Lab 2: C pointers/arrays/void *

Lab sessions Mon Apr 11 to Thu Apr 14

Lab written by Julie Zelenski

Learning goals

During this lab, you will:

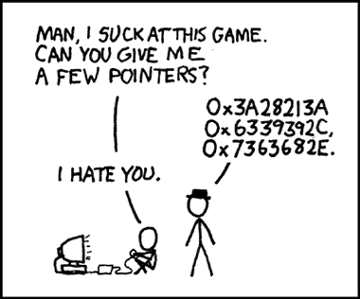

- investigate how arrays and pointers work in C

- write code that manipulates arrays and pointers

- use gdb and valgrind to help understand and debug your use of memory

First things first! Find an open computer to share with a partner. Introduce yourself and tell them about your favorite music to listen to while coding.

Lab exercises

-

Get started. Make a clone of the lab starter project using the command

hg clone /afs/ir/class/cs107/repos/lab2/shared lab2This creates the lab2 directory which contains source files and a Makefile. Pull up the online lab checkoff and have it open in a browser so you'll be able to jot down things as you go.

Optional: Some of you have asked about how you can set permissions so that both you and your partner can access the working directory. The

fs setaclcommand is used to change permissions. Some examples are shown below, replacedirnameandusernamewith the directory and sunet you wish to change.fs setacl dirname username rl fs setacl dirname username rlidwka fs listacl dirnameThe first two commands change the permissions on

dirnameto give the userusernameread and list permissions (rl) or full permissions (rlidwka). Thefs listaclcommand shows the directory's current permissions. Usefsrin place offsto recursively apply permissions to all subdirectories as well. Note: on myth as of Oct 2014,fsrhas to be invoked it via its full path/afs/cs/software/bin/fsr. -

Arrays and pointers. The file

arrptr.ccontains a nonsense C program that uses arrays and pointers. Scan the source, then build it, and start it under gdb and set a breakpoint atmain. Run the program. When you hit the breakpoint, step through the first line or two which initializes the variables and stop to take a look around. Try out the gdbxcommand which is used to examine raw memory :(gdb) x/10wd arrxdumps the contents of memory starting at a given address. In the command above, the modifiers/10wdtell gdb to print 10 words (awordis system-speak for 4 bytes) interpreting each word as a decimal integer. Usehelp xto read about other available modifiers. What modifiers would print the first 3 integers in hex?Another key command for your gdb repertoire is

print. The command prints the values of simple variables and much more: use print to evaluate expressions, make function calls, change the values of variables by assigning to them, and so on. Let's use it to experiment with arrays and pointers. The expressions below all refer toarr. First try to figure out what the result of the expression should be, then useprint(shortcutp) in gdb to confirm that your understanding is correct.(gdb) p *arr (gdb) p arr[1] (gdb) p arr[1] = -99 (gdb) p &arr[1] (gdb) p arr + 1 (gdb) p &arr[3] - &arr[1] (gdb) p sizeof(arr) (gdb) p arr = arr + 1The main function initializes

ptrtoarr. If you repeat the above expressions withptrsubstituted forarr, most (but not all) have the same result. The first group evaluate identically, but the last two produce different results forptrthanarr. The stack array and a pointer to it are almost interchangeable, but not entirely. Can you explain those subtle differences and why they exist?Resume execution using the gdb

stepcommand to single-step. The code passesarrandptras arguments tobinky. Step intobinkyand useinfo argsto see values of the two parameters. Sure do look the same... Print various expressions onaandband you'll find they behave identically, even for the last two expressions from above.sizeofreports the same size foraandband assignment is permissible for either. What happens in parameter passing to make this so? Try drawing a picture of the state of memory to shed light on the matter.If you don't understand or can't explain the results you observe, stop here and sort it out with your partner or the TA. Having a solid model of what is happening is an important step toward understanding the similarities and subtle differences between arrays and pointers.

-

Passing pointers by reference. One often-misunderstood aspect of C arrays/pointers is knowing when and why you need to pass a pointer itself by reference and must face off with the dreaded double

**. Consider the functionschop_to_frontandchop_to_backin arrptr.c. First manually trace the code and predict what effect each call will have on the variables in main. Then run under gdb and single-step through the calls using gdb print or x to observe what is happening in memory as you go. How ischop_to_frontsuccessful in making a persistent change? Why ischop_to_backnot successful?Once you understand the fatal flaw in

chop_to_back, correct the function to successfully make the persistent change it attempts. Because C has no pass-by-reference mechanism, you must manually add a level of indirection. Your new version ofchop_to_backcan changebufptr, but notbuffer. Understanding the difference is tricky! Stop and reason it through. Do you see whybufferis not an L-value and how you cannot reassign where it points? (You may find it surprising that the expression&bufferis even legal, but the compiler treats that particular use of&as basically a no-op -- look very carefully at what is printed by gdb for&buffer[0]versus&buffer) Sketching another picture may be illustrative here. -

Memory errors and valgrind. Valgrind is a supremely helpful tool for tracking down memory errors. However, it takes some practice to learn how to interpret a Valgrind report, so that's what this exercise is about. If you haven't already, review the our guide to valgrind written by legendary CS107 TA Nate.

The

buggy.cprograms contains a set of memory errors, a few of which get compiler warnings, but most compile without a care. The buggy program is designed to be invoked with a command-line argument (a number from 1 to 8) that identifies which error to make. For each numbered error N, first peruse the code in buggy.c to see what the error is and then try to predict the consequence of that error. Runbuggy Nwithout Valgrind and see what (if any) symptoms appear during normal execution. Then runbuggy Nunder Valgrind and see what it detects. Read the Valgrind report and see how it identifies the type of error, how many bytes were involved, the size and location of memory at fault (stack/heap/global), and the line of code when the error was detected. How could you use these facts from a Valgrind report to find and fix the root cause of the error?Becoming a skilled user of Valgrind is invaluable to a programmer. We recommend that you run Valgrind early and often during your development cycle. Your strategy should go something like this: run all newly-introduced code under Valgrind, stop at the first error reported, study the report, follow the details to suspicious part of the code, ferret out root cause, resolve the problem, recompile, and re-test to see that this error has gone away. Repeat for any remaining errors. Don't move on until all memory errors are completely resolved. Note that memory leaks don't demand the immediate attention that errors do. Leaks can (and should) be safely ignored until the final phase of polishing a working program.

-

Function pointers. The sort/search functions of the C standard library are written as generics (e.g. using

void*) and require the client to supply callback functions to compare elements. A callback function often only needs simple logic to do its task, but managing the syntax and applying the correct level of indirection is where the trickiness comes in. Use thefnptr.cprogram to practice writing client callback functions in preparation for your current assignment. Start by reading aboutqsortandlfindin our guide to stdlib or in their man pages.The

numbersfunction creates an array of random numbers and sorts it into increasing order. Add a new callback to sort the array in decreasing order instead. Change the code to make two calls toqsortthat sort the first half of the array into increasing order and the back half decreasing.The

stringsfunction reads strings from a file and prints them out. Add code to unique the strings, so that each string is only entered into the array once. You can do this using eitherlfind/lsearchon an unordered array or keep the array in sorted order and take advantage of the fasterbsearch.These exercises are excellent practice for your next assignment where you will be working as a client of

void*interfaces.

Check off with TA

Before you leave, complete your checkoff form and ask your lab TA to approve it so you are properly credited. If you don't complete all the exercises during the lab period, we encourage you to followup and finish the remainder on your own. Try our self-check to reflect on what you've done and how it's going.