Chierika Okugu

Infancy is a time of significant growth and change that provides settings for interactions that influ- ence a child’s growth and development. Language development in the early years of life

depends on verbal input from caregivers, and variations in verbal input among mothers may result in developmental differences in infants.1,2 Researchers have looked at mother-infant dy- ads from different socioeconomic statuses (SES) in America as well as in Africa to garner these results. In Senegal, there is anecdotal evidence that some parents believe that talking to young infants attracts jealous spirits that possess the child and cause harm.3 These beliefs suggest that Senegalese mothers may speak to children less to protect them from malevolent spirits. This study aims to understand the verbal interactive styles of rural Senegalese mothers and their chil- dren. Previous studies have linked the amount of maternal speech directed at the child to a child’s overall rate of vocabulary development.4 Identifyingthe quantity of language and the com- municative styles of Senegalese mothers, and then comparing them to previous studies done by various researchers in American and other African early language environments will help position the rural Senegalese dyads in relation to these varied cultures. To assess interactions, audio-visual recordings of naturalistic observa- tions during a controlled play session were con- ducted. The quantitative and qualitative aspects of speech to Senegalese children during this play session were then compared to studies with similar methodology. These data were collected as part of the Stanford-Tostan Evaluation Project (STEP).Understanding the Senegalese early lan- guage interactions could pave the way for further studies that identify how the amount and type of verbal input from mothers to their children are related to children’s language proficiency and, moreover, school outcomes for 22-25-month-

olds in Senegal.

The Importance of Child-Directed Speech in Language Development

A child’s experiences with language in the early stages of life have been shown to predict sub- sequent learning capabilities.1,2 Each child’s early language environment is unique not only because of differences in the amount of speech each child hears, but also differences in how par- ents tend to the child’s attentional focus by using verbal devices such as questions, directives, and praise. Early research linked this variation in child- directed speech to influencing a child’s ability to learn tasks and develop vocabulary.5 Vocabulary development has been linked to the development of expressive language, IQ, and working memory, which have all been further linked to positive school outcomes.4,6 Thus it is important to understand how much speech Senegalese children receive as these factors are most influ- ential in children’s vocabulary development and further, implicated most with school outcomes.4

Qualitative Characteristics of Child-Directed Speech

The way that a mother wishes to verbally interact with her child is influenced by the same factors that influence the quantity of verbal interactions. Stylistic differences in maternal verbal interaction is a crucial element in variation in language de-velopment.7 Studies suggest Senegalese culture requires that mothers use language that has a regulatory function so that children are able to survive in a task-oriented society that values obedience.8 Directives, functionally serving to directly influence a child’s behavior, have this very function and were assessed in this study.

Language Development and School Outcomes

Language development is important for future academic and real-life success. Studies have shown a link between a child’s language development and success in school at later ages.4This study describes the early language environment in Senegal and compares its quantitative and qualitative characteristics to Western and other African language environments. It can serve as the basis for future studies on education and school outcomes in Senegal. In Senegal, there is a shift in the social framework toward a more ‘modernized’ society promoting a need for in- creased language proficiency in order for children to succeed in school.8 Therefore, development pathways must shift when more rural communities are influenced by urbanization and formal education.

Research Questions

The current study explored variation in the quantity and quality of child-directed speech in Senegal and how it compares to Western and other African early language environments. Naturalistic observations of Senegalese mother-infant dyads were conducted to assess the amount and type of child directed speech. The total number of maternal utterances and words were counted, and utterances functioning as either directives or praise were categorized and summed. These features were compared to research done by these studies had similar participants, methodology, and research aims.

METHODS

Participants

Participants

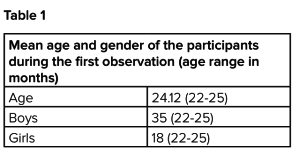

Participants were 49 monolingual mother-infant dyads from 17 villages in the Kaolack region of Senegal, whose native language is Wolof. Infants were 22-25 months old (average age= 24.12months), and native-Wolof speaking STEP field workers recruited these pairs.

Naturalistic Observations of Caregiver-Child Interaction

Mother-infant dyads participated in 15-minute play sessions at a village center. Dyads were seated together on a mat and given a standard set of six small toys. Mothers were instructed to stay on the mat and ‘play with their child as they would at home.’

Transcription

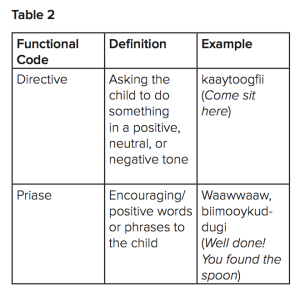

Maternal and child speech were transcribed during the play sessions following CHILDES guidelines (MacWhinney, 2007). The total number of maternal utterances, or uninterrupted chain of spoken language were summed. Number of words within these utterances was summed over the middle 5 minutes of the play session to assess the quantity of speech. Relevant utterances were further categorized into two functional categories as shown in Table 2.

Directives: Utterances meant to direct the infant’s attentional focus were categorized as directives. This category included imperatives and ques- tions (e.g. jogal: “get up” and dingatëdd: will you lie down). It also included implied directives in which the desired action was not explicitly iden- tified (e.g.Eli yangiyàqyëfujàmbur de: Eli you’re breaking somebody’s stuff).

Praise: Maternal utterances that featuredencour- agement or positive reinforcement of the child.

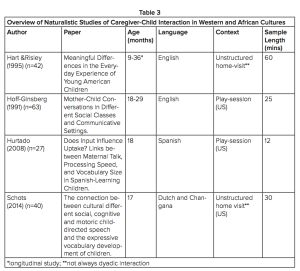

Standardizing Data

We standardized the results of research by Hart &Risley (1995), Dixon (1991), Hoff (1991), Hurtado et al. (2008), and Schots (2014) to accurately compare our data to these previous studies. Because the studies covered different types of culture, SES, and type of interaction, they captured a very broad look at mother-infant interactions (Table 3).

RESULTS

Comparison of Early Language Environments: Quantity

Comparison of Early Language Environments: Quantity

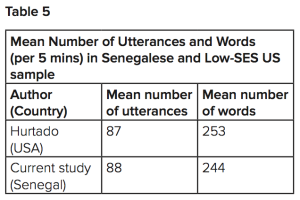

Table 5 shows that on average, low-SES mothers from Senegal and the US use a similar amount of utterances and words when speaking to their infants.

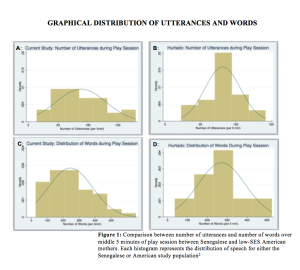

When looking more closely at the amount of speech in each cohort, Figure 1a shows, there was great variability among Senegalese mothers, with some mothers saying as few as 14 utterances during the 5 minutes and while other mothers are saying over 180 utterances during the middle five minutes. These results were similar to data gleaned from low-SES mothers from the US, which also showed similar variability and mean number of utterances (Figure 1b).

Graphical Distribution of Utterances and Words

Graphical Distribution of Utterances and Words

Figure 1c and Figure 1d above showed that both low SES-Americans and Senegalese mothers said up to 200 words. Note, however, that the distribution of number of words for the Senegalese mothers is left-skewed suggesting that more mothers used fewer words.

Comparison of Early Language Environments: Quality

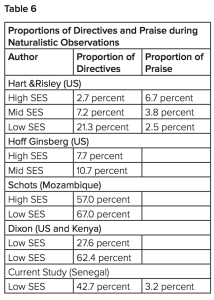

These data show that the Senegalese early language environment is highly variable but quite similar to one sample of children in low-SES US environments. Table 6 highlights the proportion of directives and praise used in the early language environments.

Directives

Directives

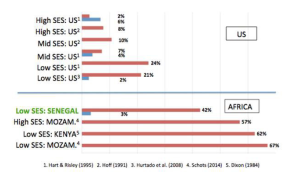

Given that each observation was conducted in a different context, it is difficult to compare the number of utterances across studies. However across all studies, Americans and Africans with lower SES generally used more directives than did higher and middle SES Americans. Figure 2 shows the proportion of directives for each study and highlights that on average, mothers direct their child’s attention more than they praise their children. It also shows that each African context had the highest proportion of directives. The results from this studyare most similar to that of high SES mothers from Mozambique. Also note the SES related differences in the proportion of directives used in the US, which supports previous research.

Praise

The study by Hart &Risley was the only one to look at rates of praise in a comparable way. At 3.2 percent, the proportion of praise for our Senegalese cohort was very low, as predicted, and is comparable to that of low SES Americans from Hart & Risley’s study.

Figure 2 showcases the relationship between SES and proportion of praise, and also shows that there is a much stronger tendency for Senegalese mothers to use more directives than their low-SES counterparts from the US.

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

On average, the amount of talk to infants among rural Senegalese caregivers was similar to that of low-SES Americans from Hurtado et al. (2008).10 There was considerable variation among rural Senegalese caregivers in their amount of childdirected speech. Senegalese mothers use more directives and less praise when interacting with infants.

Senegalese mothers used a large proportion of varied directives. This first example showcases directives that followed the child’s attentional focus and encouraged the overall interaction:

MOTHER: jëlal[5x]. translation: take[5x].

comments: the mother points at the toy and the child goes to take.

MOTHER: jëlalbii. translation:: take this one.

The second example shows directives used to redirect the child’s focus:

MOTHER: toogaltebàyyulingay def han.

translation:: sit down and stop what you’re doing han.

MOTHER: toogeelnii.

translation:: sit right here.

These examples exhibit the nuances in direc- tives provided to many Senegalese children in this sample.

Rates of praise in the Senegalese cohort were low and were usually given in response to the child’s successful completion of a task.

MOTHER: waawgóor, yaw yaabaax. translation : bravo, you’re so kind.

MOTHER: màggyemniisikaw. translation : may you grow like this.

This is addressed to children when they give something to adults.

When these findings are compared with past research, it appears that Senegalese mothers may not provide their children with a language environment that promotes cognitive development.1

CONCLUSION

The study described the level of child-directed speech during the playtime interactions that take place in Senegal. It replicated and expanded upon findings about African mother-infant interactions. It showed that Senegalese mothers spoke less in comparison to European-American mother infant dyads, and at levels comparable to the Gusii of Kenya.

Previous research has shown that interaction between the qualitative and quantitative aspects of speech could affect children’s vocabulary and cognitive development. Together, these data indicate that the early language environment of Senegalese infants may not be conducive to cognitive development necessary for school readiness.

References:

1 Hart, B., Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences ofyoung American children.Balti- more, MD: Brookes Publishing Company.

2 Hoff, E. (2003). The Specificity of Environmental Influ- ence: Socioeconomic Status AffectsEarly Vocabulary Development Via Maternal Speech. Child Development, 74(5),1368–1378.

3 Zeitlin, M. (2011) New Information on West African Tra- ditional Education and Approaches toits Modernization. Hewlett Foundation’ Global Development Program.

4 Marchman VA, Fernald A. (2008). Speed of word recogni- tion and vocabulary knowledge in infancy predict cognitive and language outcomes in later childhood. Developmental Science. 11, 9–16

5 Hess R D & Shipman V., (1967) Cognitive elements in ma- ternal behavior. Minnesotasymposia on child psychology. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. 1, 57-81.

6 Walker D. et al., (1994) Prediction of school outcomes based on early language production and socioeconomic factors. Child Development. 1994;65:606–621.

7 Masur, E. et al. (2005). Maternal Responsive and Directive Behaviors and Utterances as Predictors of Children’s Lexi- cal Development. Journal of Child Language, 32, 63-91.

8 Greenfield, P. M. (2009). Linking social change and de- velopmental change: Shifting pathways ofhuman develop- ment. Developmental Psychology, 45, 401–418.

9 Stanford Tostan Evaluation Project: Tostan is currently implementing interventions to improve school outcomes by facilitating community led efforts to enrich the early language environment through a 9-month parent educa- tion program which emphasizes the importance of verbal engagement with young children. The STEP evaluation study is assessing the efficacy of this new Tostan program using naturalistic observations, focus groups, surveys, and questionnaires. The evaluation measures based on natu- ralistic observations of 15-minute mother- infant playtimes interactions, questionnaires for language proficiency using a Wolof adapted version of MacArthur-Bates CDI, and the Looking While Listening (LWL) procedure.

10 Table 3 Comparative Studies:

Hoff-Ginsberg, E. (1991).Mother-Child Conversation in Dif- ferent Social Classes and Communicative Settings.Child Development, 62, 782-796.

Hurtado, N., Marchman, V., Fernald, A., (2008). Does Input Influence Uptake?Links between Maternal Talk, Processing Speed, and Vocabulary Size in Spanish-Learning Children. Development Science, 11, 31-39.

Schots, D., (2014).The Connection Between Cultural dif- ferent Social, Cognitive, Motoric Child-Directed Speech and the Expressive Vocabulary Development in Children. Tilbrug University, 2-36.

Dixon, S., (1991).Moter-Child Interaction around a Teaching Task: An African-American Comparison. Child Develop- ment, 55, 1252-1264

Image Citations

1. Image Courtesy of Chierika Ukogu and STEP Team Mem- bers

2. Figures: Generated by Chierika Ukogu using STATA software