Zimbabwe’s Age Old Issue:

Land Reform

By:

Marie Holzapfel

Juan Camacho

Introduction:

Even in an environment of imperfect markets, economic theory is very clear on the fact that one-time redistribution of assets can be associated with permanently higher levels of growth. The World Bank 2001 World Development Report confirmed that inequality in the distribution of land ownership is associated with lower subsequent growth(Birdsall 1997; 2001), and redistribution has been shown to be good for growth(Bardhan 1997; Aghion 1999). For example in China as compared to India, equal distribution of land ownership is shown to have made a significant contribution to human development indicators(Burgess 1998). There is evidence from throughout the world that redistributive land reform helps reduce poverty, increase efficiency, and establish the basis for sustained growth (Beasly 1998; Deninger 1998; Deninger April 2000). Many land reforms are often implemented in a way that reduces their possible impact on equity and efficiency. Zimbabwe has implemented a land reform program with the aim of taking land from rich white commercial farmers and redistributing it to poor and middle-income landless black Zimbabweans. However, this process of land distribution has caused concern amongst many in the international community. The reported breakdown of law in the process has caused serious acts of violence against farm owners and farm workers who have been involved in the land distribution process. The need for land reform in Zimbabwe is generally acknowledged, but the process in which it is taking place must be altered.

Land and People of Zimbabwe

To understand the impact of land resettlement on the Zimbabwean people, some background on the demographics is necessary. Located in central southern Africa, Zimbabwe is a completely landlocked country of an estimated 13.7 million people and 150,803 square miles of land. Composed of mostly high plateau with higher central plateau and mountains in the east, rainfall varies from about 70 inches in the Highlands to less that 25 inches in the south. While seven percent is arable land and thirteen percent is permanent pastures, about 57 percent is either unusable or part of their extensive national park system (iafrica.com). The majority of the unusable land is either mountains in the east, or designated as ‘tribal lands.’ More specifically, the land not productive enough for large commercial farms, and is therefore designated as communal land for the native Africans to subsistence farm on (Figure 1). Their economy is therefore dependent on the land and subjected to extreme fluctuations during times of drought.

On the fertile land, the commercial farms produce enough to support Zimbabwe as majority agricultural economy. As the breadbasket of the south, they provide corn as the chief food source for many other African countries, and other products include cotton, sorghum, peanuts, wheat, sugarcane, soybeans, coffee, and tea’s. This critical position in the food economy gives the commercial farms strength in the government. More importantly, they also gain power from bringing in huge profits for their exports of tobacco to many Asian countries, such as China.

The rest of the GDP is composed of profits from a large dairying industry, and a variety of mineral resources, such as gold, nickel, asbestos, tin, iron, chromite, copper, coal, diamond and platinum. Among Zimbabwe’s industrial products are iron and steel, cement, foodstuffs, machinery, textiles and consumer goods, which provide 24.4 percent of the GDP(Group 2001).

Other tensions arise surrounding land ownership since less than one percent of the population is white, but they control over half of the productive land. About 98% of the population is African, with the Shona group predominant(Group 2001). Since independence in 1980, the European population of Zimbabwe fell to under 100,000. White land ownership and government participation has influenced culture in many forms as well. The official language of Zimbabwe is English, with Shona and Ndbele being the prominent African languages. About half the population practices a blend of Christian and indigenous religions. The urban population of the major cities of Bulawayo, Chitungwiza, Gweru, and the capital, Harare, constitute thirty-six percent of the total population(Group 2001).

History of British Control to

Self Rule[1]

Land has been a source of political conflict for Zimbabwean’s since the London Missionary Society established a mission to the Ndebele in 1861, and the first British and Boer traders began to moved into Zimbabwe. Colonization of the region was obtained by Cecil Rhodes to promote commerce with a charter from the British South Africa Company in 1889. This territory in central Zimbabwe was soon taken over by Leander Starr Jameson in 1893 with fighting at Fort Salisbury. Native populations of Ndebele and Shona then staged unsuccessful revolts against the British in 1896-1897. Soon after, settlers and the British government renewed the company’s charter. The renewal enabled settlers to reject proposals for incorporation into the Union of South Africa, and instead elected to make Rhodesia a self governing colony under the British Crown on September 12, 1923.

The Europeans continued to dominate land, trade and government. Even when a new constitution adopted in early 1960’s, African political participation was limited. The conservative Rhodesian government of prime minister Ian Smith then declared independence from Britian in November 1965. Britian proclaimed this an act of rebellion, but did nothing to take back the region by force. Thus, Rhodesia became a republic on March 2, 1970, and Britain and Rhodesia reached an accord that provided gradual increases in African political participation, though without any guarantee of eventual black majority rule. White Rhodesians seized control of the vast majority of good agricultural land, leaving black peasants to scrape a living from marginal “tribal reserves” (Figure 2).

Throughout the 1970’s, land inequity fueled two nationalist organizations to commit guerrilla warfare against the white majority government of Rhodesia. The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) led by Robert Mugabe was based in Mozambique, and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) was based in Zambia. Prime minister Smith declared a state of emergency and a period of repression followed as the vicious apartheid regime tortured civilians and bombed refugee camps in neighboring Zambia and Mozambique. Smith’s attempts to crush the opposition were based on preserving the privileges of 7,000 white farmers and their families, and their 35 million acres, which was more than half of Zimbabwe’s most productive land. Smith appealed to right-wing politicians in the United States and Britain in a failed attempt to gain recognition of the Republic of Rhodesia. Unsupported, he was forced to negotiate with three black leaders to reach an “internal settlement” and an interim coalition government. In 1979, a white-only referendum approved a new constitution and renamed the country Zimbabwe-Rhodesia.

Though this struggle for independence killed over 25,000 people, it was the beginning of self rule for Zimbabwe. Further pressure from Britain established a new constitution, a cease-fire and a legally independent, democratically governed Zimbabwe. In the elections of April 1980, Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF (Patriotic Front) party won and he became the first prime minister of the Republic of Zimbabwe. The changeover was not complete though, as whites still held 20 seats in the assembly and 10 seats in the senate. More importantly, they maintained the economic privilege and imperialist ownership of the largest mining and industrial enterprises.

With an internal struggle between ZANU and ZAPU still existing, Mugabe ousted ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo from his cabinet and began five years of political repression, human rights abuses, mass murders, and property burnings. A peace accord was finally negotiated in 1987, and ZAPU merged into the ZANU-PF party as Nkomo returned to the government.

Recent History of Land Reform

While ZANU and ZAPU-PF warred over governmental control from 1980-1987, the continuing colonial mentality of the landlords was evident from the fact that they carried on voting for the former party of apartheid, the Rhodesian Front. In 1985, 4,500 white farmers owned 50% of the country’s productive land, while the 4.5 million peasants lived in communally owned rural areas known as “tribal lands,” i.e. least fertile, where the black population was forced to live during the colonial era. The Commercial Farmers Union (CFU) of white farmers still had the bower to block many initiatives for rural relocation. They controlled 90% of all agricultural production, paid 1/3 of the country’s salaries, and exported 40% of the country’s goods (Ahmed 2002).

It was not until Mugabe was elected president in 1987 and then reelected in 1990 that he abandoned the formerly Marxist principles of ZAPU-PF began to implement land reform and the government into a one-party state in 1990. In 1980 through the Lancaster House Agreement, Britain had promised 40 million pounds to resettle 162,500 families through the process of “willing buyer, willing seller” policies that did not allow any government land acquisition. This was not a success, and by 1985, fewer than 30,000 families had been resettled and many farms designated for sale and resettlement were lying derelict (Encyclopedia 2002). Once the Lancaster House Agreement expired in 1990, Parliament began drawing up and passed the Land Reform Act in 1992, which was popular amongst the majority of workers and peasants, but evoked strong protest form the white-dominated Commercial Farmers Union. This Act gave the government strengthened powers to acquire land for resettlement, subject to the payment of “fair “compensation fixed by a committee, including powers to limit the size of farms and introduce a land tax. By 1992, the angry CFU manipulated the government by causing enough financial losses to force Mugabe to implement a Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) to reform the economy in favor of imperalist interests “to liberalize the economy.” In other words, Mugabe was forced to halt land reform and increase expenditure on education and health due to the lack of governmental funds and high rates of inflation. The stock markets reflected the no longer ideal conditions for foreign capitalists to make a fast buck by exploiting Zimbabean labor and mineral resources through the devaluation of Zimbabwean currency.

Whites began loosing their strength in the government during the multiparty elections of 1995, as ZANU-PF won nearly all seats against a weak and fragmented opposition. Thus land reform continued, and 40,000 families were resettled by 1999, making the total resettled area 3.5 million hectares. Though this seemed to be a great success for the black government, it was hindered by a 33% decline in mining production, a 40% fall in gold output, and a soaring rate of HIV infection, 1/3 of the population was infected by 1997 (Ahmed 2002).

While it is common for government budgets to fluctuate and countries to be in debt, Zimbabwe’s land reform policies brought direct scrutiny on the government and became a focus western world opposition. Britain, the United States, and other European countries upset with Mugabe’s land reform policies began to propagandize the increasing problem of food shortages as means of vocally disapproving and hindering land reform. Resettlement had increased African landholdings, but it drastically cut productivity as the area under maize barely increased from 96,000 ha in 1993 to 100,000 ha six years later(Encyclopedia 2002). In the lands resettled by 1999, only 100,000 ha were planted with maize in that year, compared with the 1.1 million ha in the traditional communal areas and 207,000 ha in the commercial areas. With starvation on the forefront, the Zimbabwean government was unable to design a coherent economic strategy that included land reform and satisfied the Commonwealth. It was through the starvation issue that the world’s attention was brought onto Zimbabwe, as the government struggled to continue land reform while incurring threats of withdrawal of food aide, foreign investments and sanctions.

Though successive Zimbabwean finance ministers committed themselves to restoring macroeconomic stability, their ability has been severely constrained by commitment to the new land resettlement strategy, Fast Track Land Reform 2000, and outside environmental and political forces. Formerly the bread basket in the southern African region, Zimbabwe was devastated by Cyclone Eline, which destroyed granaries, crops, livestock and homesteads with floods. In 2001, agriculture provided 17.6 percent of the GDP, and was predicted to drop 12 percent in the following year (Group 2001). Then in 2002, Zimbabwe suffered one of the worst droughts in human history as the government scrambled to feed over 7.8 million people and a stated of disaster was declared in all communal lands, resettlement and urban areas (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the GDP began its fall of 27% in four years, 1999-2002 (Group 2001).

Due to economic setbacks and growing debt from the World Bank, the election of 2000 was close between the ruling ZANU-PF party led by Mugabe and a new Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) party. Capitalizing on the fact that land reform remains a powerful issue, Mugabe’s slogan was “Land is the Economy; Economy is the Land.” In the face of the challenge represented by the MDC and other increasingly outspoken critics of the government, President Mugabe and the ZANU-PF party responded after the election with a call for a radical land redistribution policy and a new wave of land occupations for members of the War Veterans Association. An amendment to the constitution, 16A, significantly extended the grounds on which land could be compulsorily acquired and absolved the government from providing compensation, except for improvements. There had been some violence before 2000, but after the Referendum, the level exploded. At least forty-eight people died of political violence during 2001 (Forum 2001). According to human rights groups, harassment of opposition activists and intimidation of farm workers escalated through 2001 to 2002 (Figure 4).

Specifically, the Fast Track Land Resettlement Program took effect in July 2000, stating that it would acquire more than 3,000 farms for redistribution. Between June 2000 and February 2001, a total of 2,706 farms, covering more than six million hectares were listed in the official government journal for compulsory acquisition (Ministry of Lands 2001). According to the Commercial Farmers Union, more than 1,600 commercial farms were taken over by black settlers led by war veterans in the course of 2000. Some of the occupations were accompanied by violence (Figure 5). By January 2002, up to 4,874 farms were listed for acquisition, totaling 9.23 million hectares of land (Programme 2002). As of April 8, 2002, some 3,000 had already been turned over, enabling the resettlement of about 202,000 landless black Zimbabweans. The final order to turn over the remaining 5,000 farms recently came through. Most recently, white farmers were ordered by the Government of Zimbabwe off those farms no later than August 9, 2002. Those who failed to do so would be arrested, and many were (Figure 6).

From the government's point of view, the position has been that 12.5 million blacks could not achieve economic goals as long as a white community of about 60,000 controlled so many large tracts of the country's most productive land and dominated the country's industry and commerce. While that might well be true, the reality of agriculture in Zimbabwe has been that the white commercial farms have a solid performance record of being highly productive, they employed many black workers, and they were number two behind the tourism sector for bringing in sorely needed foreign exchange. Farms beginning with 200 workers (300 family members total), and one white owner were turned over to two program models. Under A1, “the decongestion model for the generality of landless people with a villagized and self-contained variant,” 160,000 beneficiaries came from among the poor. The A2 model was aimed at creating a group of small to medium scale black indigenous commercial farmers (Figure 7). By 2002, about 1,000 commercial farms had closed operations completely, while some continued to produce relatively normally, though investment in infrastructure and planting was greatly reduced(Encyclopedia 2002). There is also a concern that taking large sophisticate farms and then sub-dividing them into plots to give to people without the means to manage them properly is a disaster for the agricultural economy. The land distribution problem is not a trivial one, especially compacted by the southern Africa region experiencing drought and famine.

Elections of 2002

In 2002, the presidential elections, which received much attention throughout the world, were held on March 9-11. The Zanu-PF incumbent president Robert Mugabe won with 56.2% of the votes, and the main opposition party, MDC candidate, Morgan Tsvangirai came in second with 42% of the votes, the best achievement of any opponent has ever made against Mugabe (Africa News March 28, 2002). In Harare and Chitungwiza, the presidential election was held simultaneously with the municipal elections for the two mayors and councilors for those cities (Africa News March 28, 2002). In this election, the candidates from the MDC won the mayoral top posts with a large majority, suggesting that Mugabe is more popular than his party. Mugabe ran on a platform that developed sharp attacks against Britain as the former colonial power attempted to control Zimbabwe through the MDC. Previously, few took the threat of neo-colonialism seriously, but during the campaign, the image of Mr. Tsvangirai as Tony Blair’s “tea-boy” became ingrained in voters’ minds (Africa News March 28, 2002). Another aspect of the election was the ongoing crisis in the country, with the general feeling of the people with regard to the drought and food shortages was Mugabe, who had saved the people in previous droughts, is best suited to feed them now (Africa News March 28, 2002). Although not a specific area of the platform, rather it loomed in the background, was Mugabe’s land reform. It was an ongoing program, which had seen hundreds of thousands of families resettled on land formerly owned by white farmers. This was popular in all rural areas, including MDC strongholds. On the creation of jobs, Mugabe was less convincing simply because he was the incumbent president, when so much unemployment was evident. The main objective of the MDC, the main opposition party, was to remove Mugabe from the presidency and accused Mugabe of clinging to power at all cost (Africa News March 28, 2002). All other programs were overshadowed by this call of removal. They promised the revival of the economy, blaming the current government for the severe economic recession the country is passing through (Africa News March 28, 2002). However, the public remained largely unconvinced that Mr. Tsvangirai knew how to our economic fortunes around.

Zimbabwe prides itself as the second longest running multiparty democracy in Africa. With five strong candidates in the field, the rules of the election are: free and peaceful campaigning; freedom of the ballot; total secrecy of the ballot; transparency and integrity of the voting process; and acceptance of the result by the winners and losers (Africa News March 28, 2002). However, there was the charge that free campaigning was inhibited by violence and intimidation by supporters of Mugabe. The death toll of 14 in the two months preceding the elections were unacceptable, although this was a decrease from 40 during the parliamentary elections in 2000 (Africa News March 28, 2002). By regional standards, this is regrettably the norm, for in South Africa, Tanzania, Nigeria, Uganda and Algeria experienced similar or worse political violence. Before the elections, the Western Press had alleged that Zimbabwe might not invite international observers, however this was false with organizations from all over the world taking part in the elections (Africa News March 28, 2002). The following organizations and governments were invited: The Organization of African Unity/African Union (OAU/AU); The Southern Africa Development Community (Sadc); The Common Market for East and Southern Africa (Comesa); The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS); Non-Aligned Movement (NAM); The Commonwealth (excluding the UK); Joint ACP/EU (excluding the UK); The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People of the US (NAACP); and Countries invited separately, such as, Nigeria, South Africa, United States, Japan and Norway (Africa News March 28, 2002).

The reports of the various observers were split between those that found the elections free and fair and those that did not. The first group of observers, made up of the Independent Zimbabwean observer team, South African Development Community, the Commonwealth Observer Group, the Norwegian observer group, the United States observer group and the Japanese observer group, among others found that the violence and intimidation prevented voters from freely expressing their will (Africa News March 28, 2002). There were many incidents of harassment, rape, malicious damage to property and the general breakdown in the rule of law throughout the election process. The chairman of the independent Zimbabwean team stated, “there is no way these elections could be described as substantially free and fair. Tens of thousands of Zimbabweans were deliberately and systematically disenfranchised of their fundamental right to participate in the governance of their country” (Agence France Press 2002). The second group of observers made up of the OAU/AU, Nigeria, Namibia, Zambia, Malawi, China, among others generally approved of the election. The head of the OAU observer team stated, “on the basis of observations made during the voting, verification and counting process on the ground and objective realities, the OAU observer team wishes to state that in general the elections were transparent, credible, free and fair” (Agence France Press 2002). The Zambian President Mwanawasa stated, “As chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and president of a friendly neighbor, I congratulate President Mugabe on his re-election. I appeal to the losers to accept the decision of the people of Zimbabwe and help the process of reconciliation and development. At the same time, I appeal to the international community and observers to respect the will of the people of Zimbabwe” (Agence France Press 2002).

Civil Rights in Zimbabwe

In June 1999, President Mugabe set up a 400 member constitutional review commission to review the independence constitution which some people described as a “cease fire agreement” (Africa News April 12, 2002). Since its adoption in 1980, the constitution has been amended 14 times, with civil society organizations attempting to reform it numerous times. The review commission produced a draft, which many opposing groups described as a grand design by President Mugabe to perpetuate himself in power. There were specific criticisms of the new constitution. Human rights activists say the Bill of Rights is weak. The unions warn the right to strike is curtailed. Women’s groups say it does not recognize equality between men and women. Farmers worry about a clause allowing compulsory land acquisition without compensation. Amnesty international says torture is not outlawed. Journalists say press freedom and freedom of speech are compromised. (Africa News April 12,2002)

These civil rights abuses continued in the 2002 elections, when the Mugabe regime took further steps to control the media. The Public Order and Securities Act was introduced, which aimed at barring foreign journalists from working as correspondents in Zimbabwe and imposed heavy fines and jail terms for news stories that the government consider inflammatory. The police were given sweeping search and arrest powers to uphold the law. The law was seen through on October 23, 2002, when Geoff Nyarota, editor-in-chief of the “Daily News” was charged for allegedly publishing a story that undermines the publics’ confidence in the Zimbabwe Republic Police (Media Institute of S. Africa 2002). The story reported that youth, who were members of the MDC, were arrested and tortured by police in Harare. This was witnessed by one of the youth’s mothers and another first hand witness (Media Institute of S. Africa 2002). With stories such as this one occurring and others unheard, the passage of the law caused international outcry. The European Commissioner for External Affairs statement seemed to represent the feelings of many, “We are profoundly disappointed that the Zimbabwe Parliament has passed this law, which represents a fundamental attack on media freedom” (Africa News April 12, 2002).

Problems with Current Land Reform Program

The human rights violations have not only been reported in the political process but within the fast track process of land redistribution as well. Eye witness testimony collected by Human Rights Watch in July 2001 confirmed reports collected by journalists and other human rights organizations reporting violence that had taken during land occupations (Human Rights Watch 2002). The Commercial Farmers’ Union, representing largely white farm owners, reported at least 829 “violent or hostile” incidents had taken place on commercial farms up to the end of September 2001 (Human Rights Watch 2002). As has been widely reported, war veterans and associated Zanu-PF militia, both supporters of Mugabe, have occupied commercial farms while intimidating, assaulting, and in some cases killing white farm owners. According to human rights groups and the Commercial Farmers Union, at least seven farmers have been killed in political violence since the beginning of 2000 (Human Rights Watch 2002). Most farmers that have been targeted are prominent supporters of the MDC and their farms were not even listed for acquisition of the government. Another common practice with the white farmers is the extortion of money, with the implied threat of violence behind the demands for money (HRW). However sadly throughout this process, most victims of the violence have been the poor farm working Zimbabweans. In June 2000, the National Employment Council for the agricultural industry (a tripartite body of government, employers, and unions) reported that as a result of the farm occupations, at least 3,000 farm workers had been displaced from their homes, twenty-six killed, 1,600 assaulted, and eleven raped (Human Right Watch 2002). More recently the attacks on farm workers have seemed to continue as reported by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum noting 4 deaths and numerous assaults during 2001 (Human Rights Watch 2002). The reason for these repeated attacks on farm workers is again because of their political affiliation with the MDC. In many areas, it seems that farm workers have been targeted for violence in order to deprive the white farm owner of numerous potential allies who have a stake in keeping their jobs and might therefore support the farm owner in resisting the current government (Human Rights Watch 2002). The latest reports from human rights groups have noted continued violence connected with farm occupations. Some have noted a shift away from commercial to the communal areas and towns by early 2002, and a UNDP technical team commented that “acts of lawlessness on large-scale commercial farms now appear to be decreasing” (Human Rights Watch 2002). However, the government’s involvement has not ceased with human rights groups reporting that the police and army have at best failed to take action against the alleged perpetrators of violent crimes and in some cases have actively assisted illegal actions.

Along with the numerous reports of violence with the process of land redistribution, there are numerous other problems: the party political control of access to the forms for applying to land and partisan discrimination in the allocation of plots; and the general exclusion of farm workers from the benefits of land redistribution (Human Rights Watch 2002). The underlying problem seems to be that although there is an official structure for allocating land, in most cases the land is informally distributed by war veterans, who require the recipient to show loyalty to the Zanu-PF. The process is being carried out so rapidly that it has superseded legal procedures causing uncertainty with those that have received plots (Human Rights Watch 2002). Others who want land have not done so because they do not have the resources to farm the land and the government provides very little support to the new farmers. This absence of legal security and assistance to the new farmers could leave them vulnerable to hunger and displacement. Many development organizations that have been following the crisis in Zimbabwe have noted that the disruption to commercial agriculture caused by fast track resettlement has endangered food security in Zimbabwe. In January 2002, a United Nations Development Program (UNDP) technical report on the fast track program noted that the program is “affected by cumbersome consultations and decision-making processes involving numerous district, provincial and central government actors…Problems of weak capacity and poor coordination have led to numerous errors in processing the acquisition of properties” (Human Rights Watch 2002). The UNDP reported that the farms listed for resettlement have been properties totally unsuitable for the purpose, including land flooded under dams, land already resettled, or land currently used for industrial purposes (Human Rights Watch 2002). Production on some commercial farms has continued, where settlers have adopted a pragmatic approach to farming, however the CFU estimated that 31 percent of farms were experiencing total or partial work stoppages in late September 2001 (Human Rights Watch 2002). By January 2002, about 1,000 commercial farms had closed operations completely with the farm owners leaving or the farm being occupied by militia, who would not allow them to farm (Human Rights Watch 2002). The few farms that are producing relatively normally are experiencing a reduction in the investment of infrastructure and planting. In December 2001, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warned that “the already tight food situation has deteriorated as a result of reduced cereal production and general economic decline…705,000 in rural areas are at risk of food shortage. In addition, 250,000 people in urban areas are experiencing food difficulties due to a sharp increase in food prices, while some 30,000 farm workers have lost their jobs and are left without means of assistance” (Human Rights Watch 2002). The Commercial Farmers’ Union believe that close to 250,000 head of cattle, 20 percent of the national commercial herd, had been destocked by 2001, and that over 1.6 million hectares of grazing land had been burnt out, while commercial maize planting was down from 150,000 hectares in the 1999/2000 season to 45,000 hectares in the next season (Human Rights Watch 2002). Tobacco, one of Zimbabwe largest export crop, has similarly been affected. These problems have added to the food shortages already generated by the preceding period of drought. In January 2002, the first consignment of donated maize arrived, usually a maize exporter, and the World Food Program began emergency food distribution in February 2002. However, this was not the first support the international community had given Zimbabwe in recent times.

Role of the International Community

Zimbabwe received financial assistance for land reform during the 1980s and 1990s from various governments, however conditions were put on how the money could be used. The British government had given 44 million pounds for a “land resettlement grant” and budgetary support to the government, from 1988 to 1996 (Human Rights Watch 2002). However in 2000, the British government stated that it was not “convinced that the Zimbabwe government has a serious poverty eradication strategy nor that it is giving priority to land reform to help the poor of Zimbabwe” (Human Rights Watch 2002). The World Bank, another key donor, has acknowledged that the Economic Structural Adjustment Plan for Zimbabwe, its recommendation in 1991, had damaging social consequences. The Bank noted that the reforms under ESAP “could certainly not be regarded as a roaring success, with the percentage of households classified as poor rose from 40 percent in 1991 to over 60 percent in 1995” (Human Rights Watch 2002). The U.S. repeatedly condemned political violence and the breakdown of the rule of law, passing the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Bill in 2001. This ordered U.S. representatives to oppose extensions of any loans to Zimbabwe by the international financial institutions and authorized the president, in consultation with foreign governments, to take action against the individuals responsible for political violence and the breakdown of the rule of law. In 2002, the U.S. imposed sanctions similar to the E.U. on the Zimbabwe government. The donor community also raised various problems with the way in which the funds provided for the program were distributed, such as the recipients that received a large portion of the commercial farmland under the land reform program were a number of senior political leaders. The U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan questioned Zimbabwe’s approach to land reform and said the land reform had to be credible, legal and required adequate compensation to those whose land was being expropriated (Human Rights Watch 2002). In the UNDP report in early 2002 concluded that: “while the political philosophy and socio-economic rational of the Fast Track land reform and resettlement program as defined by the Government of Zimbabwe remain sound, the current scope of the Fast Track represents and over-reach of the original objectives as stated by the Government. In addition, the manner in which the program is being pursued, while legal because of the many changes in the law, has not provided any scope for formal debate either among elected officials, or among those who will lose and those who will benefit” (Human Rights Watch 2002). In January 2002, Secretary-General Annan stated that he “encourages the Government of Zimbabwe to implement fully and faithfully the actions its has promised to take, including ensuring freedom of speech and assembly, admitting international observers, investigating political violence and scrupulously respecting the rule of law” (Human Rights Watch 2002).

Recommendation

The colonial patterns of expropriation established ownership patterns in which white farmers possess large, fertile farms while black rural dwellers barely subsist, must be struck down. There is an urgent need to change the unequal and race based patterns of land occupation; but the fast track land program lays down an infrastructure for rural violence and intimidation that subordinates development plans to political ends. New kinds of hardship and insecurity are being created for the intended beneficiaries of land reform, the rural Zimbabweans. While the international world has focused on the plight of white farm owners and on the consequences of illegal expropriations of land for property rights and the economic situation, it is poor rural, black people who have suffered most from the violence that has accompanied the fast track process. Thus, the Zimbabwe government must alter the Fast Track Resettlement Program by adding to independent review boards to oversee the process, and making the program transparent in accordance with the law. The first review board should be a Zimbabwean land commission, established by law, to resolve conflicts over land allocation, including conflicts caused by occupation of land in violation of the procedures established by the law. The members of the board shall be Zimbabweans experienced in land reform issues that are free of state or party interference. The board shall be adequately resourced and there should be a right of appeal to the regular courts. In addition, there shall be an independent and impartial review of the performance of the fast track process by the United Nations Development Program, in order to identify problems with the program, especially with regard to political selection of beneficiaries and propose mechanisms for resolving these problems in the future. There shall also be international support, both financially and with Human Rights groups monitoring the process. The land reform program will continue to break the farms into small and medium enterprises with better organization, which will ensure greater productivity. The farms themselves shall be completely African run and owned, starting with the farming and ending with the selling of the products in the markets throughout the world. This will require Zimbabwe to put more emphasis on higher education, possibly sending students abroad to learn best business practices. However, the government shall strive for a strong educational system that focuses on farming techniques and the business aspect within farms. There shall be extensive monetary support from groups such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) that will contribute to the sound development of Zimbabwe with the promotion of Zimbabwean exports on the world market. Another large monetary supporter is China, who Zimbabwe has turned to for help in restoring its agricultural productivity. The recent entering of China into the WTO, has led them to begin to make large foreign direct investments throughout the world. The ties between China and Zimbabwe have been based upon Zimbabwe’s tobacco, which China buys in large quantities each year. China’s interest in the agriculture of Zimbabwe has led them to begin to make investments in the country. A Chinese state company, the China International Water and Electric Corporation, has been awarded a government contract to farm 250,000 hectares in southern Zimbabwe (Meldrum 2003). Chinese and Zimbabwean developers estimate that the project could yield 2.1 m tons of maize a year by producing three crops a year. This would easily satisfy Zimbabwe’s annual domestic demand for 1.8 m tons of maize. According to the Zimbabwe media, the Chinese deal was hailed as “a major breakthrough in Zimbabwe’s quest to return to food self-sufficiency” (Meldrum 2003). The government has not revealed how much it will pay China for the development of the huge agricultural scheme, which calls for the company to establish a costly irrigation system. However, it is believed that the payment will be made with tobacco, which China buys in large quantities from Zimbabwe each year (Meldrum 2003).

Conclusion

The key to this land reform program is that the rule of law be restored; not for the protection of existing commercial farming interests, but to ensure that redistribution of land is carried out fairly and to bring an end to state-sponsored violence and impunity for violent crime. Legal safeguards are necessary to ensure that land redistribution does not result in further discrimination and human rights abuses against those who are supposed to benefit from it. Once some sort of stability has been restored, and violence ended, the competing claims of commercial farmers, farm workers, new settlers, and the state to land must be arbitrated by an impartial tribunal with authority to resolve disputes over land and distribute the land fairly. The international community should halt their destructive policies and give generous assistance to efforts to ensure a sustainable settlement to the land question in Zimbabwe.

Endnotes

(2001). World Bank, World development report 200/2001: attacking poverty. New York ; Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1.

(2002). "FAST TRACK LAND REFORM IN ZIMBABWE." Human Rights Watch 14(1A): 45.

(2002). “Zimbabwe; Poll Result a Blow to UK’s Ambitions.” Africa News. 2003.

(2002). “Zimbabwe; Democratisation in Harare: Problems and Prospects.” Africa News. 2003.

(2002). “Zimbabwe’s tainted election: verdicts from around the world.” Agence France Presse. 2003.

Agriculture Ministry of Lands, and Rural Resettlement (2001). Land Reform and Resettlement Programme: Revised Phase II. Harare, Government of Zimbabwe.

Andrew Meldrum (2003). “Mugabe hires China to farm seized land.” The Guardian. www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,3604,894263,00.html. 2003.

Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (2002). Zimbabwe, country, Africa: Bibliography, Infoplease.com. 2003.

Fahim Ahmed (2002). Stop Imperalist Intervention in Zimbabwe. Global Analysis Zimbabwe.com. www.glob.co.zw/political/stop_imperalist_intervention_in.htm: 9.

iafrica.com Zimbabwe Geography, Deloitte and Touche. 2003.

Klaus Deninger, and Lyn Squire (1998). "New Ways of Looking at Old Issues: Inequality and Growth." Journal of Developmental Economics 57(2): 257-285.

Klaus Deninger, Francisco Lara, Miet Maertens, and Pedro Olinto (April 2000). Redistribution, Investment and Human Capital Accumulation: The case of Agrarian Reform in the Philippines. World Bank's Annual Conference on Developmental Economics, Washington DC.

N. Birdsall, and J.L. Londono (1997). "Asset Inequality Matters: An assessment of the World Bank's Approach to Poverty Reduction." AEA Papers and Proceedings 87(2): 32-37.

P. Aghion, Caroli, E., and Cecilia Garcia-Penalosa (1999). "Inequality and Economic Growth: The perspective of the New Growth Theories." Journal of Economic Literature 37: 1615-1660.

Pranab Bardhan (1997). "Role of governance in economic development: a political economy approach." Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: 94.

Robin Burgess (1998). "Land, Welfare and Effeciency in Rural China." London School of Economics(mimeo).

T. Burgess and R. Beasly (1998). "Land Reform, Poverty Reduction and Growth: Evidence From India." mimeo, London School of Economics.

United Nations Development Programme (2002). Zimbabwe: Land Reform and Resettlement: Assessment and Suggested Framework for Future- Interim Mission Report. New York, UNDP: p. 12.

World Bank Group (2001). Zimbabwe at a Glance, World Bank. 2003.

Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum (2001). Politically Motivated Violence in Zimbabwe, 200-2001: A report on the campaign of political repression conducted by the Zimbabwean Government under the guise of carrying out land reform. Harare, Political Violence Report January 2002: 4.

APPENDIX: Pictures Courtesy of “Your Dot Com for Africa” hosted by Marek. http://www.marekinc.com/PhotosZimChangesCourse.html

Figure 1: Tribal Trust Lands contain the majority of the unproductive and infertile land, and are specifically designated for the Africans for subsistence farming. The most fertile lands are possessed by the Europeans and designated as Commercial Land.

Figure 2: Comparison of Black vs White Farm

Wilson Katiyo and his father Tigere live on the families communal homestead at Makaha. The poverty and arid conditions are a drastic contrast to the prosperous white farmers, such as former government minister Geoffrey Ellman-Brown and his wife, Hilda. They own 35 acres outside Salisbury, a major city.

Figure 3: Food Shortages in 2002/2003

Highly insecure areas signify regions hit by drought and most severely effected by corn shortages due to underproduction of resettled farmlands. In 2002, 7.8 million people required food aide or they would starve.

Figure 4: Farm Workers Struggle

Some white-owned

farms have been originally slated to be handed over to the state as part of the

government's land redistribution program, but this is one of the few that has

been allowed to remain under its current ownership because of high productivity

at a time when Zimbabwe is facing a famine. However, once closed, they will be

without jobs. Farmers still working, or

those who did not want to loose their jobs have suffered attacks of violence

and aggression from their own people.

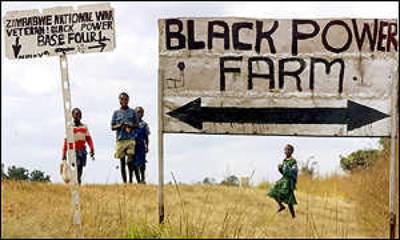

Figure 5: Land Occupations Accompanied by Violence

While some resettlement ran smoothly, other farms were taken over forcefully. This is an example of a farm now being guarded by the resettlers, who hang a flag of Zimbabwe with Mugabe’s face on it in support of the Fast Track Land Reform Policy.