The design of a compliant composite crutch Dorota Shortell, MSME; Jeff Kucer, MSME; W. Lawrence Neeley, BSME; Maurice LeBlanc, MSME, CP Stanford University, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Design Division, Stanford, CA 94305; Rehabilitation Research and Development Center, Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA 94304.

Abstract Ambulation by crutches takes up to twice the energy of normal gait and can lead to injuries of the hands and arms. The compliant composite forearm crutch described in this article seeks to address these problems. The new crutch is made of a single composite piece and has an S-curve in the main body to provide shock absorption and return of energy with the goal of reducing impact and repetitive injuries. It is lighter and, we expect, more durable than current crutches due to the lack of interfacing parts. The new forearm cuff design provides retention of the crutch on the arm without a pivot. The contoured forearm cuff with wrist supports and padding is intended to provide added comfort and support. These features are integrated into an aesthetic, high-tech looking design in charcoal/black color. (See Figure 1). Initial testing with seven users yielded favorable response in function and appearance. Quantitative analysis has identified improvements needed for future iteration in design. These include (1) making the wrist supports more narrow and placed down one inch, (2) optimizing the stiffness of the top curve of the S-shape and (3) testing the crutch for motion and energy requirements in use. Key Words: crutch, forearm, S-curve, compliance, shock absorption, composite material, cuff, spring return. This project is based upon work supported by the Rehabilitation R&D Center at the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Palo Alto with funding from the DOD Ballistic Missile Defense Organization. It was conducted as a Stanford University mechanical engineering graduate class (ME 310) design project. Address all correspondence and requests for reprints to: Maurice LeBlanc, Rehabilitation Research and Development Center (MS-153), DVA Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA 94304: email: leblanc@roses.stanford.edu.

Figure 1. CAD model of the final crutch geometry Introduction Background Crutches, in one form or another, have been used for 5000 years (1). From fallen tree branches used to assist balance and ambulation, they have evolved into their present configurations of underarm and forearm crutches. The materials have changed, but the overall design of the crutch is largely the same. They are basically sticks with hand and underarm or forearm supports. Current crutch designs present some problems for users:

Objective The goal of this project was to ameliorate the problems, as describe above, faced by users of crutches. The target user group chosen was permanent users because they have long term and constant need for improvements in crutch design. (Most permanent users utilize forearm crutches whereas most temporary users utilize underarm crutches.) Summary of Previous Investigations This project was preceded by one which compared different kinds of underarm or axillary crutches (11). Four experimental designs of axillary crutches were tested by users and compared to standard underarm and forearm crutches. The four experimental designs were:

These four designs were tested with users and compared with standard underarm and forearm crutches. Results showed no significant improvement in energy consumption, and therefore none of the designs were selected for further development. Methods The project described in this article was conducted largely by Stanford graduate students as part of a three-quarter design class (25). Needs Assessment: The first step was to conduct interviews to evaluate current crutch shortcomings. The interviews with crutch users helped to generate a list of design requirements as follows:

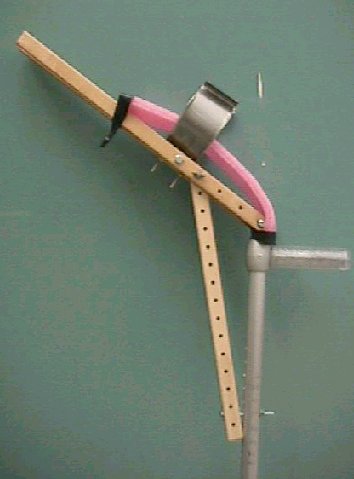

Testing of Design Ideas Several quick prototypes were built to test ideas. The first of these was an angled-cuff prototype. Angling of forearm support should serve to decrease the load placed upon the hands and wrists. Essentially, the amount of load shifted from the hand and wrist to the forearm is a direct function of the angle at which the forearm is placed relative to the vertical. The angled cuff prototype (See Figure 2) allowed exploration of the effect of various placement angles upon the function of a single crutch. The prototype allowed adjustment between 20 and 90 degrees in five-degree increments. This concept also has been explored by Nils Hagberg (27).

Figure 2. Angled cuff prototype A wrist support prototype was produced in response to the pain felt in the hands and wrists of crutch users, caused by the force used to grasp the crutch. As observed in user testing, high grip force is used to maintain stability when the maximum load is applied. To compensate, bracing elements (See Figure 3.) were positioned on either side of the wrist to stabilize it and allow a more relaxed grip on the handle. Though the design goal was achieved with this prototype, user testing revealed concerns of possible injury resulting from the inability of a user to disengage from the crutch during a fall. (Future iterations of the prototype did not curve around the wrist, but rather were left open for easy arm removal.)

Figure 3. Wrist support prototype A study was conducted to assess the geometry of the forearm support to offer the user increased comfort and support. Working under the assumption that the cuff would take the general form of a sleeve or trough that cradled the arm, plaster casts were created of forearms and used as molds to create positive right and left models that were the size and shape of the forearms. Forearm supports were created by heating 0.2 inch thick rectangular sheets of ABS plastic and forming them over the models. The wrist supports eventually were integrated into the cuff. (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forearm support prototypes An extensive spring study was conducted to determine the spring rate and travel that are optimal for a crutch. The users who were interviewed expressed the need for shock absorption in their crutches. Thirty linear compression springs, with constants ranging from 55 to 409 lb./in, were evaluated by putting them into crutches and testing them with users. The following results were obtained:

A graph with suggested spring constants for body weight is shown in Figure 5. This graph was developed by taking the qualitative results of user testing and fitting a trendline, called the target value. There is an upper and lower bound to reflect different user preferences determined by maximums and minimums. A spring constant that addresses the needs of the majority of users is 125 lb./in. Referring to the graph, this spring constant, while ideal for a 157-lb. person, is also suitable for people weighing 117 to 198 lbs. This range covers 83% of the female population and 79% of the male population (28). The 125 lb./in. spring will travel 0.628 inches for a 157 lb. person. 125 lb./in. and 0.6 in. travel were selected as the design target. The final crutch design assumes customized compliance for different weight classes.

Figure 5. Suggested Spring Constant for Adults Integrating the Design Ideas into a First Prototype Crutch The goal of the integrated prototype was to incorporate the desired design features into a pair of functional, testable, prototype crutches. A pair of fiberglass crutches that contained helical compression springs and a 45-degree angle cuff was constructed (See Figure 6).

Figure 6. Integrated prototype crutch The inner core of the prototype was made with a 125 lb./in metal spring press fitted between two wooden rods and secured with epoxy. A block of foam was shaped to create the forearm cuff. The entire crutch core, except for the spring, was laminated with strips of fiberglass cloth dipped in epoxy resin. Concentric carbon fiber tubes shielded the spring. The rough surfaces and exposed fiberglass fibers were sanded and a final coat of resin was applied for a smooth surface finish. A 45-degree forearm angle was chosen for this prototype in an effort to examine the effects of a forearm cuff angle that was furthest from conventional crutches. The following conclusions were made from testing this first prototype.

Final Prototype The final design was created in three-dimensional CAD. Features identified in the first prototype were incorporated into the final design. Additional design requirements addressed were durability, light weight, ease of object reach, comfort, quiet use, and aesthetics. Carbon fiber composite material was used to fabricate the final design. This approach allowed the spring mechanism to be integrated into the body of the crutch itself, and the entire crutch could be made from one part. We learned that Ergonomics, Inc. also has made forearm crutches of composite material, but used standard round tubes (29). For incorporating shock absorption directly into the body of the crutch while maintaining a single-piece design, inspiration was taken from prosthetic feet that use combinations of composite material leaf springs to achieve compliance (30). After trials with different geometry configurations, the design team decided on a S-curve design. Compliance was achieved by the two arcs of the S-curve deflecting and acting as a spring. As force is applied, each curve compresses to absorb shock. As force is unloaded, the crutch returns to its original position and returns kinetic energy. Finite element modeling was used to determine the thickness of the composite cross-section and the amount of curvature that would give the desired compliance (31). Since the S-curved body has a rectangular cross-section, the problem of attaching a conventional crutch tip was addressed by tapering the end of the crutch so that it transformed to a circular cross-section. The handle was incorporated as a simple rod, allowing handgrips of any style to be slipped over it. The last step in the design was figuring out the geometry for the elbow cuff. The final solution has the two sides of the cuff extending up and around the top of the forearm until the ends are about 2 inches apart. The sides are flexible to act as a quick-release mechanism. The posterior underside of the cuff is cut out, thus allowing the crutch to hang vertically as a user flexes his/her elbow. The cuff is curved around the arm and padded to provide support and comfort. The forearm support is at a 30-degree angle and has supports positioned on either side of the wrist joint. The final CAD geometry of the crutch and a close-up of the cuff area are shown in Figure 1. Results Manufacturing Sparta Inc. (32), an R&D company with offices in San Diego, CA that designs and develops composite material products, made the Stanford student designed crutches using a wet layup method with three different graphite material weaves:

A mold was constructed by precision cutting a piece of wood using a CNC milling machine to the geometry given in the CAD model of the crutch . The fibers were placed on the mold and coated with resin (See Figure 7).

Figure 7. Fully layed-up crutch on the model The final crutches are 0.32 inches thick in the curved section and weigh 20 oz. each without tips or padding. Since the lay-up was not pressurized in the curing, approximately 33% less fiber volume and weaker material properties were achieved than if production methods had been used. Production methods would yield a higher fiber volume, meaning that the same performance could be achieved with a thinner crutch. It is estimated that a final production crutch would weigh only 16 oz. Once the main body was finished, tips, handgrips, and padding for the cuff were attached. Conventional rubber tips and handgrips were used. Custom-made padding was attached to the forearm support using spray adhesive. The final crutches are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Final crutches User Testing Quantitative testing: weight, thickness, spring constant, center of weight, bending profile, etc. were measured in the laboratory before user testing. Both static and dynamic loads of up to 250 lbs. were successfully applied to the crutches prior to user testing. User profiles: age, disability, type of crutches, problems in use, etc. was acquired from the subjects before they tested the crutches in use. All users were aged 41-55 with an average age of 46.5 years. Five of the six users had post polio and one user had cerebral palsy. All were users of forearm crutches. User testing: the six subjects were given time to get acquainted with the new crutches and test them in use. Then a questionnaire was administered with 15 topics using a Likert Scale of 1 to 7 with 7 being the best. Highlights of their feedback are as follows:

Overall, user feedback indicated that the general design appears to be an improvement over current forearm crutches, but improvements are necessary to meet their all their needs. Biomotion Laboratory Testing Experimental testing was done in the Stanford University Biomotion Laboratory (33). The crutch was loaded from zero to 100 pounds over a period of two seconds. The force applied to the ground and the three-dimensional position of the photo-reflectors attached to the crutch were measured. From this data, it was possible to calculate the stiffness of the entire crutch and the S-curved portion as 43 lb./in. and 211 lb./in., respectively. The resulting stiffness values showed that the crutch is deflecting in two different manners. The first deflection is in the S-curve and is what was originally planned for. The second deflection is due to the bending of the cuff posteriorly. This latter of deflection causes the crutch to be more compliant and creates a feeling of instability in heavier users. Finite Element Model The goal of the finite element analysis after user testing was to optimize the bending behavior for the crutches. It was found that the level of deflection in the S-curve was dwarfed by the bending moment created by the cuff at the top of the crutch. The finite element software ANSYS was used to run the analysis (31). There were four possible parameters that could reduce cuff bending: increasing the thickness of the upper curve, decreasing the cuff angle, reducing the amount of curvature of the top curve, and changing the apex of the top curve. Changing the thickness of the upper curve was undesirable since it would complicate the manufacturing process. Decreasing the cuff angle was unfavorable because the hands would have to carry more load. Therefore, the solution was chosen to change the curvature and apex of the top curve. The final optimization moved the top curve up 1.0 inches and inward 0.5 inches.

Figure 9. Two-dimensional finite element representation of original curve of crutch (left) and optimized curve (right). Discussion The final design of the compliant composite crutch addresses some of the needs expressed by permanent crutch users. Its single-piece composite design reduces noise. Shock absorption and energy return are addressed with the S-shaped body that acts like a spring. The energy that is stored in the beginning of the gait cycle theoretically is returned to the user at the end of the gait cycle. Energy testing is needed to confirm that assumption. The forearm cuff design gives added support and comfort, while allowing users to maneuver and reach for objects. Users liked the charcoal/black, high-tech appearance of the crutches. Future Improvements The positive responses from testing by crutch users of the compliant composite crutch are encouraging. However, this design must go through additional design iteration before it is ready as a product. Needed improvements include:

Vision of Final Product Ultimately, the crutch may be a semi-custom product that is selected for each individual, much like the FlexFoot in lower limb prosthetics (30). The S-curve of the crutches can be made in different thicknesses to achieve desired compliance for users of different weights, such as light, medium and heavy. The crutches would be cut to length on the height of the crutch from floor to handgrip. I. e., all crutches could be manufactured at the longest possible length and then cut to the size for each user. The fitting of the cuff could be addressed by making a large cuff with accommodation for smaller forearms by using extra padding. Users could specify handgrips and tips of choice. The relatively high cost of manufacturing the crutches is a potential problem. Composite materials are typically high in cost. To keep the crutches reasonably priced, manufacturing processes would have to be further explored. Possibilities include using fiberglass instead of carbon fiber and making the S-curve of composite material with the forearm cuff made separately by a one-piece injection molded part. An idea for improving the design of the crutch is to make it foldable. Many crutch users want their crutches to be compact for travel or storage. This design could be adapted to fold in half by adding a hinge between the two curves, at the point of lowest stress, so that one curve nests in the other curve. Another suggestion by one of the crutch testers is to place a small reflector on the end of the handgrip and on the back of the forearm cuff for visibility at night. Conclusions The compliant composite crutch prototype addresses many of the concerns of crutch users. Their positive feedback is encouraging. However, the potential benefits must be proved and documented with further study. Design improvements, as discussed above, need to be implemented. The goal is that through further redesign, analysis, and testing, the compliant composite forearm crutch will offer improvement to permanent crutch users. Acknowledgements We would like to thank:

References

|