Trees

CS 106B: Programming Abstractions

Spring 2021, Stanford University Computer Science Department

Lecturer: Chris Gregg, Head CA: Chase Davis

Slide 2

Announcements

- Assignment 5 is due tomorrow (late extension until Sunday), and Assignment 6 is due next Wednesday

- We will post Assignment 6 today. It is a scaled-back assignment, so should be doable by Wednesday

- You should start working on your personal project

- The personal project is your final assessment!

Slide 3

Today's Topics

- Refresh on what pointer diagrams represent

- Quick comment on doubly-linked lists

- Introduction to the tree data structure

- You've already seen lots of tree structures

- Tree terminology

- How do we build trees programatically?

- Writing code to traverse a tree

Slide 4

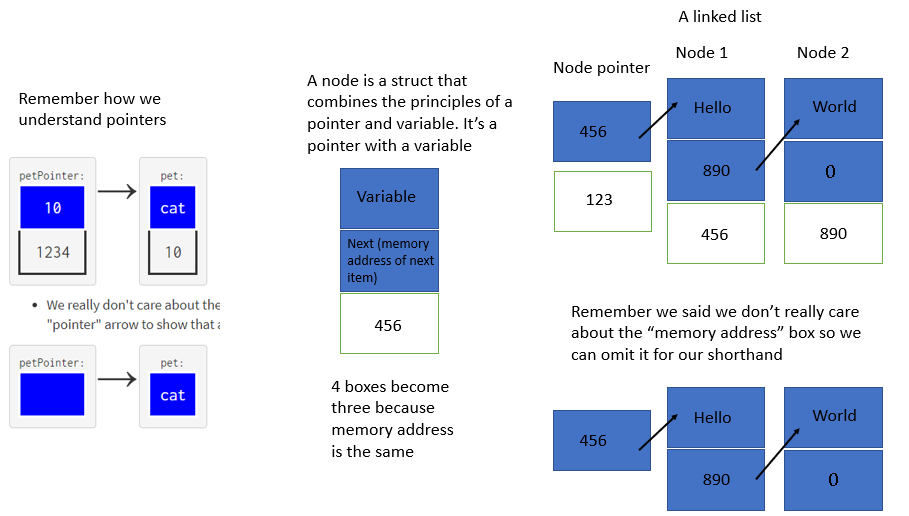

Pointer Diagram Refresh

- The following diagram was put together by a student last Spring:

- Pointers have values that are memory addresses.

- All variables and objects have their own memory address where they are located

- The

nextpointer is a memory address

Slide 5

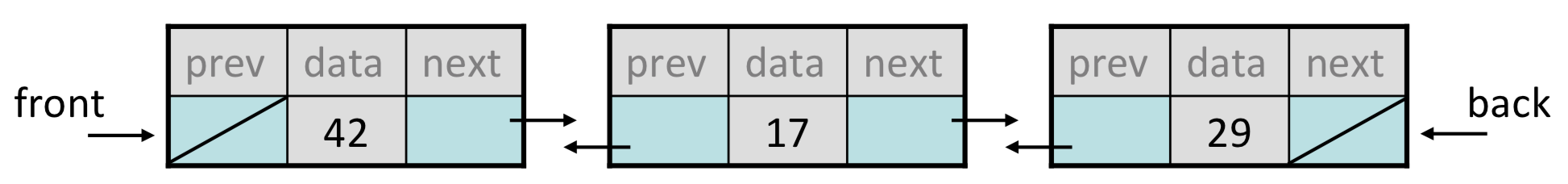

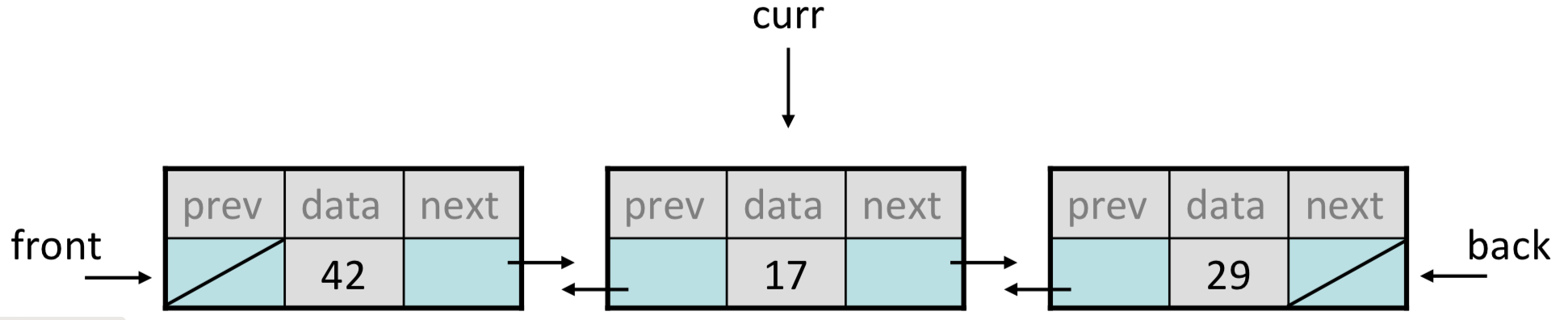

Doubly-linked lists

- Last time, we discussed linked lists. Specifically, we discussed singly linked lists, which have a single

nextpointer in each node, and are strictly one-way. - We also can create a doubly linked list, which has pointers in both directions:

struct ListNode { int data; ListNode* prev; ListNode* next; }; - We will keep a

_frontand a_backpointer in the class, too:class DoublyLinkedList { ... private: ListNode* _front; ListNode* _back; }; -

We can draw the nodes sideways for a bit more intuitive pictures: ```

- We can traverse in either direction with a doubly linked list:

ListNode* curr = _front; // print in forward order while (curr != nullptr) { cout << curr->data; curr = curr->next; } ListNode* curr = _back; while (curr != nullptr) { // print in reverse order cout << curr->data; curr = curr->prev; }

Slide 6

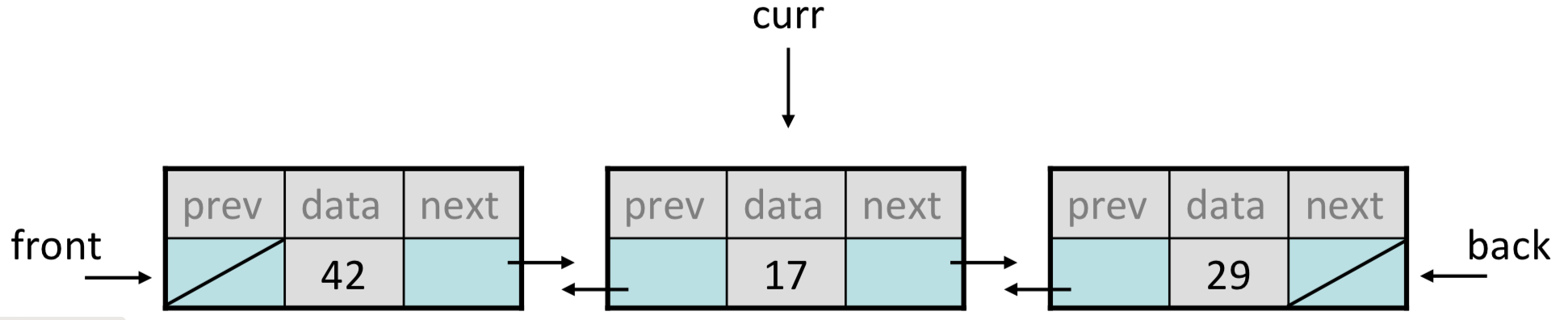

Adding nodes to a doubly linked list

- If we want to add a new node to a doubly-linked list, we don't have to stop on the previous node, and we could find the node in either direction.

- However, we have to change four pointers, which can make coding up a doubly lnked list tricky.

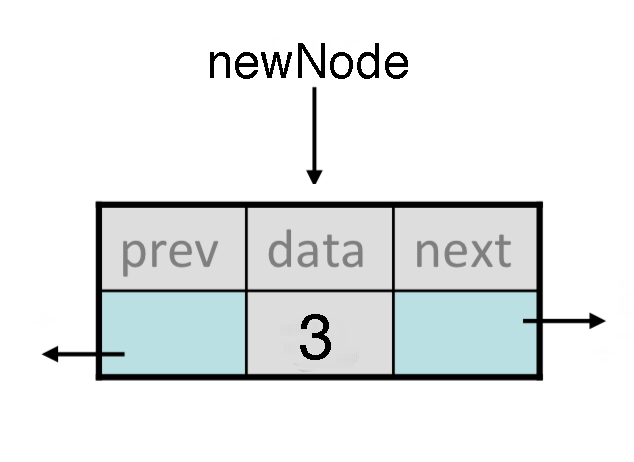

- Let's say we want to add the following

newNodebefore the 17, and we havecurron the 17:

- We would have to change four different pointers. Here's how we would make those changes (and order is important!):

curr->prev->next = newNode; newNode->prev = curr->prev; curr->prev = newNode; newNode->next = curr;Removing nodes from a doubly linked list

- If we want to remove a new node to a doubly-linked list, we don't have to stop on the previous node, and we could find the node in either direction.

- In this case, we only have to make changes to two pointers, the previous node's

next, and the next node'sprev. - Let's say we want to remove the 17 from the list below, and we've stopped

curron that node:

- Here are the changes we have to make:

curr->prev->next = curr->next; curr->next->prev = curr->prev; delete curr;

Slide 7

Trees

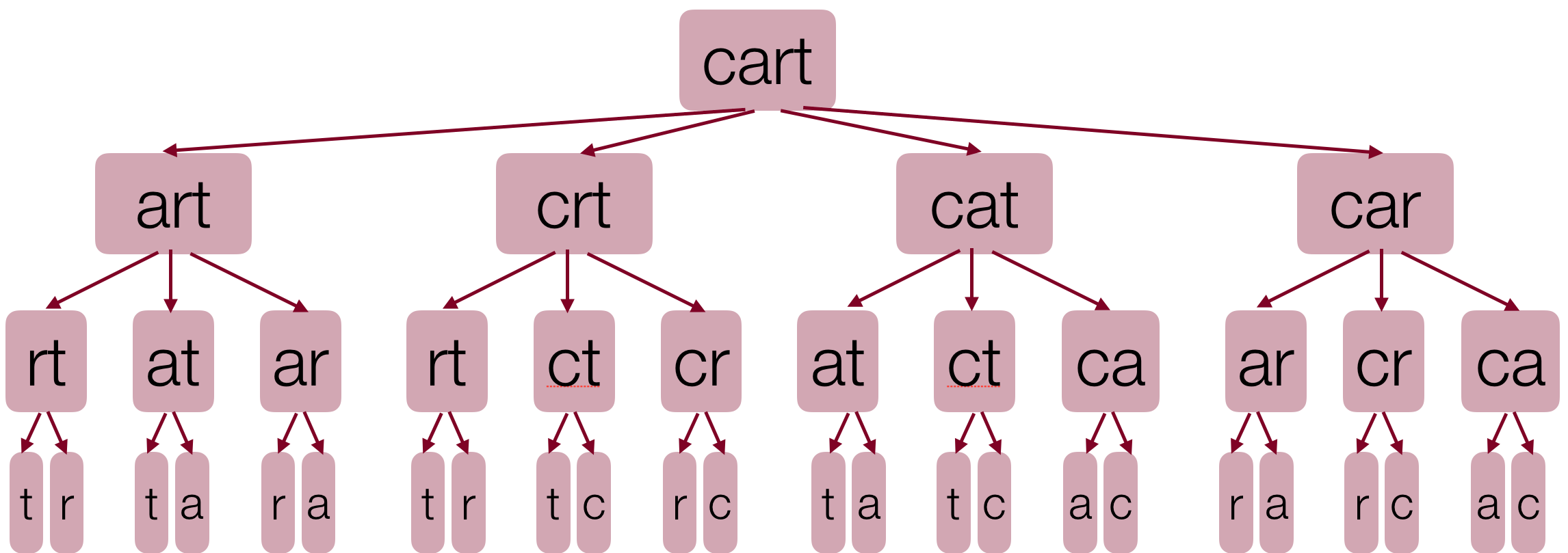

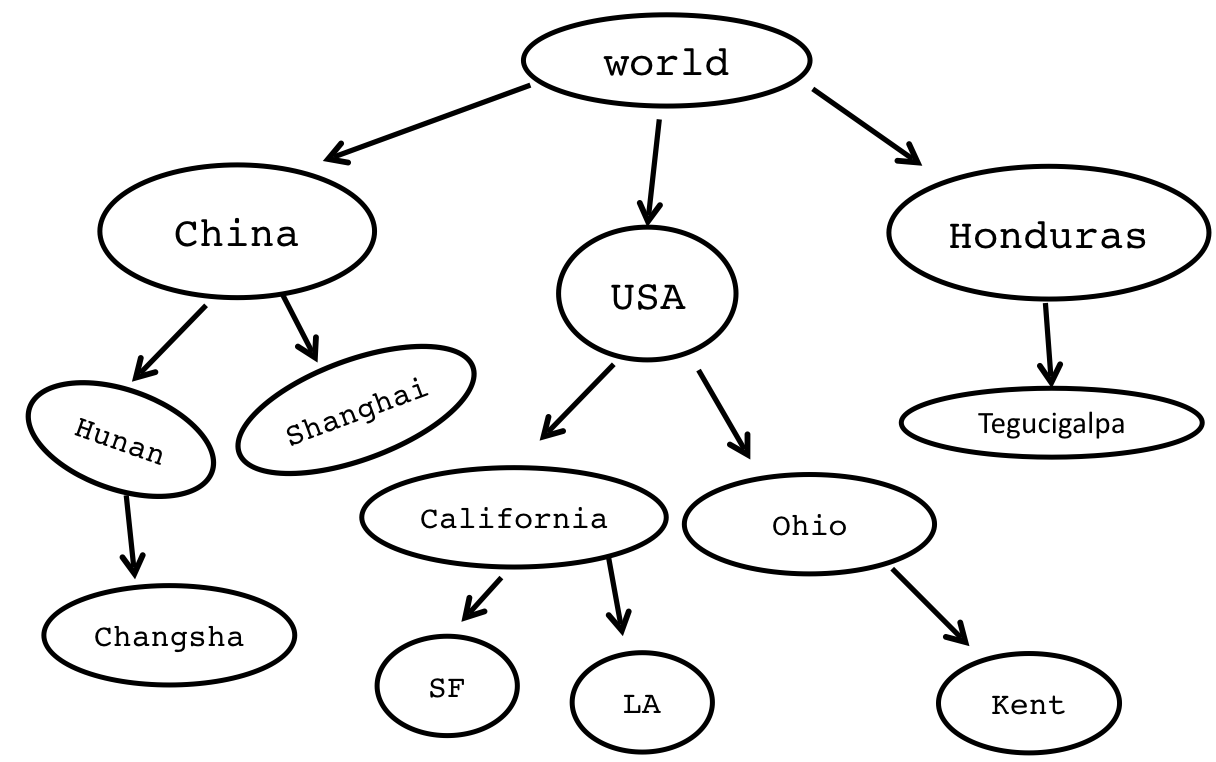

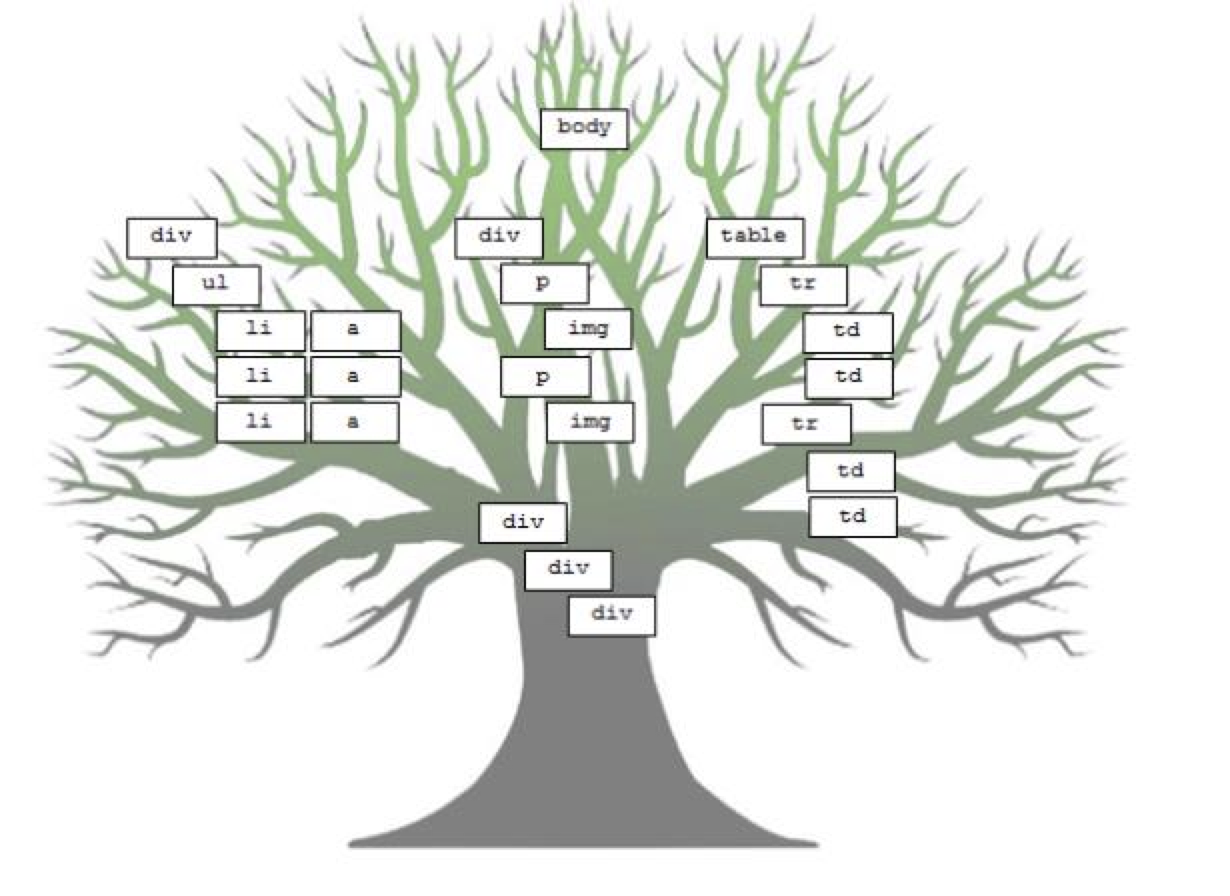

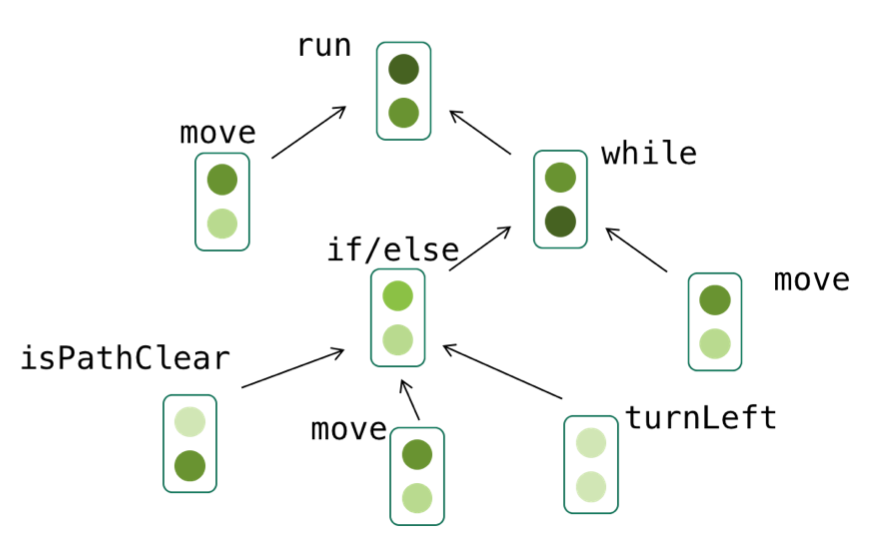

- We have seen trees in this class before, in the form of decision trees:

- Trees can describe hirearchies:

- Trees can describe websites:

- Trees can desceribe programs (we often call them abstract syntax trees (the following is a figure in an academic paper written by a recent CS 106 student!)

// Example student solution function run() { // move then loop move(); // the condition is fixed while (notFinished()) { if (isPathClear()) { move(); } else { turnLeft(); } // redundant move(); } }

Slide 8

Trees are inherently recursive

- What is a tree in computer science?

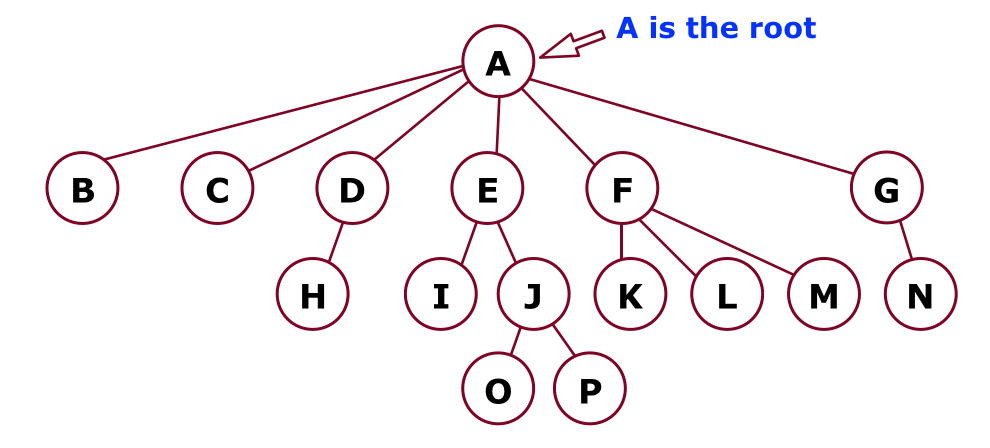

- A tree is a collection of nodes, which can be empty. If it is not empty, there is a root node,

r, and zero or more non-empty subtrees,T1,T2, …,Tk, whose roots are connected by a directed edge fromr.

- A tree is a collection of nodes, which can be empty. If it is not empty, there is a root node,

(root)

-----------A--------------

↙︎ ↙︎ ↙︎ ↓ ↘︎ ↘︎

B C D E F-- G

↙︎ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ ↘︎

H I J K L M N

↙︎ ↘︎

O P

- There are N nodes and N-1 edges in a tree.

- Tree terminology. In the diagram above:

- B is a child of A, and F is a child of A and a parent of K, L, M.

- Nodes with no children are leaves. Nodes B, C, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, and P are all leaves.

- Nodes with the same parent are siblings. I and J are siblings. K, L, and M are siblings. Nodes O and P are siblings. Nodes H and N do not have any siblings (only children).

Slide 9

More Tree Terminology

(root)

A--------------

↓ ↘︎ ↘︎

E F G

↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ ↘︎

I J K L M N

↙︎ ↘︎

O P

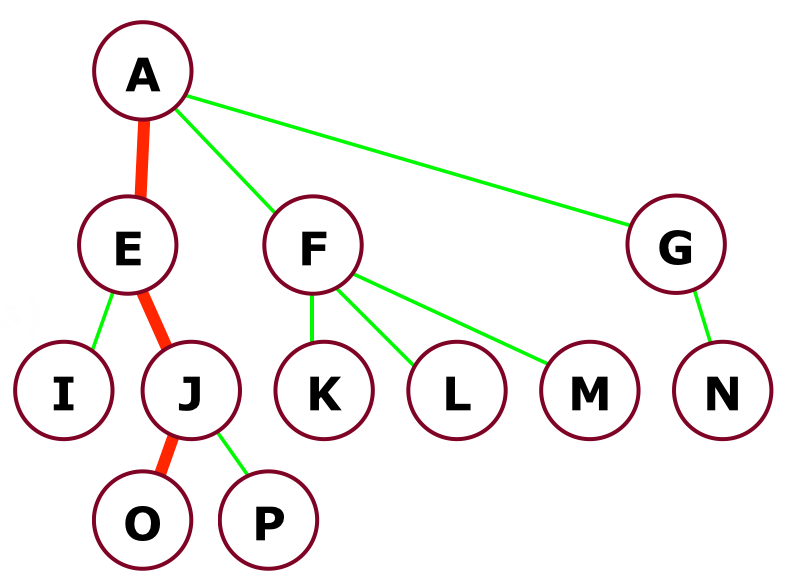

- We can define a path from a parent to its children. The path from A to O is: A-E-J-O.

- The path A-E-J-O has a length of three (the number of edges).

- The depth of a node is the length from the root. The depth of node J is 2. The depth of the root is 0.

- The height of a node is the longest path from the node to a leaf. The height of node F is 1. The height of all leaves is 0.

- The height of a tree is the height of the root. The height of the above tree is 3.

Slide 10

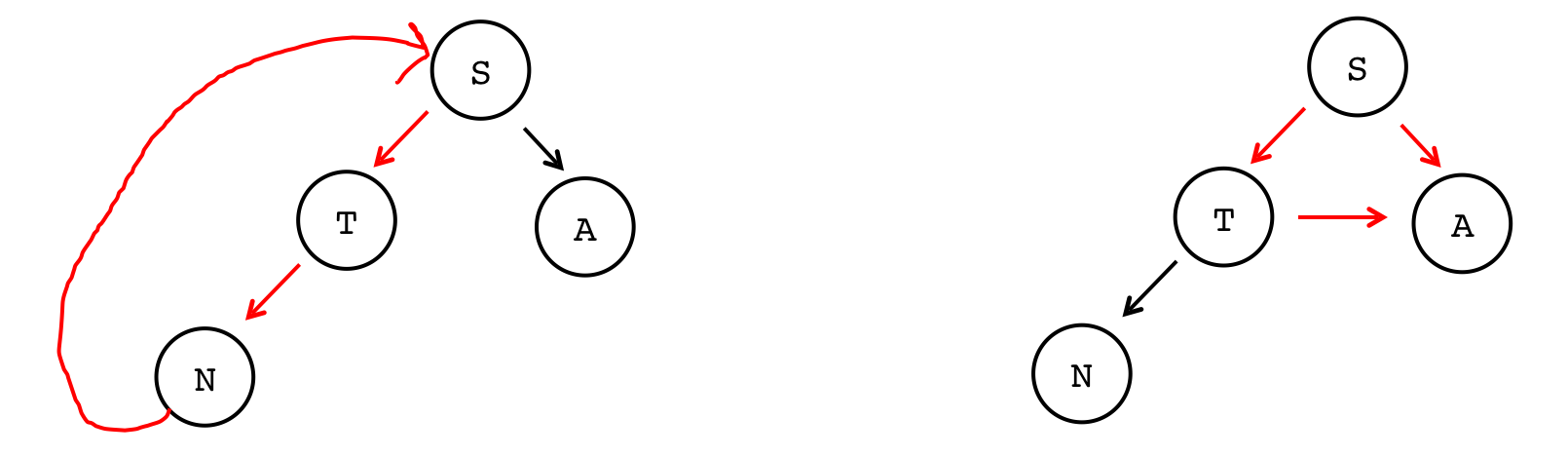

One Parent, No Cycles

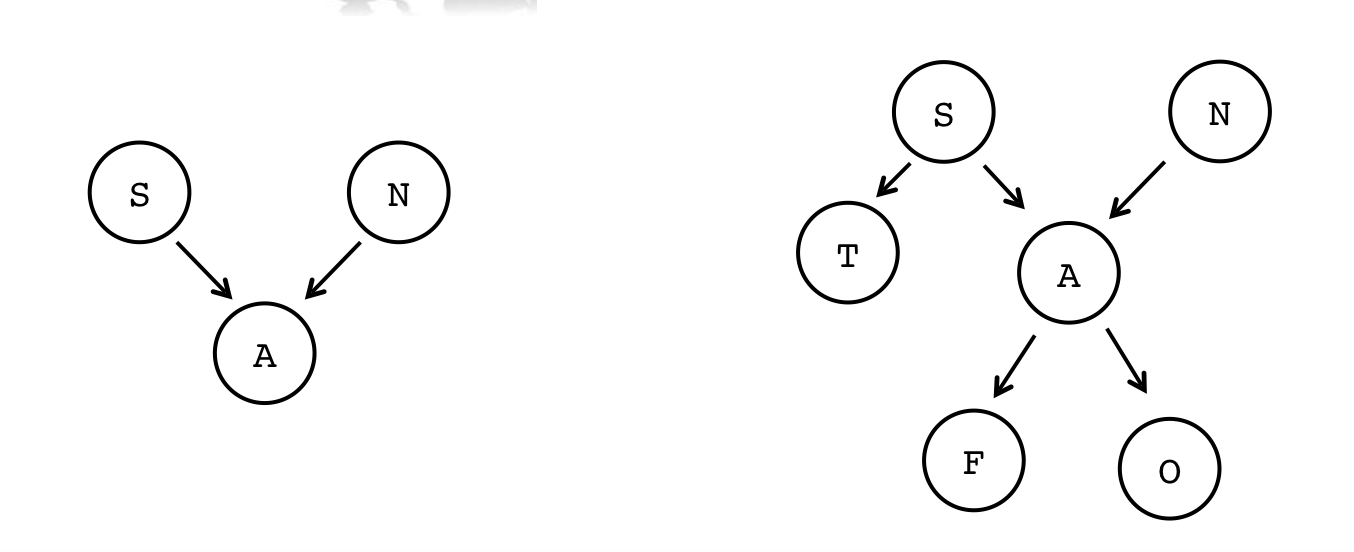

- Tree nodes can only have one parent, and they cannot have cycles

- Not a tree (A has two parents):

S N ↘︎ ↙︎ A - Again: not a tree (A has two parents):

S N ↙︎ ↘︎ ↙︎ T A ↙︎↘︎ F O - The following are not trees, either, because you can cycle through the tree. Nodes cannot have children that are on the same level or above on the tree:

- Not a tree (cycle from N back to S):

→→→→S ↑ ↙︎ ↘︎ ↑ T A ↑↙︎ N - Again: not a tree (the arrow from T to A causes a cycle):

S ↙︎ ↘︎ T→→→A ↙︎ N

Slide 11

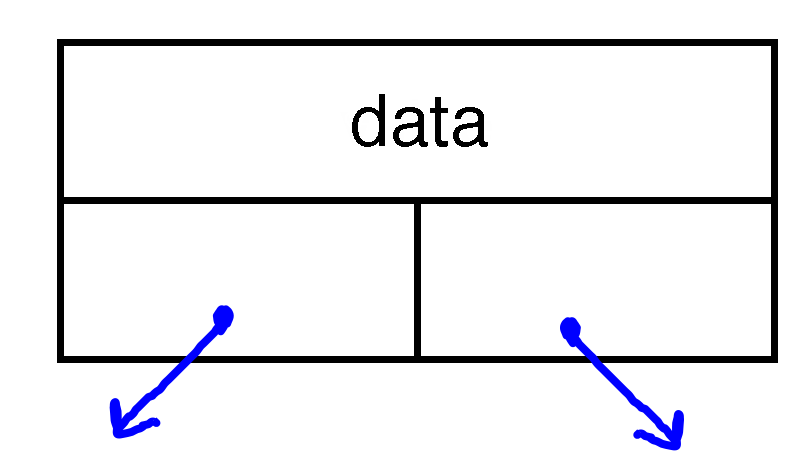

Building trees programatically

- To build a tree, we need a new version of our

Node. In this case, we want eachNodeto have a data value (like a linked list), but now we want to pointers, one to the left child, and one to the right child:struct TreeNode { string data; TreeNode* left; TreeNode* right; };

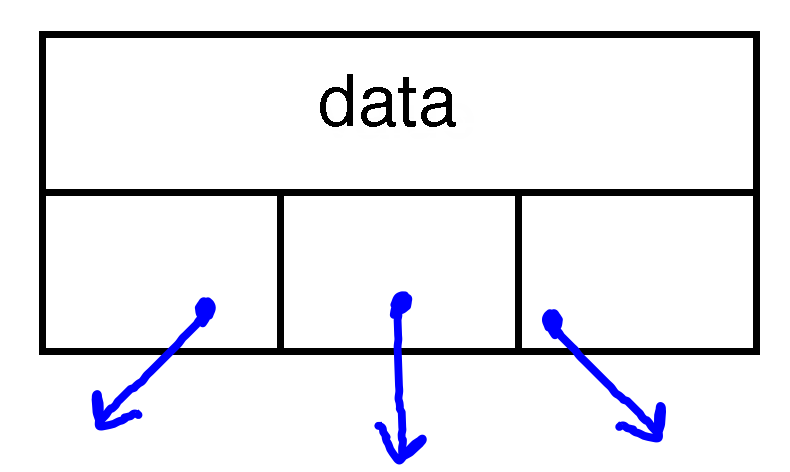

- We don't have to limit ourselves to binary trees, by the way: we could have a ternary tree:

struct TernaryTreeNode { string data; TernaryTreeNode* left; TernaryTreeNode* middle; TernaryTreeNode* right; };

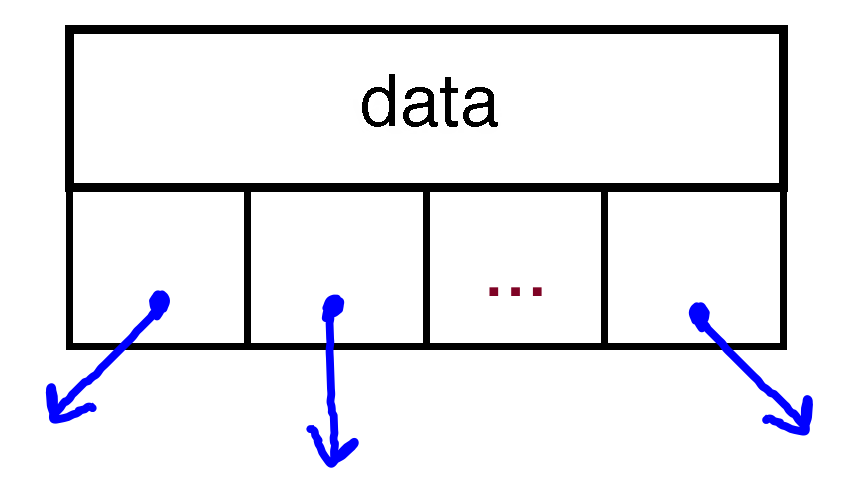

- In fact, we could have any number of children (we may look at the Trie data structure, which can be built this way). This is an N-ary Tree:

struct NAryTreeNode { string data; Vector<NAryTreeNode*> children; };

Slide 12

Traversing a Tree

- Often, we will want to do something with each node in a tree. Like linked lists, we can traverse the tree, but it is more involved because of all the branching.

- There are four different ways to traverse a binary tree:

- Pre-order

- In-order

- Post-order

- Level-order

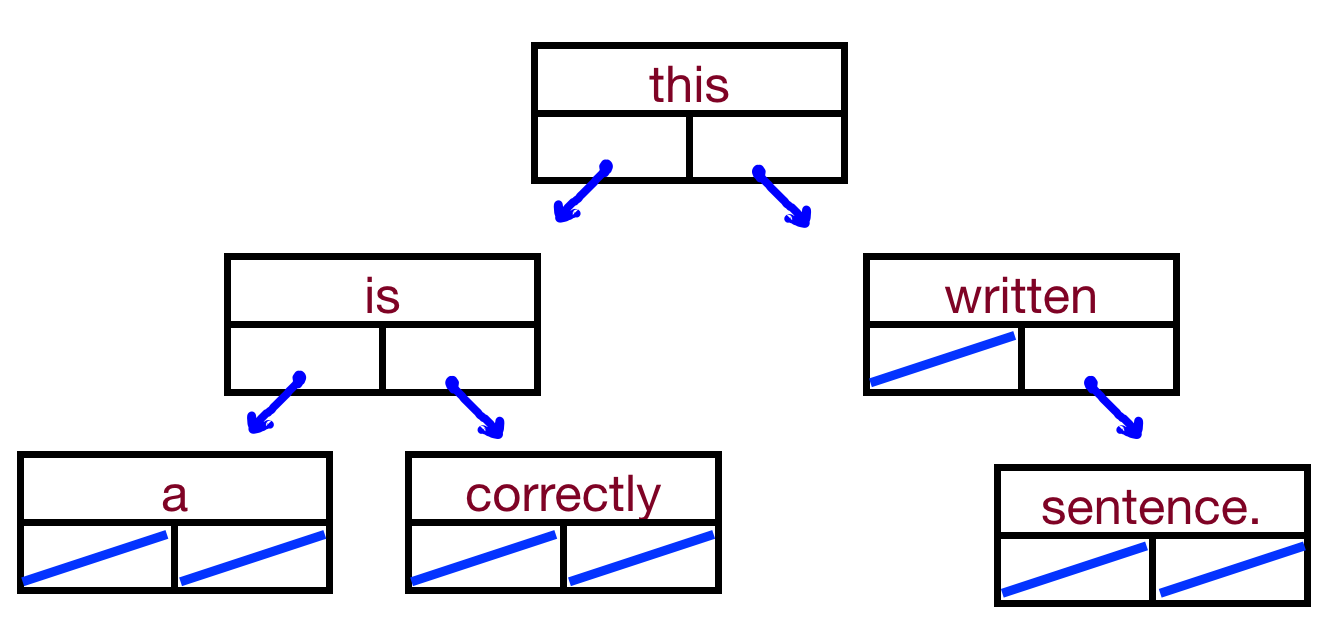

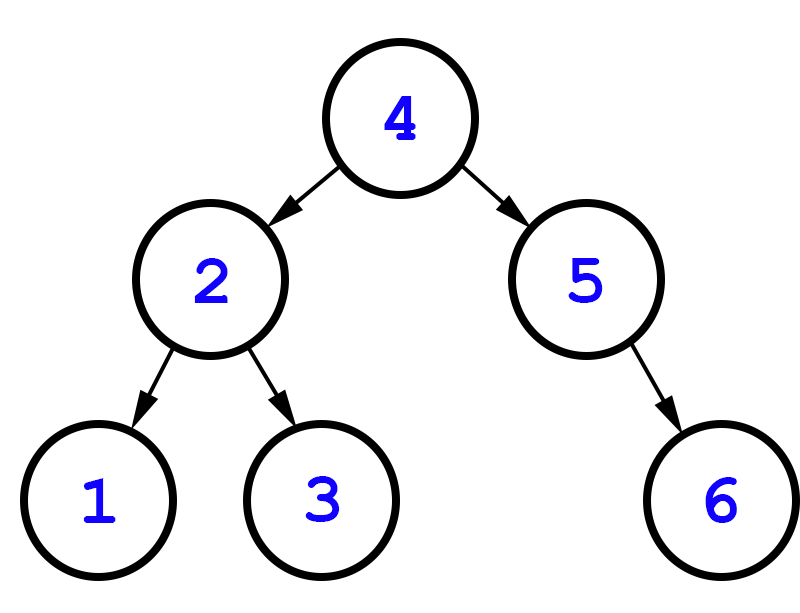

- Let's write some code for each traversal to see the differences. We'll look at two trees:

this ↙︎ ↘︎ is written ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ a correctly sentence - We'll also look at:

4 ↙︎ ↘︎ 2 5 ↙︎ ↘︎ ↘︎ 1 3 6 - By the way: trees do not have to be complete, like heaps. Any node can have 0, 1, or 2 children.

Slide 13

Pre-order traversal

- The algorithm for a pre-order traversal is as follows:

- Do something

- Go left

- Go right

- This is an inherently recursive algorithm

- For our tests, let's make the "Do something" part print the data at a particular node.

- Code:

void preOrder(TreeNode* tree) { if(tree == nullptr) return; cout<< tree->data <<" "; preOrder(tree->left); preOrder(tree->right); }

Slide 14

In-order traversal

- The algorithm for a in-order traversal is as follows:

- Go left

- Do something

- Go right

- This is also an inherently recursive algorithm

- Code:

void inOrder(TreeNode* tree) { if(tree == nullptr) return; inOrder(tree->left); cout<< tree->data <<" "; inOrder(tree->right); }

Slide 15

Post-order traversal

- The algorithm for a post-order traversal is as follows:

- Go left

- Go right

- Do something

- This is also an inherently recursive algorithm

- Code:

void postOrder(TreeNode* tree) { if(tree == nullptr) return; postOrder(tree->left); postOrder(tree->right); cout<< tree->data <<" "; }

Slide 16

Level-order traversal

- A level order traversal is different than all the others – we want to go one level at a time and print out each node, then go to the next level.

- For this tree, it would be:

this is written a correctly sentence

- Can we do this recursively!

- But, we can use an algorithm you've seen before: breadth first search!

- This is going to use a queue, just like the BFS you did for your maze solving assignment.

- Enqueue the root node

- While the queue is not empty

- dequeue a node

- do something with the node

- enqueue the left child if it exists

- enqueue the right child if it exists

- This is going to use a queue, just like the BFS you did for your maze solving assignment.

- Code:

void levelOrder(TreeNode *tree) { Queue<TreeNode *>treeQueue; treeQueue.enqueue(tree); while (!treeQueue.isEmpty()) { TreeNode *node = treeQueue.dequeue(); cout << node->value << " "; if (node->left != nullptr) { treeQueue.enqueue(node->left); } if (node->right != nullptr) { treeQueue.enqueue(node->right); } } }