Today: parsing, while loop vs. for loop, parse words out of string patterns, boolean precedence

AnnounceL: exam monday eve, no lecture monday

Here's some fun looking data...

$GPGGA,005328.000,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,2,07,1.3,22.5,M,-25.7,M,2.0,0000*70 $GPGSA,M,3,09,23,07,16,30,03,27,,,,,,2.3,1.3,1.9*38 $GPRMC,005328.000,A,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,0.00,256.18,221217,,,D*78 $GPGGA,005329.000,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,2,07,1.3,22.5,M,-25.7,M,2.0,0000*71 $GPGSA,M,3,09,23,07,16,30,03,27,,,,,,2.3,1.3,1.9*38 $GPRMC,005329.000,A,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,0.00,256.18,221217,,,D*79 $GPGGA,005330.000,3726.1389,N,12210.2515,W,2,07,1.3,22.5,M,-25.7,M,3.0,0000*78 $GPGSA,M,3,09,23,07,16,30,03,27,,,,,,2.3,1.3,1.9*38 ...

for i/rangeThe for/i/range form is great for going through numbers which you know ahead of time - a common pattern in real programs. If you need to go through 0..n-1 - use for/i/range, that's exactly what it's for. For example, if we want to loop over 0..5, say to index into 'Python'

whileBut we also have the while loop. The "for" is suited for the case where you know the numbers ahead of time. The while is more flexible. The while can test on each iteration, stop at the right spot. Ultimately you need both forms, but here we will switch to using while.

It's possible to write the equivalent of for/i/range as a while loop instead. As a practical matter, you would not go through 0..n-1 thais way, but it does illustrate the while loop structure to go through a series o numbers.

Here is the while-equivalent to for i in range(n)

i = 0 # 1. init

while i < n: # 2. test

# use i

i += 1 # 3. update at loop-bottom

# (easy to forget this line)

> while_double() (in parse1 section)

double_char() written as a while. The for-loop is the better approach for this problem. Here just showing for/while equivalence.

def while_double(s):

result = ''

i = 0

while i < len(s):

result += s[i] + s[i]

i += 1

return result

With the for/range loop, you never get an infinite loop. But with the while loop, it's not so hard to get an infinite loop — say you forget the i += 1 step, or write the test incorrectly. The while loop is more powerful, and predictably, it has more risk of screwups, so we use it only for cases where the simple for/range is insufficient.

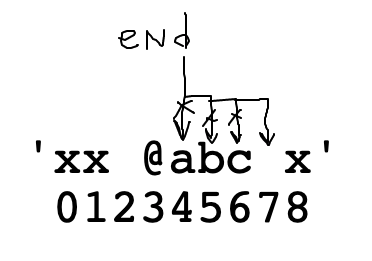

var += 1Start with end = 4. Advance to space char with end += 1 in loop

i In Bounds?Suppose the int i is indexing into a string, and I am changing it with i += 1 or i -= 1. What are the bounds for i remaining a valid index into the string?

i < length

If we are increasing an index variable i, then i < length is the easy test that i is a valid index; that it is not too big.

i >= 0

If we are decreasing i, then i >= 0 is the valid check, since 0 is the first index. Could equivalently write this as i > -1, but usually it's written as i >= 0.

Python detail: surprisingly s[-1] does not give an error in Python, it accesses the last char. For our algorithms though, we treat i >= 0 as the boundary.

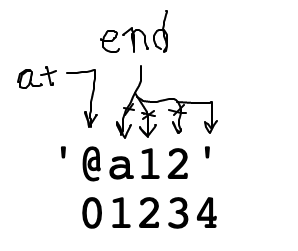

> at_word() (in parse1 section)

'xx @abcd xyz' -> 'abcd' 'x@ab^xyz' -> 'ab'

at_word(s): We'll say an at-word is an '@' followed by zero or more alphabetic chars. Find and return the alphabetic part of the first at-word in s, or the empty string if there is none. So 'xx @abc xyz' returns 'abc'.

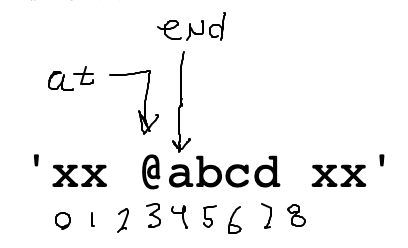

First use s.find() to locate the '@'. Then start end pointing to the right of the '@'.

Code to set this up:

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

end = at + 1

Use a while loop to advance end over the alphabetic chars. What is the test for this loop? Work it out on the drawing.

while ????

end += 1

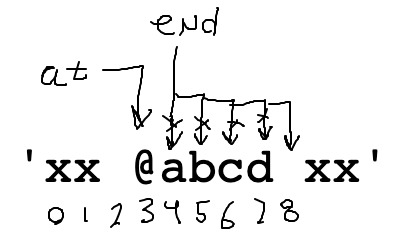

This loop is 90% correct to advance end:

# Advance end over alpha chars

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

Once we have at/end computed, pulling out the result word is just a slice.

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

Put those phrases together and it's an excellent first try, and it 90% works. Run it.

def at_word(s):

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

end = at + 1

# Advance end over alpha chars

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

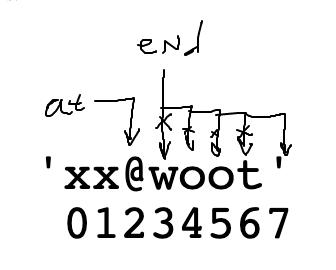

That code is pretty good, but there is actually a bug in the while-loop. It has to do with particular form of input case below, where the alphabetic chars go right up to the end of the string. Think about how the loop works when advancing "end" for the case below.

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

'xx@woot' 01234567

Problem: keep advancing "end" .. past the end of the string, eventually end is 7. Then the while-test s[end].isalpha() throws an error since index 7 is past the end of the string.

The loop above translates to: "advance end so long as s[end] is alphabetic"

To fix the bug, we modify the test to: "advance end so long as end is valid and s[end] alphabetic".

In other words, stop advancing if end reaches the end of the string.

Loop end bug:

end < len(s) Guard TestThis "guard" pattern will be a standard part of looping over something.

We cannot access s[end] when end is too big. Add a "guard" test end < len(s) before the s[end]. This stops the loop when end gets to 7. The slice then works as before. This code is correct.

def at_word(s):

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

# Advance end over alpha chars

end = at + 1

while end < len(s) and s[end].isalpha():

end += 1

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

The "and" evaluates left to right. As soon as it sees a False it stops. In this way the < len(s) guard checks that "end" is a valid number, before s[end] tries to use it. This a standard pattern: the index-is-valid guard is first, then "and", then s[end] that uses the index. We'll see more examples of this guard pattern.

s[at + 1:end]>>> s = 'Python' >>> len(s) 6 >>> s[2:5] 'tho' >>> s[2:6] 'thon' >>> s[2:46789] 'thon'

exclamation(s): We'll say an exclamation is zero or more alphabetic chars ending with a '!'. Find and return the first exclamation in s, or the empty string if there is none. So 'xx hi! xx' returns 'hi!'. (Like at_word, but right-to-left).

Set a variable start to the left of the exclamation mark. Move it left over the alphabetic chars.

Starter code

def exclamation(s):

exclaim = s.find('!')

if exclaim == -1:

return ''

# Your code here

start = ???

Will need a guard here, as the loop goes right-to-left. The leftmost valid index is 0, so that will figure in the guard test.

def exclamation(s):

exclaim = s.find('!')

if exclaim == -1:

return ''

# Your code here

# Move start left over alpha chars

# guard: start >= 0

start = exclaim - 1

while start >= 0 and s[start].isalpha():

start -= 1

# start is on the first *non* alpha

word = s[start + 1:exclaim + 1]

return word

See the guide for details Boolean Expression

The code below looks reasonable, but doesn't quite work right

def good_day(age, is_weekend, is_raining):

if not is_raining and age < 30 or is_weekend:

print('good day')

Because and is higher precedence than or as written above, the code above acts like the following (and evaluates before or):

if (not is_raining and age < 30) or is_weekend:

You can tell the above does not work right, because any time is_weekend is True, the whole thing is True, regardless of age or rain. This does not match the good-day definition above, which requires that it not be raining.

The solution we will spell out is not difficult.

Solution

def good_day(age, is_weekend, is_raining):

if not is_raining and (age < 30 or is_weekend):

print('good day')

(Got this far in lecture - exercise TBD)

> oh_no()

'xx @ab12 xyz' -> 'ab12'

at_word99(): Like at-word, but with digits added. We'll say an at-word is an '@' followed by zero or more alphabetic or digit chars. Find and return the alpha-digit part of the first at-word in s, or the empty string if there is none. So 'xx @ab12 xyz' returns 'ab12'.

We've reached a very realistic level of complexity for solving real problems.

Like before, but now a word is made of alpha or digit - many real problems will need this sort of code. This may be our most complicated line of code thus far in the quarter! Fortunately, it's a re-usable pattern for any of these "find end of xxx chars" problems.

The most difficult part is the "end" loop to locate where the word ends. What is the while test here? (Bring up at_word99() in other window to work it out). We want to use "or" to allow alpha or digit.

at = s.find('@')

end = at + 1

while ??????????:

end += 1

# 1. Still have the < guard

# 2. Use "or" to allow isalpha() or isdigit()

# 3. Need to add parens, since this has and+or

# combination

while end < len(s) and (s[end].isalpha() or s[end].isdigit()):

end += 1

def at_word99(s):

at = s.find('@')

if at == -1:

return ''

# Advance end over alpha or digit chars

# use "or" + parens

end = at + 1

while end < len(s) and (s[end].isalpha() or s[end].isdigit()):

end += 1

word = s[at + 1:end]

return word

If we have time, we'll look at these.

'xx www.foo.com xx' -> 'www.foo.com'

dotcomt2(s): We are looking for the name of an internet host within a string. Find the '.com' in s. Find the series of alphabetic chars or periods before the '.com' with a while loop and return the whole hostname, so 'xx www.foo.com xx' returns 'www.foo.com'. Return the empty string if there is no '.com'. This version has the added complexity of the periods.

Ideas: find the '.com', loop left-right to find the chars before it. Loop over both alphabetic and '.'

def dotcom2(s):

com = s.find('.com')

if com == -1:

return ''

# "or" logic - move leftwards over

# alphabetic or '.'

start = com - 1

while start >= 0 and (s[start].isalpha() or s[start] == '.'):

start -= 1

return s[start + 1:com + 4]

Below here optional

Command-return = run in exp server

Command-/ = comment, uncomment

Tab, Shift-tab = indent, unindent

Ctrl-k = delete line. Works in Gmail and in most browser forms. Super satisfying!

Normally each Python line of code is un-broken. BUT if you add parenthesis, Python allows the code to span multiple lines until the closing parenthesis. Indent the later lines an extra 4 spaces - in this way, they have a different indentation than the body of the while. There's also a preference to end each line with an operator like or .. to suggest that there's more on the later lines.

while (end < len(s) and

(s[end].isalpha() or

s[end].isdigit())):

end += 1

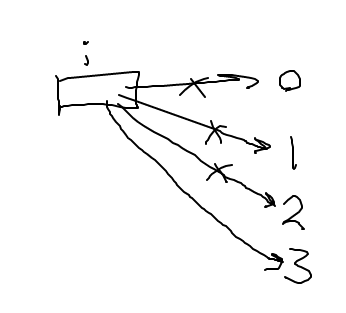

With the following code, it's clear that the assignment = sets the variable to point to a value.

x = 7

It's less obvious, but the for loop just sets a variable too, once for each iteration. The variable name is the word the programmer chooses right after the word "for", in this example the variable is i which is an idiomatic choice:

for i in range(4):

# use i

print(i)

0

1

2

3

The Sartre of Coding!

The variable name is just the label applied to the box that hold the pointer.

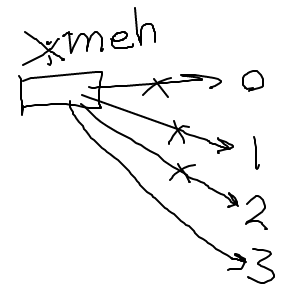

You might get the feeling in CS106A to this point: it will only work if the variable is named "i", but that's not true. We always name it "i" since that's the idiom programmers use for that context, so you cannot be blamed for thinking it was some Python rule.

We try to choose a sensible label to keep our own thoughts organized. However the computer does not care about the word used, so long as the word chosen is used consistently across lines. The variable name i is idiomatic for that sort of loop. But in reality we could use any variable name, and the code would work exactly the same. Say we name the variable meh instead .. same output. All that matters is that the variable on line 1 is the same as on line 2.

for meh in range(4):

print(meh)

0

1

2

3

This is a little disturbing. We do try to choose good and/or idiomatic variable names for our own sake. However, the computer does not notice or care about the actual word choice for our variables. The computer does not understand English here; it just recognizes that two words are the same and so must be the same variable.