Today: Bit, code, functions, expressions, start while-loop

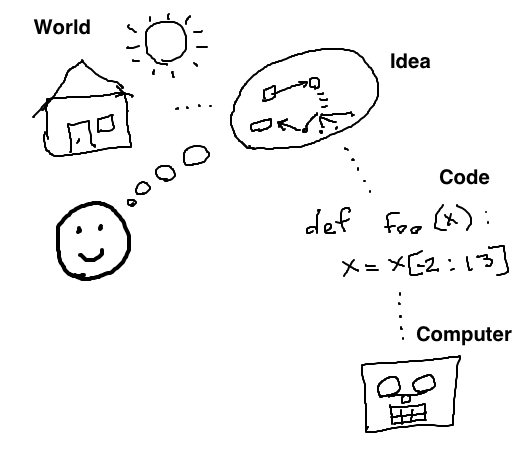

This is the zoomed out background of the whole course.

Computers are invaluable, solving real problems in the world. But what is the structure between the real world and the computer?

You have an insight about something useful to do in the world, an idea. You structure and translate the idea into code. Dumbing it down, essentially, to the language where the computer can handle it. The computer is very powerful in its way, but can only deal with simple, mechanical inputs, which is why programmers exist. As you endure countless obscure failures and error messages from the computer, keep in mind that the computer just does what it is told. The actual idea comes from you.

A computer program (or "app") is a mass of code for the computer to run. The code in a program is divided into smaller, logical units of code called functions, much as all the words that make up an essay are divided into logical paragraphs.

Python programs are written as text in files with names like "example.py". The program text will be divided into many functions. As we start writing programs, most of our time will be spent writing lines of code inside of one or another function as we build up the whole program. In a Python program, each function begins with the word def

We have this "Bit" robot which lives in a rectangular world divided into squares, like a chessboard. Bit is my research project - working on opening up to the world soon. We'll use Bit at the start of CS106A to introduce and play with key parts of Python. The code driving Bit around is 100% Python code. The nice thing about Bit code is that the each action has an immediate, visual results, so you can see what each line of code does.

Bit faces in the four cardinal directions, and can move forward one square at a time. Bit can paint the square it is on red, green, or blue. Black squares and the sides of the world are not clear for a move - bit cannot move there.

Here is the Bit robot, shown as a little "V":

Here is a the same view of Bit, showing the "Classic" robot appearance, for which some people develop a hard to explain emotional attachment. You can use either appearance, and everything else works the same.

For reference, here is a more detailed guide to Bit's features: Bit Reference. In particular, the reference lists the functions that Bit understands; in CS this is known as "documentation" of the available functions, or just the "docs".

Below is the code in a Python function named "do_bit1" that creates bit in a little world and commands bit to do a few things. There is syntax here - not pretty. We'll focus on what bit does for each line.

def do_bit1(filename):

bit = Bit(filename) # Creates "before" picture

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right()

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

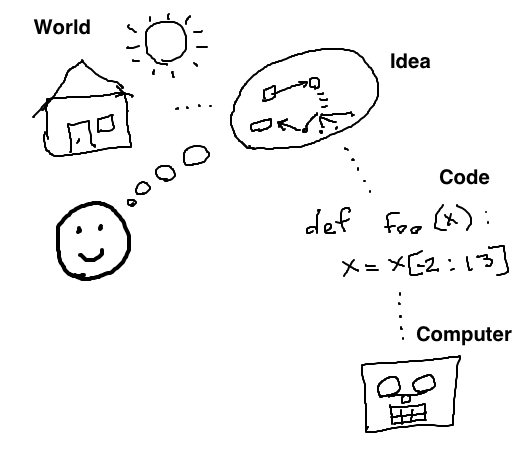

1. The function starts bit off facing the right side of the world with a couple empty squares in front (before-run picture):

2. The code in the function moves bit over a couple squares, painting some of them. So running the function does those actions, and afterwards the world looks like this (after-run picture):

Here is the bit1 problem on the experimental server (you can run it too, or just watch):

> do_bit1() function

We'll use Nick's experimental server for code practice. See the "Bit1" section at the very top; the "bit1" problem is there. Often the code in a lecture example like this will be incomplete, and we'll work it out in lecture. There is a Show Solution button on each problem, so you can always play with it again later and check your answer.

Click the Run button and see what the function does. See how bit takes actions in the world first, and then we'll fill in what's going on with the lines of code. You can use the "steps" slider to run the code forwards and backwards, seeing the details of the run.

Now let's look at all of that syntax, discussing what each line of code does.

def do_bit1(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right()

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

The Run button in the web page runs this do_bit1 function, running its lines of code from top to bottom. Running a function is also known as "calling" that function. In this case, each line in the function commands bit to do this or that, so we see bit move around as the function runs from top to bottom.

bit = Bit(filename) - Set Up World

def do_bit1(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

...

This line creates the world with bit in it, and sets the variable bit to point to the robot. We needs this line once at the top to set things up, then the later lines use the robot. We'll explain this with less hand-waving later. This drawing shows the setup - the bit robot is created along with its world, and the variable bit is set to point to the robot.

bit.move() = Call the "move" FunctionBuilding a computer program, you inevitably call functions you did not write to solve parts of the problem. The functions have, in CS parlance, "documentation" describing what each function is named and what it does — for Bit we have the Bit Reference documentation.

bit.paint('blue') = Call the "paint" functionbit.left() and bit.right()def = Define a FunctionNow we'll go back and talk about the first line. This defines a function named do_bit1 that holds the lines of code we are running.

def do_bit1(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

...

"Syntax" is not a word that regular people use very often, but it is central in computer code. The syntax of code takes some getting used to, but is not actually difficult.

> bit2 exercise

Bit begins at the upper left square facing the right side of the world. Paint the square below the start square green, and the square below that green as well, ending like this:

Try that one on your own to practice the basic Bit functions, but we're not doing it in lecture. There's a few problems in that for more practice.

The word pass is a placeholder for your code, remove it. Conceptually this does not look hard, but expect to make some mistakes as you get the little syntax and naming details right as required by the (lame, needy) computer

For similar examples with solutions, see the bit1 section on the experimental server

We will hand out homework 1 in the second lecture. However, here are the first two problems from the homework which you can work on now if you like. Do not be surprised if you make errors on these at first, as you need to get used to the code structure. These just use the basic move/turn/paint actions (no loops), so not as glamorous as the stuff we'll do soon, but you have to start somewhere! It's also fine if you want to ignore these for now and get started Wed or Thu.

> bit-beta

Our next topic, mostly not for day 1.

Now we'll start looking at the "loop" structure which is very powerful

We'll see how far we get with this in lecture-1.

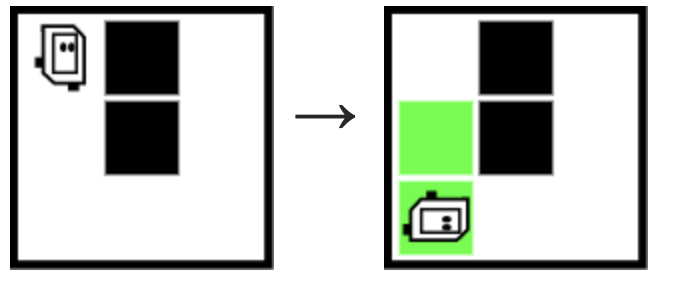

Bit starts at the upper left square as usual. Move Bit forward until blocked by a wall, painting every moved-to square green.

Follow the link to the go-green problem. The code there is complete, so just click Run and watch it run a few times to get a feel for the loop, and then we'll look at the details.

> go-green

...

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

The while-loop repeats the needed lines for the go-green problem. Loops are powerful, letting us easily run lines many times. The key part is how the while-loop stops at the right spot. To understand that, we will introduce Python "expressions".

An "expression" is a piece of code that, when it runs, returns a value to that spot in the code.

Here's is a line of Python code that assigns a value to a variable, and the right side of it is a mathematical expression:

When that line of code runs, Python "evaluates" the expression, reducing it to a value. We also say that the expression "returns" that value. A nice way to visualize the evaluation is an arrow going through the expression, showing the value coming out, like this:

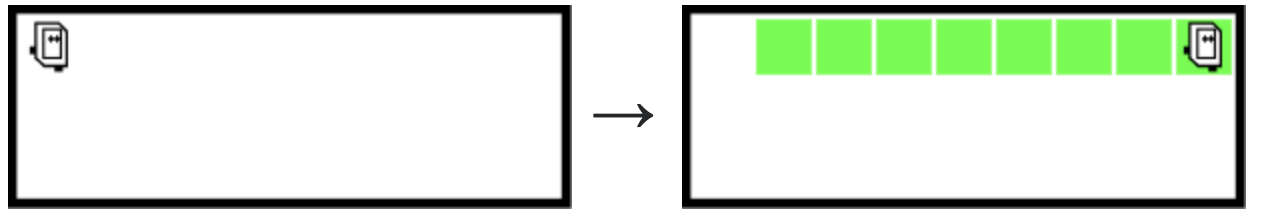

bit.front_clear() ExpressionIn Bit's world, the way forward is clear if the square in front of Bit is not blocked by the black edge of the world or a solid black square.

Bit has a function front_clear() which acts as an expression, with a True or False value coming out of it. The function front_clear() checks the square in front of Bit, returning True if the square is clear for a move, and False otherwise.

Here are visualizations of how the bit.front_clear() expression works when it runs, with the True or False return value coming out of the expression:

We will look the details of the while-loop operation next time. Essentially, for the go-green problem, the loop uses bit.front_clear() as a test. The loop runs so long as bit.front_clear() returns True, and stops when it returns False. We will pursue the details in the next lecture.

...

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')