Today: loose ends - comprehension-if, truthy logic, #! line, float flaws, future of AI

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums] [1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36]

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n for n in nums if n > 3] [4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums if n > 3] [16, 25, 36]

These are all 1-liner solutions with comprehensions.

Syntax reminder - e.g. make a list of nums doubled where n > 3

[2 * n for n in nums if n > 3]

Section on server: Comprehensions

> up_only (has if)

> even_ten (has if)

Comprehensions are easier to write than map(), so you can use them instead. Why did we learn map() then? Because map() is the ideal way to see how lambda works. At this point, you can use comprehensions instead of map, (and exam problems will give full credit to either form, your choice).

Programmers can get into Comprehension Fever - trying to write your whole program as nested comprehensions. Comprehensions are so dense, they can be unreadable if too long. Probably 1-line is the sweet spot for a comprehension.

Using regular functions, loops, variables etc. for longer phrases is fine.

The if and while are actually a little more flexible than we have shown thus far. They use the "truthy" system to distinguish True/False.

You never need to use this in CS106A, just mentioning it in case you see it in the future.

For more detail see "truthy" section in the if-chapter Python If - Truthy

FalseTruthy logic says that "empty" values count as False. The following values, such the empty-string and the number 0 all count as False in an if-test:

# All count as False:

None

''

0

0.0

[]

{}

TrueAny other value counts as True. Anything that is not one of the above False values:

# Count as True:

6

3.14

'Hello'

[1, 2]

{1: 'b'}

The bool() function takes

any value and returns a formal bool False/True value, so for any value, it reveals how Truthy logic will treat that value. You don't typically use bool() in production code. Here we're using it to see Python's internal logic.

>>> # "Empty" values count as False

>>> bool(None)

False

>>> bool('')

False

>>> bool(0)

False

>>> bool(0.0)

False

>>> bool([])

False

>>> # Anything else counts as True

>>> bool(6)

True

>>> bool('hi')

True

>>> bool([1, 2])

True

These are tricky / misleading. Can always try it in the interpreter.

>>> bool(7)

True

>>> bool('')

False

>>>

>>> bool(0)

False

>>>

>>> bool('hi')

True

>>>

>>> bool('False') # SAT Vibes

True

>>>

>>> bool(False)

False

>>>

>>>

With truthy-logic, you can use a string or list or whatever as an if-test directly. This makes it easy to test, for example, for an empty string like the following. Testing for "empty" data is such a common case, truthy logic is a shorthand for it. For CS106A, you don't ever need to use this shorthand, but it's there if you want to use it. Also, many other computer languages also use this truthy system, so we don't want you to be too surprised when you see it.

# Pre-truthy code:

if word != '':

print(word)

# Truthy equivalent:

if word:

print(word)

Truthy logic is just a shortcut test for the empty string or 0 or None. Those are pretty common things to test for, so the shortcut is handy. You do not need to use this shortcut in your writing, but you may see it in when reading code. Most computer languages use Truthy logic like this, not just Python.

> no_zero

There are lines of Python code we have glossed over. Today we will explain these.

Usual practice: to create a new Python file, copy an existing Python file you have laying around. In this way, you get the #!/usr/bin... and other bits of rote syntax mentioned here.

What is up with that very first line: #!..

#!/usr/bin/env python3 """ Stanford CS106A Pylibs Example ...

#!/usr/bin/env python3This first line specifies that the file is Python 2 code

#!/usr/bin/python ...

There are not huge differences between Python version-2 and version-3. You could easily write Python-2 code if you needed to, but Python-3 is strongly preferred for all new work. That said, many orgs may have old python-2 programs laying around, and it's easiest if they just use them and don't update or edit them. The first line #!/usr/bin/env python3 is a de-facto way of marking which version the file is for.

You do not need to remember all those details. Just remember this: have that if-statement at the bottom of your file as a couple boilerplate lines. It calls the main() function when this file is run on the command line.

...

... python file ..

...

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

When you run a program from the command line like this, Python loads the whole file, and then finally calls its main() function.

$ python3 pylibs.py

The if-statement shown above is the bit of code that calls main(). It's a historical quirk that Python does not simply call main() automatically, but it doesn't, so we have this if-statement at the bottom of the file.

Typically, when starting a new Python project, you copy a Python file you have laying around. In this way, you get the boilerplate #!/usr/bin.. line at the start, and this if-main line at the end of the file.

Say you run a program like this:

$ python3 wordcount.py poem.txt

In that case, the if __main__ expression will be True. What does it do? It calls the main() function. So if the python file is run from the command line, call its main() function. That is the behavior we want, and it is what the above "if" does.

What is the other way to load a python file? There is some other python code, and that code imports the python file.

# In some other Python file # and it imports wordcount ... import wordcount

In this more unusual case, the above "if" will be False. Loading a python file (module) does not run its main(). So the if-statement runs main() when the python file is itself run from the command line, but does not run main() when the file is imported by another file.

# int 3 100 -2 # float, has a "." 3.14 -26.2 6.022e23

Note: do not panic! We can work with this. But it is shocking.

What is happening here?

>>> 0.1 0.1 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 0.2 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 # this is why we can't have nice things 0.30000000000000004 >>> >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.4 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.5 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.6 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.7 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.7999999999999999 # here the garbage is negative

Another example with 3.14

>>> 3.14 * 3 9.42 >>> 3.14 * 4 12.56 >>> 3.14 * 5 15.700000000000001 # d'oh

Conclusion: float math is slightly wrong

The short answer, is that with a fixed number of bytes to store a floating point number in memory, there are some unavoidable problems where numbers have these garbage digits off to the right. It is similar to the impossibility of writing the number 1/3 precisely as a decimal number — 0.3333 is close, but falls a little short.

>>> a = 3.14 * 5 >>> b = 3.14 * 6 - 3.14 >>> a == b # Observe == not working right False >>> b 15.7 >>> a 15.700000000000001

>>> a = 3.14 * 5 >>> b = 3.14 * 6 - 3.14 >>> >>> import math >>> math.isclose(a, b) True >>> >>> abs(a - b) < 0.0001 True >>>

>>> # Int arithmetic is exact >>> # The two expressions are exactly equal, "precise" >>> 2 + 3 5 >>> 1 + 1 + 3 5 >>> >>> 2 + 3 == 1 + 1 + 3 True >>>

Doesn't seem like such a high bar .. and yet float does not give us this!

Bank balance example: Bank balances can be stored as int number of pennies. That way, adding and subtracting from one account to another comes out exactly right and balanced.

In fact, Bitcoin wallets use exactly this int strategy - the amount of bitcoin in a wallet is measured in "satoshis". One satoshi is one 100-millionth of 1 bitcoin. Each balance is tracked as an int number of satoshis, e.g. an account with 0.25 Bitcoins actually has 25,000,000 satoshis. Using ints in this way, the addition and subtraction to move bitcoin (satoshis) from one account to another comes out exactly correct. int is precise!

Say we start with the Gettysburg address:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

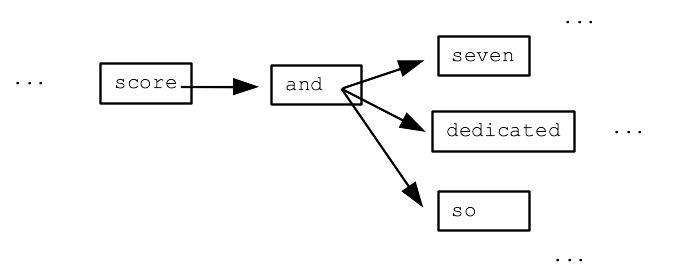

We'll build a "bigrams" dictionary with a key for every word in the text. (It's "bigrams" since we consider pairs of words, and the technique scales to looking at more than 2 words.) The value is a list of all the words that occur immediately after that word in the text. This is not a difficult dict to build with some Python code.

{

'Four': ['score'],

'score': ['and'],

'and': ['seven', 'dedicated', 'so', 'proper', 'dead,', 'that'],

'seven': ['years'],

...

}

The bigrams dict forms a sort of word/arrow model (aka a "Markov model), where each word has arrows leading to the words which might follow it.

We can write code to randomly chase through this bigrams model - output a word, then randomly select a "next" word, output that word, and keep going.

Here are 3 randomly generated texts using this simple bigrams Gettysburg model:

1. Four score and dedicated to the living, rather, to the great civil war, testing whether that all men are met on a great task remaining before us to dedicate a great battle-field of that we can not have come to add or any nation so nobly advanced.

2. Four score and seven years ago our poor power to dedicate -- we can never forget what we can not hallow -- and dead, who fought here to be dedicated to add or any nation so nobly advanced. It is for those who struggled here, have thus far so nobly advanced.

3. Four score and dedicated to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long endure. We are met on a portion of freedom -- that this nation, or any nation might live. It is for those who fought here to add or any nation might live. It is for us to be dedicated to dedicate a portion of devotion -- that nation might live.

1. It's kind of vaguely similar to the input. It's impressive considering that we just look at pairs of words and that's all.

2. However the output doesn't really make sense or have sense in it; it's just replaying fragments vaguely imitating the source text.

This simple bigrams model reflects a bit of how ChatGPT / LLM AI works.

Read in a huge source text, building a "model" that in some way summarizes or captures patterns in the original. It's not a copy of the original, but a sort of distillation.

The contents of the model reflects and depends on the source text it's built from.

The output is made by traversing and working through model (with a prompt).

The bigrams example shows the structure, but the real AI is, say, a million times deeper. If the bigrams example is the scale of a shoe, then the LLMs are the scale of a whole automobile.

So with this in mind, here are 4 points to keep in mind about AI..

The AI output sounds intelligent, but this is mostly a mirage. It is replaying human fragments with intelligence in them. This why the AI is not good at avoiding falsehoods.

We could say there is range of interpretations of the AI ranging from "intelligent" to "replay" explanations of what it's doing. There is certainly a lot of replay in the AI output.

BUT maybe intelligence is in there too? Maybe human behavior actually has a lot of replay in it?

The AI is mostly useful for putting out fragments that are common or similar to what it was trained on. It's shocking how good it is already at writing human text or bits of code. I assume it's because there was much human text and code in its inputs, and it's distilled well the important patterns in there.

It saves time, so no doubt it will become a standard practice to have AI speed up writing bits of text or code.

Currently AI written code is close, but most often has flaws too. A person who understands the lines of code needs to edit/fix it.

CS106A: we're learning the basics, so I don't mind asking you to write and understand the basic code phrases yourself. Perhaps in a later course, you will use this knowledge of the basics to fix and craft code snippets from an AI.

I expect the AI will make programming, say, 2x more productive. Like the AI solves rote pieces, but rarely solves the whole problem. Human insight is still very valuable.

I think you will still need human programmers in the process.

Say you are a book publisher.

You can feed the AI every book written in the last 50 years, ask it to write a new book in some genre.

The AI does just kind of a B+ job of it .. but it's super cheap. You can have sort of an infinite series of AI created books in maybe a person-specific genre, like "animals having adventures". This is also kind of violating the copyright of the original authors, though any one book is just a microscopic part of the model. Once the AI books are out there, it may be hard for the original authors to do much about it.

My prediction; we see AI created art, e.g. books, and the quality is kind of "B+". But the cost will be near zero and the available volume will be huge.

I tried to think of a bit of art that resonates very well for me (of course it will be a very different piece of art for each person, this one happens to be a Nick favorite).

Think of the scene from Harry Potter - where we see the tombstone

Here lies Dobby, a free elf.

I think that is a beautiful and deep moment in the book series, embedding a lot of emotion and it ties together a story arc that spans thousands of pages. (Editor note: what can we say about the maturity of Nick's literary taste? It is the CS department; let us not judge.]

So here is a question, suitable for the dinner table when conversation stalls: Will an AI every craft a story moment as rich as that?

My gut says no. However, when someone says a technology will never do something, often a few years later, the technology surprises and does it.

Aside: the Harry Potter audio books ready by Jim Dale are great IMHO. Pull them up if you have a long drive.

Aside 2: I wonder if that scene is less meaningful for people who have only seen the movies. I've read that most of the Dobby plot is left out of the movies and the CGI is maybe not great.