Friday, January 7, 2022

Computer Systems

Winter 2022

Stanford University

Computer Science Department

Reading: Reader: Bits and Bytes, Textbook: Chapter

2.2

Lecturer: Chris Gregg

CS 107

Lecture 2: Integer

Representations

Today's Topics

•Logistics

•Assign0 —Due Monday

•Labs start Tuesday

•Office hours in full coverage

•Reading: Reader: Bits and Bytes, Textbook: Chapter 2.2 (very mathy…)

•Integer Representations

•Unsigned numbers

•Signed numbers

•two's complement

•Signed vs Unsigned numbers

•Casting in C

•Signed and unsigned comparisons

•The sizeof operator

•Min and Max integer values

•Truncating integers

•two's complement overflow

Information Storage

In C, everything can be thought of as a block of 8 bits

Information Storage

In C, everything can be thought of as a block of 8 bits

called a "byte"

Information Storage

We will discuss manipulating bytes on a bit-by-bit level, but we won't be

able to consider an individual bit on its own.

In a computer, the memory system is simply a large array of bytes (sound

familiar, from CS106B?)

728314 99 -6 3 45 11

200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209

0xc8 0xc9 0xca 0xcb 0xcc 0xcd 0xce 0xcf 0xd0 0xd1

values (bytes):

address (decimal):

address (hex):

Each address (a pointer!) represents the next byte in memory.

E.g., address 0 is a byte, then address 1 is the next full byte, etc.

Again: you can't address a bit. You must address at the byte level.

Byte Range

Because a byte is made up of 8 bits, we can represent the range of a byte

as follows:

00000000 to 11111111

This range is 0 to 255 in decimal.

But, neither binary nor decimal is particularly convenient to write out bytes

(binary is too long, and decimal isn't numerically friendly for byte

representation)

So, we use "hexadecimal," (base 16).

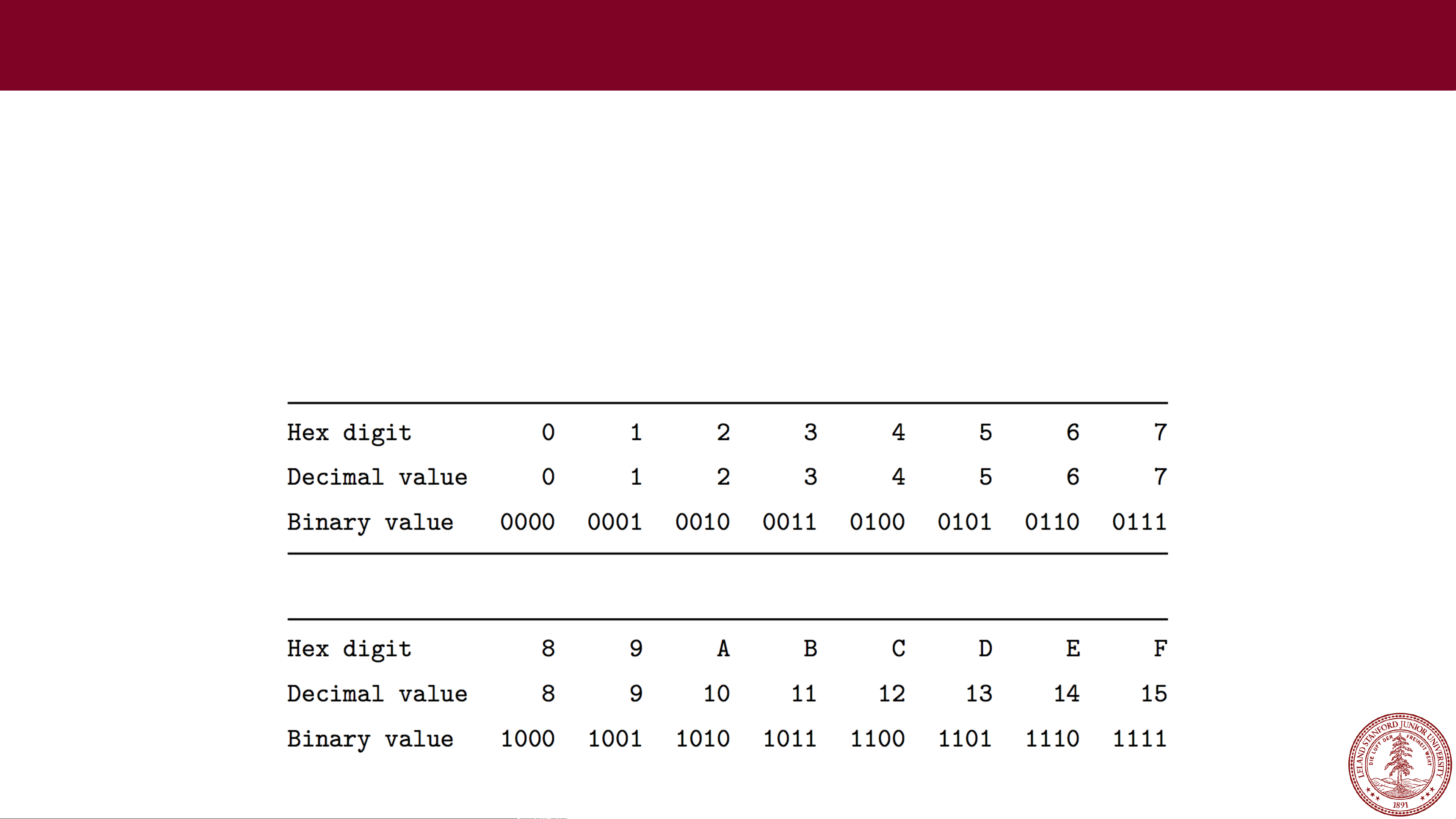

Hexadecimal

Hexadecimal has 16 digits, so we augment our normal 0-9 digits with six

more digits: A, B, C, D, E, and F.

Figure 2.2 in the textbook shows the hex digits and their binary and

decimal values:

Hexadecimal

•In C, we write a hexadecimal with a starting 0x. So, you will see

numbers such as 0xfa1d37b, which means that it is a hex number.

•You should memorize the binary representations for each hex digit. One

trick is to memorize A (1010), C (1100), and F (1111), and the others

are easy to figure out.

•Let's practice some hex to binary and binary to hex conversions:

Convert: 0x173A4C to binary.

0x173A4C is binary

0b000101110011101001001100

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Hexadecimal

Convert: 0b1111001010110110110011 to hexadecimal.

0b1111001010110110110011

is hexadecimal 3CADB3

(start from the right)

Decimal to Hexadecimal

To convert from decimal to hexadecimal, you need to repeatedly divide

the number in question by 16, and the remainders make up the digits of

the hex number:

Hexidecimal to Decimal

To convert from hexadecimal to decimal, multiply each of the hexadecimal

digits by the appropriate power of 16:

Let the computer do it!

Honestly, hex to decimal and vice versa are easy to let the

computer handle. You can either use a search engine (Google

does this automatically), or you can use a python one-liner:

Let the computer do it!

You can also use Python to convert to and from binary:

(but you should memorize this as it is easy and you will use it

frequently)

Integer Representations

Integer Representations

The C language has two different ways to represent numbers, unsigned and

signed:

unsigned: can only represent non-negative numbers

signed: can represent negative, zero, and positive numbers

We are going to talk about these representations, and also about what happens

when we expand or shrink an encoded integer to fit into a different type (e.g., int

to long)

Unsigned Integers

For positive (unsigned) integers, there is a 1-to-1 relationship between the

decimal representation of a number and its binary representation. If you have a

4-bit number, there are 16 possible combinations, and the unsigned numbers go

from 0 to 15:

0b0000 = 0 0b0001 = 1 0b0010 = 2 0b0011 = 3

0b0100 = 4 0b0101 = 5 0b0110 = 6 0b0111 = 7

0b1000 = 8 0b1001 = 9 0b1010 = 10 0b1011 = 11

0b1100 = 12 0b1101 = 13 0b1110 = 14 0b1111 = 15

The range of an unsigned number is 0 → 2w- 1, where wis the number of bits

in our integer. For example, a 32-bit int can represent numbers from 0 to

232 - 1, or 0 to 4,294,967,295.

Signed Integers: How do we represent them?

What if we want to represent negative numbers? We have choices!

One way we could encode a negative number is simply to designate some bit as

a "sign" bit, and then interpret the rest of the number as a regular binary number

and then apply the sign. For instance, for a four-bit number:

0 001 = 1

0 010 = 2

0 011 = 3

0 100 = 4

0 101 = 5

0 110 = 6

0 111 = 7

1 001 = -1

1 010 = -2

1 011 = -3

1 100 = -4

1 101 = -5

1 110 = -6

1 111 = -7

This might be okay...but we've only represented 14 of our 16 available numbers...

Signed Integers: How do we represent them?

0 001 = 1

0 010 = 2

0 011 = 3

0 100 = 4

0 101 = 5

0 110 = 6

0 111 = 7

1 001 = -1

1 010 = -2

1 011 = -3

1 100 = -4

1 101 = -5

1 110 = -6

1 111 = -7

What about 0 000 and 1 000? What should

they represent?

Well...this is a bit tricky!

Signed Integers: How do we represent them?

0 001 = 1

0 010 = 2

0 011 = 3

0 100 = 4

0 101 = 5

0 110 = 6

0 111 = 7

1 001 = -1

1 010 = -2

1 011 = -3

1 100 = -4

1 101 = -5

1 110 = -6

1 111 = -7 0 000 1 000Let's look at the bit patterns:

What about 0 000 and 1 000? What should

they represent?

Well...this is a bit tricky!

Should we make the 0 000 just represent decimal 0? What about 1 000? We

could make it 0 as well, or maybe -8, or maybe even 8, but none of the choices

are nice.

Signed Integers: How do we represent them?

0 001 = 1

0 010 = 2

0 011 = 3

0 100 = 4

0 101 = 5

0 110 = 6

0 111 = 7

1 001 = -1

1 010 = -2

1 011 = -3

1 100 = -4

1 101 = -5

1 110 = -6

1 111 = -7 0 000 1 000Let's look at the bit patterns:

Should we make the 0 000 just represent decimal 0? What about 1 000? We

could make it 0 as well, or maybe -8, or maybe even 8, but none of the choices

are nice.

What about 0 000 and 1 000? What should

they represent?

Well...this is a bit tricky!

Fine. Let's just make 0 000 to be equal to decimal 0. How does arithmetic

work?

Well…to add two numbers, you need to know the sign, then you might have to

subtract (borrow and carry, etc.), and the sign might change…this is going to

get ugly!

Signed Integers: How do we represent them?

Signed Integers: How do we represent them?

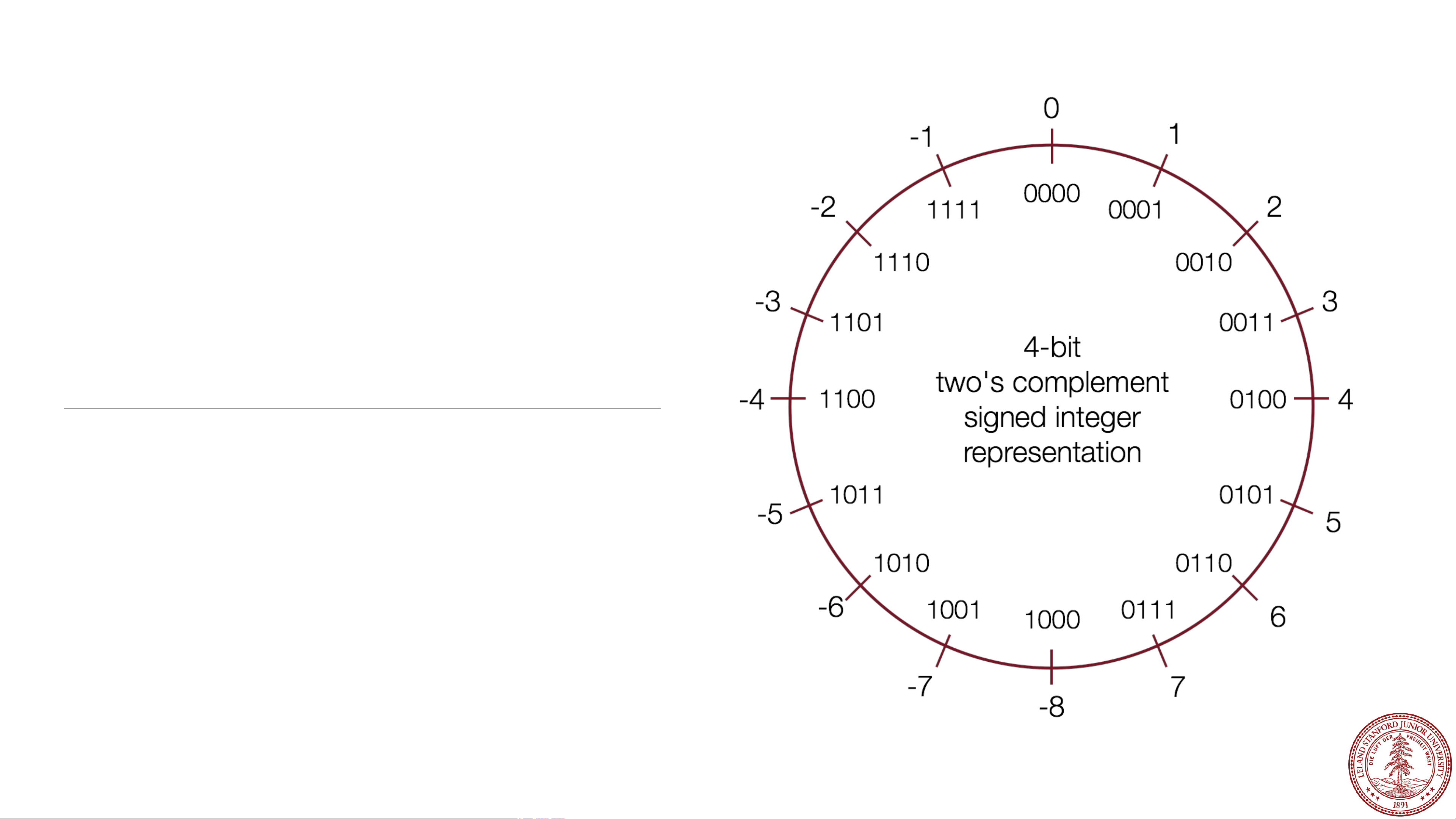

Behold: the "two's complement" circle:

In the early days of computing*, two's

complement was determined to be an

excellent way to store binary numbers.

In two's complement notation, positive

numbers are represented as

themselves (phew), and negative

numbers are represented as the two's

complement of themselves (definition

to follow).

This leads to some amazing arithmetic

properties!

*John von Neumann suggested it in 1945, for the EDVAC

computer.

Two's Complement

In practice, a negative number in two's complement is obtained by

inverting all the bits of its positive counterpart*, and then adding 1.

*Inverting all the bits of a number is its "one's complement"

Definition:

A two's-complement number system encodes positive

and negative numbers in a binary number

representation. The weight of each bit is a power of two,

except for the most significant bit, whose weight is the

negative of the corresponding power of two.

B2Twmeans "Binary to Two's complement function"

Two's Complement

In practice, a negative number in two's

complement is obtained by inverting all

the bits of its positive counterpart*, and

then adding 1, or: x = ~x + 1

*Inverting all the bits of a number is its "one's complement"

Example: The number 2 is represented as normal in

binary: 0010

-2 is represented by inverting the bits, and adding 1:

0010 ☞1101

1101

+ 1

1110

Two's Complement

Trick: to convert a positive number to

its negative in two's complement, start

from the right of the number, and write

down all the digits until you get to a 1.

Then invert the rest of the digits:

*Inverting all the bits of a number is its "one's complement"

Example: The number 2 is represented as normal in

binary: 0010

Going from the right, write down numbers until you

get to a 1:

10

Then invert the rest of the digits:

1110

Two's Complement

To convert a negative number to a

positive number, perform the same

steps!

Example: The number -5 is represented in two's

complements as: 1011

5 is represented by inverting the bits, and adding 1:

1011 ☞0100

0100

+ 1

0101

Shortcut: start from the right, and write down

numbers until you get to a 1:

1

Now invert all the rest of the digits:

0101

Two's Complement: Neat Properties

There are a number of useful

properties associated with two's

complement numbers:

1. There is only one zero (yay!)

2. The highest order bit (left-most) is 1

for negative, 0 for positive (so it is

easy to tell if a number is negative)

3. Adding two numbers is

just…adding!

Example:

2 + -5 = -3

0010 ☞2

+1011 ☞-5

1101 ☞-3 decimal (wow!)

Two's Complement: Neat Properties

More useful properties:

4. Subtracting two numbers is simply

performing the two's complement

on one of them and then adding.

Example:

4 - 5 = -1

0100 ☞4, 0101 ☞5

Find the two's complement of 5: 1011

add:

0100 ☞4

+1011 ☞-5

1111 ☞-1 decimal

Two's Complement: Neat Properties

More useful properties:

5. Multiplication of two's complement

works just by multiplying (throw

away overflow digits).

Example: -2 * -3 = 6

1110 ☞-2

x1101 ☞-3

1110

0000

1110

+1110

10110110 ☞6

Two's Complement: Powers of two remain!

From the definition of a two's

complement number, we can see that we

are still dealing with bits being equal to

their powers-of-two place: there isn't

anything magical about the placement of

the bits:

-5 = 1 0 1 1

(1 * -23) + (0 * 22) + (1 * 21) + (1 * 20)

Practice

Convert the following 4-bit numbers

from positive to negative, or from

negative to positive using two's

complement notation:

a. -4 (1100) ☞

b. 7 (0111) ☞

c. 3 (0011) ☞

d. -8 (1000) ☞

Practice

Convert the following 4-bit numbers

from positive to negative, or from

negative to positive using two's

complement notation:

a. -4 (1100) ☞

b. 7 (0111) ☞

c. 3 (0011) ☞

d. -8 (1000) ☞

0100

1001

1101

1000 (?! If you look at

the chart, +8 cannot be represented

in two's complement with 4 bits!)

Practice

Convert the following 8-bit numbers

from positive to negative, or from

negative to positive using two's

complement notation:

a. -4 (11111100) ☞

b. 27 (00011011) ☞

c. -127 (10000001) ☞

d. 1 (00000001) ☞

00000100

11100101

01111111

11111111

Casting Between Signed and Unsigned

Converting between two numbers in C can happen explicitly (using a

parenthesized cast), or implicitly (without a cast):

int tx, ty;

unsigned ux, uy;

…

tx = (int) ux;

uy = (unsigned) ty;

1

2

3

4

5

int tx, ty;

unsigned ux, uy;

…

tx = ux; // cast to signed

uy = ty; // cast to unsigned

1

2

3

4

5

explicit implicit

When casting: the underlying bits do not change, so there isn't any

conversion going on, except that the variable is treated as the type that it is.

You cannot convert a signed number to its unsigned counterpart using a

cast!

Casting Between Signed and Unsigned

// test_cast.c

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main() {

int v = -12345;

unsigned int uv = (unsigned int) v;

printf("v = %d, uv = %u\n",v,uv);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

$ ./test_cast

v = -12345, uv = 4294954951

When casting: the underlying bits do not change, so there isn't any

conversion going on, except that the variable is treated as the type that it is.

You cannot convert a signed number to its unsigned counterpart using a

cast!

Casting Between Signed and Unsigned

int x = -1;

unsigned u = 3000000000; // 3 billion

printf("x = %u = %d\n", x, x);

printf("u = %u = %d\n", u, u);

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ ./test_printf

x = 4294967295 = -1

u = 3000000000 = -1294967296

printf has three 32-bit integer representations:

%d : signed 32-bit int

%u : unsigned 32-bit int

%x : hex 32-bit int

As long as the value is a 32-bit type, printf will treat it according to the

formatter it is applying:

Signed vs Unsigned Number Wheels

Comparison between signed and unsigned

integers

When a C expression has combinations of signed and unsigned variables,

you need to be careful!

If an operation is performed that has both a signed and an unsigned value,

C implicitly casts the signed argument to unsigned and performs the

operation assuming both numbers are non-negative. Let's take a look…

Expression Type Evaluation

0 == 0U

-1 < 0

-1 < 0U

2147483647 > -2147483647 - 1

2147483647U > -2147483647 - 1

2147483647 > (int)2147483648U

-1 > -2

(unsigned)-1 > -2

Comparison between signed and unsigned

integers

When a C expression has combinations of signed and unsigned variables,

you need to be careful!

If an operation is performed that has both a signed and an unsigned value,

C implicitly casts the signed argument to unsigned and performs the

operation assuming both numbers are non-negative. Let's take a look…

Expression Type Evaluation

0 == 0U Unsigned 1

-1 < 0 Signed 1

-1 < 0U Unsigned 0

2147483647 > -2147483647 - 1 Signed 1

2147483647U > -2147483647 - 1 Unsigned 0

2147483647 > (int)2147483648U Signed 1

-1 > -2 Signed 1

(unsigned)-1 > -2 Unsigned 1

Comparison between signed and unsigned

integers

Let's try some more…a bit more abstractly.

int s1, s2, s3, s4;

unsigned int u1, u2, u3, u4;

Which many of the following

statements are true? (assume that

variables are set to values that place

them in the spots shown)

s3 > u3

u2 > u4

s2 > s4

s1 > s2

u1 > u2

s1 > u3

Comparison between signed and unsigned

integers

Let's try some more…a bit more abstractly.

int s1, s2, s3, s4;

unsigned int u1, u2, u3, u4;

Which many of the following

statements are true? (assume that

variables are set to values that place

them in the spots shown)

s3 > u3 : true

u2 > u4 : true

s2 > s4 : false

s1 > s2 : true

u1 > u2 : true

s1 > u3 : true

The sizeof Operator

As we have seen, integer types are limited by the number of bits they hold. On

the 64-bit myth machines, we can use the sizeof operator to find how many

bytes each type uses:

int main() {

printf("sizeof(char): %d\n", (int) sizeof(char));

printf("sizeof(short): %d\n", (int) sizeof(short));

printf("sizeof(int): %d\n", (int) sizeof(int));

printf("sizeof(unsigned int): %d\n", (int) sizeof(unsigned int));

printf("sizeof(long): %d\n", (int) sizeof(long));

printf("sizeof(long long): %d\n", (int) sizeof(long long));

printf("sizeof(size_t): %d\n", (int) sizeof(size_t));

printf("sizeof(void *): %d\n", (int) sizeof(void *));

return 0;

}

$ ./sizeof

sizeof(char): 1

sizeof(short): 2

sizeof(int): 4

sizeof(unsigned int): 4

sizeof(long): 8

sizeof(long long): 8

sizeof(size_t): 8

sizeof(void *): 8

Type Width in bytes Width in bits

char 1 8

short 216

int 432

long 864

void * 8 64

MIN and MAX values for integers

Because we now know how bit patterns for integers works, we can figure out

the maximum and minimum values, designated by INT_MAX, UINT_MAX,

INT_MIN, (etc.), which are defined in limits.h

Type Width

(bytes)

Width

(bits) Min in hex (name) Max in hex (name)

char 1 8 80 (CHAR_MIN) 7F (CHAR_MAX)

unsigned char 1 8 0 FF (UCHAR_MAX)

short 216 8000 (SHRT_MIN) 7FFF (SHRT_MAX)

unsigned short 216 0 FFFF (USHRT_MAX)

int 432 80000000 (INT_MIN) 7FFFFFFF (INT_MAX)

unsigned int 432 0FFFFFFFF (UINT_MAX)

long 864 8000000000000000 (LONG_MIN) 7FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF (LONG_MAX)

unsigned long 864 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF (ULONG_MAX)

Expanding the bit representation of a number

Sometimes we want to convert between two integers having different sizes.

E.g., a short to an int, or an int to a long.

We might not be able to convert from a bigger data type to a smaller data

type, but we do want to always be able to convert from a smaller data type

to a bigger data type.

This is easy for unsigned values: simply add leading zeros to the

representation (called "zero extension").

unsigned short s = 4;

// short is a 16-bit format, so s = 0000 0000 0000 0100b

unsigned int i = s;

// conversion to 32-bit int, so i = 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100b

Expanding the bit representation of a number

For signed values, we want the number to remain the same, just with more

bits. In this case, we perform a "sign extension" by repeating the sign of the

value for the new digits. E.g.,

short s = 4;

// short is a 16-bit format, so s = 0000 0000 0000 0100b

int i = s;

// conversion to 32-bit int, so i = 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100b

—or —

short s = -4;

// short is a 16-bit format, so s = 1111 1111 1111 1100b

int i = s;

// conversion to 32-bit int, so i = 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1100b

Sign-extension Example

// show_bytes() defined on pg. 45, Bryant and O'Halloran

int main() {

short sx = -12345; // -12345

unsigned short usx = sx; // 53191

int x = sx; // -12345

unsigned ux = usx; // 53191

printf("sx = %d:\t", sx);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &sx, sizeof(short));

printf("usx = %u:\t", usx);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &usx, sizeof(unsigned short));

printf("x = %d:\t", x);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &x, sizeof(int));

printf("ux = %u:\t", ux);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &ux, sizeof(unsigned));

return 0;

}

$ ./sign_extension

sx = -12345: c7 cf

usx = 53191: c7 cf

x = -12345: c7 cf ff ff

ux = 53191: c7 cf 00 00

(careful: this was printed

on the little-endian myth

machines!)

Back to right shift: arithmetic -vs- logical

Recall that the right-shift (>>)

operator behaves differently for

unsigned and signed numbers:

•Unsigned numbers are

logically-right shifted (by

shifting in 0s, always)

•Signed numbers are

arithmetically-right shifted (by

shifting in the sign bit)

// show_bytes() defined on pg. 45, Bryant and O'Halloran

int main() {

int a = 1048576;

int a_rs8 = a >> 8;

int b = -1048576;

int b_rs8 = b >> 8;

printf("a = %d:\t", a);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &a, sizeof(int));

printf("a >> 8 = %d:\t", a_rs8);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &a_rs8, sizeof(int));

printf("b = %d:\t", b);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &b, sizeof(int));

printf("b >> 8 = %d:\t", b_rs8);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &b_rs8, sizeof(int));

return 0;

}

$ ./right_shift

a = 1048576: 00 00 10 00

a >> 8 = 4096: 00 10 00 00

b = -1048576: 00 00 f0 ff

b >> 8 = -4096: 00 f0 ff ff

(run on a little-endian machine)

Truncating Numbers: Signed

What if we want to reduce the

number of bits that a number

holds? E.g.

int x = 53191;

short sx = (short) x;

int y = sx;

What happens here? Let's look at the bits in x (a 32-bit int), 53191:

0000 0000 0000 0000 1100 1111 1100 0111

When we cast x to a short, it only has 16-bits, and C truncates the

number:

1100 1111 1100 0111

What is this number in decimal? Well, it must be negative (b/c of the initial

1), and it is -12345.

Truncating Numbers: Signed

What if we want to reduce the

number of bits that a number

holds? E.g.

int x = 53191; // 53191

short sx = (short) x; // -12345

int y = sx;

This is a form of overflow! We have altered the value of the number.

Be careful!

We don't have enough bits to store the int in the short for the value we

have in the int, so the strange values occur.

What is y above? We are converting a short to an int, so we sign-extend,

and we get -12345!

1100 1111 1100 0111 becomes

Play around here: http://www.convertforfree.com/twos-complement-calculator/

1111 1111 1111 1111 1100 1111 1100 0111

Truncating Numbers: Signed

If the number does fit into the

smaller representation in the

current form, it will convert just

fine.

int x = -3; // -3

short sx = (short) -3; // -3

int y = sx; // -3

x: 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1101 becomes

Play around here: http://www.convertforfree.com/twos-complement-calculator/

sx: 1111 1111 1111 1101

Truncating Numbers: Unsigned

We can also lose information

with unsigned numbers:

unsigned int x = 128000;

unsigned short sx = (short) x;

unsigned int y = sx;

Bit representation for x = 128000 (32-bit unsigned int):

0000 0000 0000 0001 1111 0100 0000 0000

Truncated unsigned short sx:

1111 0100 0000 0000

which equals 62464 decimal.

Converting back to an unsigned int, y = 62464

Overflow in Unsigned Addition

When integer operations overflow in C, the runtime does not produce an error:

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<limits.h> // for UINT_MAX

int main() {

unsigned int a = UINT_MAX;

unsigned int b = 1;

unsigned int c = a + b;

printf("a = %u\n",a);

printf("b = %u\n",b);

printf("a + b = %u\n",c);

return 0;

}

$ ./unsigned_overflow

a = 4294967295

b = 1

a + b = 0

Technically, unsigned integers in C don't

overflow, they just wrap. You need to be

aware of the size of your numbers. Here is

one way to test if an addition will fail:

// for addition

#include <limits.h>

unsigned int a = <something>;

unsigned int x = <something>;

if (a > UINT_MAX - x) /* `a + x` would overflow */;

Overflow in Signed Addition

Signed overflow wraps around to the negative numbers:

YouTube fell into this trap —their view counter was a signed, 32-bit int. They

fixed it after it was noticed, but for a while, the view count for Gangnam Style

(the first video with over INT_MAX number of views) was negative.

Overflow in Signed Addition

Signed overflow wraps around to the negative numbers.

$ ./signed_overflow

a = 2147483647

b = 1

a + b = -2147483648

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<limits.h> // for INT_MAX

int main() {

int a = INT_MAX;

int b = 1;

int c = a + b;

printf("a = %d\n",a);

printf("b = %d\n",b);

printf("a + b = %d\n",c);

return 0;

}

Technically, signed integers in C produce

undefined behavior when they overflow. On

two's complement machines (virtually all

machines these days), it does overflow

predictably. You can test to see if your addition

will be correct:

// for addition

#include <limits.h>

int a = <something>;

int x = <something>;

if ((x > 0) && (a > INT_MAX - x)) /* `a + x` would overflow */;

if ((x < 0) && (a < INT_MIN - x)) /* `a + x` would underflow */;

References and Advanced Reading

•References:

•Two's complement calculator: http://www.convertforfree.com/twos-complement-

calculator/

•Wikipedia on Two's complement:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two%27s_complement

•The sizeof operator: http://www.geeksforgeeks.org/sizeof-operator-c/

•Advanced Reading:

•Signed overflow: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/16056758/c-c-unsigned-

integer-overflow

•Integer overflow in C: https://www.gnu.org/software/autoconf/manual/autoconf-

2.62/html_node/Integer-Overflow.html

•https://stackoverflow.com/questions/34885966/when-an-int-is-cast-to-a-short-and-

truncated-how-is-the-new-value-determined

01

2

3

4

-1

-2

-3

-4

7

6

5

-7

-6

-5

-8

0000 0001

0010

0011

0100

0101

0110

0111

1111

1110

1101

1100

1011

1010

1001 1000

4-bit

two's complement

signed integer

representation

01

2

3

4

15

14

13

12

7

6

5

9

10

11

8

0000 0001

0010

0011

0100

0101

0110

0111

1111

1110

1101

1100

1011

1010

1001 1000

4-bit

unsigned integer

representation