How to Run a Student Discussion Section

This is a quick primer for how to run a discussion section. Each of you will be responsible for leading one in-class discussion. This along with your participation in the discussions led by other students will account for 30% of grade. This shouldn't be onerous. It is intended to make it easy for you to get the most out of what this course has to offer, and hopefully it will give you an idea of how similar student-guided discussions are routinely conducted in research labs that include undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs and faculty from multiple disciplines all of whom have different backgrounds and specialties.

Outline of the Basic Selection and Execution Process

Sign up for a topic. We will send you a link to a spreadsheet where you can enter your preferences.

No more than four students will be assigned any given topic. Early topics will have at least three.

If there is more than one person assigned your topic, get in touch with them and start planning.

I'll send you examples of what you're expected to do and suggestions for reading and watching1.

A week before the date for your discussion, send out links to your required reading & viewing.

Familiarize yourself with how to use Zoom to lead your discussion, and coordinate with Rafael.

Example Topic Preparation, Materials and Readings

The topics for discussion sections are listed below. In this section, we provide some sample material that you could use if you are assigned either the first topic, actor-critic learning, or the third, action selection. The action-selection section builds on actor-critic learning and together they provide the basis for understanding the complex role of the basal ganglia in governing behavior in mammals and humans in particular.

The five topics listed under the heading "Functional Components" are ordered taking into account the dependencies between them, and together they provide the foundation for the rest of the class. I'll ask students to sign up for these five first and after we have completed the first two or three, we can select additional topics from the "Basic Representations" and "Fundamental Problems" lists in any order, since they have few if any dependencies constraining the order in which we discuss them.

In the 2018 instantiation of the class, Randy O'Reilly gave a great introduction on computational cognitive neuroscience and distributed representations. Randy worked with Jay McClelland and other members of the was part of the PDP (Parallel Distributed Processing) group at CMU where completed his PhD. He co-authored several influential papers on complementary learning systems [12, 13, 15].

In addition to his earlier talk, we met with Randy this summer for nearly two hours discussing the finer points of his PBWM (Prefrontal Cortex Basal Ganglia Working Memory —) theory [16]. We'll go over that meeting in covering the executive control topic in a subsequent discussion section, and you can find Randy's 2018 class discussion here.

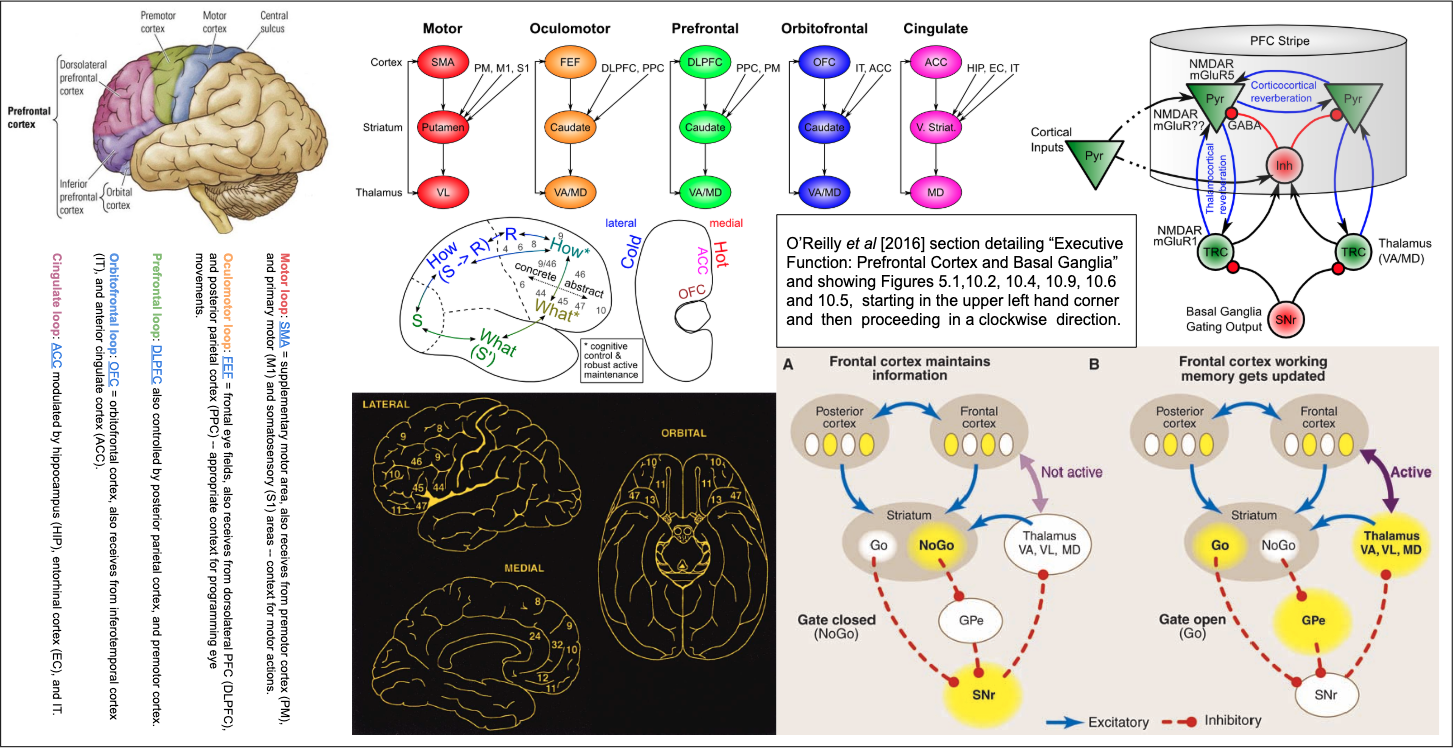

Matt Botvinick's talk on the prefrontal cortex as meta reinforcement learning [23] is at the heart of the actor-critic topic and covered well in Matt's talk in class. For the PBWM, discussion it would make sense for the students to read the section entitled "Executive Function: Prefrontal Cortex and Basal Ganglia" in O'Reilly et al [18] — see Figure 2.

Take a look at these short — less than ten minutes each — videos on the Brain Inspired YouTube Channel:

There are similar videos covering the same material on the Khan Academy website. Here are two examples:

| |

| Figure 1: In the paper [3] that Chaofei, Gene, Meg and I wrote last year, we fleshed out what we learned from the class in the Spring quarter and then expanded the material during the Fall to include four content boxes of the sort used in survey articles to focus on key concepts and provide additional detail. Each of Chaofei, Gene and Meg did a literature search on a general topic and then compressed what they learned to highlight specific technical content relevant to the rest of the paper. In developing presentation material for your discussion sections, you should try to do the same albeit in a substantially shorter span of time than we had to write the paper. Your task is made easier since your goal is to convey a basic understanding of the neuroscience and related technology, and there are plenty of online tutorials, lectures and papers that you can use. | |

|

|

The student-guided discussions last year were a success in that students learned more and learned it more quickly and thoroughly than if they had passively listened to an invited speaker. In addition to providing an overview and channeling expert content by alternating between showing video and providing their own explanations, student teams set the agenda by specifying papers to read prior to class and exchanged email with the experts providing content to answer questions related to their work.

The team consisting of Tyler Benster, Julia Gong, Jerry Meng, John Mern, Megumi Sano and Paul Warren reviewed Oriol Vinyal's presentation from 2018, elicited questions from the students and Oriol provided answers in return. In addition to student guided-discussions, last year we also had new invited talks from: Jessica Hamrick, Adam Marblestone, Loren Frank, Michael Frank and Peter Battaglia, there were several new speakers.

An alternative approach to finding speakers that is less intrusive than asking someone to go out of their way to produce a new talk tailored precisely to our interests, is for us to find interviews, public talks at conferences or invited speakers at Google, Stanford and other venues. For example, Alex Graves gave an excellent talk on neural Turing machines at a symposium on deep learning held at Microsoft Research that was recorded and posted on YouTube, and there is a more recent, condensed overview at the NIPS 2016 Symposium on Recurrent Neural Networks and Other Machines that Learn Algorithms.

| |

| Figure 2: The text Computational Cognitive Neuroscience [18] covers most of the topics that we have selected for class this year and serves as a primary reference to simplify explanations in the discussion sections. Here we see a sequence of graphics taken from the O'Reilly text that would work well for the discussion section on the Prefrontal Cortex Basal Ganglia Working Memory (PBWM) model. For example, in explaining this model to the rest of the class, you could sequence through the graphics using them as visual talking points, starting from the upper center and continuing in a clockwise direction around the figure shown above. | |

|

|

List of Topics in Order of Presentation

Functional Components:

actor-critic learning (basal ganglia and reinforcement learning) — April 14, Tuesday

episodic memory (hippocampus and differentiable neural computers) — April 16, Thursday

action selection (frontal cortex, striatum, thalamus and working memory) — April 21, Tuesday

executive control (prefrontal cortex, planning complex cognitive behavior) — April 23, Thursday

prediction-action cycle (reciprocally connected motor and sensory systems) — April 28, Tuesday

Basic Representations:

relational learning (recognizing, learning and using relational models) — April 30, Thursday

graph networks (learning, reasoning about connections between entities) — May 5, Tuesday

interaction networks (learning and reasoning about dynamical systems) — May 7, Thursday

analogical reasoning (combining existing models to create new models) — May 12, Tuesday

perception as memory (attention, affordances, anticipatory behaviors) — May 14, Thursday

Fundamental Problems:

algorithmic abstraction (when we generalize skills creating hierarchies) — May 19, Tuesday

catastrophic forgetting (when we forget old skills in learning new ones) — May 21, Thursday

partial observability (when the system is a higher-order Markov process) — May 26, Tuesday:

List of Representative Papers

O'Reilly [17] — An Introduction to Distributed Processing in the Brain

Botvinick [24] — The Prefrontal Cortex as Meta Reinforcement Learning

O'Reilly [16] — Prefrontal Cortex Basal Ganglia Working Memory (PBWM)

Daw, Frank, Gershman [4, 6] — Revisiting Reinforcement Learning and Episodic Memory

Graves, Weston [7, 25] — Memory Networks and Differentiable Neural Computers

Fuster, Botvinick [5, 2] — Fuster's Hierarchy and the Perception-Action Cycle

Stachenfeld et al [21] — Hippocampus as Predictive Model in Higher-level Cognition

Hamrick [8] — Relational Inductive Bias for Physical Constructions

Battaglia [1, 11] — Relational Inductive Biases, Learning and Graph Networks

Sanchez [19] — Graph Networks as Learnable Physics Engines for Inference

Hill et al [9] — Analogies by Contrasting Abstract Relational Structure

Mnih, Kaiser, Silver, Vinyalls [10, 22, 20, 14] — What have Atari, Go and StarCraft taught us about AI?

References

1 Raphael and I will help you find a suitable video lecture featuring one or more of the researchers working on your assigned topic. Everyone in the class will be expected to watch / review this prior to class and / or read one or more of the suggested relevant research papers.