Case Study:

SVB IN CHINA

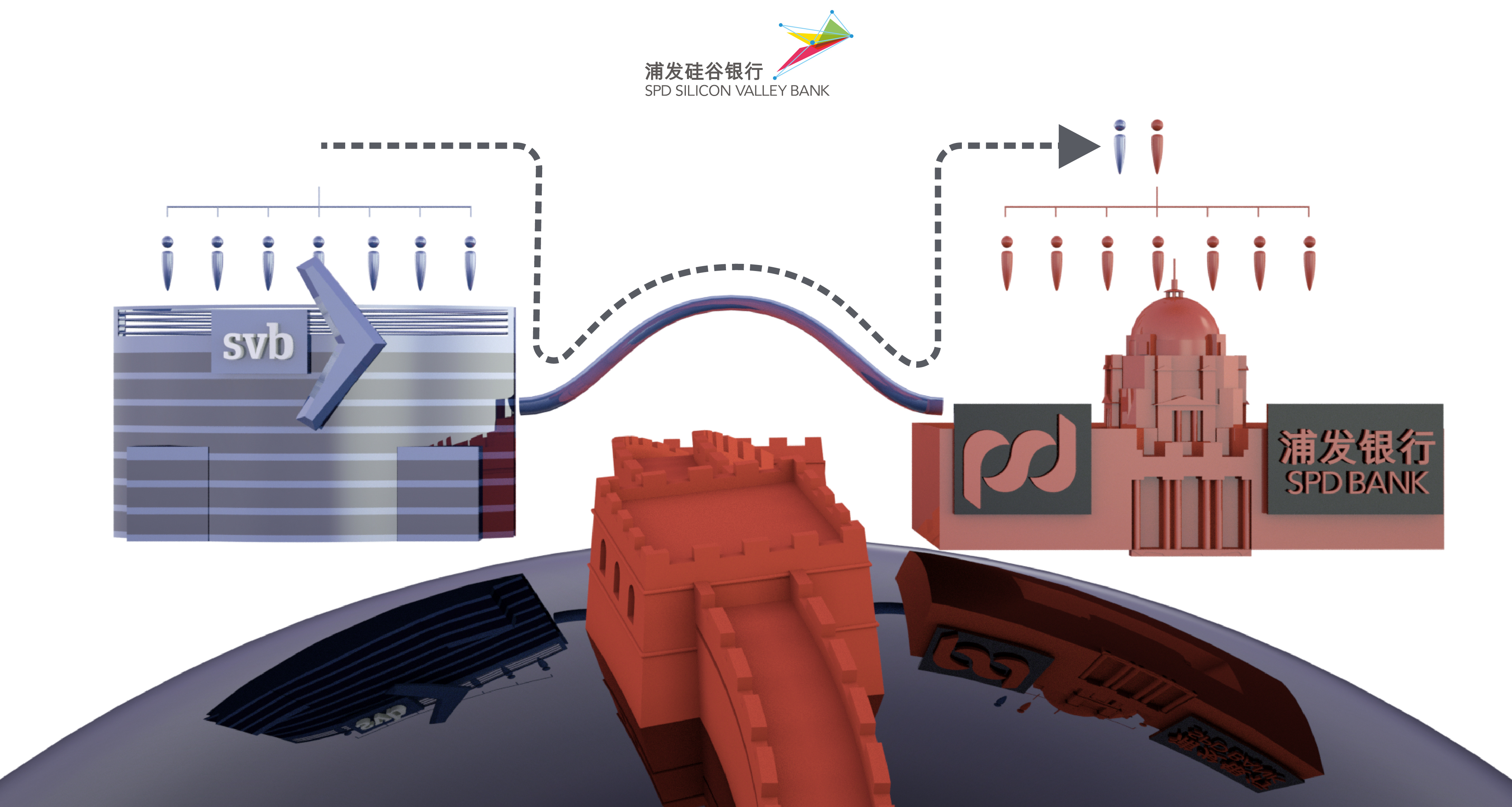

SVB IN CHINA

| “ | Wall Street was beating on us. They wanted a significant layoff. We said significant layoffs are a bad idea because they destroy culture. On top of that, it takes 10 years to train a banker. We’d lay these people off and want them back again, but instead they’d be working for competitors—really a bad idea. And while this strategy got off to a rough start, things eventually turned.2 | ” |

| “ | Long term, I believed that technology was the only niche that wasn’t adequately addressed by other banks. Every other niche was banked by hundreds of competitors. But most banks still thought of technology as risky, especially in 2001. I saw an industry with lots of good characteristics where we had a distinct advantage and little competition. So I decided to really focus on technology. Over the next four years, I wanted to get our portfolio to 95 percent technology companies. Given what had just happened with the dot-com bubble, this was a controversial approach. But it was something I believed in strongly. | ” |

| “ | We’re on the top floor of the Park Hyatt Shanghai, the tallest hotel in the world. It’s the end of the week, and we had every board member summarize a couple points. What were their impressions? What did they think? Are we being too aggressive going into China? Are we not aggressive enough? What’s their point of view? It was a really open discussion, and really interesting insights. And at the end it was the conclusion by almost everyone—we really don’t have a choice but to do this. And we have to be committed to it. We have to think about it long term, and we have to have the right people involved. I said to the board: “Let’s look at it. We’re going to put $80 million into this thing, right? We have to be comfortable that we can write off that $80 million. And if you’re not comfortable—if people around this table aren’t willing to say that’s acceptable—then we should stop now and do something different because it could happen." | ” |

| “ | The reaction I had was holy crap, there’s a huge opportunity here—and a lot of work to get done—and a lot of things we’ve never done before at SVB. So it was a reaction of opportunity and a reaction that took my breath away. In fact, it took the entire executive team’s breath away. | ” |

| “ | We wanted people that had a high level of competency and business savvy—the best of the SVB employees. But in addition, they had to be professionals who could pick up their families and move. But even more than that, we had to find people who had the aptitude for challenge—those who wouldn’t be thrown when things didn’t necessarily work out as easily as perhaps they’d like, and those that could assimilate to a new culture. | ” |

| “ | The government approved the joint venture in October 2011. Shortly thereafter, we had five people ready to go—the 50 percent of senior management representing SVB. But then we waited four months before we heard who would join from the SPDB side. At first, I was upset at SPDB’s CEO for taking so long, until I realized the CEO can’t hire top employees. Instead, they need to be appointed by SPDB’s party committee of 8 to 10 people, which takes a long time. | ” |

| “ | Ken brings to the table an extraordinary perspective around culture. His dad was an industrial psychologist, so he was used to talking about various cultures around the dinner table. That burned its way into Ken’s DNA, and he brought that view to his work as global CEO, and then in running China. Initially SPDB employees were somewhat reticent to get on board—they didn’t really want to join the joint venture. However, over time they heard about this guy named Ken Wilcox, and this culture he was creating, in a much smaller pool than what they were used to playing in. So, their sense of contribution and their sense of affirmation was much more profound than they had been used to at SPDB. The success of SSVB would not exist if it weren’t for Ken and his ability to leverage culture for better outcomes. | ” |

| “ | One of the attorneys appointed to be a part of the team displayed a really bad attitude toward the joint venture and towards the American participants. We knew he would be a risk to our success, and we knew we had to remove him from the team. But getting rid of him was much harder than we thought because all appointments are made by the party committee, which is the representation of the Chinese Communist Party. We eventually succeeded, but it wasn’t easy. | ” |

| “ | Our clients were indigenous Chinese technology companies who almost exclusively used renminbi. Whether paying employees or purchasing from vendors, they needed renminbi, not U.S. dollars. Even if they purchased from a foreign vendor, they had to use a Chinese trading company as an intermediary, and the trading company accepted renminbi. It was crucial for us to conduct business in renminbi if we wanted to grow our client base, and I spent several years lobbying to make this happen. | ” |

| “ | Our vision is to be the most sought after financial partner for entrepreneurs, innovators, and enterprises in the innovation space. We want them to come to us because we offer so much value to them. We want to make the right introductions to corporate partners and scale up with them. If a company in China wants to expand to the U.S., we want them to think of us. If a U.S. company wants to expand to China, or Europe, or anywhere, we want them to think of us. You go back the last couple years, and we’ve added $25-$30 billion of assets to manage—that growth has really been unparalleled, on a percentage basis, by any bank in the United States. As part of a global innovation economy, we think we can continue this growth for the foreseeable future. | ” |

Ryan Kissick (MBA 2014) prepared this case as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation, under the supervision of Hayagreeva Rao, Atholl McBean Professor of Organizational Behavior and Human Resources, Graduate School of Business, and Robert Sutton, Professor of Engineering, School of Engineering, Stanford University.

Ryan Kissick (MBA 2014) prepared this case as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation, under the supervision of Hayagreeva Rao, Atholl McBean Professor of Organizational Behavior and Human Resources, Graduate School of Business, and Robert Sutton, Professor of Engineering, School of Engineering, Stanford University.