🌐 CS 106S: JavaScript Guide

Ben Yan, Winter 2025 (webpage structure inspired by Nick Parlante's handouts)

Hi there and welcome to JavaScript Land! The first class is mostly going over the syllabus and logistical stuff (and trying to figure out how we ended up all the way in McMurtry), but we're also being introduced to the beautiful, funky language which is JavaScript. We have an exercise with Caesar ciphers to get some practice and acrobatics with the language. Fun stuff ahead!

This JavaScript guide is a more fleshed-out or lectures-notes-style version of the JavaScript code tutorial at this link. It assumes some prior experience with general programming concepts (e.g., if and else, for loops, strings and arrays), at the level of a student entering CS 106B. But don't worry if otherwise (e.g., it's been a very hot minute since AP CSA); you can look through this reference guide at your own pace! Please feel free to ask me any questions, or for any clarifications during the workshop time, and I'll head over to chat :)

You're also welcome and encouraged to work through this in groups!

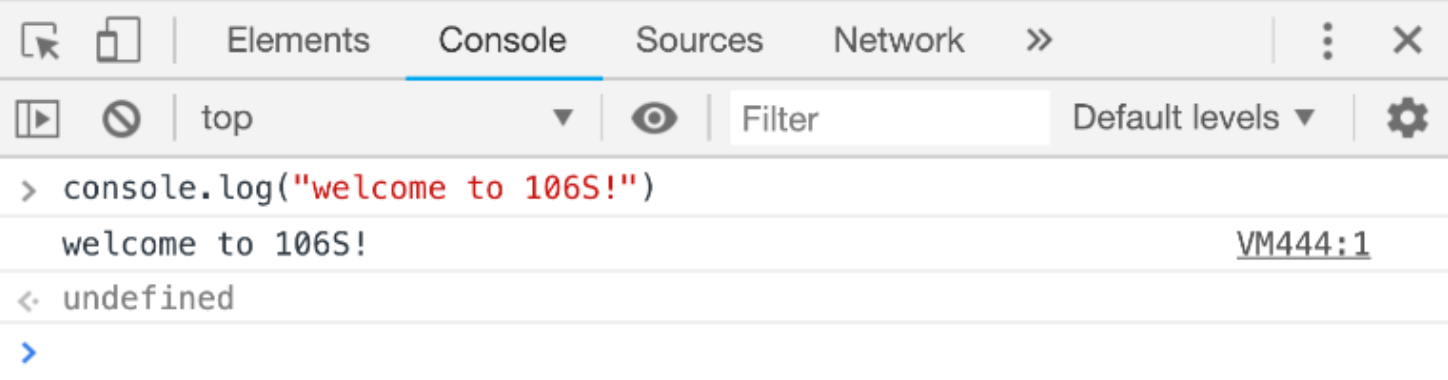

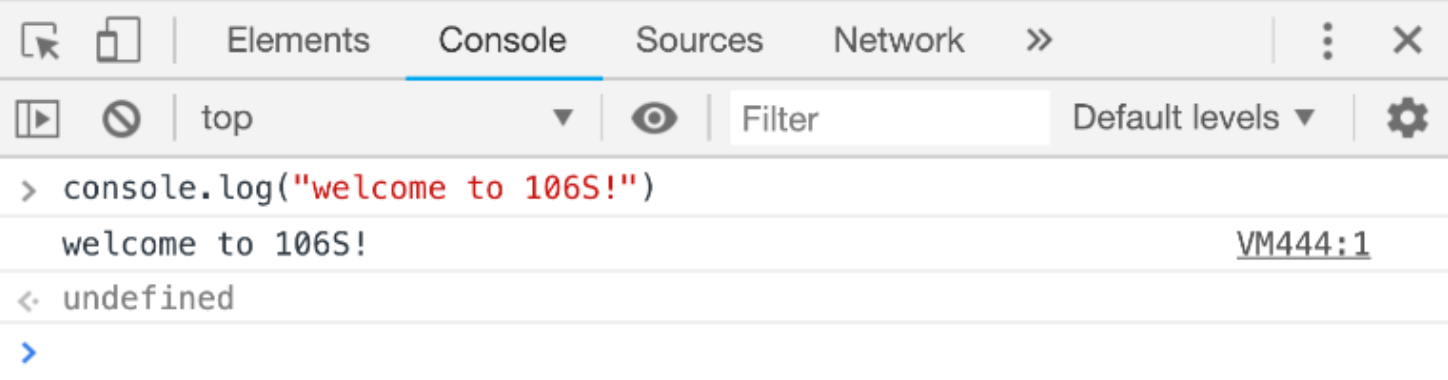

Running JavaScript in Browser

From the starter code folder you downloaded, open the index.html file in Google Chrome (on MacOS Finder, double-clicking the file typically works).

Then, press cmd-option- j (or ctrl-shift- j if on windows), not letting go of the previous key while pressing the next. A console should pop up, where you can type and run JavaScript code! Alternatively, if you're familiar with the Inspect Element tool, possibly due to mischief, you can head there; there should be an upper panel of tabs that reads Elements, Console, Sources, etc.. You'll want to click on Console.

I'd recommend split-screening so that you have the tutorial on one side, and index.html with the console open on the other side. That way, you can copy and tinker with any code here, and run it in the console to verify its output.

JavaScript Kick-off

Here's a simple Hello World program in JavaScript!

console.log("Hello World!");

JavaScript comments begin with a //, and while they're not executed as lines of actual code, they can help explain code and improve readability.

console.log("Hi there, my name is Ben!");

// introducing myself to the computer, in a

// friendly way in case they take over the world

Note that math (+,-,*,/ operators) works similarly to a language like Python. JavaScript represents all numbers as a unified Number type, so / between two integer values will perform regular, arithmetic division.

1 + 1; // => 2

10 - 4; // => 6

2 * 7; // => 14

3 / 2; // => 1.5

The % is the remainder operator i.e. the expression n % k evaluates to the remainder when n is divided by k.

4 % 2; // => 0

5 % 2; // => 1

6 % 2; // => 0

10 % 26; // => 10

Remainders can be useful for capturing alternating or "wrap-around" behavior in programs, e.g., time-keeping on clocks 🕰️. If it's 8:00 right now, then 7 hours later, it'll be 3:00, as times wrap around the 12-hour clock. This could have been computed with the following JavaScript expression:

(8 + 7) % 12 // 8+7 => 15 o'clock 🤔

// clock only has 12 hours (0-11), so 15%12 => 3:00

Lastly, in JavaScript, having a semicolon (;) at the end of each statement is optional! Up to you and your style preferences :)

Variables

We use the let keyword to define variables of any type (whether Number, String, Array, etc.). The syntax in JavaScript takes the form:

let variableName = expression;

In the statement above, = is the assignment operator, and it assigns a value on the right side to the variable on the left side. It can also re-assign a new value to an existing variable! Some examples are shown below:

let numClasses = 4;

numClasses = 5; // modifies value to 5

numClasses = numClasses - 2; // decreases to 5-2=>3

let totalUnits = 12;

let avgUnitsPerClass = totalUnits / numClasses;

// the above variable equals 12 / 3 => 4

We also have the addition assignment (+=) operator, which is pretty neat way to add a value to an existing variable.

numClasses += 1; // now back equal to 4

// same as numClasses = numClasses + 1, but shorter

For variables with fixed values, we can elect to use const instead.

const CS106S_UNITS = 1; // 1-unit wonder!

const LITERS_IN_A_GALLON = 3.785;

In older JavaScript code, you may encounter the keyword var in the place of let for declaring variables. As a general principle, avoid using it; there's a subtle difference with variable scoping and accessibility (see here if you're curious).

Functions

The general structure for defining a function in JavaScript is

function functionName(list of input parameters){

list of statements in function body

}

You can optionally return a single value (of any type), with a statement of form return expression;

To see this in action, consider the following function which simply adds two numbers together and gives back the result.

function addTwoNumbers(x,y){

let sum = x + y;

return sum;

}

To call or invoke a function in JavaScript, you supply the function name, and pass in values for each input parameter, e.g.,

let sum1 = addTwoNumbers(3,4);

let sum2 = addTwoNumbers(-1, Math.PI);

/

let sum3 = addTwoNumbers(addTwoNumbers(1,2), 3)

As another example, here's a function that converts 🌡️ Celius to Fahrenheit temperatures:

function celsiusToFahrenheit(celsius){

return 9/5 * celsius + 32;

}

let TokyoC = 10;

let TokyoF = celsiusToFahrenheit(TokyoC);

console.log("Tokyo: ",TokyoC,"°C, ",TokyoF,"°F");

Conditional Logic

The comparison operators === and !== check for equality and non-equality conditions, respectively (note three equal signs instead of two). The other operators <,<=,>=,> behave as mathematically expected.

3 === 3

3 < Math.PI

0.999 === 1

JavaScript also has if , else if , and else conditional statements, for a program to behave differently under varying conditions. To see these in action, consider a 🐻 Goldilocks function that takes, as input, the temperature outside, and judges it.

function Goldilocks(fahrenheit){

if (fahrenheit < 32){

console.log("It's too cold outside!");

}

else if (fahrenheit > 90){

console.log("It's too warm outside!");

}

else{

console.log("The weather is just right.");

}

}

Note this function will log that it's "just right" only when fahrenheit is between 32 and 90, i.e. it's at least 32 degrees AND it's at most 90 degrees. Now say, instead, we want a function that returns the boolean true if the temperature is "just right", and false if it's too hot or too cold.

For this, in JavaScript, we can leverage the && operator for logical AND (with the || operator being logical OR, and ! for logical NOT).

function isGoldilocks(fahrenheit){

return fahrenheit >= 32 && fahrenheit <= 90;

}

function isNotGoldilocks(fahrenheit){

return fahrenheit < 32 || fahrenheit > 90;

}

function isNotGoldilocks(fahrenheit){

return !isGoldilocks(fahrenheit);

}

Strings

Strings are an ordered collection of characters, enclosed by quotation marks.

let film = "wizard of oz";

let home = "Kansas";

let s = "";

You can obtain the number of characters by checking the length property, i.e. str.length. Also, character positions in a string are identified by an index, which begins with 0, not 1, and extends up to str.length - 1.

| w |

i |

z |

a |

r |

d |

|

o |

f |

|

o |

z |

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

You can select an individual character via its index by calling name.charAt(index), or simply name[index] with the square brackets notation.

film[0]

film.charAt(1)

film.charAt(6)

film[film.length - 1]

The + operator allows us to concatenate strings, a swanky word for combining strings end-to-end with no intervening characters.

"Dorothly" + " Gale";

“m” + “o” + “v” + “i” + “e”;

Objects

JavaScript objects are akin to Python dictionaries i.e. key-value pairs enclosed in curly braces. Keys are unique strings; values are not necessarily unique, and can be of any data type. As some examples,

let SUNET = {

"bbyan": "Benjamin Bin Yan",

"poohbear": "Jerry Cain",

...

};

let numStudents = {

"cs103": 216,

"cs106A": 500,

"cs106B": 439,

"cs107": 252,

};

We access or lookup values by their keys! To do this, we can use the square bracket notation, e.g.,

numStudents["cs106a"]

numStudents["cs109"] = 283;

numStudents["cs111"] = 320;

numStudents["cs103"] += 50;

If the key is hard-coded in our program (e.g., doesn't change based on an input parameter), we can also use the syntax objectname.keyName, e.g.,

numStudents.cs107

We can check if a key already exists in an object, using an expression of the form keyName in objectName. Say we want a function getStudents (assume it already has access to the numStudents object) which takes a CS course as input, and returns its enrollment if the course exists in the object data, and 0 otherwise. We can write:

function getStudents(course){

if (course in numStudents){

return numStudents[course];

}

return 0;

}

getStudents("cs109")

getStudents("cs1000000")

Checkpoint #1

Complete the function letterToIndex in assignment.js. As a tip, make use of the mapping object it's already been granted access to, and recall how to use keys to lookup values within a JavaScript object.

To get an overall sense for how the Caesar cipher works, you can see the README documentation here.

Arrays

Arrays are an ordered collection of elements of any type, with indices starting at 0 and ending at arr.length - 1, akin to strings.

| "cs106b" |

"math52" |

"english9ce" |

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

We use the square brackets notation to lookup elements via their indices,

let myCourses = ["cs106b","math52","english9ce"];

myCourses[0]

myCourses[1]

myCourses.length

Arrays are mutable and of variable length, meaning that you can add, remove, or change elements within it. The .push() method adds elements to the back of an array, and .pop() removes the element at the back and returns it.

myCourses.push("college102");

console.log(myCourses);

myCourses[1] = "math53";

console.log(myCourses);

let droppedCourse = myClasses.pop();

console.log(myCourses);

We can use .slice(start,end) to take a subarray or contiguous section of an array, beginning at index start and ending one shy of end.

let perfectNums = [6, 28, 496, 8128, 33550336];

perfectNums.slice(0,2)

perfectNums.slice(1,4)

We can also concatenate elements of an array into a single, unified string using the .join() method.

let wordFragments = ["all", "is", "well"];

wordFragments.join(" ")

wordFragments.join(",")

Lastly, we can declare an empty array with [], e.g., let arr = [];.

Checkpoint #2

Complete the function indexToLetter in assignment.js As a tip, make use of the alphabet array, and recall how to access elements in an array via their indices. And as a tip for handling the wrap-around for indices 26 and greater, look at the remainder operator and clock example above (JavaScript Kick-Off section).

Checkpoint #3

Complete the function shiftLetter in assignment.js. Tip: make use of the helper functions you've written for previous checkpoints!

For Loops

For loops—awesome for repeatedly executing a block of code! It'll do so a fixed number of times / iterations. The syntax in JavaScript is more similar to C++/Java than to Python, e.g.,

function sayHelloWorld(numTimes){

for (let i = 0; i < N; i++){

console.log("Hello World!");

}

}

Note that each iteration features a different value of i, the loop counter variable, which we can leverage to loop over the indices of an array or string, or more broadly sequences of integers.

function Factorial(n){

let product = 1;

for (let i = 2; i <= n; i++){

product = product * i;

}

return product;

}

function getSum(array){

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < array.length; i++){

sum += array[i];

}

return sum;

}

getFactorial(5)

getSum([3,1,4,1,5])

If we have an array, we can actually loop directly over its elements (without having to use indices first), using a neat for/of structure, e.g.,

function getSum(array){

let sum = 0;

for (let element of array){

sum += element;

}

return sum;

}

Strings Take II

As the characters within a string are indexed by integers, starting at 0 and ending one short of the string's length (0,1,2,...,str.length - 1), we can conveniently use for loops to iterate over them, e.g.,

function printEachChar(str){

for (let i = 0; i < str.length; i++){

console.log(str[i]);

}

}

function printEachChar(str){

for (let char of str){

console.log(char);

}

}

As a note, strings in JavaScript are immutable, meaning the string data itself (i.e. the characters) can't be changed after declaration. String methods such as concatenation actually create entire new string objects, which we assign to an existing or new variable.

let name = "percy";

name[0] = "m";

name = name + " jackson";

name += "!!";

Consequently, for most string tasks in JavaScript, we have an existing string whose characters we usually loop over, and a new string variable that we build up from scratch.

As an example, consider a function twins which takes an input string and returns a copy of that string with each character repeated once, e.g., "abc"→"aabbcc", minnesota"→"mmiinnnneessoottaa".

function twins(input){

let output = "";

for (let char of input){

output += char + char;

}

return output;

}

let dancingQueen = twins("abba")

Final Checkpoint!

Complete the function encryptCaesar in assignment.js, then check to make sure all Caesar tests pass in the console. As a tip, use a loop! And make use of the helper functions you've just written.

Optional Checkpoints

Vigenère Cipher

Complete the function encryptVigenere in assignment.js. Take a look at the README documentation here to get a sense for how the Vigenere cipher works, and how it's related to the Caesar cipher you've already wrote. To test your cipher, go to the bottom of the assignment.js file, and uncomment the line that reads as:

And you'll see functionality tests appear in the console when you refresh :) Tip: Leverage helper functions you wrote for previous checkpoints!

Breaking the Caesar Code

Now that we can encrypt messages, we also want to know how to decrypt or decode messages that have been encrypted!

A helper function decryptCaesar(ciphertext,shift) is already written for you, great! It decodes an encrypted message ciphertext, but only with an already given Caesar shift between 0 and 25, inclusive.

In practice, we don't know what the shift is, but we do know it's an integer in 0,1,2,...,25. There's only 26 possibilities, which isn't a whole lot!

With this mind, complete the function breakCaesar(ciphertext) in assignment.js, which should loop over every possible shift value, and print out what the decrypted string would be for each one, making calls to decryptCaesar. How you format the printing is up to you! This brute-force approach allows us to manually inspect all the possibilities, and see which one is likely correct, e.g., the one that contains valid English words.

Extra Note: The approach for decryptCaesar, as we may expect, is very similar to encryptCaesar! But instead of shifting each letter shift spaces forward in the alphabet, it shifts them shift spaces backward, e.g., C→A,D→B,Z→X for shift=2). In fact, in the actual code, as a convenience, decryptCaesar actually calls your encryptCaesar function, but with a reversed shift value to reverse the original encryption!

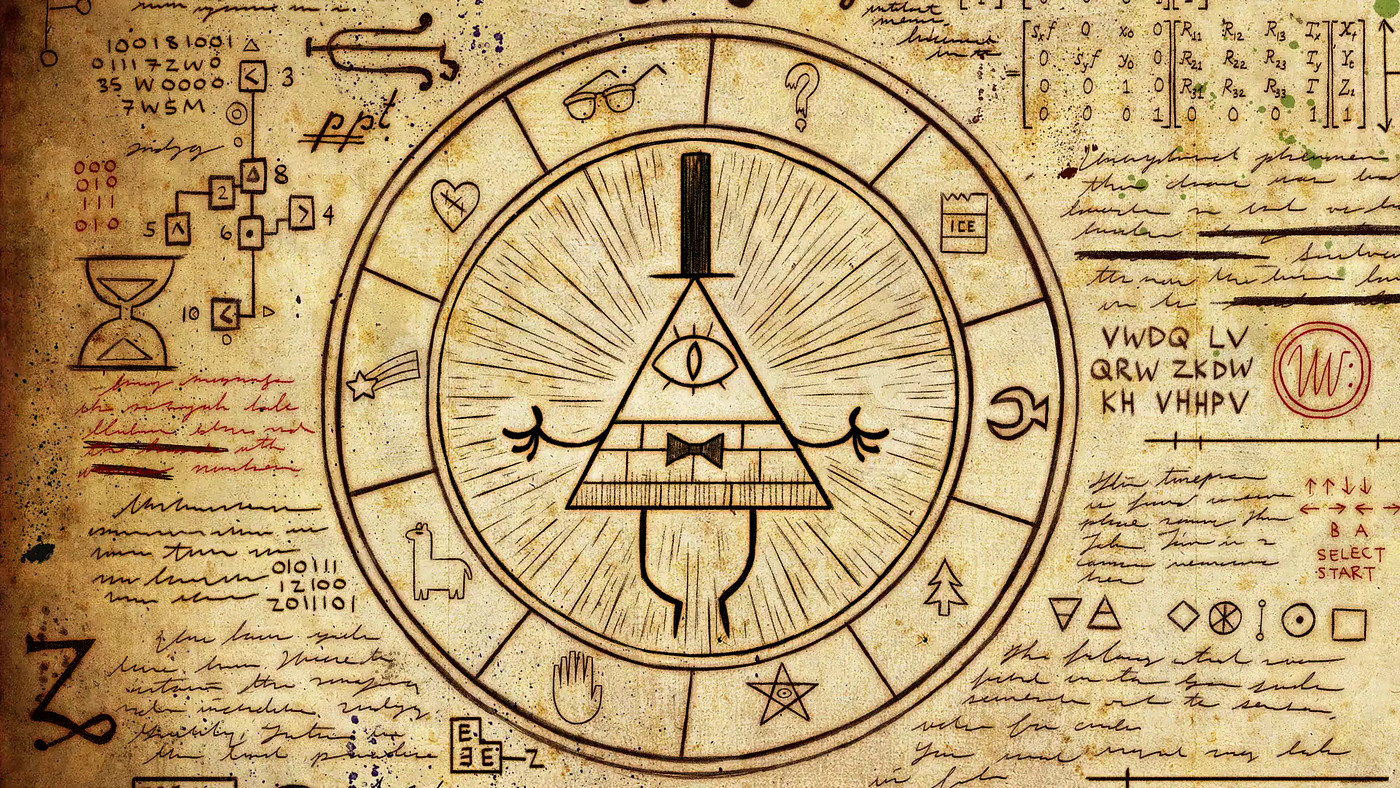

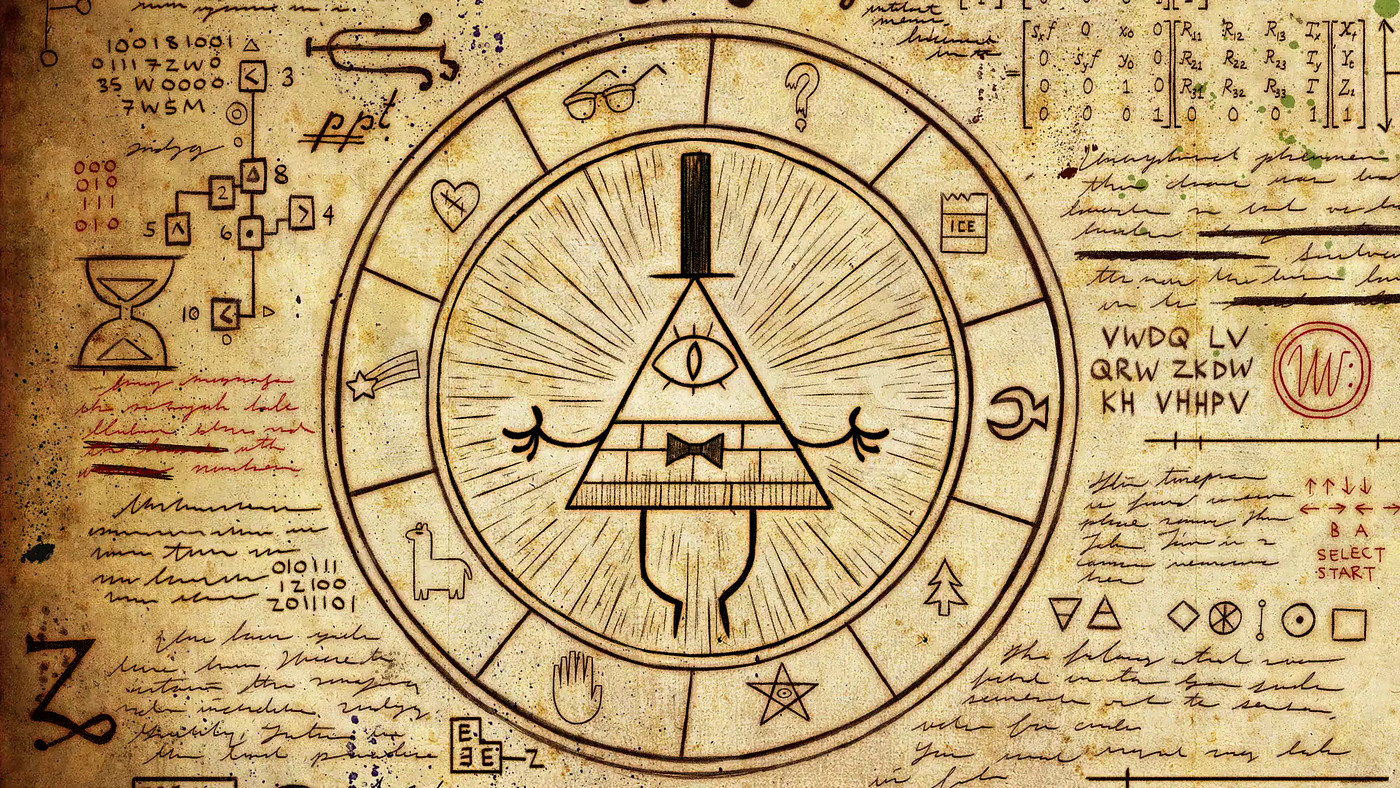

Decrypt some fun messages in Gravity Falls!

The animated TV series Gravity Falls 🌲🌲 (2012-2016) was an endearing fan-favorite on the Disney channel, known for its mischief humor, voice acting, supernatural mystery themes, and, very relevant to us, the ciphers it placed in the end credits for each episode. Most of them were Caesar or Vigènere ciphers! And sometimes, they subtly foreshadowed major events and twists—leading all the way up to the main antagonist, a ruthless dream demon whose name, no kidding, is Bill Cipher. Scary stuff.

Below is a list of ciphers / cryptograms that appear in Gravity Falls. For fun, try to crack as many ciphers as you can! (I promise no spoilers). As a tip, you'll find it useful to adapt your encryptCaesar implementation to handle strings with potentially non-alphabetic characters (spaces, punctuation). Specifically, for any alphabet characters, you'll want to shift them as normal, but for non-alphabetic characters, you'll want to leave them unchanged, e.g.,

"hello world!"→"jgnnq yqtnf!". You can still assume any letter that appears will be lowercase. Let me know if you have any questions!

| Episode |

Cipher Type |

Cryptogram |

| S1 EP1 |

Caesar |

"vwdq lv qrw zkdw kh vhhpv" |

| S1 EP1 |

Caesar |

"zhofrph wr judylwb idoov" |

| S1 EP3 |

Caesar |

"kh'v vwloo lq wkh yhqwv" |

| S1 EP4 |

Caesar |

"fduod, zkb zrq'w brx fdoo ph?" |

| S1 EP5 |

Caesar |

"rqzdugv drvklpd!" |

| S1 EP16 |

Caesar |

"sxehuwb lv wkh juhdwhvw pbvwhub ri doo dovr: jr rxwvlgh dqg pdnh iulhqgv." |

| S1 Finale |

Caesar |

"eloo lv zdwfklqj" |

| S2 EP2 |

Vigènere |

"ooiy dmev vn ibwrkamw bruwll" |

| S2 EP7 |

Vigènere |

""mxngveecw mw slaww sul fpzsk mw sojmrx" |

| S2 Finale |

Vigènere |

"glcoprp googwmj fxzwg" |

For the Vigènere ciphers, you'll want to use the decryptVigenere(ciphertext, keyword) function already written in assignment.js. For each cipher, the keyword will be among this word bank: "cursed","erase","cipher","shifter", "axolotl" (tip: a loop can try all of them quickly)

That's it for the JavaScript tutorial guide, and thank you for reading!!