x86 Assembly

x86 Assembly

Machine

Machine

| Type | Form | Operand value | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | $Imm | Imm | Immediate |

| Register | ra | R[ra] | Register |

| Memory | Imm | M[Imm] | Absolute |

| Memory | (ra) | M[R[ra] | Indirect |

| Memory | Imm(rb) | M[Imm + R[rb]] | Base + displacement |

| Memory | (rb,ri) | M[R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | ( ,ri ,s) | M[R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm( ,ri ,s) | M[Imm + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | (rb, r; ,s) | M[R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri,s) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Type | Form | Operand value | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | $Imm | Imm | Immediate |

| Register | ra | R[ra] | Register |

| Memory | Imm | M[Imm] | Absolute |

| Memory | (ra) | M[R[ra] | Indirect |

| Memory | Imm(rb) | M[Imm + R[rb]] | Base + displacement |

| Memory | (rb,ri) | M[R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | ( ,ri ,s) | M[R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm( ,ri ,s) | M[Imm + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | (rb, r; ,s) | M[R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri,s) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Type | Form | Operand value | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | $Imm | Imm | Immediate |

| Register | ra | R[ra] | Register |

| Memory | Imm | M[Imm] | Absolute |

| Memory | (ra) | M[R[ra] | Indirect |

| Memory | Imm(rb) | M[Imm + R[rb]] | Base + displacement |

| Memory | (rb,ri) | M[R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | ( ,ri ,s) | M[R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm( ,ri ,s) | M[Imm + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | (rb, r; ,s) | M[R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri,s) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Type | Form | Operand value | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | $Imm | Imm | Immediate |

| Register | ra | R[ra] | Register |

| Memory | Imm | M[Imm] | Absolute |

| Memory | (ra) | M[R[ra] | Indirect |

| Memory | Imm(rb) | M[Imm + R[rb]] | Base + displacement |

| Memory | (rb,ri) | M[R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri]] | Indexed |

| Memory | ( ,ri ,s) | M[R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm( ,ri ,s) | M[Imm + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | (rb, r; ,s) | M[R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

| Memory | Imm(rb,ri,s) | M[Imm + R[rb] + R[ri] · s] | Scaled indexed |

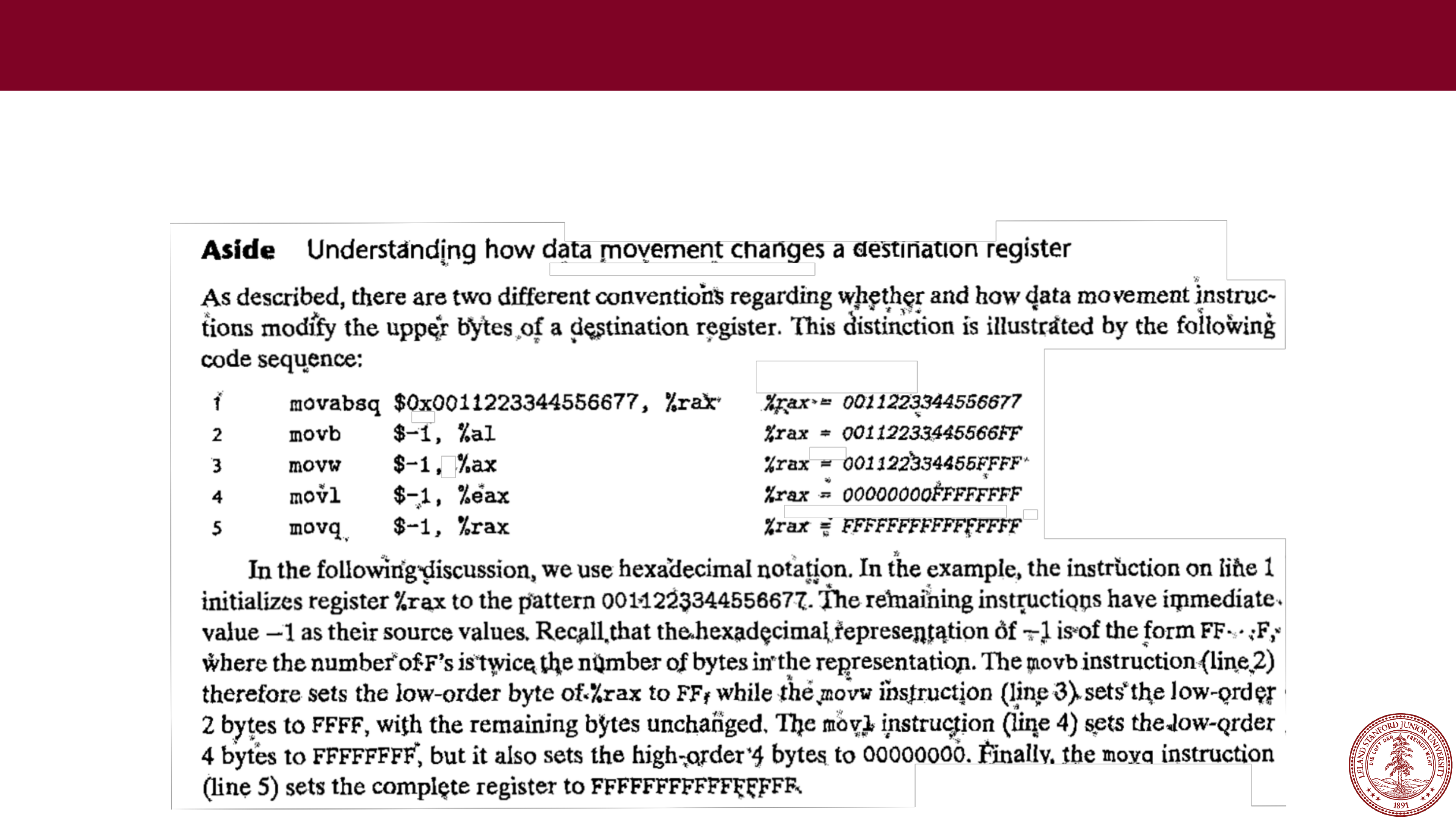

![The most generic operand form: Imm(rb, ri, rs) = M[Imm + R[rb]+R[ri]*s], Scaled Indexed](10-AssemblyPart1-img/img0007.png) Operand Forms

Operand Forms

3 minute break

3 minute break

More C to Assembly

More C to Assembly

Extra Slides

Extra Slides