Today: loose ends - comprehension, truthy logic, #! line, float flaws, open source

List comprehensions are a beautiful Python feature. For certain problems, they are a short and unbeatable solution. If you are interviewing for an internship, and let slip that you like comprehensions, you will get a knowing nod from the interviewer, like "this kid gets it." (Not needed for any of our homeworks.)

[1, 2, 3, 4] -> [1, 4, 9, 15]

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums] [1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36] >>> [n * -1 for n in nums] [-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6] >>> >>> strs = ['the', 'donut', 'of', 'destiny'] >>> [s.upper() for s in strs] ['THE', 'DONUT', 'OF', 'DESTINY'] >>> [str(n) + '!!' for n in nums] ['1!!', '2!!', '3!!', '4!!', '5!!', '6!!']

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n + 10 for n in nums] [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] >>> [abs(n - 3) for n in nums] [2, 1, 0, 1, 2, 3]

Section on server: Comprehensions

> power2()

> diff21()

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] >>> [n for n in nums if n > 3] [4, 5, 6] >>> [n * n for n in nums if n > 3] [16, 25, 36]

These are all 1-liner solutions with comprehensions.

Syntax reminder - e.g. make a list of nums doubled where n > 3

[2 * n for n in nums if n > 3]

> even_ten (has if)

> up_only (has if)

Comprehensions are easier to write than map(), so you can use them instead. Why did we learn map() then? Because map() is the ideal way to see how lambda works. At this point, you can use comprehensions instead of map, (and exam problems will give full credit to either form, your choice).

Programmers can get into Comprehension Fever - trying to write your whole program as nested comprehensions. Or it may be a spirit of one-upmanship, like shrinking down the code more than everyone else. However, using comprehensions for everything is a mistake. Comprehensions are so dense, they can be unreadable if too long. Probably 1-line is the sweet spot for a comprehension.

Using regular functions, loops, variables etc. for longer phrases is fine.

There are lines of Python code we have glossed over. Today we will explain these.

Usual practice: to create a new Python file, copy an existing Python file you have laying around. In this way, you get the #!/usr/bin... and other bits of rote syntax mentioned here.

What is up with that very first line: #!..

#!/usr/bin/env python3 """ Stanford CS106A Pylibs Example ...

#!/usr/bin/env python3#!/usr/bin/python - python2This is an older form of the first line.

This first line specifies that the file is Python 2 code

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

...

There are not huge differences between Python version-2 and version-3. You could easily write Python-2 code if you needed to, but Python-3 is strongly preferred for all new work.

Legacy code - that said, many orgs may have old "legacy" python-2 programs laying around, and it's easiest if they just use them and don't update or edit them. The first line #!/usr/bin/env python3 is a de-facto way of marking which version the file is for.

You do not need to remember all those details. Just remember this: have that if-statement at the bottom of your file as a couple boilerplate lines. It calls the main() function when this file is run on the command line.

...

... python file ..

...

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

When you run a program from the command line like this, Python loads the whole file, and then finally calls its main() function.

$ python3 pylibs.py

The if-statement shown above is the bit of code that calls main(). It's a historical quirk that Python does not simply call main() automatically, but it doesn't, so we have this if-statement at the bottom of the file.

Typically, when starting a new Python project, you copy a Python file you have laying around. In this way, you get the boilerplate #!/usr/bin.. line at the start, and this if-main line at the end of the file.

Say you run a program like this:

$ python3 wordcount.py poem.txt

In that case, the if __main__ expression will be True. What does it do? It calls the main() function. So if the python file is run from the command line, call its main() function. That is the behavior we want, and it is what the above "if" does.

What is the other way to load a python file? There is some other python code, and that code imports the python file.

# In some other Python file # and it imports wordcount ... import wordcount

In this more unusual case, the above "if" will be False. Loading a python file (module) does not run its main(). So the if-statement runs main() when the python file is itself run from the command line, but does not run main() when the file is imported by another file.

# int 3 100 -2 # float, has a "." 3.14 -26.2 6.022e23

Note: do not panic! We can work with this. But it is shocking.

What is happening here?

>>> 0.1 0.1 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 0.2 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 # this is why we can't have nice things 0.30000000000000004 >>> >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.4 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.5 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.6 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.7 >>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 0.7999999999999999 # here the garbage is negative >>> 7 * 0.1 0.7000000000000001

Another example with 3.14

>>> 3.14 * 3

9.42

>>> 3.14 * 4

12.56

>>> 3.14 * 5

15.700000000000001 # d'oh

Conclusion: float math is slightly wrong

The short answer, is that with a fixed number of bytes to store a floating point number in memory, there are some unavoidable problems where numbers have these garbage digits off to the right. It is similar to the impossibility of writing the number 1/3 precisely as a decimal number — 0.3333 is close, but falls a little short.

>>> a = 3.14 * 5 >>> b = 3.14 * 6 - 3.14 >>> a == b # Observe == not working right False >>> b 15.7 >>> a 15.700000000000001

>>> a = 3.14 * 5 >>> b = 3.14 * 6 - 3.14 >>> >>> import math >>> math.isclose(a, b) True >>> >>> abs(a - b) < 0.0001 True >>>

>>> # Int arithmetic is exact >>> # The two expressions are exactly equal, "precise" >>> 2 + 3 5 >>> 1 + 1 + 3 5 >>> >>> 2 + 3 == 1 + 1 + 3 True >>>

Doesn't seem like such a high bar .. and yet float does not give us this!

Bank balance example: Float is not a good choice for bank balances. Customers do not want to see math a little bit off. Bank balances can be stored as int number of pennies. That way, adding and subtracting from one account to another comes out exactly right and balanced.

# balance is $ 457.12 # store as int pennies bal = 45712 # withdraw $10, i.e. 1000 pennies bal -= 1000 # balance is exactly right bal == 44712 # when printing, put in the '.' '447.12'

In fact, Bitcoin wallets use exactly this int strategy - the amount of bitcoin in a wallet is measured in "satoshis". One satoshi is one 100-millionth of 1 bitcoin. Each balance is tracked as an int number of satoshis, e.g. an account with 0.25 Bitcoins actually has 25,000,000 satoshis. Using ints in this way, the addition and subtraction to move bitcoin (satoshis) from one account to another comes out exactly correct. int is precise!

# bitcoin wallet containing 0.25 # actually int 25,000,000 satoshis bal = 25000000 # spend 0.1 bitcoin, int 10,000,000 bal -= 10000000 # balance comes out exactly right bal == 15000000

Optional - if we have time.

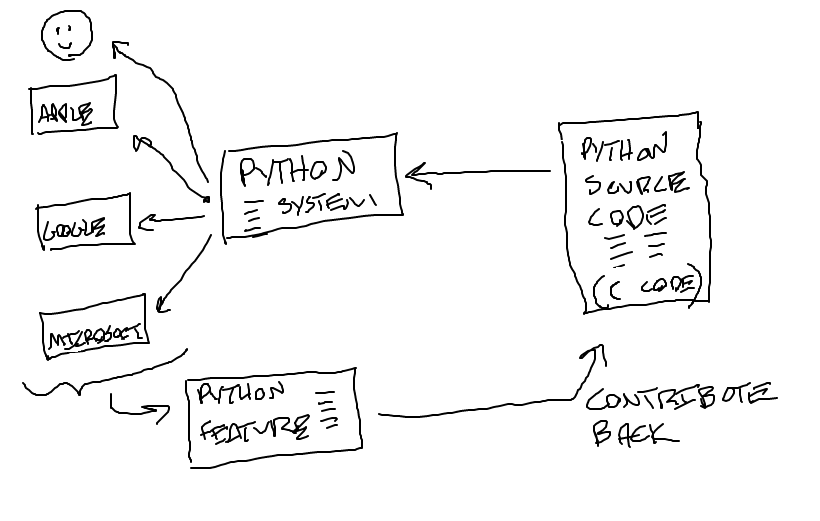

You have noticed that Python works well on your machine, and yet it's free. How does that work? Python is a great example of "open source" software.

Much of the internet is based on open standards - TCP/IP, HTML, JPEG - and open source software: Python (language), Linux (operating system), R (statistics system).

Let's look at Python