None], ['s', 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 0)

[[None, None, None], ['s', 's', 's']]

>>>

>>> # sand corner: down-right

>>> grid = Grid.build([['s', 's', None], [None, 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 0)

[['s', None, None], [None, 's', 's']]

>>>

>>> # at bottom already

>>> grid = Grid.build([[None, None, None], [None, 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 1)

[[None, None, None], [None, 's', None]]

>>>

>>> # width 5 with 4 s - each s something different happens

>>> grid = Grid.build([['s', 's', None, 's', 's'], ['s', 's', None, 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 0, 0)

[['s', 's', None, 's', 's'], ['s', 's', None, 's', None]]

>>> grid = Grid.build([['s', 's', None, 's', 's'], ['s', 's', None, 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 1, 0)

[['s', None, None, 's', 's'], ['s', 's', 's', 's', None]]

>>> grid = Grid.build([['s', 's', None, 's', 's'], ['s', 's', None, 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 3, 0)

[['s', 's', None, None, 's'], ['s', 's', 's', 's', None]]

>>> grid = Grid.build([['s', 's', None, 's', 's'], ['s', 's', None, 's', None]])

>>> do_gravity(grid, 4, 0)

[['s', 's', None, 's', None], ['s', 's', None, 's', 's']]

"""

For the moment, ignore the "brownian" parameter which is handled in a later step.

Write code and tests for a do_whole_grid() function which calls do_gravity() once for every x,y in the grid. This is the function that goes through all the x,y, calling your other functions. Return the grid when done. Write two tests, with at least one test featuring a 3x3 world with sand at the top row. In your test, pass 0 for the brownian parameter to do_whole_grid().

The standard y/x nested loops go through the coordinates top-down, and normally that's fine. However, in this case, it's important to reverse the y-direction, going bottom-up, i.e. visit the bottom row y = height-1 first, then y = height - 2, and so on with the top row y = 0 last. Suggestion: use the reversed() function.

What's wrong with regular top-down order? Suppose the loops went top-down, and at y=0, a sand moved from y=0 down to y=1 by gravity. Then when the loop got to y=1, that sand would get to move again. Going bottom-up avoids this problem.

Run your Doctests in do_whole_grid() to see that your code is plugged in and working correctly.

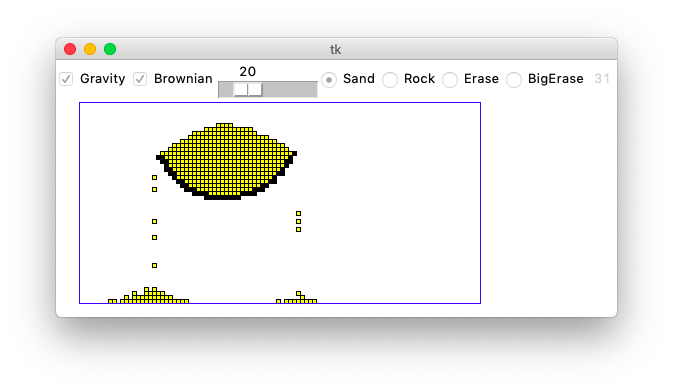

The do_whole_grid() does one "turn" of the world, calling do_gravity() a single time for each square. The provided GUI code calls this function again and again when the gravity checkmark is checked to make the game run.

With your functions tested, you can try running the whole program. Click the mouse button on a spot of the screen to scribble sand there. Gravity should work, but brownian is not done yet. Normally when a program runs the first time, there are many problems. But here we have leaned on decomposition and testing pretty hard, so there is a chance your code will work perfectly the first time. If your program works the first time, try to remember the moment. On projects where code is not so well tested, the first run of the program is often a mess. Having good tests changes the story.

Bring up the terminal and run the program like this (no command line arguments are required, on Windows its "py" or "python"):

$ python3 sand.py

Now for the last little bit of algorithm. Brownian motion is a real physical process, documented first by Robert Brown, who observed tiny pollen grains jiggling around on his microscope slide.

The "brownian" parameter is a number in the range 0..100 inclusive. When brownian is 20, that means there is a 20% chance that each sand will randomly try to move one square left or right each turn. The brownian number is taken in real time from the little slider at the top of the window, with the slider at the left meaning brownian=0 and at right meaning brownian=100. The Doctests are provided but you write the code (see below).

Here are the steps for the function do_brownian(grid, x, y, brownian):

1. Check if the square at x,y is sand. Proceed only if it is sand.

The Python function random.randrange(n) returns a random number uniformly distributed in the range 0..n-1. This is similar to the familiar range() function which is why "range" appears in the name of this function.

2. Create a random number in the range 0..99 with the following call.

num = random.randrange(100)

Proceed only if num < brownian. In this way, for example, if brownian is 50, we'll do the brownian move about 50% of the time.

3. Decide if the random move will be to the left or right. Set a "coin" variable like a coin flip with the following line. This lines sets coin to either 0 or 1:

coin = random.randrange(2)

4. If the coin is 0, try to move left. If the coin is 1, try to move right. Use your helper functions to check if the move is possible and do all the actual work (decomposition FTW). The coin indicates the direction for a single attempted move, and that's it. In this way the brownian motion is evenly balanced between left and right moves.

Testing an algorithm that behaves randomly is tricky. We have a little hack in the do_brownian() Doctest code that enables Docests there. The Doctest includes the following highly unusual line of code which we will further explain in week 9:

>>> # Hack: tamper with randrange() to always return 0

>>> # So we can write a test.

>>> # This only happens for the Doctest run, not in production.

>>> random.randrange = lambda n: 0

The line modifies the normal random.randrange() function so it returns 0 every time. Not exactly random! A couple tests are then written, knowing that the "random" value will always be zero when the Doctest runs. It's not a complete test, but it's better than nothing. When the code runs in production, the random numbers will behave normally.

Edit the loop body in do_whole_grid() so after do_gravity() for each x,y, it also calls do_brownian() for that x,y.

Try running the program with brownian switched on, which creates lively, less artificial look. Play around with the brownian slider to see your code in action.

You can provide 2 command line numbers to specify the number of squares wide and high for the grid. The default is 50 by 50 squares. So the following creates a grid 100 by 50

$ python3 sand.py 100 50

An optional third parameter specifies how many pixels wide each square should be. The default is 14. So this creates a 100 by 50 world with little 4 pixel squares, which changes the feel of the program.

$ python3 sand.py 100 50 4

The Sand program is pretty demanding on your computer. It runs a lot of computation without pause. You may notice the fans on your laptop spinning up. At the upper right of the window is a little gray number, which is the frames-per-second (fps) the program is achieving at that moment, like 31 or 52. The animation has a more fluid look with fps of, say, 50 or higher.

The more grid squares there are, and the more grains of sand there are, the slower the program runs. For each gravity round, your code needs to at least glance at every square and every grain of sand. By making the world large or by adding lots of sand, the fps of the game should go down. Play around with different grid and pixel sizes to try out the different esthetics.

Once you get that all working, congratulations. That's a real program with complex logic and some neat output.

When your code is working and has good cleaned up style, please turn in your waterfall.py and sand.py on paperless as usual.

This assignment is based on the "Falling Sand" assignment by Dave Feinberg at the Stanford Nifty Assignment archive. Nick Parlante re-built it in Python, adding in the emphasis on 2-d testing and decomposition, and created the waterfall as a warmup.