On the front page...

NIH’s 35th annual observance of the life

and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., transformed

Masur Auditorium into a window on history with a bold

perspective by Dr. Clayborne Carson, director of the

King Research and Education Institute at Stanford

University.

The Jan. 17 program, titled “Remember!

Celebrate! Act!” honored what would have been King’s

77th birthday with song, image and story — only this

time, what might have been routine became a compelling

seminar, the sort of class students vie to attend as

they crowd around their favorite professor.

Continued...

|

|

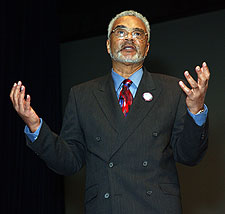

| Dr. Clayborne Carson

of Stanford University gives King keynote

address. |

|

“Remember Rosa Parks,” said Carson, emerging from

behind the lectern and walking to center stage, where,

speaking without notes, he set the audience at ease with

his gentle, courtly manner.

Then came the bracing follow-up: “If not for the

actions of Rosa Parks, Dr. King would’ve been a

wonderful minister at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church,

but we wouldn’t be talking about him today. And without

Coretta Scott King, there would be no King holiday, no

King papers nor King Institute.”

Carson, professor of history at Stanford University,

was tapped by Mrs. King to edit Dr. King’s papers. He

now directs the project and the recently established

King Institute, which is raising an endowment to ensure

that the project’s efforts continue in perpetuity.

“King didn’t do it alone,” Carson reminded his

listeners, recalling how the civil rights movement’s

genesis in the Montgomery bus boycott had been planned

by women such as Parks, a long-time NAACP worker and

secretary of its local chapter. Her refusal to give up

her seat was not spontaneous, but rather a

well-orchestrated tactic leading to a test case

challenging transit segregation. “And then the women

decided they needed a leader — that is, a man,” he noted

wryly — implying that, in the 1950s, any woman, however

capable, would have been rejected for such a powerful

role.

The audience nodded and murmured in assent as Carson

sketched out an argument that differed somewhat from the

“Great Man” theory of history. In focusing on community

struggle, he credited the women who spearheaded and

maintained the movement.

| |

|

| |

Guest speaker Carson

(l) visits with attendees following the MLK

program in Masur Auditorium. |

And who also benefited from that struggle. “Women

don’t always recognize that the 1964 Civil Rights Act

affected more non-black people — that is, women of other

races — than blacks,” the professor stated.

Indeed, there in evidence was Dr. Ruth Kirschstein,

senior advisor to the NIH director, whose introductory

remarks recalled her medical school days at Tulane in

then-segregated New Orleans. In solidarity with blacks

forced to sit behind buses’ color barriers, she never

sat down on a city bus during her years as a student

there.

“My classmates thought I was crazy,” she quipped,

“but it made me turn to a course that I have followed

here in Bethesda for the last 50 years.”

As director of the National Institute of General

Medical Sciences from 1974 to 1993, Kirschstein was the

first woman institute director at NIH. As prelude to the

keynote address, her opening remarks traced how

affirmative action advanced the standing of blacks and

women at NIH as it established its EEO program, the

Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Office of

Research on Minority Health and the National Center on

Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Meanwhile, in accompaniment, a slide show ran scenes

from King’s life. It was a poignant reminder of how

young and audacious he was — at 26, as the new minister

in the city of Montgomery, and with no experience in

civil rights leadership, he began his “Call to

Conscience.”

Even so, Carson asserted, King was not only a civil

rights reformer. “It was not just about riding in the

front of the bus,” he said, “but about being part of

anti-colonial struggles in Africa and Asia.” He noted

that King went to the Ghanaian independence ceremony as

the

|

|

| Stanford’s Carson

makes a point during his lecture. |

|

personal

guest of Kwame Nkrumah, first president of modern Ghana

and one of the most influential Pan-Africanists of the

20th century.

Carson then urged listeners to investigate for

themselves how colonialism, Jim Crow and apartheid were

vanquished. His hint: “Young people,” he said, “were

crucial.

“The Birmingham movement was a children’s crusade

because King was already in prison,” he said. “The

uprising in Soweto, South Africa, was launched by

teenagers; Nelson Mandela was in prison.”

From this international perspective, Carson urged his

audience to action by quoting one of King’s sermons

given the year before he was assassinated: “If you take

a stand for that which is right, you will never go

alone.”

So now, asked the professor, what entrenched social

evils in the world are young people of the twenty-first

century going to fight? “Are they going to eliminate

poverty? Will health care be distributed only to those

who have money?”

Speaking to his audience at NIH, those dedicated to

“medicine for the public,” he couldn’t have asked for a

better reception.