Today: error handling, dict output, wordcount.py example program, list functions, state-machine pattern

A small feature in Babynames has to do with error handling, so we'll talk about that here.

An "exception" in Python halts the program with an error message and notes the line number. You have seen these many, many times.

The last line of the error message describes the specific problem, and the "traceback" lines above give context about the series of function calls / line-numbers which lead to the error. Generally just look at the last couple lines to see the error and the line of code where it occurred. We can prompt an exception easily enough with some bad code in the interpreter

>>> s = 'Hello' >>> s[9] Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> IndexError: string index out of range >>>

The first and simplest rule for error conditions is this: when the program encounters a problem so the computation cannot continue, we want the program to stop running, "halt", and print some sort of error message describing the problem.

Many Python built in functions, such as a string access out of bounds, or the function open(filename), raise an exception with an error message when given bad data. The exception will halt the program with an appropriate exception for many common situations automatically, without the programmer adding any error handling code. You have seen this exception-halt behavior countless times as your code runs into problems.

What do you do if your code runs into a situation, say with its data, where the data is wrong and the code cannot continue?

We want to tap in to the exception infrastructure, and the simplest way to do it is: raise Exception('message'), which raises an exception to halt the program at that line, with the message string describing the problem.

You can try it in the interpreter to see the error print out.

>>> raise Exception('Something is wrong')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

Exception: Something is wrong

For example, suppose deep in some function, a parameter n is greater than 10, the computation cannot continue. In that case, the code could halt the program with an exception like this (docs):

# Raise exception if n is too big

if n > 10:

raise Exception('n should be less than 10')

...

Whoever is running the program can look at the error message to debug the situation. Say for example, they miss-typed a number on the command line, or mis-typed the name of a file wrong so the code halted with a FileNotFoundError.

Python has a taxonomy of different sorts of exceptions that code can raise, but the above raise Exception('msg') is the simplest and that's what we'll do for HW6.

Some older programming systems would not halt when the data was bad. In effort to be helpful, the code would stumble forward, pretending that the missing data was the empty string or whatever to see if that would work. This turned out to waste more time in the end, as it hid the underlying error. Imagine debugging that system, where input a is wrong, but the program grinds forward to fail with bad data b a few lines later. That's harder to debug, as the underlying issue is obscured. So the best practice is simply to halt with a real error message immediately when bad data is detected.

Thus far examples follow this pattern, looping over some input data, loading and organizing the data into a dict:

counts = {}

for s in strs:

...

counts[xxx] = yyy

...

What about getting data out of the dict?

Wordcount example below - show the full load-up and print-out lifecycle.

dict.keys()

>>> # Load up dict

>>> d = {}

>>> d['a'] = 'alpha'

>>> d['g'] = 'gamma'

>>> d['b'] = 'beta'

>>>

>>> # d.keys() - list-like "iterable" of keys,

>>> d.keys()

dict_keys(['a', 'g', 'b'])

>>>

>>> # Can loop over d.keys()

>>> for key in d.keys():

... print(key)

...

a

g

b

>>>

>>> # d.values() - not used as often

>>> d.values()

dict_values(['alpha', 'gamma', 'beta'])

for key in d.keys():Say we want to print the contents of a dict. Loop over d.keys() to see every key, look up the value for each key. This works fine and accesses all of the dict. The only problem is that the keys are in random order.

>>> d = {'a': 'alpha', 'g': 'gamma', 'b': 'beta'}

>>> for key in d.keys():

... print(key, '->', d[key])

...

a -> alpha

g -> gamma

b -> beta

sorted(lst)>>> nums = [5, 2, 7, 3, 1] >>> sorted(nums) [1, 2, 3, 5, 7] >>> >>> strs = ['banana', 'alpha', 'donut', 'carrot'] >>> sorted(strs) ['alpha', 'banana', 'carrot', 'donut']

sorted(d.keys())>>> d.keys() # random order - not pretty dict_keys(['a', 'g', 'b']) >>> >>> sorted(d.keys()) # sorted order - nice ['a', 'b', 'g'] >>> >>> for key in sorted(d.keys()): ... print(key, '->', d[key]) ... a -> alpha b -> beta g -> gamma

for key in d:

>>> d = {'a': 'alpha', 'g': 'gamma', 'b': 'beta'}

>>> for key in sorted(d):

... print(key)

...

a

b

g

list(xxx)The d.keys() is not exactly a list. You can loop over it and take len(), but square bracket [ ] does not work. If you have a list-like and need an actual list, you can form one with list() as below. Typically this is not needed for CS106A, as looping is good enough.

>>> # list-like: loop and len() work >>> d.keys() dict_keys(['a', 'g', 'b']) # list-like >>> len(d.keys()) 3 >>> >>> d.keys()[2] # [ ] no work TypeError: 'dict_keys' object is not subscriptable >>> >>> strs = list(d.keys()) # make real list >>> strs ['a', 'g', 'b'] # now [ ] works >>> strs[2] 'b' >>>

The wordcount program below reads in a text, separates out all the words, builds a count dict to count how often each word appears, and finally produces a report with all the words in alphabetical order, each with its count, this:

$ python3 wordcount.py somefile.txt aardvark 1 anvil 3 ban 1 boat 4 be 19 ...

The program loads up a dictionary to count the words in the file, and then produces an alphabetic order list of each word with its count.

The file 'redblue.txt' has punctuation added to our old poem, so we can see how wordcount.py cleans up each word for counting. The file 'alice-book.txt' has the whole text of the book Alice in Wonderland.

$ cat redblue.txt

Roses are red

Violets -are- blue

"RED" BLUE.

$

$ python3 wordcount.py redblue.txt

are 2

blue 2

red 2

roses 1

violets 1

$

$ python3 wordcount.py tale-of-two-cities.txt # 133k words

...lots...

youthful 3

youthfulness 1

youths 1

you—and 1

you—are 1

you—does 1

you—forgive 1

you—ties 1

zealous 2

$

This is the core of the program. Reads the text of the file, splits it into individual words. Converts each word to a clean, lowercase form. Builds and returns a counts dict, counting how many times each word occurs, like this:

counts = {

'bear': 4,

'able': 1,

'the': 113,

'coffee': 5,

...

}

The code to read the text and build the counts dict is below, and explanations of sub-parts follow afterwards.

def read_counts(filename):

"""

..Docstring..

"""

counts = {}

# Standard file code: open file, loop to process each line

with open(filename) as f:

for line in f:

line = line.strip()

# Split the line into words, loop to process each word

# split() with no params -> splits on whitespace

words = line.split() # See note-1 below

for word in words:

word = word.lower()

word = clean(word) # clean('--woot!') -> 'woot'

if word != '': # Tricky - cleaning may leave ''

if word not in counts:

counts[word] = 0

counts[word] += 1

return counts

s.split() TrickNormally we split like this: parts = line.split(',')

However, calling s.split() with no parameters within the parenthesis performs a special "whitespace" split,

looking for chars like space and newline to separate the text into pieces.

>>> line = 'Here are, words on a line.\n' >>> line.split() ['Here', 'are,', 'words', 'on', 'a', 'line.']

It doesn't have any knowledge of language to separate the "words" exactly. It just separates where there is one or more whitespace char, which is good enough.

The clean(s) function is used to clean punctuation from the edges of words, like given '--woot!' extract just 'woot'. It is written as a black-box function with Doctests, of course! The counting code uses this to clean up each word pulled from the file.

clean('--woot!') -> 'woot'

clean('red.') -> 'red'

Look at source code and Doctests of clean() in wordcount.py

The other major function in wordcount.py is the print_counts() function — it takes in a counts dict parameter, and uses the standard v1 sorted-keys print code seen above. This prints out all the words and their counts, one per line, in alphabetical order. This code is what produces the alphabetized output above.

def print_counts(counts):

"""

Given counts dict, print out each word and count

one per line in alphabetical order, like this

aardvark 1

apple 13

...

"""

for word in sorted(counts.keys()):

print(word, counts[word])

The wordcount program is a sort of Rosetta stone of coding - it's a working demonstration of many important features of a computer program: strings, dicts, loops, parameters, return, decomposition, testing, sorting, files, and main(). If you need to remember some bit of Python syntax, there's a good chance there's an example in this program. Or if you are learning a new computer language, you could try to figure out how to write wordcount in the new language to get started.

Try running wordcount.py on file tale--of-two-cities.rxr - the full text of the book, 133,000 words. Time the run of the program, see if the dic†/hash-table is as fast as they say. The command line "time" command times how long it takes for a program to complete (the Windows equivalent is shown below). The second run will be a little faster, as the file is cached in memory by the operating system.

$ time python3 wordcount.py tale-of-two-cities.txt ... lots of printing ... zealous 2 real 0m0.122s user 0m0.083s sys 0m0.020s

Here "real 0.122s" means regular clock time, 0.122 of a second, aka 122 milliseconds, aka a little more than a tenth of a second elapsed to run this program from start to finish.

Note in Windows, you need the "Powershell" terminal, not the more primitive terminal PyCharm may be set for. Here are instructions for enabling PowerShell.

The Windows PowerShell equivalent to "time" is:

$ Measure-Command { py wordcount.py tale-of-two-cities.txt }

There are about 133,000 words in the Tale of Two Cities. How many accesses to the dict are there for each word, conservatively:

if word not in counts: # 1 dict "in"

counts[word] = 0 # (not counting this one)

counts[word] += 1 # 1 dict get, 1 dict set

Each word hits the dict at least 3 times: 1 "in", then we don't count the possible = 0, then 1 get and 1 set for the += line. So how long does each dict access take?

>>> 0.122 / (133000 * 3) 3.0576441102756893e-07

Ten to the -7 is a tenth of a millionth of a second, so with our back-of-envelope math here, the dict is taking 3/10 of a millionth of a second per dict access. In reality it's faster than that, as we are not separating out the time for the file reading, splitting, and word-cleaning which went in to the 0.122 seconds. Nonetheless the basic claim about dicts is here. The dict is very fast accessing per key, even if the number of keys is large. In CS106B, you look at the internals of the dictionary more closely.

The other theme here is being quantitative with our own code — running it a couple different ways, getting some numbers to think about how our algorithm works.

See also Python guide Lists

We'll call the basic list features we've used so far the 1.0 features - you can get quite far with just these.

>>> nums = [] >>> nums.append(1) >>> nums.append(0) >>> nums.append(6) >>> >>> nums [1, 0, 6] >>> len(nums) 3 >>> >>> nums[0] 1 >>> 6 in nums True >>> 5 not in nums True >>> nums.index(6) 2 >>> >>> for n in nums: ... print(n) ... 1 0 6

Now let's see a few more list features...

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> lst2 = lst[1:] # slice without first elem >>> lst2 ['b', 'c', 'd'] >>> lst ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> lst3 = lst[:] # copy whole list >>> lst3 ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> # can prove lst3 is a copy, modify lst >>> lst[0] = 'xxx' >>> lst ['xxx', 'b', 'c', 'd'] >>> lst3 ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

Now we'll look at some functions that are related to lists and we will use all of these.

>>> nums = [45, 100, 2, 12] >>> sorted(nums) # numeric [2, 12, 45, 100] >>> >>> nums # original unchanged [45, 100, 2, 12] >>> >>> sorted(nums, reverse=True) [100, 45, 12, 2] >>> >>> strs = ['banana', 'apple', 'donut', 'arple'] >>> sorted(strs) # alphabetic ['apple', 'arple', 'banana', 'donut'] >>>

>>> min([1, 3, 2]) 1 >>> max([1, 3, 2]) 3 >>> min([1]) # len-1 works 1 >>> min([]) # len-0 is an error ValueError: min() arg is an empty sequence >>> >>> min(['banana', 'apple', 'zebra']) # strs work too 'apple' >>> max(['banana', 'apple', 'zebra']) 'zebra' >>> >>> min(1, 3, 2) # works w/ params instead of list 1 >>> max(1, 3, 2) 3

Compute the sum of a collection of ints or floats, like +.

>>> nums = [1, 2, 1, 5] >>> sum(nums) 9

Strategy: prefer using Python built-ins to writing the code yourself.

Look at the "listpat" exercises on the experimental server

> listpat exercises. This section starts with basic "accumulate" pattern problems. The later problems require more sophisticated state-machine solutions.

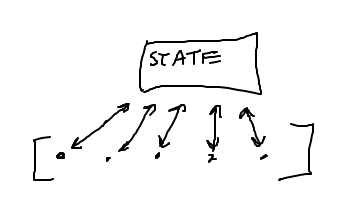

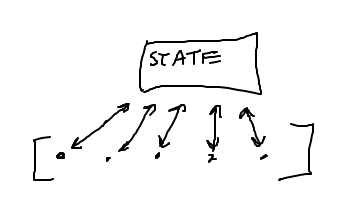

state = init

for elem in lst:

...

elem <-> state

...

return f(state)

Many functions we've done before actually fit the state-machine pattern. Start the state variable as empty, += in the loop. Known as the "accumulate" pattern — start a variable empty, built up the answer there.

# 1. init state before loop result = '' loop: .... # 2. update in the loop if xxx: result += yyy # 3. Use state to compute result return result

Use the state-machine strategy outlined below to solve something a little more interesting.

> min()

Style "len" variable name rule: we have Python built-in functions like len() min() max() list(). Avoid creating a variable with the same name as an important function, such as "min" or "list". This is why our solution uses "best" as the variable to keep track of the smallest value seen so far instead of the more natural "min".

def min(nums):

# best tracks smallest value seen so far.

# Compare each element to it.

best = nums[0]

for num in nums:

if num < best:

best = num

return best

If we think about it carefully, we could loop over nums[1:] to avoid one comparison, but that extra complication is not worthwhile.

Say sections of '@..!' sections in a string should be changed to uppercase, like this:

'This code @has no bugs! probably' -> 'This code HAS NO BUGS probably' 'I @am hungry! right @now!' -> 'I AM HUNGRY right NOW'

1. Have a boolean variable up_mode - True if changing chars to uppercase, False otherwise. Init to False.

2. When seeing a '@' or '!', change up_mode to True or False as appropriate

3. When processing a regular ch, look at up_mode to see what to do

4. Use an if/elif structure to look for '@' '!' or regular char

up_mode: FFFFFFFFFFTTTTTTTTTTTTTFFFFFFFFF

'This code @has no bugs! probably'

|

v

'This code HAS NO BUGS probably'

def upper_code(s):

result = ''

up_mode = False # State variable

for ch in s:

# Detect: @, !, regular char

if ch == '@':

up_mode = True

elif ch == '!':

up_mode = False

else:

if up_mode:

result += ch.upper()

else:

result += ch

return result

The else: in effect is checking that the char is not '@' or '!', since we don't want to put those in the result. Could write it as:

if ch != '@' and ch != '!':

Say we have a code where most of the chars in s are garbage. Except each time there is a digit in s, the next char goes in the output. Maybe you could use this to keep your parents out of your text messages in high school.

'xxyy9H%vvv%2i%t6!' -> 'Hi!'

I can imagine writing a while loop to find the first digit, then taking the next char, .. then the while loop again ... ugh.

take_next VarHave a boolean variable take_next which is True if the next char should be taken (i.e. the char of the next iteration of the loop) and False otherwise.

Write a nice, plain loop through all the chars. Set take_next to True when you see a digit. For each char, look at take_next to see if it should be taken. Set it back to False when a char is taken. The exact details of the code in the loop are unusually tricky.

This is such a nice approach vs. trying to solve it with a bunch of while loops.

Type in some code that is an attempt. Run it, see the output, work from there. Compared to most problems, I think this problem is easiest to debug by looking at the wrong output. Put some code in there, run it, and go from there.

You could solve this using index numbers and -1. However, it's worth working out this state-machine approach which does not rely on index numbers at all.

def digit_decode(s):

result = ''

take_next = False

for ch in s:

if take_next:

result += ch

take_next = False

if ch.isdigit():

take_next = True

# Set take_next at the bottom of the

# loop, taking effect on the next char

# at the top of the loop.

return result

Above solution sets take_next at the bottom of the loop, but reads it at the top of the loop. In this way, the digit on char index n affects the char at index n + 1, but the structure is a little subtle.

Another approach would be to use if/else to avoid using take_next on the same iteration that it is set.

Social Security Administration's (SSA) baby names data set of babies born in the US going back more than 100 years. This part of the project will load and organize the data. Part-b of the project will build out interactive code that displays the data.

New York Times: Where Have All The Lisas Gone. This is the article that gave Nick the idea to create this assignment way back when.

This is an endlessly interesting data set to look through: john and mary, jennifer, ethel and emily, trinity and bella and dawson, blanche and stella and stanley, michael and miguel.

Optional more state-machine ideas.

Previous pattern:

# 1. Init with not-in-list value previous = None for elem in lst: # 2. Use elem and previous in loop # 3. last line in loop: previous = elem

Here is a visualization of the "previous" strategy - the previous variable points to None, or some other chosen init value for the first iteration of the loop. For later loops, the previous variable lags one behind, pointing to the value from the previous iteration.

count_dups(): Given a list of numbers, count how many "duplicates" there are in the list - a number the same as the value immediately before it in the list. Use a "previous" variable.

The init value just needs to be some harmless value such that the == test will be False. None often works for this.

def count_dups(nums):

count = 0

previous = None # init

for num in nums:

if num == previous:

count += 1

previous = num # set for next loop

return count

A neat example of a state-machine approach.

The "hat" code is a more complex way way to hid some text inside some other text. The string s is mostly made of garbage chars to ignore. However, '^' marks the beginning of actual message chars, and '.' marks their end. Grab the chars between the '^' and the '.', ignoring the others:

'xx^Ya.xx^y!.bb' -> 'Yay!'

Solve using a state-variable "copying" which is True when chars should be copied to the output and False when they should be ignored. Strategy idea: (1) write code to set the copying variable in the loop. (2) write code that looks at the copying variable to either add chars to the result or ignore them.

There is a very subtle issue about where the '^' and '.' checks go in the loop. Write the code the first way you can think of, setting copying to True and False when seeing the appropriate chars. Run the code, even if it's not going to be perfect. If it's not right (very common!), look at the got output. Why are extra chars in there? How to rearrange the loop to fix it?