Monday, January 10, 2022

Computer Systems

Winter 2022

Stanford University

Computer Science Department

Reading: Reader: Number Formats Used in CS 107

and Bits and BytesTextbook: Chapter 2.1

Lecturer: Chris Gregg

CS 107

Lecture 3: Bits

and Bytes

Logistics

•Labs start Tuesday -- you will want to watch Monday's lecture before

your lab.

•Assign0 Due on Monday at 11:59pm

•Assign1 Released today

Today's Topics

•More on extending the bit representation of numbers

•Truncating numbers

•Data Sizes

•Addressing and Byte Ordering

•Boolean Algebra

Expanding the bit representation of a number

Sometimes we want to convert between two integers having different sizes.

E.g., a short to an int, or an int to a long.

We might not be able to convert from a bigger data type to a smaller data

type, but we do want to always be able to convert from a smaller data type

to a bigger data type.

This is easy for unsigned values: simply add leading zeros to the

representation (called "zero extension").

unsigned short s = 4;

// short is a 16-bit format, so s = 0000 0000 0000 0100b

unsigned int i = s;

// conversion to 32-bit int, so i = 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100b

Expanding the bit representation of a number

For signed values, we want the number to remain the same, just with more

bits. In this case, we perform a "sign extension" by repeating the sign of the

value for the new digits. E.g.,

short s = 4;

// short is a 16-bit format, so s = 0000 0000 0000 0100b

int i = s;

// conversion to 32-bit int, so i = 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100b

—or —

short s = -4;

// short is a 16-bit format, so s = 1111 1111 1111 1100b

int i = s;

// conversion to 32-bit int, so i = 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1100b

Sign-extension Example

// show_bytes() defined on pg. 45, Bryant and O'Halloran

int main() {

short sx = -12345; // -12345

unsigned short usx = sx; // 53191

int x = sx; // -12345

unsigned ux = usx; // 53191

printf("sx = %d:\t", sx);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &sx, sizeof(short));

printf("usx = %u:\t", usx);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &usx, sizeof(unsigned short));

printf("x = %d:\t", x);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &x, sizeof(int));

printf("ux = %u:\t", ux);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &ux, sizeof(unsigned));

return 0;

}

$ ./sign_extension

sx = -12345: c7 cf

usx = 53191: c7 cf

x = -12345: c7 cf ff ff

ux = 53191: c7 cf 00 00

(careful: this was printed

on the little-endian myth

machines!)

Back to right shift: arithmetic -vs- logical

// show_bytes() defined on pg. 45, Bryant and O'Halloran

int main() {

int a = 1048576;

int a_rs8 = a >> 8;

int b = -1048576;

int b_rs8 = b >> 8;

printf("a = %d:\t", a);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &a, sizeof(int));

printf("a >> 8 = %d:\t", a_rs8);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &a_rs8, sizeof(int));

printf("b = %d:\t", b);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &b, sizeof(int));

printf("b >> 8 = %d:\t", b_rs8);

show_bytes((byte_pointer) &b_rs8, sizeof(int));

return 0;

}

$ ./right_shift

a = 1048576: 00 00 10 00

a >> 8 = 4096: 00 10 00 00

b = -1048576: 00 00 f0 ff

b >> 8 = -4096: 00 f0 ff ff

(run on a little-endian machine)

The right-shift (>>) operator

behaves differently for unsigned

and signed numbers:

•Unsigned numbers are

logically-right shifted (by

shifting in 0s, always)

•Signed numbers are

arithmetically-right shifted (by

shifting in the sign bit)

Truncating Numbers: Signed

What if we want to reduce the

number of bits that a number

holds? E.g.

int x = 53191;

short sx = (short) x;

int y = sx;

What happens here? Let's look at the bits in x (a 32-bit int), 53191:

0000 0000 0000 0000 1100 1111 1100 0111

When we cast x to a short, it only has 16-bits, and C truncates the

number:

1100 1111 1100 0111

What is this number in decimal? Well, it must be negative (b/c of the initial

1), and it is -12345.

Truncating Numbers: Signed

What if we want to reduce the

number of bits that a number

holds? E.g.

int x = 53191; // 53191

short sx = (short) x; // -12345

int y = sx;

This is a form of overflow! We have altered the value of the number.

Be careful!

We don't have enough bits to store the int in the short for the value we

have in the int, so the strange values occur.

What is y above? We are converting a short to an int, so we sign-extend,

and we get -12345!

1100 1111 1100 0111 becomes

Play around here: http://www.convertforfree.com/twos-complement-calculator/

1111 1111 1111 1111 1100 1111 1100 0111

Truncating Numbers: Signed

If the number does fit into the

smaller representation in the

current form, it will convert just

fine.

int x = -3; // -3

short sx = (short) -3; // -3

int y = sx; // -3

x: 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1101 becomes

Play around here: http://www.convertforfree.com/twos-complement-calculator/

sx: 1111 1111 1111 1101

Truncating Numbers: Unsigned

We can also lose information

with unsigned numbers:

unsigned int x = 128000;

unsigned short sx = (short) x;

unsigned int y = sx;

Bit representation for x = 128000 (32-bit unsigned int):

0000 0000 0000 0001 1111 0100 0000 0000

Truncated unsigned short sx:

1111 0100 0000 0000

which equals 62464 decimal.

Converting back to an unsigned int, y = 62464

Overflow in Unsigned Addition

When integer operations overflow in C, the runtime does not produce an error:

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<limits.h> // for UINT_MAX

int main() {

unsigned int a = UINT_MAX;

unsigned int b = 1;

unsigned int c = a + b;

printf("a = %u\n",a);

printf("b = %u\n",b);

printf("a + b = %u\n",c);

return 0;

}

$ ./unsigned_overflow

a = 4294967295

b = 1

a + b = 0

Technically, unsigned integers in C don't

overflow, they just wrap. You need to be

aware of the size of your numbers. Here is

one way to test if an addition will fail:

// for addition

#include <limits.h>

unsigned int a = <something>;

unsigned int x = <something>;

if (a > UINT_MAX - x) /* `a + x` would overflow */;

Overflow in Signed Addition

Signed overflow wraps around to the negative numbers:

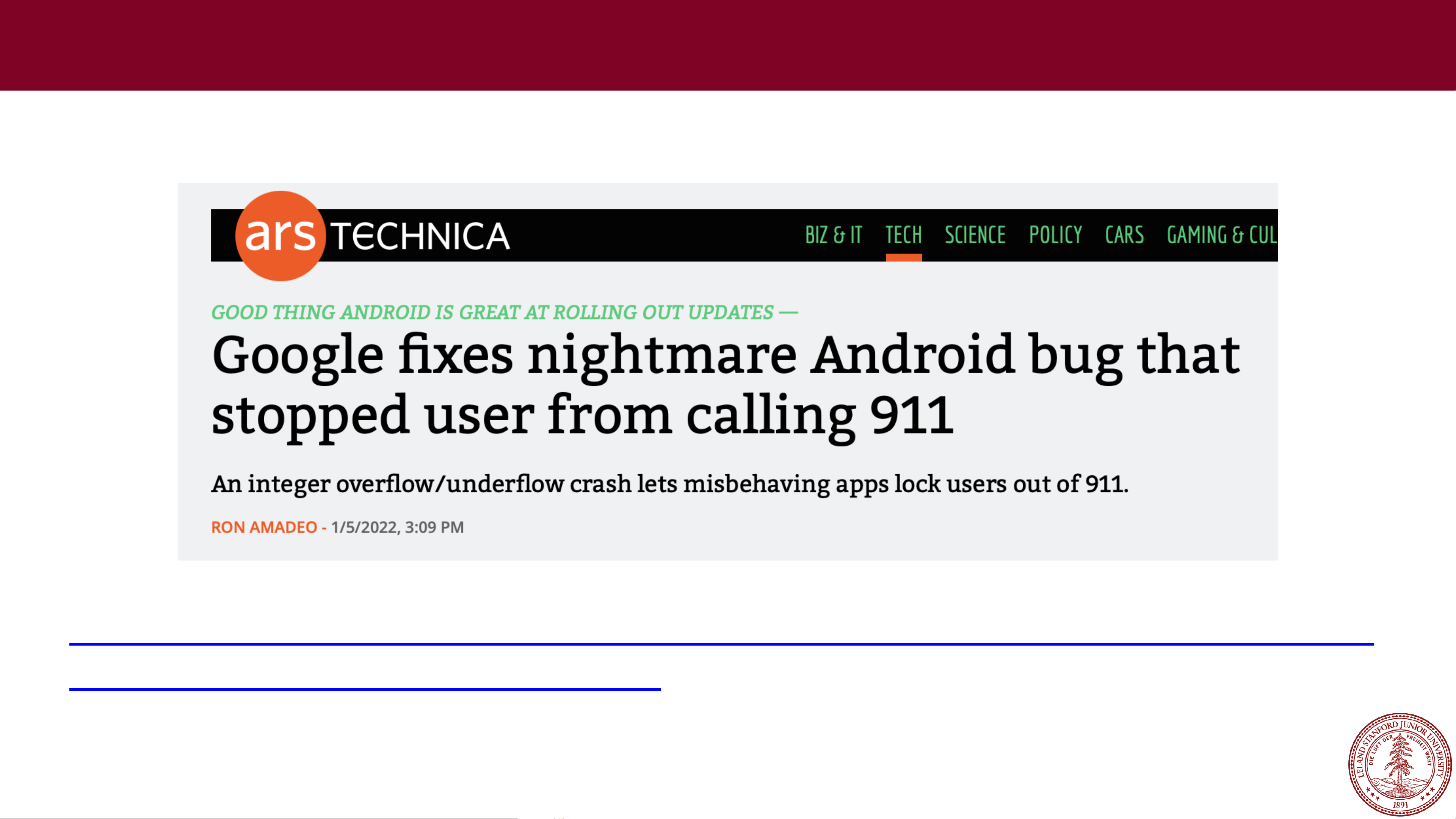

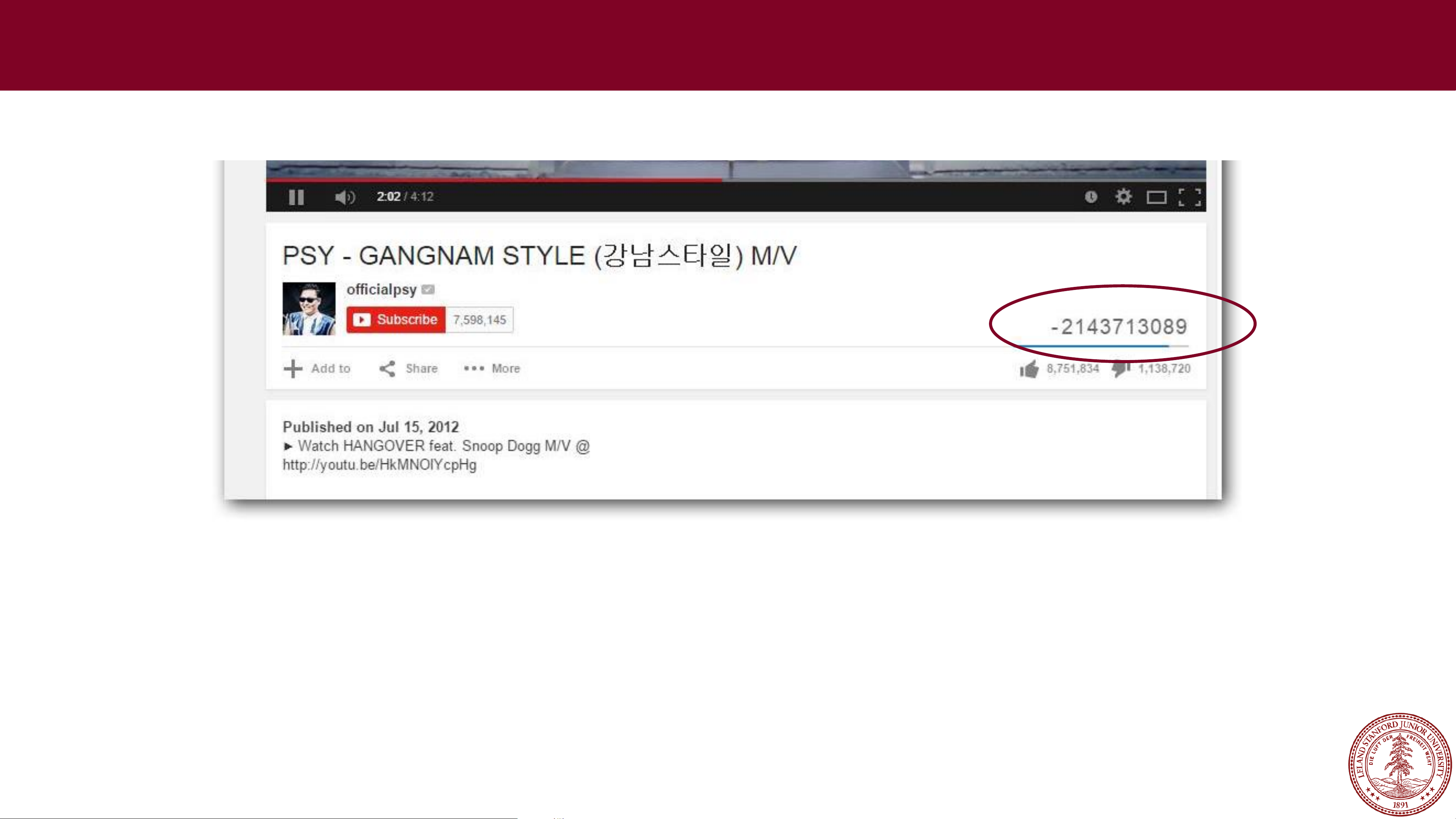

YouTube fell into this trap —their view counter was a signed, 32-bit int. They

fixed it after it was noticed, but for a while, the view count for Gangnam Style

(the first video with over INT_MAX number of views) was negative.

Overflow in Signed Addition

Signed overflow wraps around to the negative numbers.

$ ./signed_overflow

a = 2147483647

b = 1

a + b = -2147483648

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<limits.h> // for INT_MAX

int main() {

int a = INT_MAX;

int b = 1;

int c = a + b;

printf("a = %d\n",a);

printf("b = %d\n",b);

printf("a + b = %d\n",c);

return 0;

}

Technically, signed integers in C produce

undefined behavior when they overflow. On

two's complement machines (virtually all

machines these days), it does overflow

predictably. You can test to see if your addition

will be correct:

// for addition

#include <limits.h>

int a = <something>;

int x = <something>;

if ((x > 0) && (a > INT_MAX - x)) /* `a + x` would overflow */;

if ((x < 0) && (a < INT_MIN - x)) /* `a + x` would underflow */;

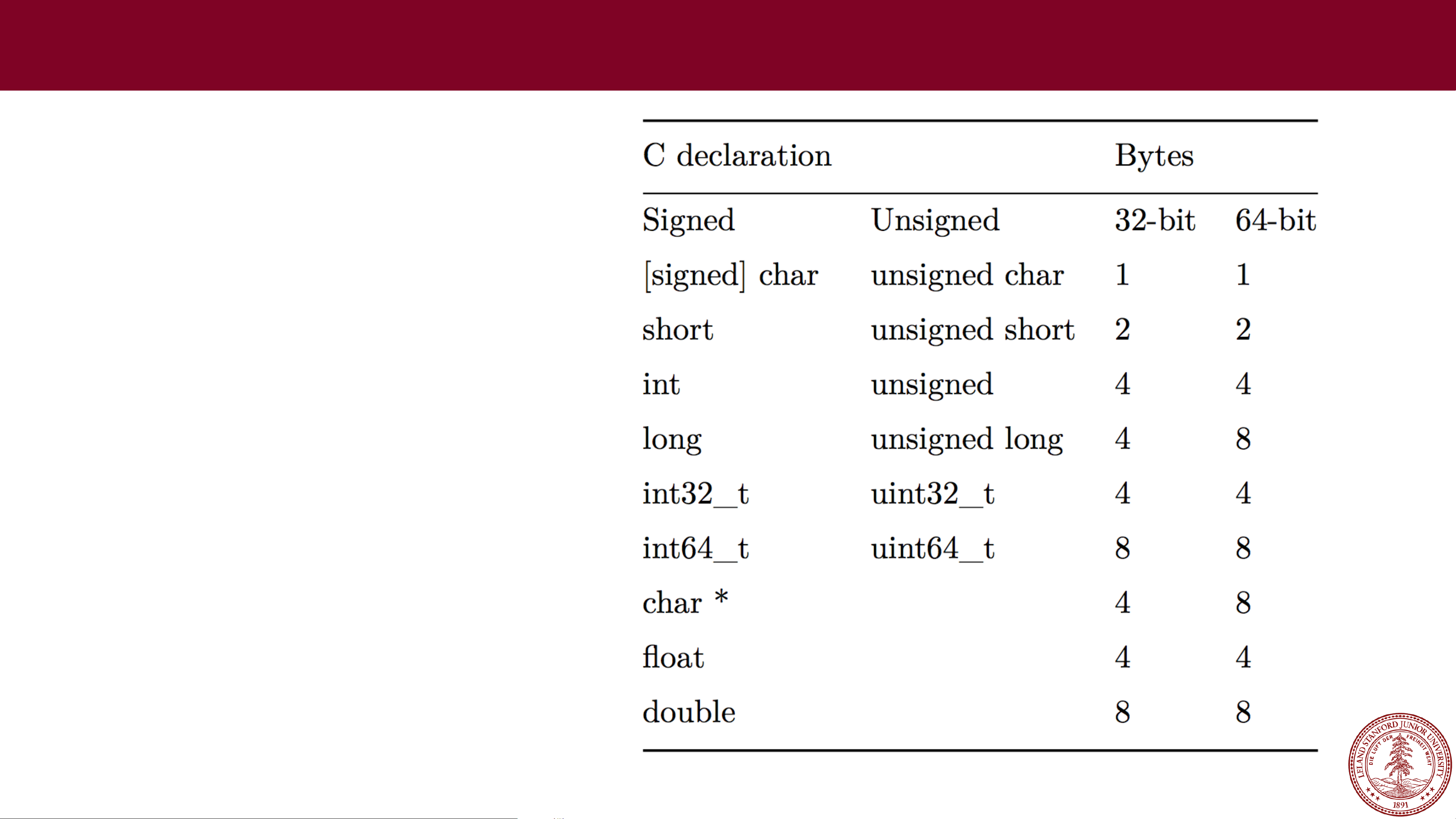

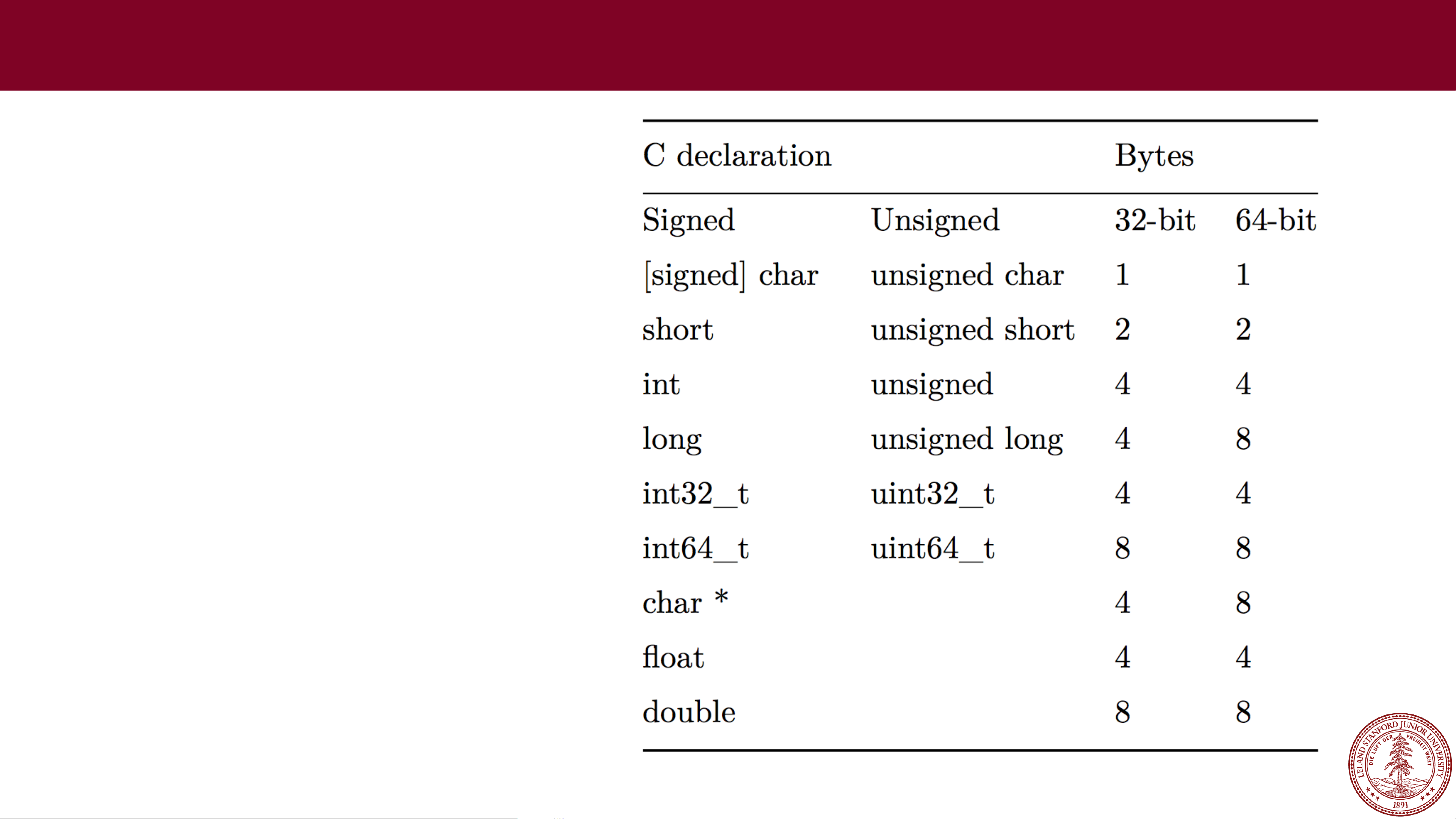

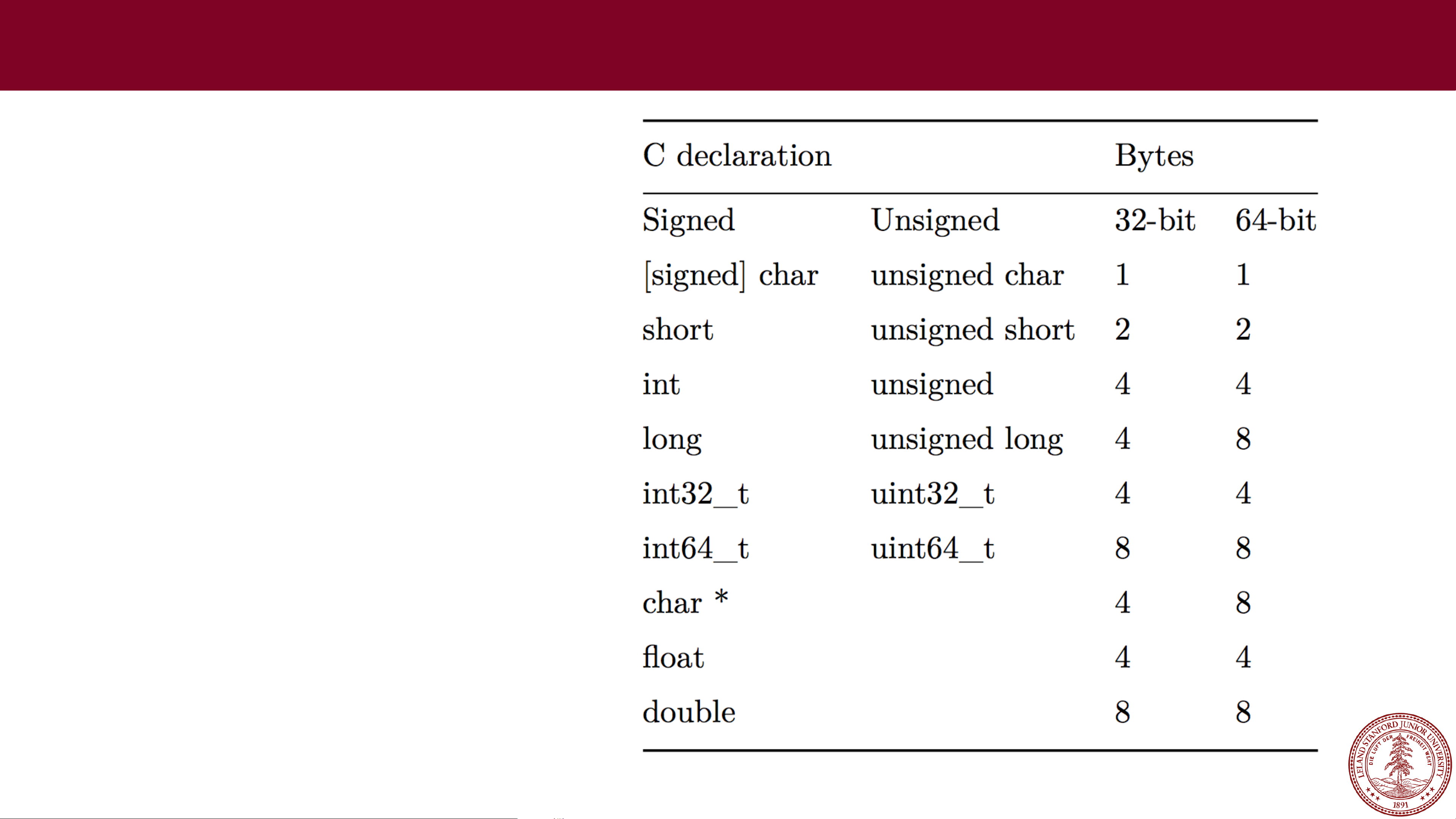

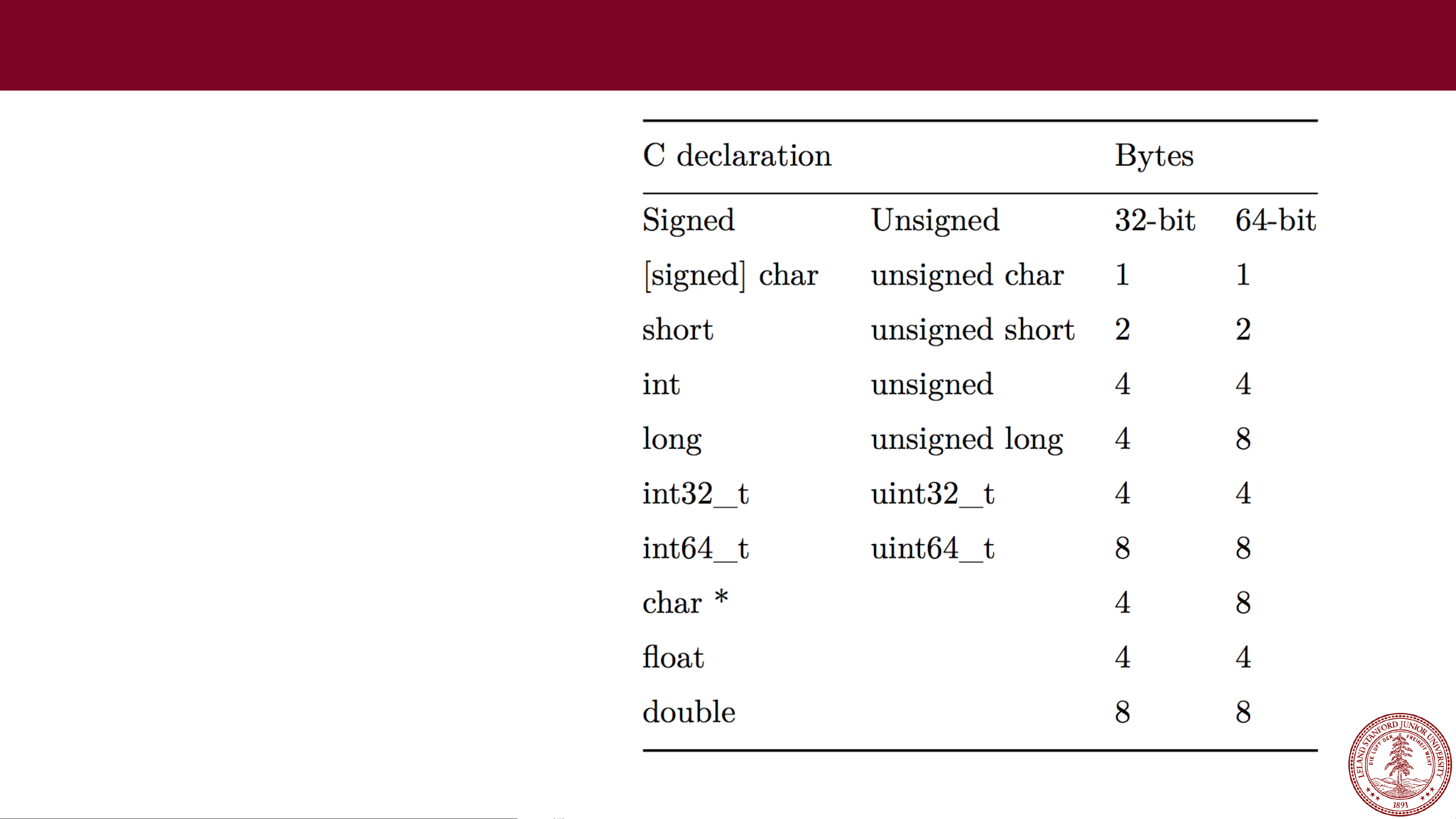

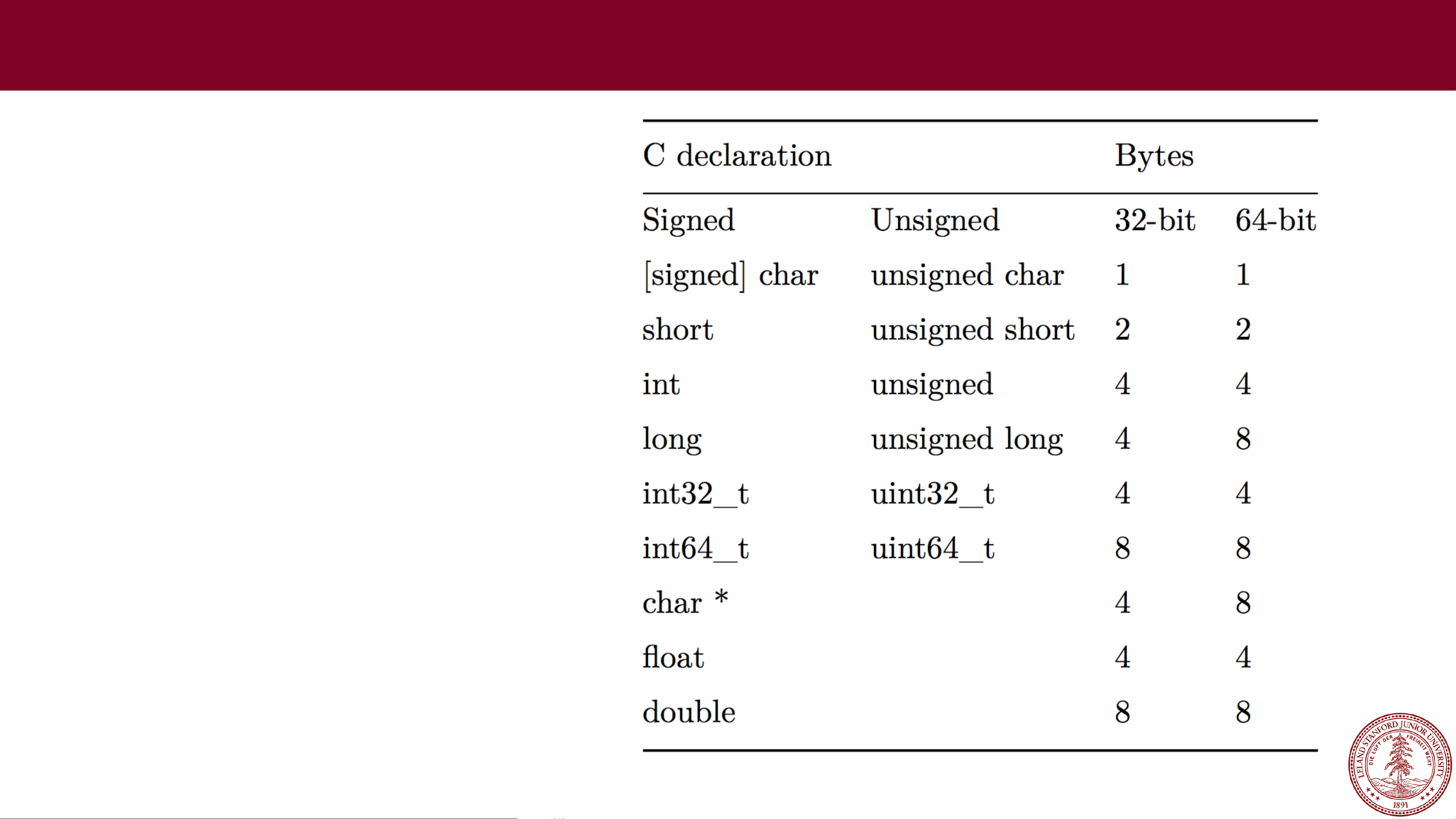

Data Sizes

Data Sizes

We found out above that on the

myth computers, the int

representation is comprised of

32-bits, or four 8-bit bytes. but

the C language does not

mandate this. To the right is

Figure 2.3 from your textbook:

Data Sizes

There are guarantees on the

lower-bounds for type sizes,

but you should expect that the

myth machines will have the

numbers in the 64-bit column.

Data Sizes

You can be guaranteed the

sizes for int32_t (4 bytes)

and int64_t (8 bytes)

Data Sizes

We briefly mentioned unsigned

types on the first day of class.

These are integer types that

are strictly positive.

By default, integer types are

signed.

Data Sizes

C allows a variety of ways to

order keywords to define a

type. The following all have the

same meaning:

unsigned long

unsigned long int

long unsigned

long unsigned int

Addressing and Byte Ordering

On the myth machines, pointers are 64-bits long, meaning that a program can

"address" up to 264 bytes of memory, because each byte is individually addressable.

This is a lot of memory! It is 16 exabytes, or 1.84 x 1019 bytes. Older, 32-bit

machines could only address 232 bytes, or 4 Gigabytes.

64-bit machines can address 4 billion times more memory than 32-bit machines...

Machines will not need to address more than 264 bytes of memory for a long, long

time.

Addressing and Byte Ordering

We've already talked about the fact that a memory address (pointer) points to a

particular byte. But, what if we want to store a data type that has more than one

byte?

The int type on our machines is 4 bytes long. So, how is a byte stored in memory?

We have choices!

First, let's talk about the ordering of the bytes in a 4-byte hex number. We can

represent an ints as 8-digit hex numbers:

0x01234567

We can separate out the bytes:

0x 01 23 45 67

Addressing and Byte Ordering

01 23 45 67

0000 0001 0010 0011 0100 0101 0110 0111

--------- --------- --------- ---------

most significant least significant

Some machines choose to store the bytes ordered from least significant byte to most significant byte, called “little endian” (because the “little end” comes first).

Other machines choose to store the bytes ordered from most significant byte to least significant byte, called “big endian” (b

Addressing and Byte Ordering

•Our 0x01234567 number would look like this in memory for a little endian computer (which, by the way, is the way the myth computers store in

•A big-endian representation would look like this:

Many times we don’t care how our integers are stored, but in cs107 we will! Let’s look at a sample program and dig under the hood to see how little

byte: 67 45 23 01

address: 0x100 0x101 0x102 0x103

byte: 01 23 45 67

address: 0x100 0x101 0x102 0x103

Addressing and Byte Ordering

•Our 0x01234567 number would look like this in memory for a little endian computer (which, by the way, is the way the myth computers store in

address: 0x100 0x101 0x102 0x103

value: 67 45 23 01

•A big-endian representation would look like this:

address: 0x100 0x101 0x102 0x103

value: 01 23 45 67

Many times we don’t care how our integers are stored, but in cs107

we will! Let’s look at a sample program and dig under the hood to see

how little-endian works.

Addressing and Byte Ordering

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main() {

// a variable

int a = 0x01234567;

// print the variable in big endian format

printf("a's value: 0x%.8x\n",a);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Addressing and Byte Ordering

$ gcc -g -O0 -std=gnu99 big_endian.c -o big_endian

$ ./big_endian

a's value: 0x01234567

$ gdb big_endian

GNU gdb (Ubuntu 7.7.1-0ubuntu5~14.04.3) 7.7.1

...

(gdb) break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x400535: file big_endian.c, line 6.

(gdb) run

Starting program: /afs/.ir.stanford.edu/users/c/g/cgregg/107/lectures/lecture2_bits_bytes_continued/big_endian

Breakpoint 1, main () at big_endian.c:6

6 int a = 0x01234567;

(gdb) n

9printf("a's value: 0x%08x\n",a);

(gdb) p/x a

$1 = 0x1234567

(gdb) p &a

$2 = (int *) 0x7fffffffe98c

(gdb) x/16bx &a

0x7fffffffe98c: 0x67 0x45 0x23 0x01 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

0x7fffffffe994: 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x45 0x2f 0xa3 0xf7

(gdb)

Note the ordering: 0x01234567 is stored as Little Endian!

3 Minute Break!

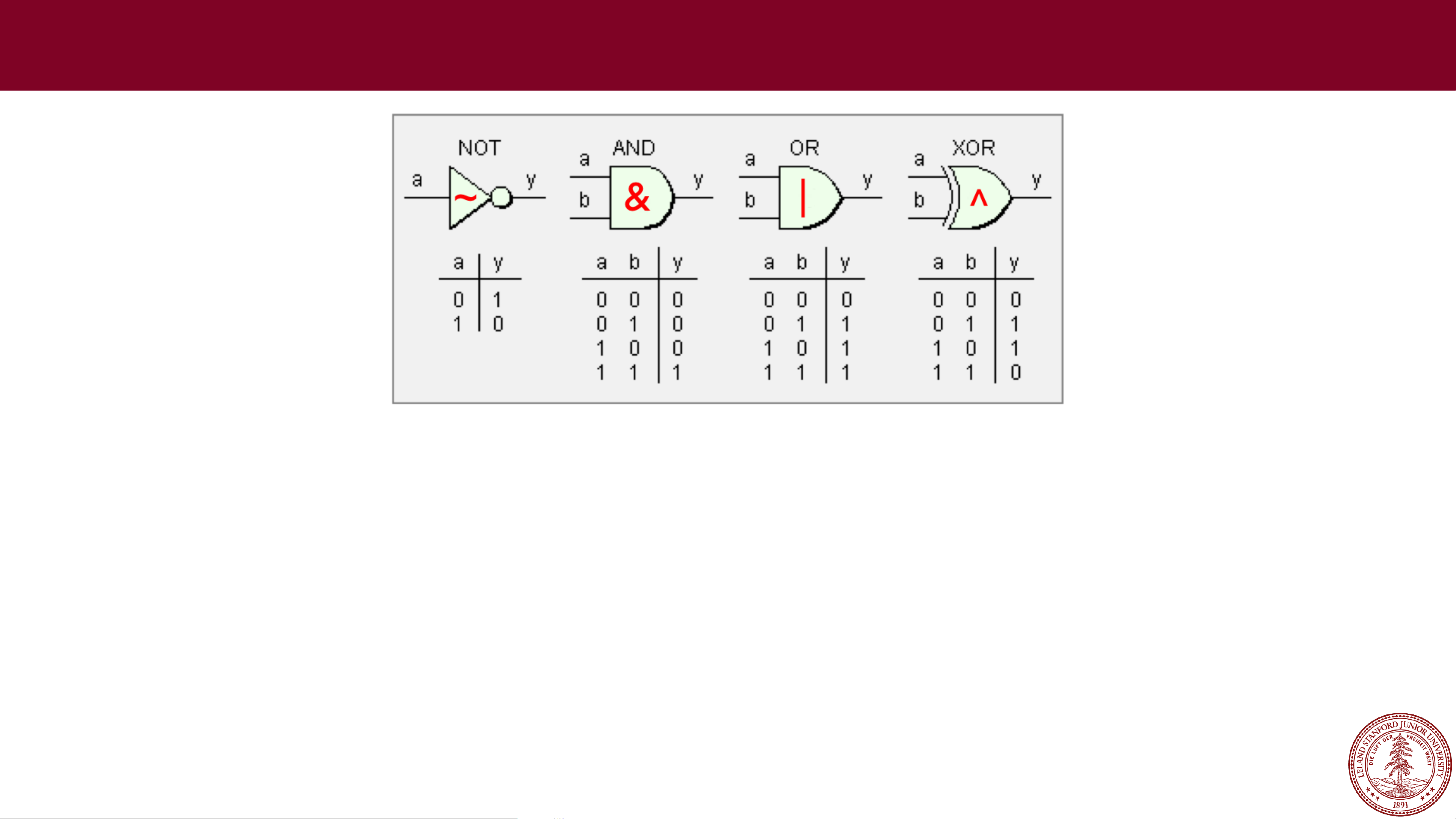

Boolean Algebra

Boolean Algebra

•Because computers store values in binary, we need to learn about boolean

algebra. Most of you have already studied this in some form in math classes

before, but we are going to quantify it and discuss it in the context of

computing and programming.

•We can define Boolean algebra over a 2-element set, 0 and 1, where 0

represents false and 1 represents true.

•The symbols are: ~for NOT, &for AND, |for OR, and ^for "exclusive or,"

which means that if one and only one of the values is true, the expression is

true.

Boolean Algebra

•Be careful! There are logical analogs to some of these that you have used in

C++ and other programming languages: !(logical NOT), && (logical AND),

and || (logical OR), but we are now talking about bit operations that result

in 0 or 1 for each bit in a number.

•The bitwise operators use single character representations for AND and OR,

not double-characters.

Boolean Algebra

•When a boolean operator is applied to two numbers (or, in the case of ~, a

single number), the operator is applied to the corresponding bits in each

number. For example:

0110

& 1100

----

0100

0110

| 1100

----

1110

0110

^ 1100

----

1010

~ 1100

----

0011

Boolean Algebra: Mystery Function

•Let's look at a mystery function!

$ ./mystery 4 5

// mystery1.c

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<stdio.h>

void mystery(int *x, int *y) {

if (x != y) {

*y = *x ^ *y;

*x = *x ^ *y;

*y = *x ^ *y;

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int x = atoi(argv[1]);

int y = atoi(argv[2]);

printf("x:%d, y:%d\n",x,y);

mystery(&x,&y);

printf("x:%d, y:%d\n",x,y);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Boolean Algebra: Mystery Function

•Let's look at a mystery function!

// mystery1.c

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<stdio.h>

void mystery(int *x, int *y) {

if (x != y) {

*y = *x ^ *y;

*x = *x ^ *y;

*y = *x ^ *y;

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int x = atoi(argv[1]);

int y = atoi(argv[2]);

printf("x:%d, y:%d\n",x,y);

mystery(&x,&y);

printf("x:%d, y:%d\n",x,y);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

$ ./mystery 4 5

x:4, y:5

x:5, y:4

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XOR_swa

p_algorithm

This relies on the fact that x^x == 0,

and the associativity and commutativity

of the exclusive or function.

Incidentally, if you XOR a number with

all 1s, you get the complement!

Boolean Algebra: Operations on bit flags

We can represent finite sets with bit vectors, where we can perform set functions

such as union, intersection, and complement. For example:

bit vector a = [01101001] encodes the set A = {0,3,5,6} (reading the 1 positions

from right to left, with #0 being the right-most, #7 being the left-most)

bit vector b = [01010101] encodes the set B = {0,2,4,6}

The |operator produces a set union:

a | b → [01111101], or A ∪B = {0,2,3,4,5,6}

The &operator produces a set intersection:

a & b → [01000001], or A ∩ B = {0,6}

Boolean Algebra: Bit Masking

A common use of bit-level operations is to implement masking operations, where

a mask is a bit pattern that will be used to choose a selected set of bits in a word.

For example, the mask of 0xFF means the lowest byte in an integer. To get the

low-order byte out of an integer, we simply use the bitwise AND operator with the

mask:

int j = 0x89ABCDEF;

int k = j & 0xFF; // k now holds the value 0xEF,

// which is the low-order byte of j

A useful expression is ~0, which makes an integer with all 1s, regardless of the

size of the integer.

Boolean Algebra: Bit Masking

Challenge 2: write an expression that complements all but the least significant

byte of j, with the least significant byte unchanged. E.g.

0x87654321 → 0x789ABC21

Challenge 1: write an expression that sets the least significant byte to all ones,

and all other bytes of the number (assume it is the variable j) left unchanged E.g.

0x87654321 → 0x876543FF

Possible answer: j ^ ~0xFF

Possible answer: j | 0xFF

Boolean Algebra: Shift Operations

C provides operations to shift bit patterns to the left and to the right.

The << operator moves the bits to the left, replacing the lower order bits with

zeros and dropping any values that would be bigger than the type can hold:

x << k will shift xto the left by knumber of bits.

Examples for an 8-bit binary number:

00110111 << 2 returns 11011100

01100011 << 4 returns 00110000

10010101 << 4 returns 01010000

Boolean Algebra: Shift Operations

There are actually two flavors of right shift, which work differently depending on

the value and type of the number you are shifting.

A logical right shift moves the values to the right, replacing the upper bits with 0s.

An arithmetic right shift moves the values to the right, replacing the upper bits with

a copy of the most significant bit. This may seem weird! But, we will see why this

is useful soon!

Examples for an 8-bit binary number:

Logical right shift:

00110111 >> 2 returns 00001101

10110111 >> 2 returns 00101101

01100011 >> 4 returns 00000110

10010101 >> 4 returns 00001001

Examples for an 8-bit binary number:

Artithmetic right shift:

00110111 >> 2 returns 00001101

10110111 >> 2 returns 11101101

01100011 >> 4 returns 00000110

10010101 >> 4 returns 11111001

Shift Operation Pitfalls

There are two important things you need to consider when using the shift

operators:

1. The C standard does not precisely define whether a right shift for signed

integers is logical or arithmetic. Almost all compilers / machines use arithmetic

shifts for signed integers, and you can most likely assume this. Don't be

surprised if some Internet pedant yells at you about it some day. :) All unsigned

integers will always use a logical right shift (more on this later!)

2. Operator precedence can be tricky! Example:

1<<2 + 3<<4 means this: 1 << (2 + 3) << 4, because addition and

subtraction have a higher precedence than shifts!

Always parenthesize to be sure:

(1<<2) + (3<<4)

Practice!

Let's take a look at lots of examples:

If you want to try the examples out yourself. On myth:

$ cd CS107

$ cp -r /afs/ir/class/cs107/lecture-code/lect3 .

cd lect3

make

ls # to see the files

References and Advanced Reading

•References:

•argc and argv: http://crasseux.com/books/ctutorial/argc-and-argv.html

•The C Language: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C_(programming_language)

•Kernighan and Ritchie (K&R) C: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=de2Hsvxaf8M

•C Standard Library: http://www.cplusplus.com/reference/clibrary/

•https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bitwise_operations_in_C

•http://en.cppreference.com/w/c/language/operator_precedence

•Advanced Reading:

•After All These Years, the World is Still Powered by C Programming

•Is C Still Relevant in the 21st Century?

•Why Every Programmer Should Learn C