Today: accumulate patterns - counting and summing, int modulo, text files, standard output, print(), file-reading, crazycat example program

Look at double_char() and some similar functions to see a common pattern.

1. at the start: result = empty

2. In the loop, some form of: result += xxx

3. At the end: return result

Recognizing this pattern gives you have a head start solving similar problems.

A common problem in computer code is counting the number of times something happens within a data set. This is within the pattern, using count = 0 before the loop and count += 1 in the loop. Recall that the line count += 1 will increase the int stored in the variable by 1.

count = 0

loop:

if thing-to-count:

count += 1

return count

This string problem shows how to use += 1 to count the occurrences of something, in this case the number of 'e' in a string.

def count_e(s):

count = 0

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i] == 'e':

count += 1

return count

Suppose I want to add up a bunch of numbers. We can use the accumulate pattern here too. Set sum = 0 before the loop. Inside the loop, use sum += next_number to add each number to the sum. When the loop is done, the sum variable holds the answer.

sum = 0

loop:

sum += next_number

return sum

Say we want to rate an email about how long and how much shouting it has in it before we read - like scoring emails from your nutty relatives.

Example high-score email:

Hi Sarah, just relaxing in retirement. I CAN'T BELIEVE WHAT YOUR MOM IS UP TO!!!!!! WITH THAT NEW HAIRCUT!!!!!!!!!!!! AND WHY IS THANKSGIVING SO EARLY THIS YEAR!!!!!

Scoring for each char:

lowercase char -> 1 point

uppercase char -> 2 points

'!' char -> 10 points

Reminder, boolean string tests:

s.isalpha() s.isdigit() s.isspace() s.islower() s.isupper()

shout_score(s): Given a string s, we'll say the "shout" score is defined this way: each exclamation mark '!' is 10 points, each lowercase char is 1 point, and each uppercase char is 2 points. Return the total of all the points for the chars in s.

'Arg!!' -> 24 points 'A' -> 2 'r' -> 1 'g' -> 1 '!' -> 10 '!' -> 10

In the loop, use the sum pattern to compute the score for the string.

def shout_score(s):

score = 0

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i] == '!':

score += 10

elif s[i].islower():

score += 1

elif s[i].isupper():

score += 2

return score

Here using if/elif structure, since our intention is to pick out 1 of N tests. As a practical matter, it also works as a series of plain if. Since '!' and lowercase and uppercase chars are all exclusive from each other, only one if test will be true for each char.

Python code works on values, and each value has a "type" which determines how it behaves. Most often, what Python code will do follows your intuition. Here we'll look under the hood to see how Python tracks values and types.

Start off typing some + expressions in the interpreter. The results here are not surprising, but how does the + know what to do?

>>> 1 + 2 3 >>> >>> 'a' + 'b' 'ab' >>>

123 vs. '123'Q: What is the difference between these two?

123 vs. '123'

A: 123 is an int number, and '123' is a string length 3, made of 3 digit chars

int and strThese two values are different types. Every value in Python has a "type" which is its category of data. Each type in Python has an official name — name of the integer type is int and the string type is str

int str VariablesSuppose we set up these three variables

>>> a = 3 >>> b = 'hi' >>> c = '7'

Here is what memory looks like. Each variable points to its assigned value, as usual. In addition, each value in memory is tagged with its type - here int and str.

+ Operator orks - TypePython uses the type of a value to guide operations on that value. Look at the + operator in the expressions below. At the moment the + runs, it follows the arrow to see the values to use. On each value, in particular, it can see the type. In this case, when it see int, it does arithmetic and returns an int value. When it sees str, it does string concatenation and returns a str value.

For each variable, Python follows the arrow to get the value to use, and each value is tagged with its type. What is the result for the expressions like a + a below?

>>> a = 3 >>> b = 'hi' >>> c = '7' >>> >>> a + a 6 >>> b + b hihi >>> c + c 77 >>>

The + with int values does addition, but with str values it does string concatenation.

The type of '7' is str, so '7' + '7' is '77'

Normally we follow the convention that a variable named s to points to a string. This is a good convention, allowing people reading the code get the right impression of what the variable stores. We always follow this convention in our example code, so students naturally get the impression that it's some sort of rule. As if Python knows the value is a string because the variable name is s.

In fact, Python does not have a rule that a certain variable name must point to a certain type. To Python, the variable name is just a label of that variable used to identify it within the code. Python's attitude to the variable name is like: this is the name my human uses for this variable.

The type comes from the value at the end of the arrow, such as 7 (int) or 'Hello' (str).

Just to be difficult, here we've chose variable name that do not correspond to the types. What does Python do in this case?

>>> s = 7 >>> x = '9' >>> >>> s + s ??? >>> x + x ???

What are the ??? above?

int() str()'123' AdditionSay we have a number text = '123' typed by the user. We want to add 100 to it.

str + int - Error>>> text = '123' >>> text + 100 TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str >>>

The + works int/int or str/str but not like the above. Solution? Convert the str to int, then do the addition.

int(text) Then Add>>> text = '123' >>> int(text) + 100 223 >>>

The int() function converts str to int form, then we can do addition.

str(n) Then ConcatenateSimilarly, concatenation does not work with int. Use the str(n) function to convert int to str, then concatenate.

>>> # works the other way too >>> str(123) '123' >>> >>> # append int to str - error >>> 'score:' + 13 TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str >>> >>> # use str() convert int -> str >>> # then can concatenate >>> 'score:' + str(13) 'score:13' >>>

'12abc3' -> 6

Students try this one. It combines the accumulate pattern and str/int conversion.

Reminder, boolean string test: s.isdigit()

sum_digits(s): Given a string s. Consider the digit chars in s. Return the arithmetic sum of all those digits, so for example, '12abc3' returns 6. Return 0 if s does not contain any digits.

Here's the rote parts of sum_digits() you can start with. Work out the code inside the loop.

def sum_digits(s):

sum = 0

for i in range(len(s)):

# use s[i]

pass

return sum

def sum_digits(s):

sum = 0

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

# str '7' -> int 7

num = int(s[i])

sum += num

return sum

int — Division and ModLooking just briefly at two int arithmetic operators today - division and modulus - which go together.

/ always produces float>>> 7 / 2 3.5 >>> 8 / 2 4.0

Suppose we want to compute the middle index of a string, and then access the char at that index. The obvious way to do this is len(s) / 2 to get the midpoint index. Unfortunately that's a float, and it does not work within the square brackets:

>>> s = 'Python' >>> mid = len(s) / 2 >>> mid 3.0 >>> >>> s[mid] TypeError: string indices must be integers, not 'float' >>> >>> # Similarly with range() >>> range(7 / 2) TypeError: 'float' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

//The int division operator // rounds down to produce int. Use this when we want to divide and produce an int.

Python has a separate "int division" operator. It does division and discards any remainder, rounding the result down to the next integer.

>>> 6 // 2 3 >>> 7 // 2 3 >>> 8 // 2 4 >>> 94 // 10 9 >>> 102 // 4 25

Using int-division, can compute the string's midpoint index for a slice

>>> s 'Python' >>> mid = len(s) // 2 >>> mid 3 >>> s[mid] 'h'

'aabb' -> 'bbbbaaaa'

A problem using int-division.

right_left(s): We'll say the midpoint of a string is the len divided by 2, dividing the string into a left half before the midpoint and a right half starting at the midpoint. Given string s, return a new string made of 2 copies of right followed by 2 copies of left. So 'aabb' returns 'bbbbaaaa'.

% OperatorThe "modulo" operator % is essentially the remainder after int division. It's usually called the "mod" operator for short. So for example (57 % 10) yields 7 — int divide 57 by 10 and 7 is the leftover remainder. The mod operator makes the most sense with positive integers, so avoid negative numbers or floats with modulo.

Say we have positive ints a and n

a % n ...

1. Is the int emainder after dividing a by n

2. Always yields an int in the range 0..n-1 inclusive, e.g. mod by 10, is always an int 0..9

3 Returning 0 means the division came out evenly (i.e. 0 remainder)

4. Mod by 0 is an error, just like divide by 0

>>> 56 % 10 6 >>> 59 % 10 # biggest case 9 >>> 60 % 10 # 0 result -> divides evenly 0 >>> 54 % 5 4 >>> 55 % 5 0 >>> 56 % 5 1 >>> 56 % 0 ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero >>>

A simple use of mod is checking if an int is even or odd. Consider the result of n % 2. If the result is 0, then n is even, otherwise odd. It's common to use mod like this to, say, color every other row of a table green, white, green, white .. pattern. (See next example)

>>> 8 % 2 0 >>> 9 % 2 1 >>> 10 % 2 0 >>> 11 % 2 1 >>> 12 % 2 0

Produce that internet crazy capitalization like

tHeRe aRe nO MoRe bUgS

crazy_str(s): Given a string s, return a crazy looking version where the first char is lowercase, the second is uppercase, the third is lowercase, and so on. So 'Hello' returns 'hElLo'. Use the mod % operator to detect even/odd index numbers.

'Hello' -> 'hElLo'

index: 0 1 2 3 4

lower, upper, lower, upper, lower ...

even index: lower

odd index: upper

def crazy_str(s):

result = ''

for i in range(len(s)):

if i % 2 == 0: # even

result += s[i].lower()

else:

result += s[i].upper()

return result

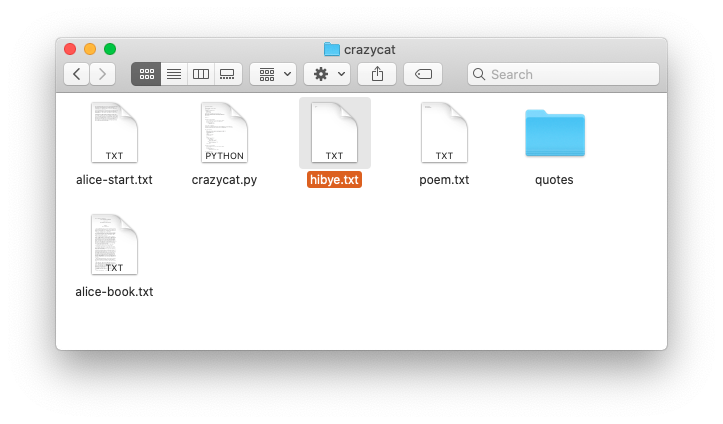

We'll use the crazycat example to demonstrate files, file-processing, printing, standard output, and functions.

We'll meet these later, but the CPU does the computation, RAM stores data when it's worked on, and storage holds files, data to work on later.

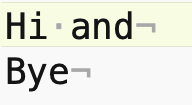

The file named "hibye.txt" is in the crazycat folder. What is a file? A file stores some data. The file has a name and holds a series of bytes representing, say, text, or an image. The data in the file remains intact, even if the computer is switched off. The file is said to be "non-volatile".

Text file: series of lines, each line a series of chars, each line marked by '\n' at end

The hibye.txt file has 2 lines, each line has a '\n' at the end.

The first line has a space, aka ' ', between the two words. Here is the complete contents:

Hi and bye

Here is what that file looks like in an editor that shows little

gray marks for the space and \n (like show-invisibles mode in word processor):

In Fact the contents of that file can be expressed as a Python string - see how the newline chars end each line:

'Hi and\nbye\n'

Use backslash \ to include special chars within a string literal. Note: different from the regular slash / on the ? key.

\n newline char \' single quote \" double quote \\ backlash char # Write the word: isn't s = 'isn\'t' # use \ s = "isn't" # use "

How many chars are in that file (each \n is one char)?

There are 11 chars. The latin alphabet A-Z chars like this take up 1 byte per char. Characters in other languages take 2 or 4 bytes per char. Use your operating system to get the information about the hibye.txt file. What size in bytes does your operating system report for this file?

So when you send a 50 char text message .. that's about 50 bytes sent on the network + some overhead. Text data like this uses very few bytes compared to sound or images or video.

In the old days, there were two chars to end a line. The \r "carriage return", would move the typing head back to the left edge. The \n "new line" would advance to the next line. So in old systems, e.g. DOS, the end of a line is marked by two chars next to each other \r\n. On Windows, you will see text files with this convention to this this day. Python code largely insulates your code from this detail - the for line in f form shown below will go through the lines, regardless of what line-ending they are encoded with.

Before reading the file, need some background.

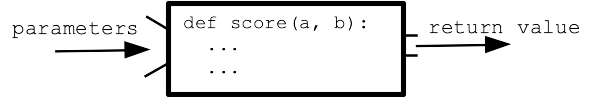

Q: How does data flow between the functions in your program?

A: Parameters and Return value

Parameters carry data from the caller code into a function when it is called. The return value of a function carries data back to the caller.

This is the key data flow in your program. It is 100% the basis of the Doctests. It is also the basis of the old black-box picture of a function. This is still true, despite what we see in the next section.

BUT .. there is an additional, parallel output area for a program, shared by all its functions.

There is a text area known as Standard Output associated with every run of a program. By default standard output is made of text, a series of text lines, just like a text file. Any function can append a line of text to standard out by calling the print() function, and conveniently that text will appear in the terminal window hosting that run of python code. the standard output area works in other computer languages too, and each language has its own form of the print() function.

Here we see the print() output from calling the main() function in this example:

See guide: print()

output -Try print() in the interpreter, see its output right there

>>> print('hello there')

hello there

>>> print('hello', 123, '!')

hello 123 !

>>> print(1, 2, 3)

1 2 3

Return and print() are both ways to get data out of a function, so they can be confused with each other. We will be careful when specifying a function to say that it should "return" a value (very common), or it should "print" something to standard output (rare). Return is the most common way to communicate data out of a function, but below are some print examples.

This example program is complete, showing some functions, Doctests, and file-reading.

See guide: Command line

See guide: File Read/Write

Open the crazycat project in PyCharm. Open a terminal in the crazycat directory (see the Command Line guide for more information running in the terminal). Terminal commands - work in both Mac and Windows. When you type command in the terminal, you are typing command directly to the operating system that runs your computer - Mac OS, or Windows, or Linux.

pwd - print out what directory we are in

ls - see list of filenames ("dir" on older Windows)

cat filename - see file contents ("type" on older Windows)

$ ls __pycache__ hibye.txt quote2.txt alice-book.txt poem.txt quote3.txt crazycat.py quote1.txt quote4.txt $ $ cat hibye.txt Hi and bye $ $ cat poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme $ $ cat quote1.txt Shut up, he explained. - Ring Lardner $

$ python3 crazycat.py poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme $ python3 crazycat.py hibye.txt Hi and bye $

Say the variable filename holds the name of a file as a string, like 'poem.txt'. The file 'poem.txt' is out in the file system with lines of text in it. Here is the standard code to read through the lines of the file:

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

# use line

...

1. The phrase - with open(filename) as f - opens a connection to that file and stores it in the variable f. Code that wants to read the data from the file works through f which is a sort of conduit to the file.

2. The phrase for line in f: accesses each line of the file, one line at a time, as detailed below.

Here is how the variables "f" and "line" access the lines of the file:

Detail: in reality, the chars for each line reside in the file, not in memory. The loop constructs a string in memory to represent each line on the fly. This can be done using little memory, since it only constructs one line at a time, even if the file is very large.

There are other less commonly used variations on the open function described in the guide. If the file read fails with a unicode error, the file may have an unexpected unicode encoding. The following variation lets you specify a different encoding, so you can try to find an encoding that matches the file: open(filename, encoding='utf-8'). The encoding "utf-8" is one widely used encoding shown as an example.

s.strip() FunctionThe string s.strip() function, removes whitespace chars like space and newline from the beginning and end of a string and returns the cleaned up string. Here we use it as an easy way to get rid of the newline.

>>> s = ' hello there\n' >>> s ' hello there\n' >>> s.strip() 'hello there'

line = line.strip()Each line string inside the the for line in f loop has the '\n' newline char at its end. Half the time, this newline char makes no difference to anything, and half the time it ends up getting in the way.

Therefore, we will make a habit of adding line = line.strip() in the loop which removes the '\n' char so we don't have to think about it.

line.strip()Here is the file read code with the line.strip() added to remove the '\n'. For CS106A, we will always write it this way, so we never see the '\n'.

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

line = line.strip()

# use line

If some CS106A problem asks you to read all the lines of a file, you could paste in the above.

Back to crazycat example - look at the code.

This command line we saw earlier calls the print_file_plain() function below, passing in the string 'poem.txt' as the filename.

$ python3 crazycat.py poem.txt Roses Are Red Violets Are Blue This Does Not Rhyme

Here is the print_file_plain() function that implements the "cat" feature - printing out the contents of a file. You can see the code is simply the standard file-reading code, and then for each line, it simply prints the line to standard output.

def print_file_plain(filename):

"""

Given a filename, read all its lines and print them out.

This shows our standard file-reading loop.

"""

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

line = line.strip()

print(line)

The main() function looks for '-crazy' option on the command line. We'll learn how to code that up soon. For now, just know that main() calls the print_file_crazy() function.

Here is command line to run with -crazy option

$ python3 crazycat.py -crazy poem.txt rOsEs aRe rEd vIoLeTs aRe bLuE tHiS DoEs nOt rHyMe

How does the program produce that output?

crazy_str(s) FunctionRecall the crazy_str(s) black-box function that takes in a string, and computes and returns a funny-capitalization version of it. This function is included in crazycat.py.

crazy_str('Hello') -> 'hElLo'

-crazy Code Plan1. Read each line of text from the file with the standard loop.

2. Call the crazy_str() function passing in each line, getting back the crazy version of that line.

3. Print the crazy version of the line.

The code is similar to print_file_plain() but passes each line through the crazy_str() function before printing. Think about the flow of data for each iteration of the loop - from the line variable, through crazy_str(), and printed to standard output.

def print_file_crazy(filename):

"""

Given a filename, read all its lines and print them out

in crazy form.

"""

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

line = line.strip()

line_crazy = crazy_str(line)

print(line_crazy)

1. Run on alice-book.txt - 3600 lines. The file for-loop rips through the data in a fraction of a second. You can get a feel for how your research project could use Python to tear through some giant text file of data.

python3 crazycat.py -crazy alice-book.txt

2. Shorten the print() in the loop to one line, as below. Describe the sequence of things that happens to each line:

print(crazy_str(line))

3. (very optional) Try removing the line = line.strip(). What happens to the output? What is happening: the line has a '\n' at its end. The print() function also adds a newline at the end of what it prints.

Try running this way, works on all operating systems:

$ python3 crazycat.py -crazy alice-book.txt > capture.txt

What does this do? Instead of printing to the terminal, it captures standard output to a file "capture.txt". Use "ls" and "cat" to look at the new file. This is a super handy way to use your programs. You run the program, experimenting and seeing the output directly. When you have a form you, like use > once to capture the output. Like the pros do it!