Equity’s transformation into a rapidly growing retail bank was widely considered to be an

inspirational success story. One industry analyst voiced a popular opinion that “by providing

banking services to the masses and generally expanding its distribution channels and services,

Equity Bank will be a star performer.”

11

In 2006, EB served more than 1 million customers -

over 31 percent of all Kenyan bank accounts. The company’s official mission was “to be the

preferred microfinance service provider contributing to the economic prosperity of Africa.”

While resoundingly for-profit, Equity also retained a passionate commitment to empowering

Kenya’s poor to improve their livelihoods and prospects for self-sufficiency. Industry experts

routinely cited EB as the “best bank in retail banking”

12 due to, among other factors, their

customer dedication and talented management team. In addition to enjoying widespread

recognition domestically, the company began to attract international attention, as other

developing countries in Africa and Asia sought to learn from Equity’s low-margin, high-volume

model.

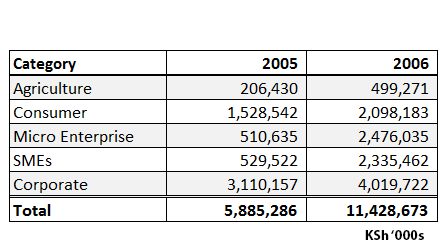

Equity Bank offered both deposit and loan products designed specifically for their target market.

Equity’s deposit products included accounts for personal, business, church and institutional

savings, current accounts, call and fixed deposits and a product called

Jijenge13 that helped

customers model out and stick to savings plans for specific goals (e.g. a new car).

The deposit products themselves were fairly commoditized within the retail banking industry.

What set Equity apart from the competition was how the access to and pricing of those standard

offerings was tailored to the previously “unbanked” segment of the market. While multi-national

institutions required proof of property ownership or other forms of conventional collateral,

nothing more than a National ID (a document every citizen had) was needed to sign up for an

account at Equity Bank.

14 Minimum balance requirements were waived entirely, as were

“account maintenance” fees. Service charges on withdrawals at Equity were about KSh 50, or

just 10 percent of what the incumbents typically charged. By dropping prices substantially,

Equity Bank addressed the financial discomfort its target customer felt from absorbing regular

fees on savings and services. Henry Karugu, marketing and product development director,

explained, “Banks here levy charges in many ways. So, the perception is that your money might

be safe because it’s in a bank…but it’s not secure from the institution itself.”

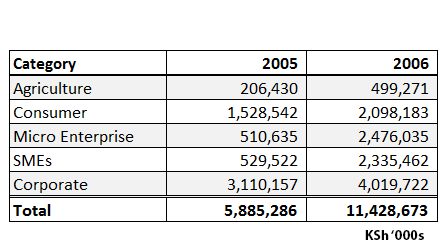

In 2006, Equity paid an interest rate of 1.25 percent to account holders on deposited funds. In

order to cover the interest expense and earn a profit, the bank created four types of loan products

with an average lending rate of 17.5 percent:

Social – for medical, household, education and emergency loans

Working Nation – for salary advances and larger “check off” loans

Agricultural – for farm development, animal feed, vet services and livestock

Private sector – for micro-enterprise, overdraft, working capital and business growth

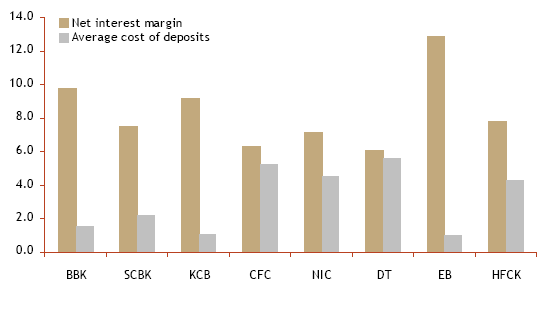

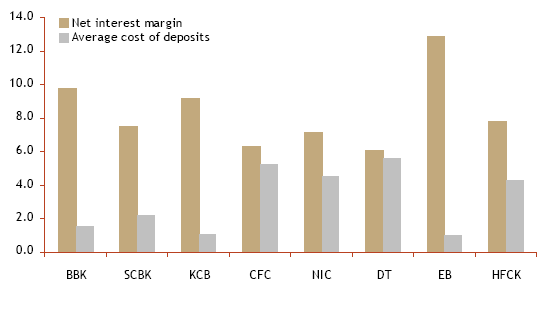

EB’s lending rate was high compared to the sector’s average of 13.7 percent because of the

profile of its borrowers and the focus on microcredit. Equity made loans

available to all account holders once they had been deposit customers for at least six months.

Both the size of the loan and its repayment schedule were customized to each applicant by

specially trained branch credit officers. In 2006, EB loans ran from KSh 500 to over KSh 50

million depending on each applicant’s ability to repay.

Rather than apply the conventional banking wisdom that pre-existing property was necessary to

back credit outlays, EB management and employees committed to finding “flexible” sources of

collateral to back loans. For example, salary advances were secured directly with one’s

employer through an automatic paycheck transfer. For self-employed entrepreneurs, personal

belongings, including marriage beds, were sufficient to qualify. This approach helped open the

market to creditworthy candidates who had previously been considered “unbankable.” As Alex

Muhia, general manager and personal assistant to the CEO, stated, “The majority of Kenyans

will not be able to give you a title deed or car log book. Especially women - they can’t offer you

anything. But when it comes to loan repayment…women are the best.”

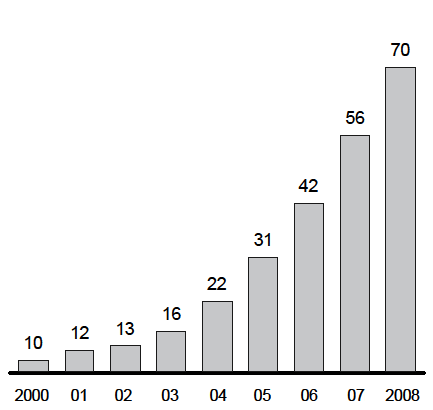

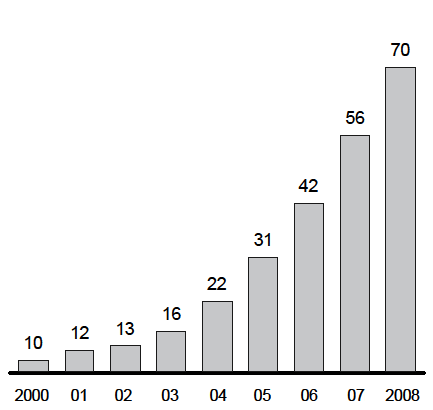

Since 2002, Equity Bank managers pushed to scale as quickly as possible. The number of

branches expanded from 13 in 2002 to 42 in 2006, with 70 anticipated by 2008.

This was a significant roll out, given that Barclays Bank of Kenya (Barclays), the largest

financial institution in the country, only had 58 branches in 2006.

Equity had three types of branches: “regular” for their core individual and small business clients;

“mobile” for rural customers living in areas for which a permanent location was not yet

economically viable; and “prestige” for Equity’s emerging affluent segment who had grown with

the bank over time.

The typical branch had two floors, each one dedicated to a specific type of customer. The

bottom was reserved for individual customers, while the top was designed for corporate clients.

Equity split its clientele to offer more privacy to business customers, who tended to make larger

cash transactions. All visitors chose from four main destinations (available on both floors):

Tellers − primarily managed balance questions, withdrawals and deposits.

Credit Officers − assessed credit-worthiness, offered loans and closely monitored the

quality and size of their portfolios.

Customer Service − answered questions, addressed and monitored complaints.

Account Openings − processed National IDs and other information to set up each

deposit account holder.

Customers could also visit the branch manager without an appointment, an unusual level of

accessibility in Kenya.

15

Equity had an average of 24,238 customers per branch in 2006, which was very high relative to

the industry average of 6,383 clients per location. Due to the volume of accounts, Equity

branches often had cramped lines of at least 35 customers snaking through the building. As a

result of increasing customer complaints, the bank installed over 120 ATM machines throughout

the country, more than any other bank, to enable automatic withdrawal and deposit. By mid-

2006, ATMs accounted for over 40 percent of withdrawals. In order to further decongest the

banking halls, Equity then introduced two additional alternative banking methods; Internet and

mobile phone banking. Both offered the ability to check balances and transfer funds between

accounts, among other services. Customer uptake of these locally unconventional methods was

slow to moderate, and most permanent locations continued to have a significant amount of foot

traffic. To further reduce considerable crowding, bank managers also began exploring point of

sale banking (e.g. drawing cash at the supermarket check-out).

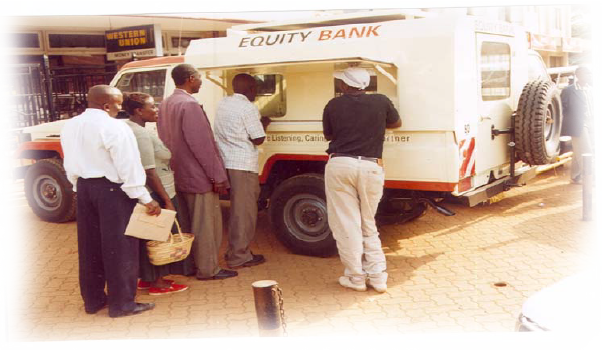

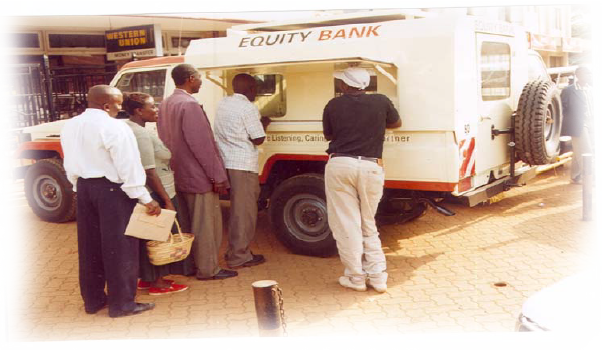

EB outfitted branded, armored trucks to serve as mobile branches in rural locations that did not

yet have enough foot traffic to support a permanent location. A mobile branch

manager and staff would drive in the banking van to one of five sites each week, returning to the

same “home” branch each evening. A pared down set of deposits and loans were offered and the

mobile branch manager used a lean version of Equity’s IT system to process transactions. EB

expanded security for these automobiles (when car jackings became more frequent in the early

2000s) by assigning an armed guard and chaser cars to each.

Equity’s drive to empower some of the country’s poorest citizens resulted in the emergence of a

customer segment that became relatively wealthy over time. These clients began to approach the

level of personal net worth at which the multinational banks became interested in “banking”

them. In order to stave off the competition, and better serve customer needs, Equity created two

“prestige” branches. These locations offered largely the same products as regular branches, but

customers had to maintain a minimum balance of KSh 50,000 to be eligible. As a result, the

banking halls had a very different feel - quiet and spacious, well-appointed with comfortable

seating where visitors could watch TV, refreshments were provided, and the surroundings looked

new and well-maintained. EB staffed these branches with bank employees who had

demonstrated impeccable customer service skills over several years in regular branches.

Security was a top priority at every Equity location. The bank put a number of measures in place

to prevent robberies and other disruptions. Armed guards were stationed in every branch. They

also played a secondary role of directing foot traffic inside the banking halls. All vaults were

protected by a series of electronically-operated doors and gates. Enterprise and prestige clients

had their own dedicated cashiers who worked in separate cubicles with lockable doors. Equity

officials also stayed closely connected with local police and other banks in order to stay

informed about recent crimes and suspects.

Until Equity installed Banker’s Realm (BR), its first core banking software, in 2000, all banking

services had been manually processed. By 2004, BR began to show signs of stress like

“hanging” due to the bank’s dramatic customer growth. In addition, it could not handle the

introduction of ATMs. Banker’s Realm consultants were almost permanently stationed at the

bank’s headquarters to manage capacity issues and hold the system together.

After customer and branch complaints increased, Equity began a concerted search for a new IT

system. Peter Gachau, head of IT, noted, “We did not care if it cost KSh 67 or KSh 670 million,

we were just determined to get the best possible solution.” Eventually, Gachau and his team

invested KSh 650 million into a three-part system that had plenty of room to scale as Equity

grew. It consisted of:

An Infosys core banking system called “Finacle”

An Oracle database

An HP hardware platform

The Finacle system covered daily bank processes and products for consumer banking, including:

savings and checking, deposits and consumer lending as well as those required for corporate

banking and trade finance. It linked the branches, ATMs and mobile banking channels back to

the centralized head office for data collection and management. Prior to rolling out the solution,

the company invested an additional KSh 17 million into training the entire organization on how

to use it.

Once installed and refined, the IT system produced nearly immediate results. Account openings

and cash transactions went from requiring 25-30 minutes to 5-10 minutes, which meant that

customers spent less time standing in line.

16 Transaction (e.g., phone, postage) and branch

expenses both dropped,

17 fast data centralization enabled faster account reconciliation and Equity

Bank was able to respond more nimbly to demand for innovative products.

18 In addition, Finacle

seamlessly interconnected EB’s other specialized software solutions, including MEEPS,

19

SWIFT, RTGS and the “lean” version of Finacle used in Equity’s mobile branches.

Equity used a high-touch approach to acquire account-holders and retained them by offering

exemplary customer service. EB’s retail customers were primarily small-scale farmers (e.g.,

dairy, rice and tea), entrepreneurs and low-end salaried workers. These

“average” Kenyans, roughly 80 percent of the country’s population, often lived below the

poverty line as defined by Western standards. The firm’s positioning statement summed up the

brand attributes it used to appeal to this formerly unbankable population: “Equity Bank provides

accessible, customer-focused banking services for microfinance clients to meet their aspirations

for today and tomorrow. Unlike other financial institutions, Equity is down-to-earth and

friendly.” EB also espoused twin mottos of “the listening, caring financial partner,” and,

“growing together in trust.”

As signified by their motto, a key component of EB’s customer acquisition strategy revolved

around cultivating mutual trust with target customers. Since the industry downturn of the mid-

1990s, this market segment had been wary of re-joining formal banks. The large, multi-national

institutions that preceded Equity had created a damaging halo effect when they pulled branches

out of the less profitable rural areas with only cursory notice to customers. Not only was it of

practical concern that these communities no longer had a safe place to secure their savings and

acquire credit but, as Winnie Kathurima, change and corporate affairs director, noted, it also

“hurt the self-esteem of many people to receive letters that said ‘sorry, you’re not our customer

any more.’”

Equity endeavored to fill the vacuum by being market-led. As Kathurima mentioned, “We go

out and listen to the people. We say ‘What do you need? If you had a bank, what would you do?

If you were to borrow, what would you borrow for?’ And then we come back and develop

products that suit those needs.”

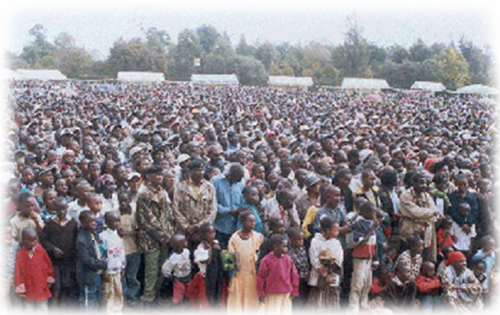

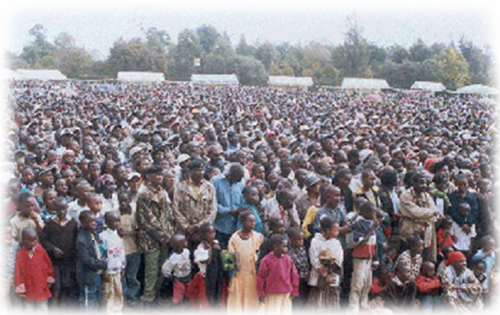

Equity began sending employees into rural areas to educate

potential clients about its offerings. In order to best reach locals, EB representatives set up

booths in open air markets, hosted free mass public “financial training and education days”

and established a presence at community agricultural trade fairs.

20 They also

conducted focus groups discussions and surveys.

Once newcomers decided to visit a branch, the marketing effort continued. All branch

employees were trained to promote the products and services best suited to each customer.

Credit officers received additional, specialized training on how to market particular loans. In

addition, the branches showcased posters and fliers that further described EB’s products and

services. To a lesser extent, the bank also funded radio spots in local dialects and

signage on lampposts in socio-economically depressed areas.

21

In describing core aspects of Equity’s brand, including modesty, accessibility and passion for

customer service, Mwangi recalled a story, now embedded within the bank’s lore, of an 80-year-old

account-holder who traveled 450 kilometers by bus to meet with him. The elderly man had

come unannounced, and after waiting hours to see the CEO, he said:

| “ |

When your bank opened a mobile branch in my area, me and my wife, we opened

our first savings account. And after some time we went and borrowed 10,000

shillings, and we bought a heifer which was almost ready to calve. And after

some time the heifer calved and now my wife, like other women, is able to take

milk to the factories. And today we don’t have to rely on my children, and we are

able to meet our expenses. Three years ago, we struggled. Now we have bought

a piece of land where we reside and we are fine.

|

” |

Mwangi asserted that Kenya’s low-income population derived much more than financial services

from having a bank specifically tailored to them. He noted:

| “ |

We bend over backwards for our customers. And the bank’s accessibility gives

them a strong sense of fellowship. Our customers say, ‘We have forever been

excluded, but now there’s a bank able to accommodate us - this is where I

belong.’ And that feeling of community and partnership gives them a very strong

sense of pride and self-esteem.

|

” |

Equity linked those positive feelings to the bank’s high levels of customer advocacy - over 50

percent of new customers were convinced to join by another account holder.

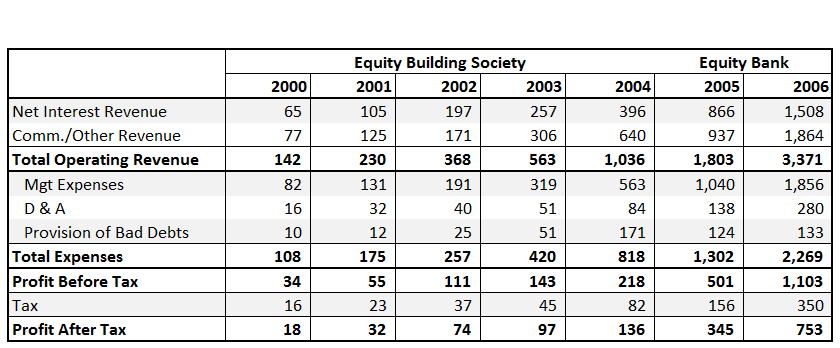

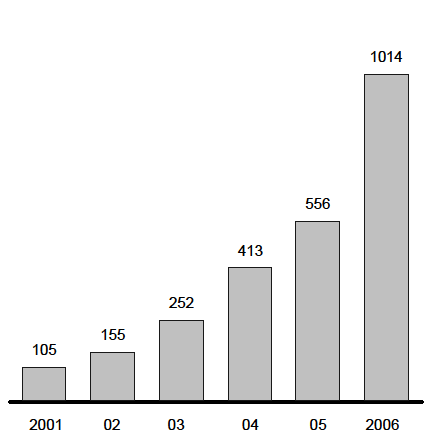

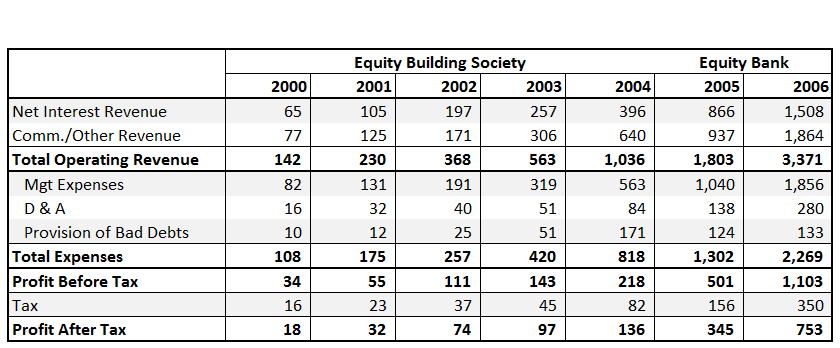

After Mwangi took over as CEO in 2004, the number of deposit clients more than doubled

within two years. Revenue increased by over 300 percent during that timeframe,

from KSh 1,035 million to KSh 3,371 million and pretax income more than quintupled, from

KSh 218 million to KSh 1,103 million. In addition, the pretax margin rose from 21 percent to 33

percent due to effective control of personnel and bad debt provisioning spend.

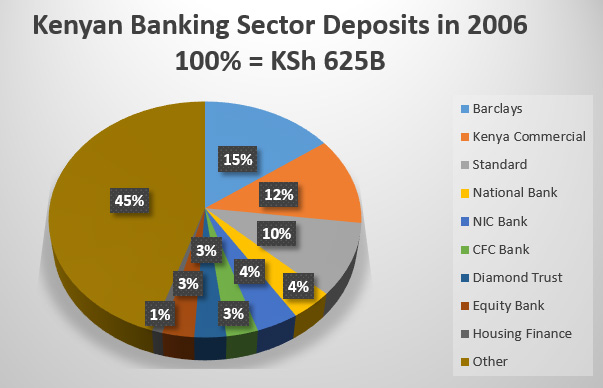

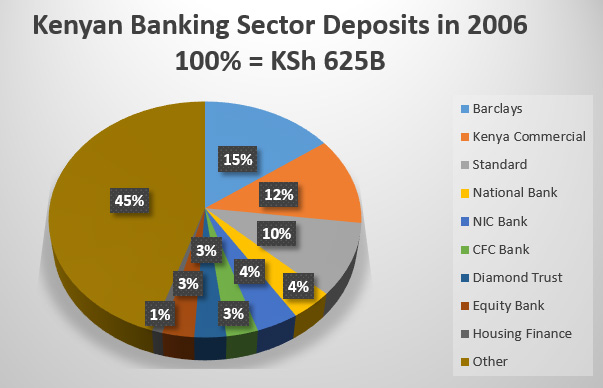

In 2006, Equity was the seventh largest bank out of 45 operating in Kenya based on profit, yet it

only had 3 percent market share of loans and deposits. Due to the relatively

limited means of EB customers, the average deposit account held just 10 percent of the value in a

typical customer’s account at larger banks including Barclays and Kenya Commercial. Yet, the

bank gained 14 percent of new deposits in 2006. Although some industry commentators feared

an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs) as the EB’s asset base increased, the quality of the

loan book as represented by the ratio of non-performing loans and advances to gross loans and

advances actually improved markedly from 10 percent in 2005 to 5 percent in 2006.

22

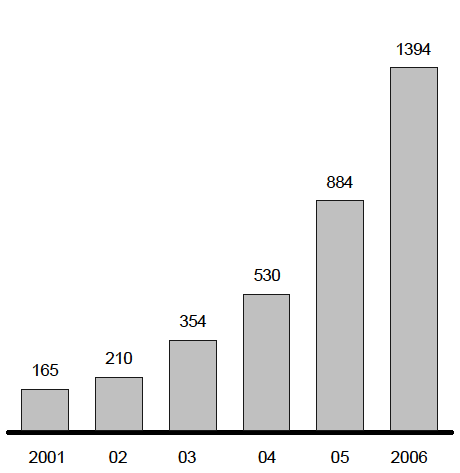

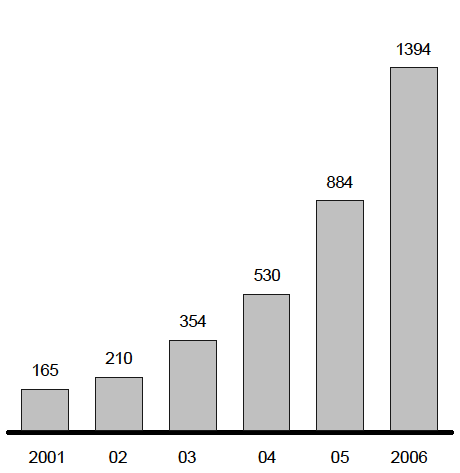

In an effort to drive sales, the number of staff expanded from 117 in 2000 to 1,394 in 2006, with

the biggest increases in the last two years. Yet, although annual management

expenses increased by 85 percent from 2004 to 2005 and by 78 percent from 2005 to 2006, this

line item stayed relatively constant as a percentage of net revenue. Helped by EB’s

comparatively attractive spread between lending and savings rates, Equity’s profit before tax

increased even faster than sales during this six year time period, from KSh 33.6 million in 2000

to KSh 1.1 billion in 2006.

Equity’s operating margin was 22 percent in 2006, somewhat below the larger players such as

Barclays and Standard Chartered, but also comfortably above other medium-sized players,

including the Cooperative Bank of Kenya. In general, Equity exercised fiscal discipline, for

example by breaking even on new branches within 6 to 9 months.

23

James Mwangi replicated the openness of the branches within the inner workings of the bank

itself. He and his executive managers maintained open door policies, even as the organization

stretched beyond 1,000 employees. As Equity evolved from a family-run to a professionally

managed institution, the bank began to explicitly celebrate meritocracy. The top 10 percent of

performers were placed on rotational programs to help them develop as future bank leaders.

Highly experienced executives were recruited from a range of competitive banks and other

multinational institutions. Every employee was placed on a six-month probation so that cultural

“fit” could be assessed in real time. Individuals who did not actively uphold the company’s

values were soon counseled out.

Employees at every level, both at the corporate office and within the branches, shared a firm

commitment to customer service. Equity’s secondary role as an indigenous community-building

organization (versus a large multinational) gave employees a sense of purpose and passion for

their careers. As Alex Muhia noted, “The majority of employees see what we do as a calling.

It’s not about the money … we believe in changing the destiny of normal Kenyans in a positive

and non-exploitative manner.” Nonetheless, as the bank evolved, HR managers ensured that

salaries and benefits were in line with the rest of the industry. Medical care and pensions were

part of most compensation packages and an employee share ownership program (ESOP) was

also offered. Staff also received extensive training. Equity managers expected that these

activities would directly benefit their clients. Peter Lengewa, head of human resources and

organizational development observed, “Investing in our employees is a prerequisite to exceeding

our customers’ expectations.”

James Mwangi expected that EB would have to face two main challenges in the future: increased

competition and threats to EB’s unique culture.

By 2006, Equity Bank’s fast growth and successful financial performance attracted the attention

of other players in the market. In addition to the larger MFIs, Equity also had to compete with

international financial behemoths including Barclays and national players including Kenya

Commercial Bank (KCB) and the Cooperative Bank of Kenya (Co-op). These banks all signaled

an intention to begin targeting poor Kenyans. Mwangi noted that increasing competition could

potentially result in a price war or higher marketing spend - both of which would depress

Equity’s margins. EB could even be a hostile takeover target, should one of these enterprises

attempt to “buy” their way into the sector, as opposed to building out the infrastructure to

accomplish it in-house. Finally, in what had become a tight labor market, Barclays, KCB and

Co-op had all made overtures to some of EB’s carefully trained staff - highlighting that it could

become more difficult to hold on to star performers.

A second key threat was the ability to stay client-focused as the bank expanded both the number

of branches and the staff to run them. Equity had deliberately cultivated its brand and culture

over more than a decade of operations. It was becoming more challenging (yet no less

important) to instill the customer-service values in each new employee, and to monitor their

performance in exhibiting these values. As growth continued at an accelerating rate, Mwangi

thought that replicating the customer experience in increasingly far-flung locations would be

tricky. It was difficult for regional managers to travel to some of these locations. In addition,

although Kenya had made substantial progress building out infrastructure, basic business needs

including a constant supply of electricity and access to the Internet, continued to be only

inconsistently available throughout the country, somewhat limiting smooth and regular

communication.

Case Study:

Equity Bank

Case Study:

Equity Bank

Mwangi’s association with the bank began in 1992, when a founder (who was also a family

friend) urged him to deposit his savings in what was then a struggling indigenous enterprise

called Equity Building Society (EBS). Mwangi agreed, both to help keep a Kenyan institution

afloat and because he felt personally invested in its management team. He then watched EBS

continue to decline at an alarming rate. In 1994, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) found EBS

to be technically insolvent with poor management and inadequate board supervision. Equity

officials agreed to overhaul the firm’s strategy and operations in exchange for avoiding

dissolution. In 1995, Mwangi decided to get personally involved in turning Equity around. With

several years of experience working for Ernst & Young and Trade Bank, he joined EBS as the

finance director, and worked his way up to become CEO in 2004. During his time at Equity, he

oversaw its massive transformation from a small, insolvent mortgage lending company, to a fast-growing,

internationally recognized financial services bank. Throughout the organization’s

evolution, it had focused exclusively on Kenya’s economically marginalized citizens, the so-called

“unbanked” population. It was a remarkable turnaround story. With hours to go before

reaching his home, Mwangi reflected on the bank’s history as well as the challenges that lay

ahead.

Mwangi’s association with the bank began in 1992, when a founder (who was also a family

friend) urged him to deposit his savings in what was then a struggling indigenous enterprise

called Equity Building Society (EBS). Mwangi agreed, both to help keep a Kenyan institution

afloat and because he felt personally invested in its management team. He then watched EBS

continue to decline at an alarming rate. In 1994, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) found EBS

to be technically insolvent with poor management and inadequate board supervision. Equity

officials agreed to overhaul the firm’s strategy and operations in exchange for avoiding

dissolution. In 1995, Mwangi decided to get personally involved in turning Equity around. With

several years of experience working for Ernst & Young and Trade Bank, he joined EBS as the

finance director, and worked his way up to become CEO in 2004. During his time at Equity, he

oversaw its massive transformation from a small, insolvent mortgage lending company, to a fast-growing,

internationally recognized financial services bank. Throughout the organization’s

evolution, it had focused exclusively on Kenya’s economically marginalized citizens, the so-called

“unbanked” population. It was a remarkable turnaround story. With hours to go before

reaching his home, Mwangi reflected on the bank’s history as well as the challenges that lay

ahead.

Kenya was declared a British colony in 1920. Shortly thereafter, indigenous Kenyans were

banned from political participation. In the early 1950s a rebellion against colonial power began

and continued throughout the decade. The Kenya African National Union (KANU) party was

formed out of the struggle and in 1963, the country transitioned to independence. Jomo

Kenyatta, the leader of KANU became president and remained in power for 15 years. Kenyatta’s

government promoted capitalist economic policies and extensive investments in infrastructure.

He also focused his foreign policy on establishing strong relations with the Western world,

which led to foreign private investment and external economic assistance. For most of

Kenyatta’s tenure, the economy grew at an annual rate of 5 - 8 percent.

Kenya was declared a British colony in 1920. Shortly thereafter, indigenous Kenyans were

banned from political participation. In the early 1950s a rebellion against colonial power began

and continued throughout the decade. The Kenya African National Union (KANU) party was

formed out of the struggle and in 1963, the country transitioned to independence. Jomo

Kenyatta, the leader of KANU became president and remained in power for 15 years. Kenyatta’s

government promoted capitalist economic policies and extensive investments in infrastructure.

He also focused his foreign policy on establishing strong relations with the Western world,

which led to foreign private investment and external economic assistance. For most of

Kenyatta’s tenure, the economy grew at an annual rate of 5 - 8 percent.

After 24 years in power, Moi’s rule came to an end in December 2002, when the first fully

democratic elections were held.

Mwai Kibaki, from the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC),

became Kenya’s next president. In contrast to Moi’s authoritarian style, Kibaki espoused a

laissez-faire approach. He gave ministers broad mandates to run their respective governmental

areas, a strategy that led to some fragmentation of objectives and conflicts of interest among rival

factions within the ruling coalition. Nonetheless, under President Kibaki’s leadership, Kenya

began an ambitious economic reform plan, which promised reduction of government,

privatization of state-owned companies and deregulation of select industries. Some of these ideas

were quickly legislated. However, in general, related progress has been slow.

After 24 years in power, Moi’s rule came to an end in December 2002, when the first fully

democratic elections were held.

Mwai Kibaki, from the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC),

became Kenya’s next president. In contrast to Moi’s authoritarian style, Kibaki espoused a

laissez-faire approach. He gave ministers broad mandates to run their respective governmental

areas, a strategy that led to some fragmentation of objectives and conflicts of interest among rival

factions within the ruling coalition. Nonetheless, under President Kibaki’s leadership, Kenya

began an ambitious economic reform plan, which promised reduction of government,

privatization of state-owned companies and deregulation of select industries. Some of these ideas

were quickly legislated. However, in general, related progress has been slow.

Kenya has historically served as the main communication, trade and financial hub of East Africa.

This has resulted in relatively modern transportation and telecommunications infrastructure

compared with peer countries in the region. Although historical growth has been uneven, the

country has been on more solid economic footing since 2002. GDP growth rates increased from

2.8 percent in 2003 to 5.8 percent in 2005. Sectors such as tourism and

telecommunications expanded quickly during this timeframe and the trend appeared likely to

continue. The energy, construction and manufacturing sectors also grew steadily. In the banking

sector, asset quality strengthened and improved credit risk management contributed to an

increase in overall profitability of banks, with an average return on equity (ROE) of 24.4 percent

in 2005.

Kenya has historically served as the main communication, trade and financial hub of East Africa.

This has resulted in relatively modern transportation and telecommunications infrastructure

compared with peer countries in the region. Although historical growth has been uneven, the

country has been on more solid economic footing since 2002. GDP growth rates increased from

2.8 percent in 2003 to 5.8 percent in 2005. Sectors such as tourism and

telecommunications expanded quickly during this timeframe and the trend appeared likely to

continue. The energy, construction and manufacturing sectors also grew steadily. In the banking

sector, asset quality strengthened and improved credit risk management contributed to an

increase in overall profitability of banks, with an average return on equity (ROE) of 24.4 percent

in 2005.

Microfinance is the supply of basic financial services to the poor, including loans, credit,

savings, insurance and transfer services. The formal financial sector has not traditionally been

accessible to the impoverished entrepreneurs who comprise most of the world’s working

population. Instead, informal systems and relationships, including neighbors, and rotating

savings/ credit clubs, have filled this gap. While similar solutions have worked for some and are

often the only option available, they can be inconsistent and unreliable during times of

tremendous need. In addition, poor entrepreneurs can become trapped in vicious cycles of

borrowing from local moneylenders, who may demand exorbitant interest rates.

Microfinance is the supply of basic financial services to the poor, including loans, credit,

savings, insurance and transfer services. The formal financial sector has not traditionally been

accessible to the impoverished entrepreneurs who comprise most of the world’s working

population. Instead, informal systems and relationships, including neighbors, and rotating

savings/ credit clubs, have filled this gap. While similar solutions have worked for some and are

often the only option available, they can be inconsistent and unreliable during times of

tremendous need. In addition, poor entrepreneurs can become trapped in vicious cycles of

borrowing from local moneylenders, who may demand exorbitant interest rates.

Traditionally, banks were unwilling to provide loans to poor entrepreneurs due to the perceived

risk. Common concerns included the fact that the unbanked were often illiterate, had no

collateral, no prior credit history, and were not employed by anyone other than themselves.

However, in 1976, Mohammed Yunus, seen by many as the visionary behind the microfinance

movement, bucked conventional wisdom and loaned the equivalent of $27 of his own money to

an entire village of poor craftsmen in Jobra, Bangladesh. After all of the borrowers repaid, he

repeated the experiment with more villages, and over the years, grew his series of experiments

into a multi-billion dollar bank that has provided small loans to over 5 million people worldwide.

Around this same time, leading microfinance institutions (MFIs) including ACCION and

Opportunity International were also emerging, basing their work on the same bold ideas as

Yunus: that the poor could reliably repay their loans, with interest, and could use the profits to

grow their businesses.

Traditionally, banks were unwilling to provide loans to poor entrepreneurs due to the perceived

risk. Common concerns included the fact that the unbanked were often illiterate, had no

collateral, no prior credit history, and were not employed by anyone other than themselves.

However, in 1976, Mohammed Yunus, seen by many as the visionary behind the microfinance

movement, bucked conventional wisdom and loaned the equivalent of $27 of his own money to

an entire village of poor craftsmen in Jobra, Bangladesh. After all of the borrowers repaid, he

repeated the experiment with more villages, and over the years, grew his series of experiments

into a multi-billion dollar bank that has provided small loans to over 5 million people worldwide.

Around this same time, leading microfinance institutions (MFIs) including ACCION and

Opportunity International were also emerging, basing their work on the same bold ideas as

Yunus: that the poor could reliably repay their loans, with interest, and could use the profits to

grow their businesses.

Most borrowers of microcredit loans are women. In 2006, just over 3,100 microcredit

institutions reported reaching 113.2 million clients, 81.9 million of whom were among the

poorest when they took their first loan.6 Of these poorest clients, 84.2 percent are women.

Women have proven themselves to repay more consistently than male borrowers. Additionally,

women are seen as ideal clients due to the perception that they are more disciplined about

reinvesting profits back into their businesses, or to improving their family’s standard of living

(e.g., health and nutrition, education for their children).

Most borrowers of microcredit loans are women. In 2006, just over 3,100 microcredit

institutions reported reaching 113.2 million clients, 81.9 million of whom were among the

poorest when they took their first loan.6 Of these poorest clients, 84.2 percent are women.

Women have proven themselves to repay more consistently than male borrowers. Additionally,

women are seen as ideal clients due to the perception that they are more disciplined about

reinvesting profits back into their businesses, or to improving their family’s standard of living

(e.g., health and nutrition, education for their children).

Equity Bank was founded as Equity Building Society (EBS) in October 1984 and was originally

a provider of mortgage financing for the majority of Kenyans who fell into the low income

population.

The society’s logo, a modest house with a brown roof, was meant to resonate with

its target market and their determination to make small but steady gains toward a better life.

Despite its well-intentioned mission, EBS went through significant turmoil during the next

decade. The firm’s decline, although exacerbated by a downturn within Kenya’s banking sector,

was primarily self-inflicted.

Equity Bank was founded as Equity Building Society (EBS) in October 1984 and was originally

a provider of mortgage financing for the majority of Kenyans who fell into the low income

population.

The society’s logo, a modest house with a brown roof, was meant to resonate with

its target market and their determination to make small but steady gains toward a better life.

Despite its well-intentioned mission, EBS went through significant turmoil during the next

decade. The firm’s decline, although exacerbated by a downturn within Kenya’s banking sector,

was primarily self-inflicted.

EB’s lending rate was high compared to the sector’s average of 13.7 percent because of the

profile of its borrowers and the focus on microcredit. Equity made loans

available to all account holders once they had been deposit customers for at least six months.

Both the size of the loan and its repayment schedule were customized to each applicant by

specially trained branch credit officers. In 2006, EB loans ran from KSh 500 to over KSh 50

million depending on each applicant’s ability to repay.

EB’s lending rate was high compared to the sector’s average of 13.7 percent because of the

profile of its borrowers and the focus on microcredit. Equity made loans

available to all account holders once they had been deposit customers for at least six months.

Both the size of the loan and its repayment schedule were customized to each applicant by

specially trained branch credit officers. In 2006, EB loans ran from KSh 500 to over KSh 50

million depending on each applicant’s ability to repay.

Since 2002, Equity Bank managers pushed to scale as quickly as possible. The number of

branches expanded from 13 in 2002 to 42 in 2006, with 70 anticipated by 2008.

This was a significant roll out, given that Barclays Bank of Kenya (Barclays), the largest

financial institution in the country, only had 58 branches in 2006.

Since 2002, Equity Bank managers pushed to scale as quickly as possible. The number of

branches expanded from 13 in 2002 to 42 in 2006, with 70 anticipated by 2008.

This was a significant roll out, given that Barclays Bank of Kenya (Barclays), the largest

financial institution in the country, only had 58 branches in 2006.

EB outfitted branded, armored trucks to serve as mobile branches in rural locations that did not

yet have enough foot traffic to support a permanent location. A mobile branch

manager and staff would drive in the banking van to one of five sites each week, returning to the

same “home” branch each evening. A pared down set of deposits and loans were offered and the

mobile branch manager used a lean version of Equity’s IT system to process transactions. EB

expanded security for these automobiles (when car jackings became more frequent in the early

2000s) by assigning an armed guard and chaser cars to each.

EB outfitted branded, armored trucks to serve as mobile branches in rural locations that did not

yet have enough foot traffic to support a permanent location. A mobile branch

manager and staff would drive in the banking van to one of five sites each week, returning to the

same “home” branch each evening. A pared down set of deposits and loans were offered and the

mobile branch manager used a lean version of Equity’s IT system to process transactions. EB

expanded security for these automobiles (when car jackings became more frequent in the early

2000s) by assigning an armed guard and chaser cars to each.

The Finacle system covered daily bank processes and products for consumer banking, including:

savings and checking, deposits and consumer lending as well as those required for corporate

banking and trade finance. It linked the branches, ATMs and mobile banking channels back to

the centralized head office for data collection and management. Prior to rolling out the solution,

the company invested an additional KSh 17 million into training the entire organization on how

to use it.

The Finacle system covered daily bank processes and products for consumer banking, including:

savings and checking, deposits and consumer lending as well as those required for corporate

banking and trade finance. It linked the branches, ATMs and mobile banking channels back to

the centralized head office for data collection and management. Prior to rolling out the solution,

the company invested an additional KSh 17 million into training the entire organization on how

to use it.

Equity used a high-touch approach to acquire account-holders and retained them by offering

exemplary customer service. EB’s retail customers were primarily small-scale farmers (e.g.,

dairy, rice and tea), entrepreneurs and low-end salaried workers. These

“average” Kenyans, roughly 80 percent of the country’s population, often lived below the

poverty line as defined by Western standards. The firm’s positioning statement summed up the

brand attributes it used to appeal to this formerly unbankable population: “Equity Bank provides

accessible, customer-focused banking services for microfinance clients to meet their aspirations

for today and tomorrow. Unlike other financial institutions, Equity is down-to-earth and

friendly.” EB also espoused twin mottos of “the listening, caring financial partner,” and,

“growing together in trust.”

Equity used a high-touch approach to acquire account-holders and retained them by offering

exemplary customer service. EB’s retail customers were primarily small-scale farmers (e.g.,

dairy, rice and tea), entrepreneurs and low-end salaried workers. These

“average” Kenyans, roughly 80 percent of the country’s population, often lived below the

poverty line as defined by Western standards. The firm’s positioning statement summed up the

brand attributes it used to appeal to this formerly unbankable population: “Equity Bank provides

accessible, customer-focused banking services for microfinance clients to meet their aspirations

for today and tomorrow. Unlike other financial institutions, Equity is down-to-earth and

friendly.” EB also espoused twin mottos of “the listening, caring financial partner,” and,

“growing together in trust.”

Equity began sending employees into rural areas to educate

potential clients about its offerings. In order to best reach locals, EB representatives set up

booths in open air markets, hosted free mass public “financial training and education days”

and established a presence at community agricultural trade fairs.20 They also

conducted focus groups discussions and surveys.

Equity began sending employees into rural areas to educate

potential clients about its offerings. In order to best reach locals, EB representatives set up

booths in open air markets, hosted free mass public “financial training and education days”

and established a presence at community agricultural trade fairs.20 They also

conducted focus groups discussions and surveys.

After Mwangi took over as CEO in 2004, the number of deposit clients more than doubled

within two years. Revenue increased by over 300 percent during that timeframe,

from KSh 1,035 million to KSh 3,371 million and pretax income more than quintupled, from

KSh 218 million to KSh 1,103 million. In addition, the pretax margin rose from 21 percent to 33

percent due to effective control of personnel and bad debt provisioning spend.

After Mwangi took over as CEO in 2004, the number of deposit clients more than doubled

within two years. Revenue increased by over 300 percent during that timeframe,

from KSh 1,035 million to KSh 3,371 million and pretax income more than quintupled, from

KSh 218 million to KSh 1,103 million. In addition, the pretax margin rose from 21 percent to 33

percent due to effective control of personnel and bad debt provisioning spend.

In 2006, Equity was the seventh largest bank out of 45 operating in Kenya based on profit, yet it

only had 3 percent market share of loans and deposits. Due to the relatively

limited means of EB customers, the average deposit account held just 10 percent of the value in a

typical customer’s account at larger banks including Barclays and Kenya Commercial. Yet, the

bank gained 14 percent of new deposits in 2006. Although some industry commentators feared

an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs) as the EB’s asset base increased, the quality of the

loan book as represented by the ratio of non-performing loans and advances to gross loans and

advances actually improved markedly from 10 percent in 2005 to 5 percent in 2006.22

In 2006, Equity was the seventh largest bank out of 45 operating in Kenya based on profit, yet it

only had 3 percent market share of loans and deposits. Due to the relatively

limited means of EB customers, the average deposit account held just 10 percent of the value in a

typical customer’s account at larger banks including Barclays and Kenya Commercial. Yet, the

bank gained 14 percent of new deposits in 2006. Although some industry commentators feared

an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs) as the EB’s asset base increased, the quality of the

loan book as represented by the ratio of non-performing loans and advances to gross loans and

advances actually improved markedly from 10 percent in 2005 to 5 percent in 2006.22

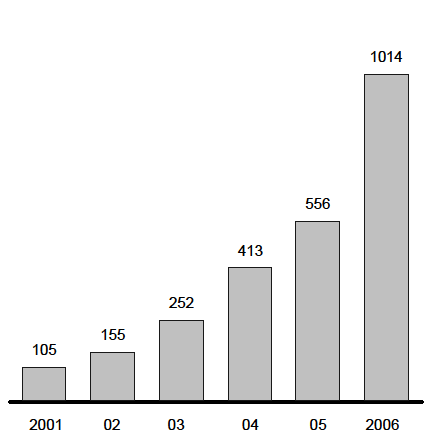

In an effort to drive sales, the number of staff expanded from 117 in 2000 to 1,394 in 2006, with

the biggest increases in the last two years. Yet, although annual management

expenses increased by 85 percent from 2004 to 2005 and by 78 percent from 2005 to 2006, this

line item stayed relatively constant as a percentage of net revenue. Helped by EB’s

comparatively attractive spread between lending and savings rates, Equity’s profit before tax

increased even faster than sales during this six year time period, from KSh 33.6 million in 2000

to KSh 1.1 billion in 2006.

In an effort to drive sales, the number of staff expanded from 117 in 2000 to 1,394 in 2006, with

the biggest increases in the last two years. Yet, although annual management

expenses increased by 85 percent from 2004 to 2005 and by 78 percent from 2005 to 2006, this

line item stayed relatively constant as a percentage of net revenue. Helped by EB’s

comparatively attractive spread between lending and savings rates, Equity’s profit before tax

increased even faster than sales during this six year time period, from KSh 33.6 million in 2000

to KSh 1.1 billion in 2006.

Bethany Coates prepared this case with cooperation from Ana Garcia Azuelo, Jessica Flannery, Haydee Moreno and Professor Garth Saloner as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

Bethany Coates prepared this case with cooperation from Ana Garcia Azuelo, Jessica Flannery, Haydee Moreno and Professor Garth Saloner as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.