Today: while loop, if statement, ==, left_clear(), bit puzzles, make-a-drawing strategy

We'll work a bunch of little problems today, you may want to review them later. Or you could start the homework, and then if you get stuck, go back and review the related problems on lecture.

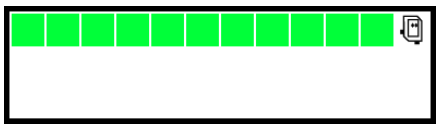

Recall from lecture-1 .. the go-green problem.

Follow the link to the go-green problem. The code there is complete, so run it and watch it run a few times to get a feeling for what the loop looks like. We'll look at the details below.

> go-green

The loop is a big increase in power, running lines many times. There are a few different types of loop. Here we will look at the while loop.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

The while loop depends on a Python "expression". An expression is a piece of code that, when it runs, returns a value to that spot in the code.

Here's is a line of Python code that assigns a value to a variable, and the right side of it is a mathematical expression:

When that line of code runs, Python "evaluates" the expression, reducing it to a value. We also say that the expression "returns" that value. A nice way to visualize the evaluation is an arrow going through the expression, showing the value coming out, like this:

bit.front_clear() ExpressionIn Bit's world, the way forward is clear if the square in front of Bit is not blocked by the black edge of the world or a solid black square.

Bit has a function front_clear() which acts as an expression, with a True or False value coming out of it. The function front_clear() checks the square in front of Bit, returning True if the square is clear for a move, and False otherwise.

Here are visualizations of how the bit.front_clear() expression works when it runs, with the True or False return value coming out of the expression:

while test-expression:

body lines

The while loop has a test and a body. and the sequence it follows is pretty reasonable.

The diagram is busy looking, but basically it works like this: the loop runs the lines of code in the body again and again, until the test is False. Here's the detailed sequence of actions:

1. The loop evaluates the test-expression at the top. Does it return True or False? In this case, the test is bit.front_clear() (next section). (True and False are the "boolean" values, see the guide chapter: booleans).

2. If the test evaluates to True, the loop runs all the lines in the body, from top to bottom. After running the body, the loop goes back to step (1), checking the test again.

3. Eventually the test evaluates to False, the loop is done, and the run continues after the loop.

> go-green

Run the go-green function, and watch it to see how the while loop runs the body lines many times, until bit reaches the wall. In particular, use the "step" button to advance one line at a time as bit is on the next-to-last square and then the last square, seeing the test return True for all squares but the last.

Position bit a few squares from the end with the steps slider. Step to line 5 and stop. What line comes after line 5?

Step to line 3. What line comes next? It depends on where bit is actually. Run to the end to see both cases.

When the while test is True, bit keeps moving forward, and when False bit stops. We think of this as "True = Go". Later when we're writing code to advance bit through some other situation, we'll use "True = Go" as a mnemonic to think about what test we need.

It follows that the square where bit stops, the test is False. The preceeding squares where bit kept moving, the test was True.

Using bit.front_clear() as the test and bit.move() in the body moves bit forward until its blocked. That's a common situation, in which case it's easy to simply use the loop from from go-green as an idiomatic phrase of code, also known as a "pattern". We don't have to re-think the loop from first principles each time.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint()

while bit.front_clear():

bit.paint()

bit.move()

Next example - use this to play with more features of loops. This code is complete.

> All-Blue

Often we have an English language description of what we want, and then we're thinking about the code to get that effect.

Description: Bit starts in the upper left square facing the right side of the world. Move bit forward until blocked. Paint every square bit occupies blue, including the first. When finished, turn bit to face downwards.

Differences from go-green: (1) first square is painted, (2) turn down on last square

def all_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

bit.paint('blue') # Paint before the loop

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.right() # Turn after the loop

Look at Case-3 and then Case-4. Turn off the Auto-Play option, so when you click Run, the world stays at the start, waiting for you to click Step. See how the while test behaves on Case-3 and then Case-4. For Case-4, the while-test is False the very first time! The result is, the loop body lines run zero times. This is fine actually. There were zero squares to move to, so looping zero times is perfect. This is an example of an "edge" case, the smallest possible input. It's nice that the while loop handles this edge case without any extra code.

The system tries to terminate the infinite loop code. Sometimes that does not work, and you have this infinite loop code running in your browser. In that case, often it will be fixed to close any other experimental server tabs, then shift-reload the problem tab. If that does not work, you can restart your browser to fix it.

For a loop to work, each run of the body needs to get closer to being done (i.e. close to being able to the test being False). With these bugs, bit is not making progress and so it never ends.

Here is a buggy All Blue - instead of move() have bit do right() and the left() - a sort of "waggle dance" like bees do in the hive. Notice that bit waggles but never moves forward. Bit can do this for eternity, and never leave that first square! Everyone has days like that.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.right() # waggle dance!

bit.left()

bit.paint('blue')

Run the code - you will see a message about a timeout, suggesting that this code does not seem to reach an end.

move vs. move()Python syntax requires the parenthesis () to make a function call. Unfortunately, if you forget them, which is easy to do, Python does not call the function. So the code below looks right, but actually it's an infinite loop. Bit never moves. Try it yourself and see, then fix it.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move

bit.paint('blue')

For extra practice, here are some more problems along the lines of All-Blue:

> red2

> go-back

> Bit Loop Section - problems using 1 or more loops

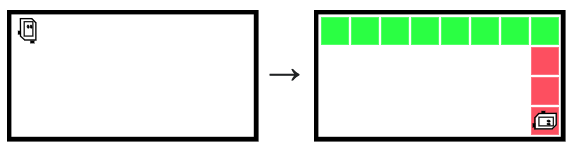

Suppose I have this problem:

What is the outline of the code to solve this?

Solution:

Use two loops one for each big move of the problem.

1. Use a while loop to move until blocked, moving across the top row, painting it green (as we've done before).

2. After the first loop, turn right. Then use a second until-blocked loop to move down, painting every square red.

We have two big actions here - the top row, and the right side. Solve each with its own loop, one loop after the other. This is our preferred approach.

Do Not try to solve it with a single loop that switches modes halfway along, or with two loops with one nested inside the other. Those can be made to work, but are prone to subtle bugs. We prefer to keep it simple. (The coyote2 example later on makes a similar point.)

def do_half_tree(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

# Loop across the top, painting every square green

bit.paint('green')

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

# Loop downwards, painting every moved-to square red

bit.right()

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('red')

The while-loop is power. If-statement is control, controlling if lines are run or not (for more details see the guide chapter: if/comparisons).

We'll run this simple bit of code first, so you can see what it does. Then we'll look at the bits of code that go into it.

For reference here is the code:

def change_blue(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

The if statement syntax has four parts — the word "if", boolean test-expression, colon, indented body lines

if test-expression:

body lines

Or structurally we can think of it like this:

Here are the key lines of change-blue. The "if" line has a lot of parts, so we'll look at them in turn.

....

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

....

bit.get_color()bit.get_color() VisualizationSuppose bit is on a squared painted 'blue', as on the first line below. When bit.get_color() is called in that situation, it returns the color of the current square, e.g. 'blue'. The special value None is returned if the square is blank (as on the last line).

1 + 2 -> 3 7 + 4 -> 11

== Compares Two Values - Boolean6 == 6 -> True 6 == 7 -> False 'red' == 'red' -> True # == used in if/while tests if x == 6: # run in here if x is 6 ...

Putting this all together, we can read the change-blue code word by word to see what it does.

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

if bit.get_color() == 'blue':

bit.paint('green')

Q: Usually we start with English and translate into Python. Here we do the reverse — what is the translation of the code in the loop into English?

A: For each moved-to square. If the square is blue, paint it green.

!= Not Equal Form== !=Translate each if-test into English

if bit.get_color() == 'red':

# if the square is 'red'

if bit.get_color() == None:

# if the square is blank, not painted

if bit.get_color() != 'red':

# if the square is anything other than 'red'

# e.g. 'green' or 'blue' or None

> change2

What if we want to change 2 colors?

'red' -> 'green' None -> 'blue'

This demonstrates a loop with 2 if-statements in it.

bit.right_clear()Here bit is facing the right side of the world. So bit's right side is towards the bottom of the world. In this case, bit.right_clear() returns True.

Here the square to bit's right is blocked, so bit.right_clear() returns False.

not

if bit.right_clear():

# if right is clear

if not bit.right_clear():

# if right is not clear,

# aka blocked

On the experimental server, the Bit Puzzles section has many problems where bit is in some situation and needs to move around using Python code. We'll look at the Coyote problems, and there are many more problems for practice.

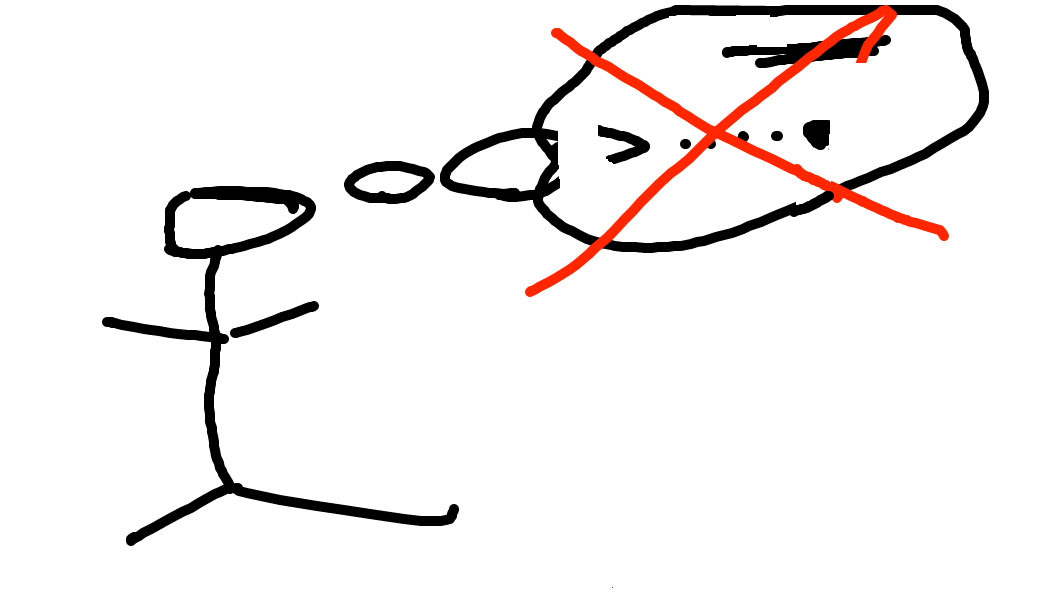

These problems have a lot of detail in them. Don't try to work it in your head, or just keep hitting the run button in the hopes it will work.

Don't do it just in your head - too much detail. Need to be able to work gradually and carefully.

Draw the start state and what you want. Then use the drawing to see the details, work out the code. The drawings do not need to be fancy, but it's easier to trace through your plan and the details on a sketch than in your head.

If you looked at the desk of a professional programmer, you would likely find little sketches like this scattered about.

We will demonstrate this drawings-process for the problems below.

We'll say Bit is the coyote from the old RoadRunner cartoons. In the cartoons, the coyote is always running off the side of the cliff and hanging in space for a moment.

For this problem, we want Bit to run forward until a space appears beneath, painting every moved-to square green.

while ??? :

bit.move()

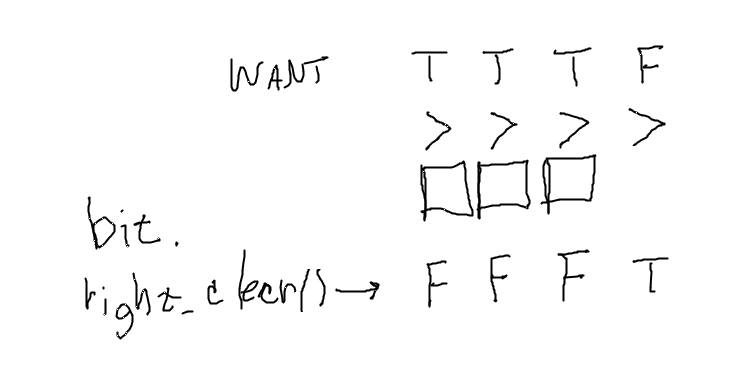

Question: What is the while-test to move off the cliff?

Put what the bit state we have and what we want on the drawing. Look at the drawing to think about the code to make the "want" part a reality.

Remember, True = Go, so we want a test that is True when there is a solid square below bit.

Guess: what about bit.right_clear() - put those T/F values on the drawing as something we have. They are the exact opposite of what we want - which is close! How to fix? Add not before the expression to invert T/F

Answer:

while not bit.right_clear():

bit.move()

The drawing pulls the details together, lets us figure out a tricky line of code.

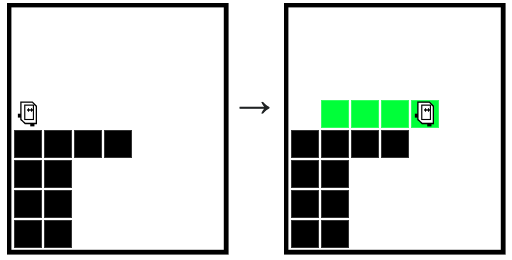

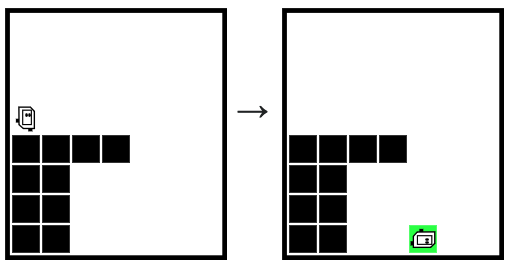

Look at Coyote2 - starts with a horizontal move like coyote, followed by a vertical move to the ground.

> coyote2

When bit goes along in a line and stops, we'll call that a "linear move".

This problem has 2 linear moves — one horizontal, then one vertical

When coding these up in CS106A, use one while loop for each linear move. So in this case, 2 while loops, one loop after the other. The stopping point of each linear move is encoded by the while-test up at the top of each loop.

Code can fail in so many ways, we have a preference for doing things in the most direct, straightforward way we can think ok. Or put another way, it's the old "keep it simple, stupid" KISS principle. In this case, we want you to use one while loop for each linear move, and put the logic about stopping in the while-test.

Coyote2 Solution code — one while loop for each linear move. The while-test for the horizontal loop-1 is not bit.right_clear(). The while-test for the vertical loop-2 is the plain bit.front_clear().

def coyote2(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

# Loop 1 - horizontal move until square has space below

while not bit.right_clear():

bit.move()

# Loop 2 - turn to face down, then move until blocked

bit.right()

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

bit.paint('green')

A common mistake for these problems goes like this: a while loop is written with an incorrect test, like say bit.front_clear() for loop-1, which will not stop on the right square. Observing that Bit does not stop in the right place, the student will add an if-statement to turn right within the loop, attempting to switch to the vertical move, e.g. if bit.right_clear(): .... However, this will go awry later, since the code is still inside the original while with the wrong test.

The correct approach focuses on getting the while-test working first, so bit stops exactly on the right square, and the code exits the first Get Bit to stop on the right square first, which may take a few tries, before adding more actions. Notice in the solution above how the lines after loop-1 are not indented within loop-1, they are after it. The loop-2 lines can proceed independently, as loop-1 has been left behind.

notThese are all in the "puzzle" section. Reminder: all lecture examples have a Show Solution button if you get stuck.

> climb

> encave (a little harder, like a homework prob)

> blue-dip

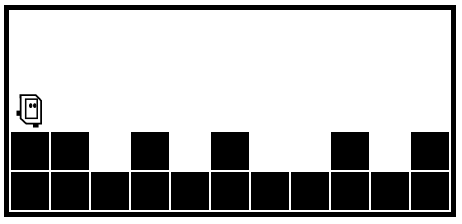

This is a more complicated problem. We'll work it out with drawings at every step to keep the details straight. In part we're showing the solution code, but more importantly we're showing the process for working through something this complicated.

Before:

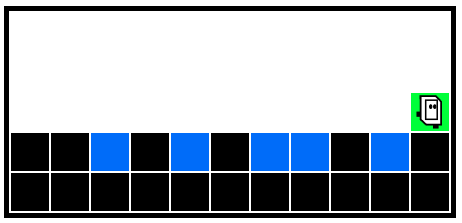

After:

We'll use a while loop to go all the way to the end. That's easy. Then put an if-statement inside to detect and handle each dip.

def blue_dip(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

# If dip - handle Dip here

Say we have the code to go the right side. The difficulty is detecting each dip - we want an if-statement with a test that is true when we are over the dip.

A: Test is bit.right_clear()

if bit.right_clear():

# handle dip in here

Need to go into the dip square and paint it blue. On the drawing, put what we have, work out the steps towards what we want.

Aside: Can't just tell the computer what you want the result to look like! You have this dumb robot and you need to spell out the needed steps.

Make a drawing to work out the steps.

Steps to move into dip: turn right, move, then paint blue. aka:

bit.right()

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

There's a bunch of detail here - bit's location, direction, blocks all around. We are using the drawing to keep those details clear, and work out the code steps with the drawing, vs. trying to do it in your head. This is the way to solve these problems. If you come to office hours with some broken bit situation, we will typically as you to make a drawing just as a first step - it's how we get these things working.

If you go to the desk of a professional programmer, you would not be surprised to see little sketches on scraps of paper, working out the details of some problem.

We need to go back up to the previous square so the while-loop can continue. Use the drawing to work out the code to go up one.

We are in the dip, facing down. Steps to get back up: turn left twice, then move (or could turn right twice and move, either way, we are doing a 180)

bit.left() bit.left() bit.move()

def blue_dip(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

# Clear square below

if bit.right_clear():

bit.right() # Down and paint

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

bit.left() # Move back up

bit.left()

bit.move()

Try running this form

> blue-dip

The above is pretty close but it has one problem which you may have spotted earlier, and in any case it does not work right when run. Look at how we move bit back up again:

Bug: The while loop assumes bit is facing the right side of the world and just moves bit forward. Our move-up code leaves bit on the correct square, but facing up which is the wrong way. Bit should be facing the right side of the world. Think of it this way - before we went down into the dip, bit was facing the right side of the world. Coming out of the dip, we need to set bit back the way it was, and then the while loop can continue as it did before. This is a slightly subtle bug, and nobody should feel bad for even an instant for writing it this way. The normal path is to have a few bugs, run the code, and then fix the bugs.

bit.right()We need a final bit.right() to face the right side of the world. There's also a final paint after the loop to paint the last square green (not indented).

def blue_dip(filename):

bit = Bit(filename)

while bit.front_clear():

bit.move()

# Clear square below

if bit.right_clear():

bit.right() # Down and paint

bit.move()

bit.paint('blue')

# Move back up, face right

bit.left()

bit.left()

bit.move()

bit.right()

# Paint last square green

bit.paint('green')

The point is not to write your code perfectly before it runs. The point is that you can't just keep clicking the Run button when things don't work. A drawing helps provide a path through the details, building and debugging the code step by step. Even very experienced programmers make little drawings like this to work out their ideas.