Colombia:

Tomorrow’s Vietnam

By Jameel Johmson & Kristen Carothers

EDGE Spring, 2003

Securing economic opportunity,

domestic and abroad, has always been an integral aspect of U.S. foreign

policy. Dating back to the early 20th

century, when Teddy Roosevelt wielded his “Big Stick,” the United States first

began to establish a presence in Latin America. It assumed the role of “Big Brother,” with the primary objective

of creating an atmosphere viable to American economic growth in the

region. Roosevelt’s policy was

significant in that it developed the precedence for the United States to police

not only its neighbors, but the entire globe as well. This political stance was aimed to safeguard American interests,

ideological and material, but later set the stage for conflict as it was

challenged and even further propelled by the spread of communism. The United States became directly embroiled

in international conflicts, typified by American military presence in Vietnam

during the 1960s and in Latin America in the 1980s. However, with the end of the Cold War, the fear of the growth of

communism subsided and today, Latin American countries specifically struggle

with the perils of the drug trade. It

not only has etched a web of money laundering, violence, and corruption, but

has also emerged as a global epidemic, particularly as it finances the activities

of domestic guerilla groups and international terrorist forces. It presents a potential threat to American

security and peace; however, it is not the sole reason for the current U.S.

involvement in Latin America. The

United States government is still haunted by the shadows of American bloodshed

in Vietnam and predominantly, the backlash it has elicited from the general

public. In order to avoid further

scrutiny, the government is unwilling to admit their complete justification for

the escalation of military forces in Latin America, particularly in the nation

of Colombia. The existence of the drug

trade is emerging as a pretext for increased U.S. interference in Colombia that

is a detrimental force, fueling further violence and worsening human rights

conditions. It is clear that Colombia

is tomorrow’s Vietnam.

The devastating battle with drug

trafficking has wrought far-reaching effects in Colombia. However, to understand the severity of

turmoil and poverty that the drug trade perpetuates, it is necessary to also

address the nation’s additional economic, political, and social ills. Historically, Colombia has been one of Latin

America’s most stable countries, experiencing steady economic growth from the

1930s and onto the mid 1990s. Even through

Latin America’s troubled times of the 1980s, Colombia maintained its financial

fortitude with its economy growing at an average annual rate of 3.5

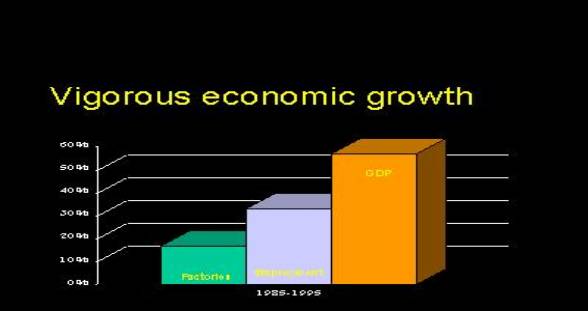

percent. The subsequent graph

demonstrates this period of vigor.

World Bank Group: http://www.worldbank.org/nipr/lacsem/columpres/sld003.htm

The

illustration shows the growth of the annual GDP (orange bar) along with the

contributions from the number of factories (green bar) and rate of employment

(blue bar) from the years of 1985 to 1995.

The Colombian GDP averaged 4.6% increase, while its manufacturing

establishments rose by almost 17% and employment grew by 33%. However, the prosperity that characterized

the Colombian economy began to end in the mid 1990s, reaching a severe low in

the 1999 recession. Harvesting of

Colombia’s key export, coffee, was depressed and its prices plunged, in which

this decline was one of the early and ominous signs of Colombia’s financial

fate. Its demise continued as the

annual GDP tumbled by 4%, while unemployment was stuck at a record high of 20%

and 55% of the population (40,349,388) were well below the poverty line (Wall

Street Journal, September 23, 1999).

This dismal state of Colombia’s financial market helped blanket the

nation in uncertainty, creating an atmosphere that embraced any prospect of

riches, further cementing the supremacy of the drug trade.

Distant from the country’s sagging

economy, narcotic growth and trafficking represents a $400 billion worldwide

industry with its roots implanted throughout Colombia. Unlike earlier years, when the cultivation

of coca (cocaine derived plant) remained low in the country, troubled economic

times have spurred increased coca growth in the 1990s that has thrust Colombia

forward as the world’s largest coca producer.

For instance, in 1998, Colombia had 93,000 hectares (232,500 square

acres) of land under coca and opium poppy cultivation, also generating 69,000

full-time jobs (The Colombian Economy after 25 Years of Drug Trafficking,

Ricardo Rocha). Coca growth has

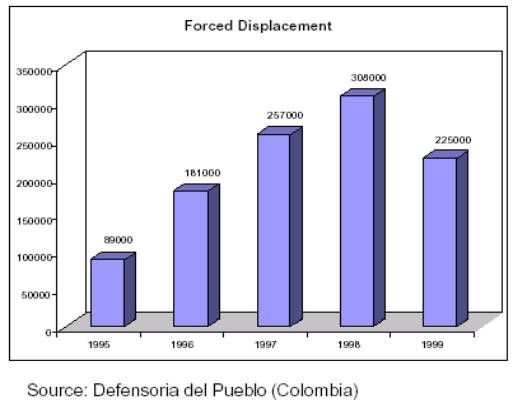

attracted many laborers, primarily attributed to the agricultural decline that

forced the displacement of numerous workers as depicted in the following

graph.

http://www.mama.coca.org/feb2002/drugtrade.pdf

The graph shows the

number of unemployed workers for the years between 1995 and 1999. It highlights a severe facet of Colombia’s

economic struggles that has strengthened its foundation in narcotic growth and

trade. Another startling aspect of the

drug trade’s influence is that in comparison to the decline in coffee exports,

the drug trafficking has generated greater revenue as reflected in the

subsequent graph (1982-1996).

http://www.mamacoca.org/feb2002/drugtrade.pdf

As

seen in the graph, by 1986, the illegal narcotics trade had emerged as an

overwhelming source of income, nearly doubling the amount of finances brought

in by legal coffee exports. The trend

persists through the 1990s; a disturbing pattern demonstrating the considerable

extent that Colombia was entrenched in the drug trade. Equally alarming, Colombia’s share of the

cocaine market rose from 50% (1981) to 85% (1999), accounting today for about

$7.5 billion of yearly income (CIA World Fact book). This money profited from the narcotics trafficking is cleverly

interwoven into the Colombian economy, also providing the drug mafia with

additional security. It was said that,

“one could hardly go past a major development without being told that laundered

money financed it. This included hotels, nightclubs and shopping centers,

exclusive ranches and mansions” (Colombian Cartels, www.pbs.org).

The following graph demonstrates the Colombian drug trafficking income

as a percentage of the nation’s GDP ($250 billion).

“The

Colombian Economy after 25 Years of Drug Trafficking”, Ricardo Rocha

The

illustration points to the financial control that the drug trade has gained;

yet in 1998, their income of $7.5 billion was only 3% of Colombia’s total GDP

($250 billion). It reflects the

relatively diminutive effects that drug trafficking has directly on the fraught

Colombian economy. However, the

overwhelming and worldwide influence of the drug trade can never be overlooked

as “the estimated turnover of $400 billion has the power to corrupt almost

anyone” (World News, R.E. Kendall, Secretary-General of Interpol). Drug money’s vast influence in political

iniquity has become another symptom of the ills that afflict Columbia.

Notably,

positioned at the forefront of this “narco-democracy,” have been the crime

cartels: Medellin and Cali. The

Medellin cartel, led by Pablo Escobar, was the first of Colombia’s powerful

drug organizations that fed cocaine to the United States and abroad throughout

much of the 1980s. During that time,

the Medellin was also thought to be responsible for the murder of countless political

officials, police, prosecutors, judges, and journalists. Unfortunately, the Medellin demise in the

early 1990s only facilitated the rise to power of their rivals, the Cali

cartel, led by the Rodriguez Orejuelas brothers. After replacing the Medellin cartel, the Rodriguez brothers flooded

the markets and today, they now supply 80 percent of the cocaine flowing into

the United States and Europe (The Cali Connection, www.ccsf.edu). It

is a stark reflection of the power they possess.

In

addition, Colombia suffers from a lack of national cohesion and the political

fragmentation contributes to the inefficacy of their government to deal with

the drug trade. Each different state

fights to affirm its own regional independence, failing to form a united body that

effectively opposes the trade and growth of narcotics. At the same time, allegations continue to

mount, asserting that the Colombian government has been too lenient on the drug

cartels. For example, the Rodriguez brothers (Cali Cartel) received the near-maximum

penalty of 23 years when convicted, but are likely to be released after six (The

Cali Connection, www.ccsf.edu).

Many experts consider this a result of an arrangement between the

Colombian government and the brothers to avoid their extradition to the United

States, where they would face harsher penalties. More disturbing, DEA agents still believe that the Rodriguez

brothers continue to manage the Cali cartel right from their prison cells (Colombian

Cartels, www.pbs.org). The shortcomings of the Colombian

government’s ability and desire to more effectively confront drug trafficking

has created further uncertainty within the nation, particularly with its

condemnation by the United States in 1996.

It intensified Colombia’s loss of political legitimacy in domestic and

international forums. This has

furthered the staggering loss of public confidence that has now been compounded

with fear as the social atmosphere of Colombia has been enveloped by the

actions of guerrilla and paramilitary groups.

In earlier years, these

independently armed forces first appeared in response to their bitter

dissatisfaction with the government and burning desire for change. However, economic hardships had pressed them

to embrace the lure of riches and life of violence associated with the drug

trade. The most notable of the

guerrilla groups have been the Revolutionary Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the

National Liberation Army (ELN). In

opposition to the Colombian oligarchy of the 1960s, FARC was established in

1964, as the military wing of the Colombian Communist Party. It was comprised mainly of disenchanted

farmers and destitute laborers, aligned with the Soviet movement and

Moscow-line communists. On the other

hand, although ELN was also formed in 1964, it was greater influenced by the

Cuban revolution and was composed mostly of students and Colombian university

graduates (Colombian Labyrinth, Rabasa and Chalk). The divergence between the groups was

attributed to the tensions between Cuba and Moscow over strategy in Latin

America; though, the goals of both insurgents were to enact social change,

diminishing the unjust disparity in wealth among Colombian citizens. These aims were consistent for both groups

and involvement in drug trafficking was mostly carried out by paramilitaries,

who were privately armed “self-defense” groups. However, during the early 1980s, the cultivation of coca became a

dominant economic activity and in opposition to the paramilitaries and

government, the guerilla groups of FARC and ELN also began to promote and

protect the coca crops. In this period,

the vicious relationship among guerilla groups, paramilitaries, and the Colombian

government was developed that later would create much turmoil in the country.

Crowned

as the guardians of the narcotics trade, the guerilla and paramilitary

insurgents pierce and rip at the delicate social fabric of Colombia,

perpetuating violence and feelings of trepidation as they struggle for control

of the drug market. These groups offer

protection by overseeing each stage of drug trafficking from its cultivation on

the farm to its manufacture in the labs, and to its movement in the hands of

smugglers. It is a service that rewards

the insurgents with profitable gains in revenue. For instance, in 1998, guerillas and paramilitaries received 620

billion pesos ($551 million) solely from the drug trade. FARC specifically has a breakdown of fees (gramajes)

such as $5263 for protection per laboratory, $2631 for security of landing

strips, and $4210 for protection of coca fields per square acre (Colombian

Labyrinth, Rabasa and Chalk). In

turn, these groups used the derived money to finance armed conflicts and

primarily support the growth of their military forces.

Today,

the guerillas and paramilitaries are comprised of approximately 9,000 to 12,000

armed combatants, involved in numerous illegal activities. These include bombings, murders,

kidnappings, extortions, hijackings, as well as conventional military action

against Colombian political and economic targets. FARC and ELN are responsible for 20 to 30 percent of all of the

kidnappings that take place in the world.

For example, in March of 1999, the FARC executed three U.S. Indian

rights activists on Venezuelan territory after it kidnapped them from Colombia

(Colombian Labyrinth, Rabasa and Chalk). Foreign citizens are often the targets of FARC kidnappings, but

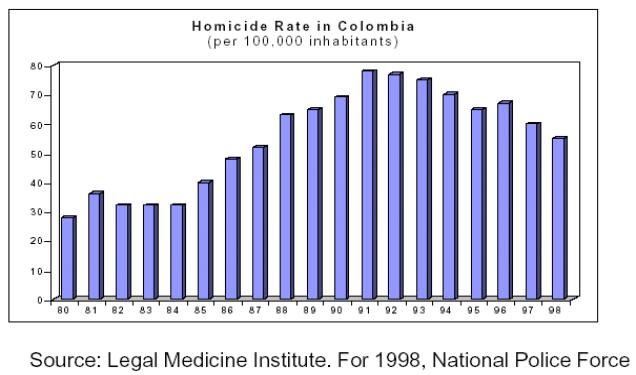

no local citizen is immune from the violence that the insurgents promote. For instance, the homicide rate in Colombia

has more than doubled over the past 20 years with the growing presence of

guerrillas and paramilitaries. These

groups, trying to gain control, commit “social cleansing” murders or limpiezas,

slaying those deemed misfits or suspected of cooperating with the opponent (Colombian

Labyrinth, Rabasa and Chalk).

http://www.mamacoca.org/feb2002/drugtrade.pdf

Bibliography

1. Klare,

M. “The Real Reason for U.S. Aid to

Colombia.” News Wire.

2. Wall

Street Journal, September 23, 1999.

3. Rocha,

Ricardo. The Colombian Economy after

25 Years of Drug Trafficking.

4. World

News

5. Flenker,

Cassandra. Colombia: To Save a

Democracy.

6. www.pbs.org.

Colombia’s Samper and the Drug Link.

7. www.ccsf.edu. The Cali Connection.

8. Rabasa

and Chalk. Colombian Labyrinth.

9. McManimon,

Shannon. Militarizing the Drug War.

10. Herman,

E. Globalization and Instability:

The Case of Colombia.

11. http://warpeace.org. The Folly of the U.S. Drug War.