This page is the reference documentation for the simple Bit robot used in CS106A. We'll use Bit for our first examples as an on-ramp for Python code in CS106A (the robot is Nick's research project). The robot actions are controlled by lines of Python code, and each action has a clear visual result. The simple cause-and-effect nature of the code makes a good introduction to how Python code works.

The lecture notes run through a series of bit examples. This page is a reference for Bit's functions.

The bit robot sits on a square within a rectangular world of squares. Bit always faces one of the four cardinal directions.

Here is drawing of a world with bit in the upper left square, facing the right side of the world. Here Bit is shown as a plain "V" shape, pointing the direction the robot is facing.

Bit can perform a small number of actions in the world. Bit can "move", advancing forward one square in the direction Bit is facing. Here Bit moves forward one square:

Bit can turn 90 degree left or right. Here bit turns 90 degrees right, so now facing the bottom of the world.

Bit can paint the currently occupied square to be red, green, or blue. Here Bit paints its square red.

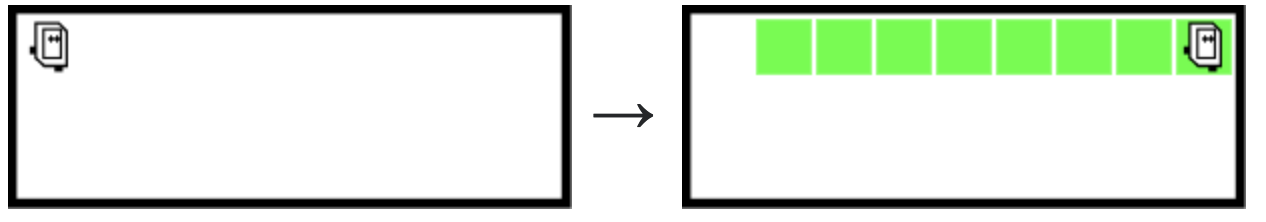

Here is a typical picture of Bit, midway through solving a problem — Bit started at the left side of the world and is moving towards the right side. Bit painted the first square green, and is painting the later squares blue. The solid black squares and the four black edges of the world are not "clear" for a move, and it's an error for Bit to move into those black obstacles. All the other squares, painted or blank, are clear for a move.

The drawings so far have shown Big as a plain "V" icon. There is also a "classic" icon, showing bit as a little robot with the eyes facing the way bit is facing. Here is the same world a shown above, but using the classic robot icon. You can use either icon, and it makes no difference to the code. We admit to having some nostalgic warmth for the old robot icon.

The software supports both icons and you can use whichever you prefer.

Bit is always located on a square in the world, facing one of the four directions. Bit can take just a few actions in the world, and each action corresponds to a Python "function" that performs that action.

Here is a picture of bit at the upper left of a world, before taking some actions:

If bit then does these actions:

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right()

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

Then the world will look like this:

Often we'll write a Python function that contains a series of Bit code lines to solve a problem. For example, here is a function named "go", which creates bit on its first line and calls functions to move bit over a couple squares with some painting.

def go(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right()

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

Empty squares are called "clear", and Bit can move into them, so front_clear() returns `True` when the square in front of Bit is clear. Here the square in front is shown as a dotted red circle:

Solid black squares and the black edges of the world are not clear for moves, so front_clear() returns False in those cases.

It's common to use bit.front_clear() as the test in a while-loop, with bit.move() in the loop body — the effect is to move Bit forward in a line until reaching a black square or the side of the world. For example, this is the code for the CS106A go-green example

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

Your code is shielded from the details, but a bit world is stored in

a plain text file with a name like '5x4.world' or 'super-spiral.world'.

The function "Bit" (uppercase 'B') is a function which takes a filename parameter

(e.g. '5x4.world'), reads the rectangular world into memory with a bit in it, and returns a reference to the bit. A bit always exists within the context of a specific world in this way.

So your code can create a bit in, say, a world named '5x4.world' like this:

bit = Bit('5x4.world')

That results in a memory structure like this, ready to run more bit functions to run and change the world.

More often the first line in a function looks like the following, where the filename of the world is passed in as a parameter:

def do_something(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

bit.move()

...

The filename is passed in as a parameter which holds the name of the file, e.g. '5x4.world', and the first line

creates bit from the that filename and the bit operations go from there.