Lab 7: Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B)

Overview

For the this lab we'll look at decoding packets from Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B). This is the system used to track aircraft in real time. Each plane constantly sends out a stream of digital packets. These are on-off keying, and are a great first project for decoding packet radio. There are many interesting aspects of how this system works.

If you want to get right to the lab, and your part, you can skip down to the “Decoding ADSB Packets” section below.

Introduction

ADS-B transmitters are currently carried by all planes in the US. Commercial aircraft use these packets to periodically broadcast their tail number, flight, altitude, direction, and speed. Light planes can transmit shorter packets that simply identify them. By 2020 all planes in US airspace were to have to their full information and status, but that is still continuing now. Other countries have sightly later schedules.

In the past planes were tracked with radar. This does a great job of detecting planes, and measuring their range and velocity towards the radar. It does less well for localizing the plane in angle space, due to the beam width, and has no idea which plane it is interrogating. The basic idea of ADSB is that planes have a very good idea of where they are from GPS, and who they are, and where they are going. All the air traffic control system needs to do is ask, and the plane will be able provide all this and more.

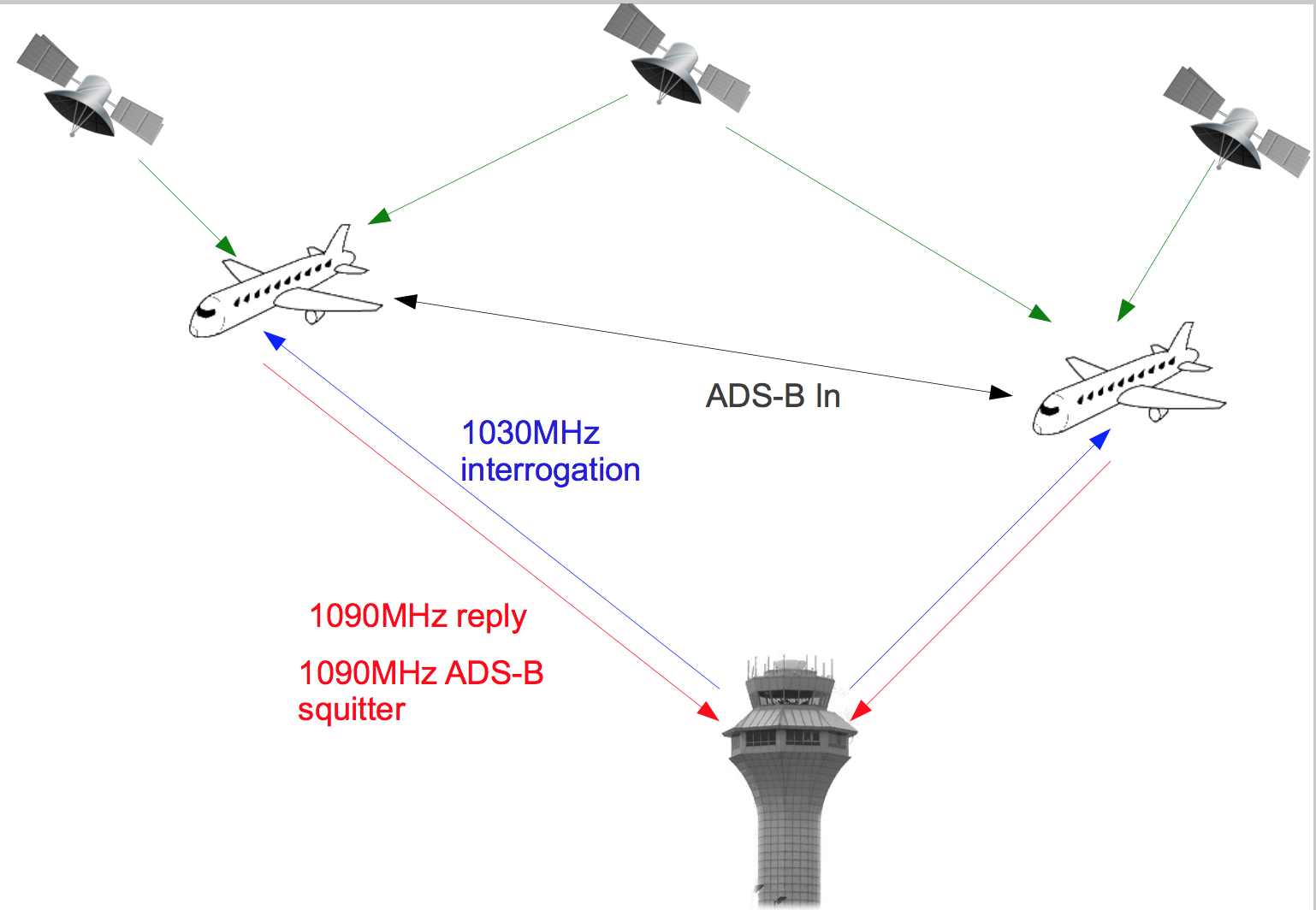

The general layout of the system looks like this:

The planes listen to the GPS system to figure out where they are, and then transmit that information to other planes and ground control using short digital packets.

The packets that are sent are called “squitters”, a term which originated in the military with Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) systems. The goal of this lab is to acquire and decode these packets.

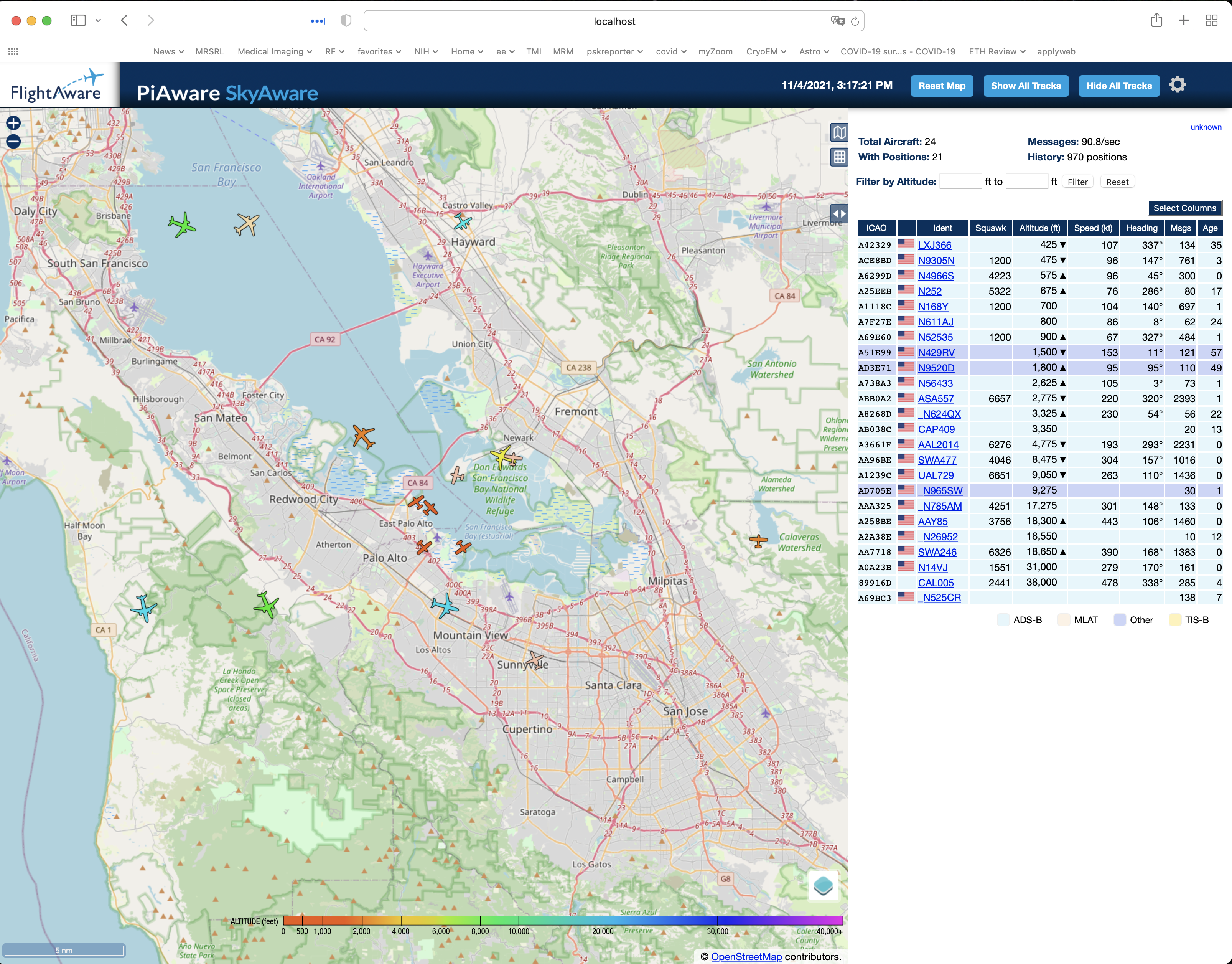

Programs like dump1090 on macos and linux (and many more on Windows) use your rtl-sdr to acquire and track the ADSB packets. An example from yesterday afternoon is shown below,

This is in the afternoon about 3:30. You can clearly see how the planes are lining up for SFO, and lots of small plane traffic around San Carlos. The small planes have only recently started appearing in large numbers. If you click on a plane, it gives you its flight information including it current flight track.

Since ADSB is public, many web sites aggregate the ADSB data from a wide range of sites to provide real time information about where flights are, and the flight paths they have taken. Two are Flightaware.com and Flightradar24.com. This is very useful.

An example from Flightaware for a flight a few summers ago is

These sites actively recruit people with rtl-sdr's to participate in their network, and even sell branded rtl-sdr's explicitly for this purpose:

The hardware is free if you are in an area that needs coverage (sorry, the Bay Area is already pretty well saturated!).

The most important fact about ADSB is that it is not encrypted. This makes the location and identity of every plane public information. This is significant. Numerous law enforcement agencies use surveilience planes or helicopters, and these all have tail numbers, and transmit on ADSB. All of these activities are now publicly available. Google FBI and ADSB, or CIA and ADSB for example. You will find lots of interesting things.

Another interesting example is following the location of Vladamir Putin. When he flies, his aircraft transmits on ADSB, and you can track his trajectory. One plane he often uses has a tail number RA-96012. If you type this in to flightradar24.com, it will show you where he has flown in the last week. Pay for a subscription, and you can follow his flight for the last couple of years. It is pretty interesting which airspace he flies through, and which airspace he avoids!

Another interesting example is Putin's doomsday aircraft. This is a telecommunications aircraft that circles above his location wherever he is, to make sure that if buttons need pressing, they will work. There are a couple of these, but one example is here

For the U.S., Air Force 1 generally turns off its ADSB transponder, but occasionally does turn it on.

Decoding ADSB Packets

Before starting to acquire signals, it is useful to check to make sure there is something out there! If we run gqrx and look for packets at 1090 MHz, we see something like this:

This should a little like the packets you captured for this week. Packets are very short, so they spread across the spectrum. Each time a packet comes in, the spectrum jumps. There is a lot of traffic! We are going to collect some of this, and decode it.

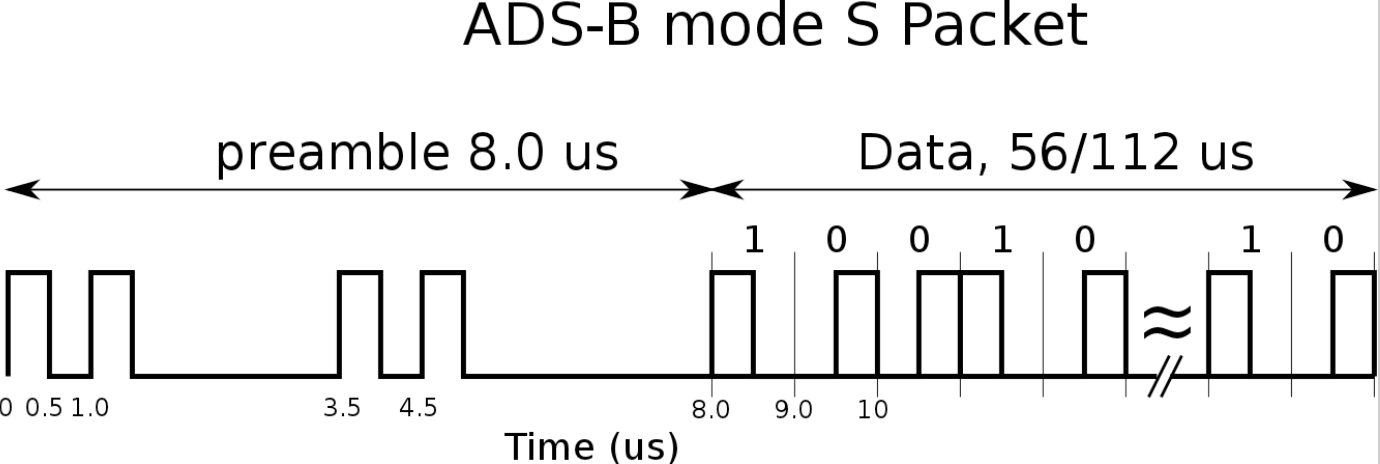

The ADSB packets are short sequences of pulses, that look like this:

Each pulse is 1 us long, and consists of two 0.5 us pulses. There is an 8 us preamble that allows you to find the start of the packet. It's spacing is unique, and can't turn up in a packet. The packet itself follows, and is either 56 or 112 us long, which decodes to 56 or 112 bits. Bit are encoded as a split phase pulses, where a falling transition is a 1, and a rising transition is a 0.

The split phase pulses are exactly at the Nyquist limit if we sample at 2 MHz, as we have been doing in the previous labs, and that will make resolving the pulses difficult (although that is what is commonly done!). Fortunately the rtl-sdr's that you are using will sample up to 3.2 MHz, which is fast enough that we can see the pulses clearly.

Capture some data with

> rtl_sdr -f 1090000000 -n 16000000 -s 3200000 adsb_32.dat

This will give you 5 seconds of data. Here is a capture I did

Load them into matlab

>> da = abs(loadFile('adsb_3.2M.dat'));

There was an earlier file adsb_32.dat which is not quite as active. We'll give you an even better file below, with lots of activity.

We are only concerned with the envelope, so we use the absolute value. The bit boundaries are on 1 us increments, which doesn't match our 3.2 MHz sampling rate. We'll upsample to 4 MHz to make make the bit boundaries line up with the samples

>> d = resample(da,5,4);

This upsamples by a factor of 5, then downsamples by a factor of 4 to leave us at (3.2 MHz) * 5 / 4 = 4 MHz.

If we plot the first 1e6 samples, we see something like this

Each of the spikes is a packet. Use your matlab zoom to visualize one of them. One packet is shown here

You can clearly see the preamble and the data bits. If we'd only sampled at 2 MHz, the result would have been

which is much harder to decode!

If we take the 4 MHz sampled data and threshold it we get the ADSB waveform

Then subsampling by a factor of 2 and shifting to the first non-zero bit, we get the ADSB bit stream for the packet.

We decode this as

Since the packets are only 56 or 112 bits, a lot of effort has been devoted to compressing as much information into the packets as possible. This is fairly intricate. We'll restrict our attention to finding packets with the fight numbers of the planes. Each plane sends these out every 2 s.

The bits in the 112 us ADSB packet are allocated as follows,

The first 5 bits after the preamble identify the type of packet. This will be 17 or 18 for planes communicating to the ground. We are only interested in the DF 17 packets. The next three bits tell something about where the plane is, we'll skip these.

The unique identifier for the plane is the next 24 bits. If you format these bits as a hexidecimal string, and type that into google, you will find out which specific airframe this is, who owns it, and what they do with it.

After that is the data bits, that we will decode. This looks like

The data field can be decoded for the flight number like this

The identify packets we are looking for have an initial 5 bits (bits 33-37) of [0 0 1 0 0], like the packet above. This is the TC field. Search for this to decide which packets to decode. There are lots of other DF 17 packets that report altitude, direction, and location. Only a few of the DF 17 packets are identify packets. These are sent out every 2 s, while each of the others is sent out every 0.2 s.

After the initial 8 bits of the data packet, the characters for the flight number are sent as six bit integers, where each integer encodes for a character

#ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ#####_###############0123456789######

The # entries are not used. This can be summarized as 1-26 => A-Z, 48-57=> 0-9, and 32 => space. In matlab, you can implement the decoder as

function decode_id(pd)

% decoding vector

dcd = '#ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ#####_###############0123456789######';

% number of packets, np, and the packet length lp

[np lp] = size(pd);

% for each packet

for jj=1:np,

cs = [];

% decode 7 characters 6 bits at a time

for kk=1:6:(6*7),

% compute the value of the next 6 bits

nc = sum(pd(jj,kk+[40:45]).*(2.^[5:-1:0]));

% look up the value for this 6 bits in the decode table

cs = [cs dcd(nc+1)];

end

% display the result

disp(cs)

end

where pd is a matlab array of row vectors of 1's and 0's for each packet.

There is only one identify packet in the capture given above. To test your decoder, here are a couple of other identify packets to work with

pd = ['8da6e45a213b5d3340482042cea1' '8da6c8262214a075cf68204fa2ea' '8da5861e223b4d754538202b41ee' '8fa9ee47213b7cf954c820d0b829' '8da03f4825184633c75ce0c25fd9' '8da2e62120592131df1d609c4876' '8da0a457234cb5f5d39e2071ffa5']

These are in hexidecimal. To convert them into an array of bits for the decoder above, use this

function b = hex2bin(s)

bta = [0 0 0 0; 0 0 0 1; 0 0 1 0; 0 0 1 1;

0 1 0 0; 0 1 0 1; 0 1 1 0; 0 1 1 1;

1 0 0 0; 1 0 0 1; 1 0 1 0; 1 0 1 1;

1 1 0 0; 1 1 0 1; 1 1 1 0; 1 1 1 1];

b = [];

for jj=1:length(s),

kk = sscanf(s(jj),'%x');

b = [b bta(kk+1,:)];

end

end

A couple of flight numbers you should find are N543PD , FDX3153,and SKW5498.

Lab Report

For your lab report, try your processing code on this data set

This was acquired during a much busier time of the day. There are about 400 packets of various types, with at least 7 identify packets (not bad for 2 s of data!). The optimum threshold varies by packet, so you will get different planes with different thresholds. Try threshold levels of 20, 10 and 5. A better approach would be a packet level specific threshold, but that is beyond this lab.

Decode the 24 bit ICAO identifiers as hex integers. Report how many unique planes to you hear. There will be lots of these packets because it includes all of the commercial planes, as well as light aircraft that don't have full adsb transmitters. I get 11 unique ICAO numbers with a threshold of 20.

Only some of the packets are the identify packets we are looking for. These have the first five bits after the preamble (bits 1-5) of 17, and a TC field (bits 33-37) of [0 0 1 0 0]. The data packet then encodes the flight number. Decode these using the mapping given above. You can type them into google, and you can see where they are coming from and going to, but that is not required for this lab.

Include your m-files for each of these functions in your report.

Just for Fun

Real Time ADSB Plane PLotting

Use your rtl-sdr to acquire ADSB data, decode it, and map it in real time. Thats where the plots above came from. Set your antenna up with an appropriate length, and vertical polarization. For Windows users the most popular program seems to be Plane Plotter. This comes as a self extracting .exe file. It has a free 21 day trial period, after which it costs 25 Euros. For the Mac and Linux, the key piece of software is Dump1090. This captures and decodes the data. The actual display is usually handled by other programs (typically a web server and a browser). Some basic installation guidelines for the mac are here. Raspbian even has dump1090 in its package manager. 1090 MHz doesn't go through buildings too well, so put your antenna in a window, or go outside. If you can see the planes, you can pick up their signal.

Dictator Alert

Check out Dictator Alert for a crowd sourced approach to track “authoritarian regimes.”

Unfiltered ADSB

Most of the flight data aggregators filter out planes that the government would rather not have tracked, such as military, police, and other agencies. However, the packets are broadcast in the clear, and anyone can receive and decode them. One site that aggregates all available data is ADSBExchange. Here is what the Bay Area looks like yesterday evening

There are 64 planes visible. I clicked on an unusually shaped one, and it turned out to be a C17 just landing at Travis Airforce Base. There are also a Contra Costa County helicopter looking for something

See what you can find!