Lab sessions Tue Jan 29 to Thu Jan 31

Lab written by Julie Zelenski, with modifications by Nick Troccoli

Learning Goals

During this lab, you will:

- investigate how arrays and pointers work in C

- get further practice with gdb and valgrind

- experiment with code that dynamically allocates memory on the heap

Find an open computer to share with a partner with whom you haven't worked before. Introduce yourself and tell them your thoughts on the best places on campus to get work done.

Get Started

Clone the lab starter code by using the command below. This command creates a lab3 directory containing the project files.

git clone /afs/ir/class/cs107/repos/lab3/shared lab3

Next, pull up the online lab checkoff and have it open in a browser so you can jot things down as you go. Only one checkoff needs to submitted for both you and your partner.

Tip: the GDB and Valgrind guides on the Resources are great references for the various commands and strategies you can use to debug. In particular, the GDB guide has a section on good debugging strategies, including ways to use GDB to fix any issues you encounter. We'd highly recommend reviewing them if you haven't already!

Exercises

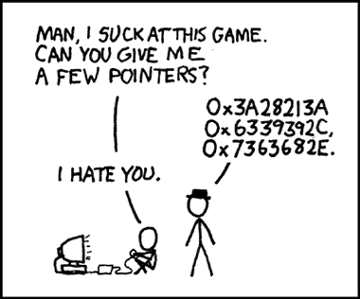

1) GDB: Pointers and Arrays (25 minutes)

First, we'll play around with pointer and array syntax, and how the two are similar and different. To do this, we'll use the provided code.c program, which is a not-terribly-useful program that exhibits various behaviors of arrays and pointers.

- Build the program, start it under

gdb, and set a breakpoint atmain. When you hit the breakpoint, useinfo localsto see the state of the uninitialized stack variables. This command lists the values of all local variables in the current function. Step through the initialization statements and useinfo localsagain. Remember that whengdbreports that execution is at line N, this is before line N has executed. -

The expressions below all refer to the local variable

arr. For each expression, first try to figure out what the result of the expression should be, and then evaluate the expression ingdbto confirm that your understanding is correct.(gdb) p *arr (gdb) p arr[1] (gdb) p &arr[1] (gdb) p *(arr + 2) (gdb) p &arr[3] - &arr[1] (gdb) p sizeof(arr) (gdb) p arr = arr + 1 -

The

mainfunction initializesptrtoarr. The name of a stack array and a pointer to that array are almost interchangeable, but not entirely. Try re-evaluating the above expressions withptrsubstituted forarr. The first five evaluate identically, but the last two produce different results forptrthanarr. What is reported for the size of an array? the size of a pointer? The last one is the trickiest to understand. Why is it allowable to assign toptrbut notarr? - execute

p ptr = ptr - 1to resetptrto its original value. - Use the gdb

stepcommand to advance into the callbinky(arr, ptr).stepis likenext, but instead of executing the entire line and moving to the next line, it steps into the execution of the line. Once insidebinky, useinfo argsto see the values of the two parameters. Print any expression you can think of onaandband they will evaluate to the same result. This includes the last two expressions from above:sizeofreports the same size foraandband assignment is permissible for either. What happens in parameter passing to make this so? Try drawing a picture of the state of memory to shed light on the matter. - Set a breakpoint on

change_charand continue until this breakpoint is hit by executing the GDBccommand (for "continue"). When stopped there in gdb, useinfo args. The arguments shown are from the function call ("frame") forchange_char. The default frame of reference is the currently executing function. - Use

backtraceto show the sequence of function calls that led to where the code is currently executing. You can select a different frame of reference with the gdbframecommand. Frames are numbered starting from 0 for the innermost frame, and the numbers are displayed in the output of thebacktracecommand. Try the commandframe 1to select the frame outsidechange_charand and then useinfo localsto see the state fromwinky. The gdb commandupis shorthand for selecting the frame that is one higher than the current one, anddownis shorthand for selecting the frame that is one lower than the current one. Typeframe 0ordownto return to the line where the debugger is paused. - Step through

change_charand examine the state before and after each line. Useinfo argsto show the inner frame andupandinfo localsto show what's happening in the outer frame. Carefully observe the effect of each assignment statement. - Step through the call to

change_ptrand make the same observations. Which of the assignment statements had a persistent effect inwinky, and which did not? Can you explain why?

If you don't understand or can't explain the results you observe, stop here and discuss them with your labmates and lab leader. Having a solid model of what is going on under the hood is an important step toward understanding the commonalities and subtle differences between arrays and pointers.

2) Code Study: Heap Use (30 minutes)

Next, we'll take a look at code that dynamically allocates memory on the heap using malloc, strdup and realloc. Specifically, we'll look at heap.c, which you can run or trace in gdb, containing two sample functions written for this lab called remove_first_occurrence and join.

The function remove_first_occurrence(text, pattern) returns a string which is a copy of text with the first occurrence of pattern removed. The returned string is heap-allocated and becomes the client's responsibility to free when done.

1 char *remove_first_occurrence(const char *text,

2 const char *pattern) {

3

4 char *found = strstr(text, pattern);

5

6 if (!found) {

7 return strdup(text);

8 }

9

10 int nbefore = found - text;

11 int nremoved = strlen(pattern);

12 char *result = malloc(strlen(text) + 1 - nremoved);

13 assert(result != NULL);

14

15 strncpy(result, text, nbefore);

16 strcpy(result + nbefore, found + nremoved);

17 return result;

18 }

Talk through the following questions with your partner to understand this code. Ask questions about anything confusing!

- What is the purpose of the library function

strstr? What does it return? - Lines 6-8 handle the case where there is no occurrence of

patternintext, i.e. nothing to remove. Why does the function returnstrdup(text)rather than just returningtext? - Line 10 subtracts two pointers. What is the result of subtracting two pointers? Here's a hint: if q = p + 3, then q - p => 3. How does the sizeof(pointee) affect the result of a subtraction?

assertterminates the program if the passed-in expression is false. What is the check on line 13?- After line 15 executes, is the result string null-terminated? Why or why not?

- Your colleague proposes changing line 16 to instead:

strcat(result, found + nremoved)claiming it will operate equivalently. You try it and it even seems to work. Is it equivalent? No, not quite... The code is just "getting lucky". In what way does it (wrongly) depend on the initial contents of newly allocated heap memory? How will the function break when that wrong assumption is not true? - Try running the code; if you run

./heapwith no arguments, it will run a short test of the function, removing "time" from "centimeter".

The function join(strings, strings_count) returns a string which is the concatenation of all strings_count strings in strings. The returned string is heap-allocated and becomes the client's responsibility to free when done. A core function that makes this implementation possible is the realloc function.

1 char *join(char *strings[], int strings_count) {

2 char *result = strdup(strings[0]);

3

4 for (int i = 1; i < strings_count; i++) {

5 result = realloc(result, strlen(result) + strlen(strings[i]) + 1);

6 assert(result != NULL);

7 strcat(result, strings[i]);

8 }

9 return result;

10 }

- At the outset of the loop, the total size needed is not known, so it cannot do the allocation upfront. Instead it makes an initial allocation and enlarges it for each additional string. This resize-as-you-go approach is an idiomatic use case for

realloc. - Is the size argument to

reallocthe number of additional bytes to add to the memory block, or the total number of bytes including any previously allocated part? - The variable

resultis initialized tostrdup(arr[0]). Why does it make a copy instead of just assigningresult = arr[0]? - The

reallocmanual page says the return value fromrealloc(ptr, newsize)may be the same asptr, but also may be different. In the case where it is different,reallochas copied the contents from the old location to the new. The old location is also freed. Change the code to callreallocwithout using its return value (i.e. don't re-assignptr, just drop the result). Re-compile and you should get a warning from the compiler. What error is that warning trying to caution you against? Arealloccall that doesn't catch its return value is never the right call. - Try running the code; if you run

./heapwith one or more arguments, it will join all of the arguments together using thejoinfunction.

3) Code study: calloc (25 minutes)

Finally, we'll study the implementation of calloc, an alternative to the malloc memory-allocating function, to better understand how heap memory allocation works. First, read the manual page for the function (man calloc) and then review the implementation for musl_calloc shown below (taken from musl):

1 void *musl_calloc(size_t nelems, size_t elemsz) {

2 if (nelems && elemsz > SIZE_MAX/nelems) {

3 return NULL;

4 }

5 size_t total = nelems * elemsz;

6 void *p = malloc(total);

7 if (p != NULL) {

8 long *wp;

9 size_t nw = (total + sizeof(*wp) - 1)/sizeof(*wp);

10 for (wp = p; nw != 0; nw--,wp++)

11 *wp = 0;

12 }

13 return p;

14 }

The calloc interface is presented as allocating an array of nelems elements each of size elemsz bytes. It initializes the memory contents to zero, which is the feature that distinguishes calloc from ordinary malloc.

Here are some issues to go through with your partner to understand the operation of this function.

- The

callocinterface as described in terms of arrays is somewhat misleading because there is nothing array-specific to its operation. It simply allocates a region of total sizenelems * elemszbytes. The callcalloc(10, 2)has exactly the same effect ascalloc(4, 5)orcalloc(1, 20)and memory allocated by any of those calls could be used to store a length-20 string or an array of 5 integers, for example. - What are lines 2-4 of the function doing? What would be the effect on the function's operation if these were removed?

- A colleague objects to the use of division on line 2 because division is more expensive than multiplication and it requires an extra check for a zero divisor. They propose changing it to

if (nelems * elemsz > SIZE_MAX), claiming it will operate equivalently and more efficiently. Explain to them why this plan won't work. - Line 7 declares

pto be of typevoid*, which matches the return type ofmalloc. Avoid*pointer is a generic pointer. It stores an address, but makes no claim about the type of the pointee. It is illegal to dereference or do pointer arithmetic on avoid*, since both of these operations depend on the type of the pointer, which is not known in this case. However,void *can be assigned to/from without an explicit cast. - What is the purpose of line 7? What would be the effect on the function's operation if that test were removed and it always proceeded into the loop?

- Line 9 contains the expression

sizeof(*wp). Given thatwpwas declared and not assigned, this looks to dereference an uninitialized pointer! Not to fear, it turns out thatsizeofis evaluated at compile-time by working out the size for an expression from its declared type. Sincewpwas declared as along *, the expression*wpis of typelongwhich on Myth systems has size 8 bytes. The compiler will have transformed it into(total + 8 - 1)/8. Phew! There will be no nasty runtime surprises. - Let's further dig into line 9. It should remind you of code we've seen previously (roundup in lab1). What is the value of

nwfor the callcalloc(20, 4), forcalloc(2, 7), or forcalloc(3, 1)? Aha, this is a rounding operation, as suspected. This calculation is making an assumption about how many bytesmallocwill actually reserve for a given requested size. What is that assumption? (This behavior is not a documented public feature and no client that was a true outsider should assume this, butcallocandmallocwere authored by the same programmer, and thuscallocis being written by someone with firsthand knowledge of themallocinternals and acting as a privileged insider.) - The initialization of the

forloop on line 10 assignswp = p, yetwpandpare not of the same declared type. Why is no typecast required here? Would the function behave any differently if you added the typecastwp = (long *)p? - The increment of the

forloop on line 10 offers a rare glimpse of C's comma operator. You can read more about the comma operator on Wikipedia; the only use you are likely to see in practice is to pack multiple expressions into a loop init or increment. In this case, the increment will both advance the pointer and decrement the count of iterations remaining. - Imagine if line 8 instead declared

char *wpwith no other changes to the code. How would this change the function's behavior? What if the declaration wasint *wp? What if the declaration werevoid *wp? For each, consider how the pointee type affects the operationswp++and*wp = 0. What do you think is the motivation for the author's choice oflong *?

4) Valgrind: Heap Errors (20 minutes)

Last week's lab introduced you to Valgrind. This tool will be increasingly essential as we advance to writing C code with heavy use of pointers and dynamic memory. In particular, Valgrind is great at detecting memory issues relating to dynamic memory, such as writing past what you've allocated, accessing freed memory, freeing memory twice, etc. The buggy.c program has some planted errors that misuse heap memory to let you see how Valgrind handles and reports these errors.

- Review the program in

buggy.cand consider error #1. When the program is invoked as./buggy 1 argument, it will copyargumentinto a heap-allocated space of 8 characters. If the argument is too long, this code will write past the end of the allocated space - a "buffer overflow" (because the write overflows past the end of a buffer). This is similar to errors we've seen in the past about writing past stack memory used to store a string, but now the overflow is happening on the heap. What are the consequences of this error? Let's observe. - Run

./buggy 1 lelandto see that the program runs correctly when the name fits. Now try longer names./buggy 1 stanfordand./buggy 1 lelandstanford. Surprisingly, these also seem to "work", apparently getting lucky when the overrun is still relatively small. Pushing further to./buggy 1 lelandstanfordjunioruniversity, you'll eventually get the crash you expect. - Many crashes have nothing more to say that just "segmentation fault", but this particular crash gives a dump of the program state. This error-reporting is coming from inside the

freefunction of the standard library. The dump is not presented in a particularly user-friendly form, and rather than trying to decipher it, just take it as an indication of a memory problem, for which we will turn to Valgrind for further help. - Try

valgrind ./buggy 1 stanfordand review Valgrind's report to see what help it can offer. Whether the write goes too far by 1 byte or 1000 bytes, Valgrind will helpfully report the error at the moment of transgression. Hooray! - Errors 2, 3, and 4 explore the consequences of other misuses of heap memory. Consider these cases one at a time. Review the code to see what the error is, and then run it (e.g.

./buggy 2). Is there an observable result of the error? Now run it under Valgrind. Take note of the terminology that the Valgrind report uses and how it relates back to the root cause.

Be forewarned that memory errors can be very elusive. A program might crash immediately when the error is made, but the more insidious errors silently destroy something that only shows up much later, making it hard to connect the observed problem with the original cause. The most frustrating errors are those that "get lucky" and cause no observable trouble at all, but lie in wait to surprise you at the most inopportune time. Make a habit of using Valgrind early and often in your development to detect and eradicate memory errors!

5) Valgrind: Memory Leaks (20 minutes)

While not memory errors, memory leaks are another type of issue that Valgrind can help detect. A memory leak is when you allocate memory on the heap, but do not free it. These rarely (if ever) cause crashes, and for this reason we recommend that you do not worry about freeing memory until your program is completely written. Then, you can go back and deallocate your memory as appropriate, ensuring correctness at each step. Memory leaks are an issue, however, because your program should be responsible for cleaning up any memory it allocates but no longer needs. In particular, for larger programs, if you never free any memory and allocate an extremely large amount, you may run out of memory in the heap!

The leaks.c program has some planted memory leaks to let you see how Valgrind handles and reports these leaks.

- Review the program in

leaks.cand consider leak #1. When the program is invoked as./leaks 1, it will allocate 8 bytes on the heap, but then immediately return, causing the program to lose the address of this heap memory. A memory leak! The program terminates fine, however. Let's see how Valgrind can help us detect it. - Try

valgrind ./leaks 1and review Valgrind's report to see what help it can offer. You'll notice that Valgrind reports a "LEAK SUMMARY" at the bottom, as well as a total heap usage summary, which shows what memory was still in use at exit (that should have been freed). You can also see the number of reported allocations and frees to not line up, indicating a leak. Helpful! - For even more memory leak information, make sure to use the

--leak-check=fulland--show-leak-kinds=allflags when you run valgrind. Run it again like this:valgrind --leak-check=full --show-leak-kinds=all ./leaks 1. This shows even more information, including where the leaked memory was originally allocated! We recommend always running with these flags to get the most information. Make sure to put these flags before the command to run your actual program. Specifically, the following is not equivalent:valgrind ./leaks 1 --leak-check=full --show-leak-kinds=all, as this passes these flags to your program, instead of valgrind! - What is the difference between "definitely lost", "indirectly lost", etc.? Check out our Valgrind guide for an overview.

- Leaks 2 and 3 explore other possible manifestations of memory leaks. Consider these cases one at a time. Review the code to see what the error is, and then run it (e.g.

./leaks 2). Notice how the program always runs fine. Now run it under Valgrind. Take note of the terminology that the Valgrind report uses and how it relates back to the root cause. Note that leaks do not only have to come from memory you allocate usingmalloc. For example, functions likestrdupallocate memory that it is the caller's responsibility to free! - the total heap usage includes more than just your explicit allocations. For example, other functions, like

strdup, may allocate/free memory internally as well!

[Optional] Challenge Problem

Finished with lab and itching to further exercise your memory skills? Check out our challenge problem!

Check off with TA

At the end of the lab period, submit the checkoff form and ask your lab TA to approve your submission so you are properly credited for your work. It's okay if you don't completely finish all of the exercises during lab; your sincere participation for the full lab period is sufficient for credit. However, we highly encourage you to finish on your own whatever is need to solidify your knowledge. Also take a chance to reflect on what you got what from this lab and whether you feel ready for what comes next! The takeaways from lab3 should be continued development of your gdb and Valgrind skills, as well as your skills reading and writing code with heavy use of pointers. Arrays and pointers are ubiquitous in C and a good understanding of them is essential. Here are some questions to verify your understanding and get you thinking further about these concepts:

- If

ptris declared as anchar *, what is the effect ofptr++? What ifptris declared as aint *? - Although

&applied to the name of a stack-allocated array (e.g.&buffer) is a legal expression and has a defined meaning, it isn't really sensible. Explain why such use may indicate an error/misunderstanding on the part of the programmer. - The argument to malloc is

size_t(unsigned). Consider the erroneous callmalloc(-1), which seems to make no sense at all. The call compiles with nary a complaint -- why is it "ok"? What happens when it executes? - What is the purpose of the

reallocfunction? What happens if you attempt to realloc a non-malloc-ed pointer, such as a string constant? - What is the difference between a memory error and a memory leak?