Assignment 6: HTTP Web Proxy and Cache

This assignment was written by Jerry Cain, with modifications by Philip Levis, Nick Troccoli, Chris Gregg, and Ryan Eberhardt.

This assignment has you implement a multithreaded HTTP proxy and cache. An HTTP proxy is an intermediary that intercepts each and every HTTP request and (generally) forwards it on to the intended recipient. The servers direct their HTTP responses back to the proxy, which in turn passes them on to the client. Here’s the neat part, though. When HTTP requests and responses travel through a proxy, the proxy can control what gets passed along. The proxy might, for instance, do the following:

- Strip requests of all cookie and IP address information before forwarding it to the server as part of some larger effort to anonymize the client.

- Intercept all requests for GIF, JPG, and PNG files and scale them down to reduce transfer time.

- Cache responses to frequently requested, static resources that don’t change very often so it can respond to future requests for the same exact resources without involving the origin servers.

- Redirect the user to an intermediate paywall to collect payment for wider access to the Internet, as some airport and coffee shop WiFi systems are known for.

- Load balance requests across a collection of servers.

Due: Thursday, August 19th at 11:59 p.m. We will accept late submissions with no deduction until Tuesday, August 24th at 11:59p.m., although we advise being careful with your time if you intend to complete Assignment 7, which will be due Friday, August 27th, since we cannot accept late submissions for that.

Getting started

Go ahead and clone the git repository we’ve set up for you by typing:

git clone /usr/class/cs110/repos/assign6/$USER assign6

Compile often, test incrementally and almost as often as you compile, run

./tools/sanitycheck, and run ./tools/submit when you’re done.

If you cd into your assign6 directory, you’ll notice a subfolder called

samples, which itself contains a symlink to a fully operational version

called proxy_soln. You can invoke the sample executable without any

arguments, as with:

$ ./samples/proxy_soln

Listening for all incoming traffic on port <port number>.

The port number issued depends on your SUNet ID, and with very high

probability, you’ll be the only one ever assigned it. If for some reason

proxy says the port number is in use, you can select any other port number

between 2000 and 65535 (I’ll choose 12345 here) that isn’t in use by typing:

$ ./proxy_soln --port 12345

Listening for all incoming traffic on port 12345.

In isolation, proxy_soln doesn’t do very much. In order to see it work its

magic, you should download and launch a web browser that allows you to appoint

a proxy for HTTP traffic. I’m recommending you use

Firefox, since its proxy settings

are easier to configure without setting up a proxy for your entire computer.

Some other browsers don’t allow you to configure browser-only proxy settings,

but instead prompt you to configure computer-wide proxy settings for all HTTP

traffic–for all browsers, Dropbox and/or iCloud synchronization, iTunes

downloads, and so forth. You don’t want that level of interference.

Once you download and launch Firefox, you can configure it as follows:

- Mac: Click Firefox -> Preferences. Then scroll to the bottom to “Network Settings”, click on “Settings…” and activate a manual proxy as shown in the following screenshot.

- PC: Click Tools -> Options. Then scroll to the bottom to “Network Settings”, click on “Settings…” and activate a manual proxy as shown in the following screenshot.

IMPORTANT: Be sure to uncheck “Enable DNS over HTTPS.” Your proxy does not support HTTPS out of the box, and if that option is checked, Firefox will be unable to perform DNS lookups.

You should enter the myth machine you’re working on (and you should get in

the habit of ssh'ing into the same exact myth machine for the next week

so you don’t have to continually change these settings), and you should enter

the port number that your proxy is listening to.

If you’d like to start small and avoid the browser, you can use curl from

your own machine (or from another myth) to exercise your proxy. An example

command might be the following:

curl --proxy http://myth55.stanford.edu:9979 http://icanhazip.com

(This assumes your proxy is listening on port 9979, which is probably not the case – it depends on your sunetID.)

Instructions for off-campus students

As was the case with Assignment 5, if you want to use your browser with the proxy and you’re located off campus (as most of you probably are), you may need to do some extra work.

You have several options:

-

You can use

curlto download web pages, as illustrated above. This is the easiest quick fix, but it will be much nicer for later milestones to have a full-on web browser. -

Connect to the campus network using a VPN; instructions are here. I think this is probably the most convenient option; the VPN doesn’t take long to set up, and will be the easiest to work with.

-

Use an SSH proxy. SSH has a feature that allows us to send traffic to an SSH server, and it will forward that traffic to a web server. If we SSH into a Stanford computer, we can then use that computer to forward web requests to your

proxyserver.- Launch

proxy. Let’s say my server is listening onmyth55port9979. - Open an extra terminal window and

ssh -L 9979:localhost:9979 yourSUnet@myth55.stanford.edu(replacemyth55and9979with whatever host/port you are using). Leave this running on the side. This SSH session will ferry traffic from your computer’s port 9979 to myth port 9979 while it’s open, but it will stop working as soon as the SSH connection is closed. - Configure your browser proxy settings to point to

localhostinstead ofmyth. (Use the port number that your proxy is running on, e.g.9979above.)

This method might be annoying to set up each time you try to connect, but it works if you would prefer to avoid installing the VPN software.

- Launch

Implementing v1: Sequential proxy

Your final product should be a multithreaded HTTP proxy and cache that blocks access to certain domains. As with all nontrivial programs, we’re encouraging you to work through a series of milestones instead of implementing everything in one extended, daredevil coding binge. You’ll want to read and reread Sections 11.5 and 11.6 of your B&O textbook to ensure a basic understanding of the HTTP protocol.

For the v1 milestone, you shouldn’t worry about threads or caching. You should

transform the initial code base into a sequential but otherwise legitimate

proxy. Note that your proxy will only work for HTTP sites for now, not HTTPS

sites – make sure you are testing with HTTP sites! The code you’re starting

with responds to all HTTP requests with a placeholder status line

consisting of an HTTP/1.0 version string, a status code of 200, and a curt

OK reason message. The response includes an equally curt payload announcing

the client’s IP address. Once you’ve configured your browser so that all HTTP

traffic is directed toward the relevant port of the myth machine you’re

working on, go ahead and launch proxy and start visiting any and all web

sites. Your proxy should at this point intercept every HTTP request and

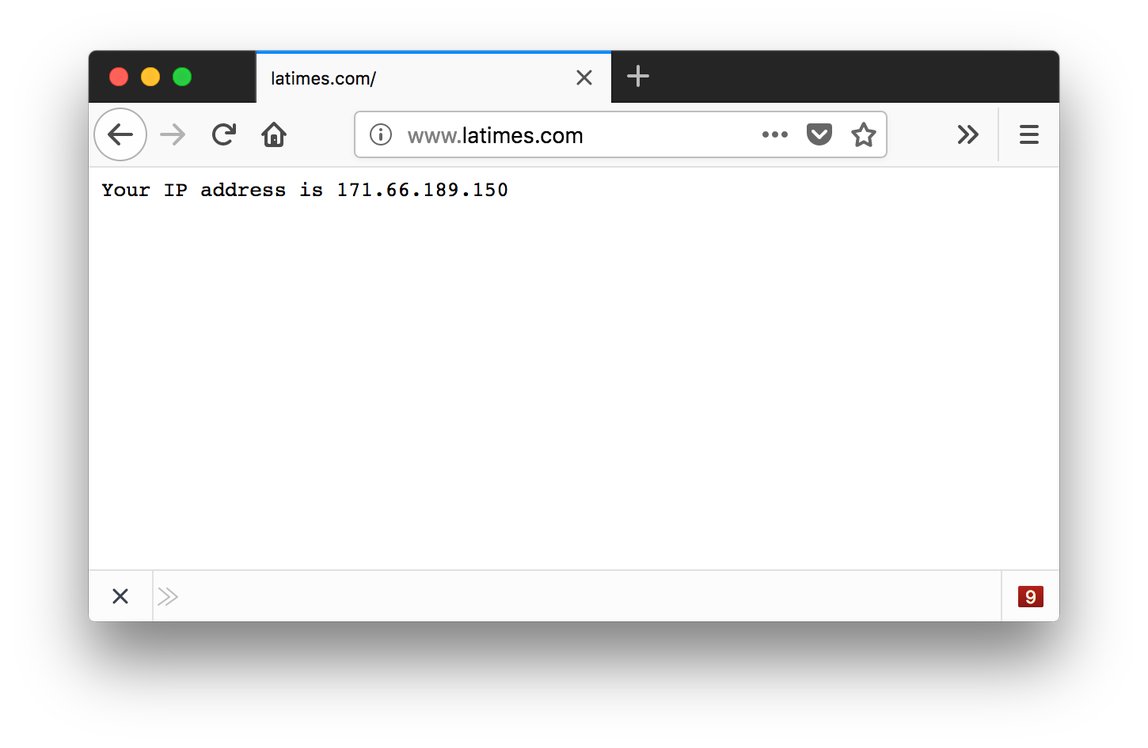

respond with this (with a different IP address, of course):

For the v1 milestone, you should upgrade the starter application to be a true

proxy – an intermediary that ingests GET, POST, or HEAD HTTP requests

from the client, establishes connections to the origin servers (which are the

machines for which the requests are actually intended), passes the HTTP

requests on to the origin servers, waits for HTTP responses from these origin

servers, and then passes those responses back to the clients. Once the v1

checkpoint has been implemented, your proxy application should basically be a

busybody that intercepts HTTP requests and responses and passes them on to the

intended servers.

You’ll do most of the work in this milestone in request-handler.cc. Your code

needs to do the following:

- It needs to read a request from the client. This is already done for you;

serviceRequestpopulates anHTTPRequestobject using data from the client. (Seerequest.hto see what you can do with this.) - It needs to connect to the destination server (e.g.

web.stanford.edu) and send the request to that server. You can start implementing this inhandleGETRequest, although you should eventually decompose, especially as you add support forPOSTandHEADrequests. You will want to usecreateClientSocket, provided inclient-socket.h. - It needs to receive the response from the destination server. You’ll need to

create an

HTTPResponseand use itsingestmethods to populate it with data from the server. - It needs to send the response back to the client. This is somewhat

implemented in the starter code, which creates a default “You’re writing a

proxy!” response and sends that to the client. You’ll want to delete all of

the

response.set*()calls, and instead send to the client the response you received from the origin server. - This should work for

GET,POST, andHEADrequests, although you should start withGETrequests only and then add support for the latter two.

Note that requests/responses are ferried between the client and origin server almost verbatim, but there are a few modifications your proxy needs to make to the request before forwarding it:

-

The request URL should be modified so that when the request is forwarded to the destination server, the destination server receives a path in the format

/some/pathinstead of a full URL such ashttp://destination.com/some/path.When the browser sends a request to your proxy, the request line looks something like this:

GET http://www.latimes.com/books/ HTTP/1.1The

http://www.latimes.comis unusual to include in the request line, but it’s necessary so that your proxy can tell what destination server to connect to. However, when the proxy forwards the request to the destination server, it should send a request line that looks like this:GET /books/ HTTP/1.1We have implemented the

HTTPRequestclass to manage this detail for you automatically (inspect the implementation ofoperator<<inrequest.ccand you’ll see), but you need to ensure that you don’t break this as you start modifying the code base. -

You should add a new request header entity named

x-forwarded-protoand set its value to behttp. Ifx-forwarded-protois already included in the request header, then simply add it again. You will need to modify theHTTPRequestclass in order to add to therequestHeaderstored inside (seerequest.handheader.h). There are many ways to code this up, and you may do so however you see fit. -

You should add a new request header entity called

x-forwarded-forand set its value to be the IP address of the requesting client. Ifx-forwarded-foris already present, then you should extend its value into a comma-separated chain of IP addresses the request has passed through before arriving at your proxy. (The IP address of the machine you’re directly hearing from would be appended to the end). Again, you will need to modify theHTTPRequestclass.

Most of the code you write for your v1 milestone will be confined to

request-handler.h and request-handler.cc files (although you’ll want to

make a few changes to request.h/cc as well). The HTTPRequestHandler

class you’re starting with has just one public method, with a placeholder

implementation.

You need to familiarize yourself with all of the various classes at your

disposal to determine which ones should contribute to the v1 implementation.

Please give yourself adequate time to look through all the starter code, as

there is a lot to piece together. Your implementation of the one public

method will evolve into a substantial amount of code – substantial enough that

you’ll want to decompose and add a good number of private methods.

Once you’ve reached your v1 milestone, you’ll be the proud owner of a

sequential (but otherwise fully functional) proxy. You should visit every

popular web site imaginable to ensure the round-trip transactions pass through

your proxy without impacting the functionality of the site (caveat: see the

note below on sites that require login or are served up via HTTPS). Of course,

you can expect the sites to load very slowly, since your proxy has this much

parallelism: zero. For the moment, however, concern yourself with the

networking and the proxy’s core functionality, and worry about improving

application throughput in later milestones.

Important note: Your proxy doesn’t need to work for HTTPS websites; speaking HTTPS is more complex than what we have presented so far. (Part of the goal of HTTPS is to prevent tampering from middlemen, which is exactly what your proxy tries to do.) HTTP websites are becoming more sparse (a good thing for web security, but bad for debugging purposes). However, many top websites still don’t use HTTPS. See the “Other top sites” section from this site list, and look for sites that are marked as not working on HTTPS or not defaulting to HTTPS.

Implementation and testing tips

- You should add plenty of logging code and print it to standard out. We won’t be autograding the logging portion of this assignment, but you should still add tons so that you can confirm your proxy application is actually moving and getting stuff done.

- Before sending some

HTTPRequest requestto the destination server, you can print it out by typingcout << request. This can be very useful for debugging. Similarly, before you send the response back to the client, you cancout << response. - You can assume your browser and all web sites are solid and respect HTTP request and response protocols. While testing, you should hit as many sites as possible, sticking to (HTTP, not HTTPS) web products. The list of such sites is ever shrinking, since most are switching to HTTPS, but there are still some out there that rely on HTTP. Note: be careful with some sites, as they may use HTTPS for some things. For instance, the CS110 site fetches its stylesheets over HTTPS, so its layout may not look correct. When in doubt, you can see the requests being made by your browser by going to Tools -> Web Developer -> Inspector and clicking the Network tab to view which are HTTP (and thus should be expected to work). Here is a list of sites that still have not transitioned to HTTPS yet (as of the beginning of the assignment):

- We have set up two web pages that you can use to test a page with images and a

POSTrequest: - You do not need to add support for HTTPS in this assignment. You’ll

probably want to avoid web sites like

www.google.com,www.facebook.com,andwww.nytimes.comwhile testing your proxy, since they’re all HTTPS. If, once you get the entire proxy working for submission purposes, you’re interested in HTTPS proxying, you can (optionally – to be clear, this is not required for the assignment) implment theCONNECTmethod and use theHTTPRequestHandler::manageClientServerBridgefunction to implement fullHTTPS. See the note at the bottom of the assignment for details about how to use themanageClientServerBridgefunction. - Your proxy is not required to handle sites that have videos, though if you do

implement

CONNECT(from the last bullet point), it should work (and here is a video test page). - Your

proxyapplication maintains its cache in a subdirectory of your home directory called.proxy-cache-myth<num>.stanford.edu. The accumulation of all cache entries might very well amount to megabytes of data over the course of the next eight days, so you should delete that.proxy-cache-myth<num>.stanford.eduby invoking your proxy with the--clear-cacheflag. - Note that responses to

HEADrequests – as opposed to responses toGETandPOSTrequests – never include a payload, even if the response header includes a content length. Make sure you circumvent the call toingestPayloadforHEADrequests, else your proxy will get held up once the firstHEADrequest is intercepted.

Implementing v2: Sequential proxy with blocked sites, caching

Once you’ve built v1, you’ll have constructed a genuine HTTP proxy. In practice, proxies are used to either block access to certain web sites, cache static resources that rarely change so they can be served up more quickly, or both.

Why block access to certain web sites? There are several reasons, and here are a few:

- Law firms, for example, don’t want their attorneys surfing Yahoo, LinkedIn, or Facebook when they should be working and billing clients.

- Parents don’t want their kids to accidentally trip across a certain type of web site.

- Professors configure their browsers to proxy through a university intermediary that itself is authorized to access a wide selection of journals, online textbooks, and other materials – all free of charge – that shouldn’t be accessible to the general public. (This is the opposite of blocking, I guess, but the idea is the same).

- Some governments forbid their citizens to visit Facebook, Twitter, The New York Times, and other media sites.

- Microsoft IT might “encourage” its employees to use Bing by blocking access to other search engines during lockdown periods when a new Bing feature is being tested internally.

Why should the proxy maintain copies of static resources (like images and JavaScript files)? Here are two reasons:

- The operative adjective here is static. A large fraction of HTTP responses are dynamically generated – after all, the majority of your Facebook, LinkedIn, Google Plus, and Instagram feeds are constantly updated – sometimes every few minutes. HTTP responses providing dynamically generated content should never be cached, and the HTTP response headers are very clear about that. But some responses – those serving images, JavaScript files, and CSS files, for instance – are the same for all clients, and stay the same for several hours, days, weeks, months – even years! An HTTP response serving static content usually includes information in its header stating the entire thing is cacheable. Your browser uses this information to keep copies of cacheable documents, and your proxy can too.

- Along the same lines, if a static resource – the omnipresent Google logo, for instance – rarely changes, why should a proxy repeatedly fetch the same image over and over again an unbounded number of times? It’s true that browsers won’t even bother issuing a request for something in its own cache, but users clear their browser caches from time to time (in fact, you should clear it very, very often while testing), and some HTTP clients aren’t savvy enough to cache anything at all. By maintaining its own cache, your proxy can drastically reduce network traffic by serving up cached copies when it knows those copies would be exact replicas of what it’d otherwise get from the origin servers. In practice, web proxies are on the same local area network, so if requests for static content don’t need to leave the LAN, then it’s a win for all parties.

In spite of the long-winded defense of why caching and blocking sites are

reasonable features, incorporating support for each is relatively

straightforward, provided you confine your changes to the request-handler.h

and .cc files. In particular, you should just add two private instance

variables – one of type BlockedSet, and a second of type HTTPCache – to

HTTPRequestHandler. Once you do that, you should do this:

-

Update the

HTTPRequestHandlerconstructor to construct the embeddedBlockedSet, which itself should be constructed from information inside theblocked-domains.txtfile. The implementation ofBlockedSetrelies on the C++11regexclass, and you’re welcome to read up on the regular expression support they provide. You’re also welcome to ignore theblocked-set.ccfile altogether and just use it.Your

HTTPRequestHandlerclass would normally forward all requests to the relevant original servers without hesitation. But, if your request handler notices the origin server matches one of the regexes in theBlockedSet-managed set of verboten domains, you should immediately respond to the client with a status code of 403 and a payload ofForbidden Content. Whenever you have to respond with your own HTML documents (as opposed to ones generated by the origin servers), just go with a protocol ofHTTP/1.0. You should do this for all request types / HTTP verbs, even ones that aren’t officially supported by your proxy. -

You should update the

HTTPRequestHandlerto check the cache to see if you’ve stored a copy of a previously generated response for the same request. TheHTTPCacheclass you’ve been given can be used to see if a valid cache entry exists, repackage a cache entry intoHTTPResponseform, examine an origin-server-providedHTTPResponseto see if it’s cacheable, create new cache entries, and delete expired ones. The current implementation ofHTTPCachecan be used as is – at least for this milestone. It uses a combination of HTTP response hashing and timestamps to name the cache entries, and the naming schemes can be gleaned from a quick gander through thecache.ccfile.Your to-do item for caching? Before passing the HTTP request on to the origin server, you should check to see if a valid cache entry exist. If it does, just return a copy of it – verbatim! – without bothering to forward the HTTP request. If it does not, then you should forward the request as you would have otherwise. If the HTTP response identifies itself as cacheable, then you should cache a copy before propagating it along to the client. Note: you should only cache or check for requests in the cache for requests that have already had their headers updated, as specified in version 1. So make sure that e.g. the

x-forwarded-forandx-forwarded-protoheaders are in any requests before they are cached!What’s cacheable? The code I’ve given you makes some decisions – technically off specification, but good enough for our purposes – and implements pretty much everything. In a nutshell, an HTTP response is cacheable if the HTTP request method was

GET, the response status code was 200, and the response header was clear that the response is cacheable and can be cached for a reasonably long period of time. You can inspect some of theHTTPCachemethod implementations to see the decisions I’ve made for you, or you can just ignore the implementations for the time being and use theHTTPCacheas an off-the-shelf.

Once you’ve hit v2, you should once again pelt your proxy with oodles of

requests to ensure it still works as before, save for some obvious differences.

Web sites matching domain regexes listed in blocked-domains.txt should be

shot down with a 403, and you should confirm your proxy's cache grows to

store a good number of documents, sparing the larger Internet from a good

amount of superfluous network activity. (Again, to test the caching part, make

sure you clear your browser’s cache a whole bunch.)

Implementation and testing tips

- Here is a page that you can use to test caching (you should get the stale time on subsequent loads if your proxy is caching correctly): click here

- You can check

blocked-domains.txtto see a list of websites that should not load under your proxy. You can usecurl -vto ensure that the proper status code is being returned by your proxy. - If you want to impose a maximum time-to-live value on all cacheable

responses, you can invoke your proxy with

--max-age <max-ttl>. If you go with a 0, then the cache is turned off completely. If you go with a number like 10, then that would mean that cacheable items can only live in the cache for 10 seconds before they’re considered invalid.

Implementing v3: Concurrent proxy with blocked sites and caching

You’ve implemented your HTTPRequestHandler class to proxy, block, and cache,

but you have yet to work in any multithreading magic. For precisely the same

reasons threading worked out so well with your Internet Archive program,

threading will work miracles when implanted into your proxy. Virtually all

of the multithreading you add will be confined to the scheduler.h and

scheduler.cc files. These two files will ultimately define and implement an

über-sophisticated HTTPProxyScheduler class, which is responsible for

maintaining a list of socket/IP-address pairs to be handled in FIFO fashion by

a limited number of threads.

The initial version of scheduler.h/.cc provides the lamest scheduler ever:

It just passes the buck on to the HTTPRequestHandler, which proxies, blocks,

and caches on the main thread. Calling it a scheduler is an insult to all

other schedulers, because it doesn’t really schedule anything at all. It just

passes each socket/IP-address pair on to its HTTPRequestHandler underling and

blocks until the underling’s serviceRequest method sees the full HTTP

transaction through to the last byte transfer.

One extreme solution might just spawn a separate thread within every single

call to scheduleRequest, so that its implementation would go from this:

void HTTPProxyScheduler::scheduleRequest(int connectionfd,

const string& clientIPAddress) {

handler.serviceRequest(make_pair(connectionfd, clientIPAddress));

}

to this:

void HTTPProxyScheduler::scheduleRequest(int connectionfd,

const string& clientIPAddress) {

thread t([this](const pair<int, string>& connection) {

handler.serviceRequest(connection);

}, make_pair(connectionfd, clientIPAddress));

t.detach();

}

While the above approach succeeds in getting the request off of the main thread, it doesn’t limit the number of threads that can be running at any one time. If your proxy were to receive hundreds of requests in the course of a few seconds – in practice, a very real possibility – the above would create hundreds of threads in the course of those few seconds, and that would be bad. Should the proxy endure an extended burst of incoming traffic – scores of requests per second, sustained over several minutes or even hours, the above would create so many threads that the thread count would immediately exceed a thread-manager-defined maximum.

Fortunately, you built a ThreadPool class for Assignment 5, which is exactly

what you want here. You should leverage a single ThreadPool with 64 worker

threads, and use that to elevate your sequential proxy to a multithreaded one.

Given a properly working ThreadPool, going from sequential to concurrent is

actually not very much work at all.

Your HTTPProxyScheduler class should encapsulate just a single

HTTPRequestHandler, which itself already encapsulates exactly one

BlockedSet and one HTTPCache. You should stick with just one scheduler,

request handler, blocked set, and cache, but because you’re now using a

ThreadPool and introducing parallelism, you’ll need to implant more

synchronization directives to avoid any and all data races. Truth be told, you

shouldn’t need to protect the blocked set operations, since the blocked set,

once constructed, never changes. But you need to ensure concurrent changes to

the cache don’t actually introduce any races that might threaten the integrity

of the cached HTTP responses. In particular, if your proxy gets two competing

requests for the same exact resource and you don’t protect against race

conditions, you may see problems.

Here are some basic requirements:

- You must, of course, ensure there are no race conditions – specifically, that no two threads are trying to search for, access, create, or otherwise manipulate the same cache entry at any one moment.

- You can have at most one open connection for any given request. If two threads are trying to fetch the same document (e.g. the HTTP requests are exactly the same), then one thread must go through the entire examine-cache/fetch-if-not-present/add-cache-entry transaction before the second thread can even look at the cache to see if it’s there.

You should not lock down the entire cache with a single mutex for all

requests, as that introduces a huge bottleneck into the mix, allows at most one

open network connection at a time, and renders your multithreaded application

to be essentially sequential. You could take the

map<string,unique_ptr<mutex>> approach that the implementation of oslock

and osunlock takes, but that solution doesn’t scale for real proxies, which

run uninterrupted for months at a time and cache millions of documents.

Instead, your HTTPCache implementation should maintain an array of 997

mutexes, and before you do anything on behalf of a particular request, you

should hash it and acquire the mutex at the index equal to the hash code

modulo 997. You should be able to inspect the initial implementation of the

HTTPCache and figure out how to surface a hash code and use that to decide

which mutex guards any particular request. A specific HTTPRequest will

always map to the same mutex, which guarantees safety; different

HTTPRequests may very, very occasionally map to the same mutex, but we’re

willing to live with that, since it happens so infrequently.

I’ve ensured that the starting code base relies on thread safe versions of

functions (gethostbyname_r instead of gethostbyname, readdir_r instead of

readdir), so you don’t have to worry about any of that. (Note your assign5

repo includes client-socket.[h/cc], updated to use gethostbyname_r.)

Implementation and testing tips

- Here is a page that you can use to test multithreading: http://ecosimulation.com/cgi-bin/longAccessTime.py?time=4. The “time=4” means that the request should take 4 seconds to complete. If you want it to take longer, increase that number.

- Be sure to run TSan (

./proxy_tsan) and ASan (./proxy_asan) while you try loading a bunch of pages to ensure that your code is free of data races and memory errors. - Your

proxyapplication should, in theory, run until you explicitly quit by pressing ctrl-C. A real proxy would be polite enough to wait until all outstanding proxy requests have been handled, and it would also engage in a bidirectional rendezvous with the scheduler, allowing it the opportunity to bring down theThreadPoola little more gracefully. You don’t need to worry about this at all.

Congratulations!

When you complete this assignment, we hope that you feel very proud of what you’ve accomplished! It’s genuinely thrilling to know that all of you can implement something as sophisticated as an industrial-strength proxy, particularly in light of the fact that just a few weeks ago, we hadn’t even discussed networking yet.

Optional v4: Adding Proxy Chaining

Some proxies elect to forward their requests not to the origin servers, but instead to secondary proxies. Chaining proxies makes it possible to more fully conceal your web surfing activity, particularly if you pass through proxies that pledge to anonymize your IP address, cookie jar, etc. A proxied proxy might also rely on the services of an existing proxy while providing a few more–better caching, custom strikesets, and so forth–to the client.

The proxy_soln we’ve supplied you allows for a secondary proxy to be

specified, as with this:

myth61:$ ./samples/proxy_soln --proxy-server myth63.stanford.edu

Listening for all incoming traffic on port 39245.

Requests will be directed toward another proxy at myth63.stanford.edu:39245.

Provided a second proxy is running on myth63 and listening on port 39245, the

proxy running on myth61 would forward all HTTP requests–unmodified, save for

the updates to the "x-forwarded-proto" and "x-forwarded-for" header

fields–on to the proxy running on myth63:39245, which for all we know

forwards to another proxy!

We actually don’t require that the secondary proxy be listening on the same port number, so something like this might be a legal chain:

myth61:~$ ./samples/proxy_soln --proxy-server myth63.stanford.edu --proxy-port 12345

Listening for all incoming traffic on port 39245.

Requests will be directed toward another proxy at myth63.stanford.edu:12345.

In that case, the myth61:39245 proxy would forward all requests to the proxy

listening to port 12345 on myth63. If

the --proxy--port option isn’t specified, then the proxy assumes the its own

port number also applied to the secondary.

The HTTPProxy class we’ve given you already knows how to parse these

additional --proxy-server and --proxy-port flags, but it doesn’t do

anything with them. You’re to update the hierarchy of classes to allow for the

possibility that a (or several) secondary proxy is being used, and if so, to

forward all requests (as is, except for the modifications to the

"x-forwarded-proto" and "x-forwarded-for" headers) on to the secondary

proxy. This’ll require you to extend the signatures of many methods and/or add

methods to the hierarchy of classes to allow for the possibility that requests

will be forwarded to another proxy instead of the origin servers. You should

also update your error checking when your proxy connects to a server to print a

different error message if you cannot connect to a proxy vs. just a regular

server. In other words, if you’re trying to forward a request on to its

destination server but can’t, print something like “Failed to connect to server

XXX”. IF you’re trying to forward a request on to the next proxy in the chain

but can’t, print something like “Cannot forward request to specified next proxy

XXX”.

Additionally, you’ll want to update the implementation of operator<<(ostream& os, const HTTPRequest rh) so that the full URL is passed along in the first

line of the entire request when forwarding to another proxy, since even

secondary proxies need to see the protocol and host, just like the primary one

does. If you notice a chained set of proxy IP addresses that lead to a cycle

(even if the port numbers are different), you should respond with a status code

of 504. You should check for cycles by seeing whether x-forwarded-for

contains the client IP already. This doesn’t cover some edge cases, like if

the cycle is only formed by the final proxy and does not result in an infinite

loop (e.g. mythA:1111->mythB:1111->mythA:2222->destination) but that handling

requires a proxy finding its own IP address, which you don’t have to do.

For fun, we’re supplying a python script called run-proxy-farm.py, which can

be used to manage a farm of proxies that forward to each other. One you have

proxy chaining implemented, open the python script, update the HOSTS variable

to be a list of one or more myth machine numbers (e.g. HOSTS = [51, 53, 57, 60]) to get a chain of proxy processes running on the different hosts. Note

that you cannot run the python script to test for cycles in chains; you will

have to set that up manually. (If you want to use run-proxy-farm.py to test

for cycles, you’ll need to modify it to support that).

Optional: Implementing CONNECT for https:// access

If you would like to support HTTPS websites, which are the dominant sites on

the web these days (for good

reason),

you will need to support the CONNECT request, which is similar to a GET

request. However, this request is relevant only for the proxy(ies) between the

client and the destination server, and not actually intended for the

destination server itself. You must ultimately open a connection to the

destination server (without sending anything), and then have a 200 OK response

sent back to the client. Once you have handled this, you should flush the

input stream and then pass both the input stream and output stream to the

manageClientServerBridge(iosockstream& client, iosockstream& server)

function. The input stream is the stream to the client, and the output stream

(that you created to forward the request) is the stream to whom you are

forwarding onto. Simply calling the manageClientServerBridge function is all

that you should need to do to fully complete the CONNECT request. If you are

forwarding to another proxy, you must instead forward the CONNECT request and

call manageClientServerBridge.