|

THE BARDS

OF THE 'BURBS

Does

poetry matter? A maverick pair of supporters says it can--and they're shaking

up the American literary scene from an unlikely base at West Chester University.

By CYNTHIA HAVEN

I 've never read

in front of so many smart people before!" the woman onstage coos into the

microphone. "I usually read in front of stupid people," she adds, to laughter

and applause.

Clad in a slinky

black dress lavishly decorated with red cabbage roses, the 40-ish brunette-who

has two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships and several published

books to her credit-sports a tattooed chameleon crawling across her left bicep.

A new look for modern poetry? Perhaps. But the face-lifting has less to do

with Kim Addonizio's appearance than with the sonnet-yes, a sonnet-she begins

to read:

What happened,

happened once. So now it's best

in memory-an orange

he sliced: the skin

unbroken, then

the knife, the chilled wedge

lifted to my mouth,

his mouth, the thin

membrane between

us, the exquisite orange,

tongue, orange,

my nakedness and his,

the way he pushed

me up against the fridge-

Her reading entrances

the audience, and not just because her poem is sexy, but also because it echoes

with cadences that have been familiar to English-speakers for centuries. In

a world where poetry has become almost irrelevant, Addonizio and the other

poets gathered at the annual West Chester Poetry Conference want to return

it to a general audience. Their weapons of choice? Traditional forms, rhyme

and meter, those age-old tools of the poet's craft, which fell out of fashion

in the last century but are making a startling comeback.

Co-founded by

a maverick California poet, Dana Gioia, and a local fine-press printer, Michael

Peich, the West Chester conference is perhaps the largest such ongoing symposium

in America, with more than 200 people attending in this, its sixth year. The

Philadelphia Inquirer has decreed it "a true event, one of the most

important such conferences in the United States." Over the years, it's pulled

in such heavyweights as Richard Wilbur-arguably America's greatest living

poet-and Anthony Hecht and Britain's Wendy Cope, among others. Together, Gioia

and Peich have made this small suburban campus into an unlikely literary mecca.

Not everyone

is a fan of what the West Chester conference represents. The movement that

gave birth to it-loosely called "New Formalism"-has been locked in a David-and-Goliath

struggle with several of the more powerful institutions in today's poetry

world. Notable among them is Philadelphia's prestigious American Poetry

Review, which in 1992 published a blistering attack on it as "dangerous

nostalgia" with a "social as well as a linguistic agenda." Another critic

labeled the group "the Reaganites of poetry." And a recent issue of the American

Poetry Review makes a dismissive reference to "neo-conservative formalism."

Yet Kim Addonizio,

in her plunging black dress, hardly looks like a Reaganite. Far from being

a privileged conservative, the onetime waitress writes of lonely lives, one-night

stands, and society's disenfranchised. A black woman poet in attendance writes,

in formal verse, about racism. An eclectic bunch, the participants at this

conference are united mostly in their conviction that modern poetry has become

boring, self-absorbed and unmemorable-one attendee describes it as "the avant-garde

of 1912." It's a trend they'd like to reverse.

In his controversial

1992 book Can Poetry Matter? (which grew out of a 1991 Atlantic Monthly

essay of the same title), conference co-founder Dana Gioia wrote that "poets

and the common reader are no longer on speaking terms."

Gioia notes that

Louis Untermeyer's Modern American Poetry went into print five times

between 1942 and 1945; thanks to the power of general readers, who kept it

on bookstore shelves. The only modern equivalent is the Norton Anthology,

which is targeted for university sales. Gioia and others decry the loss of

this general audience-the people who "buy classical and jazz records; who

attend foreign films, serious theater, opera, symphony, and dance; who read

quality fiction and biographies; who listen to public radio and subscribe

to the best journals," as Gioia puts it. Where did they all go? In part, they

were driven away, he argues, by a surfeit of flat-footed prose broken into

lines to look like "poems"-and telling us entirely too much about the self-involved

authors' lives.

One way poets

could re-engage modern readers, Gioia and others believe, is by returning

to and reclaiming the old devices of rhyme and meter and recognizable forms-the

tools by which poets once sought to delight the ear as well as the mind. That's

why we can all recite Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven"-and even Edward Lear's

"The Owl and the Pussy-Cat"-and not the greatly hailed poems of the past decades.

(How many among us can recite even a line of John Ashbery or Adrienne Rich,

two of the most heavily awarded, widely published poets of the latter 20th

century?)

The response

was electric. Gioia's piece generated more mail than the Atlantic Monthly

had ever received. Its editors, Gioia wrote in a follow-up article, "had warned

me to expect angry letters from interested parties. When the hate mail arrived,

typed on letterheads of various university writing programs, no one was surprised."

Articles attacking and defending the piece were published in the Times

Literary Supplement, the New Criterion, USA Today and the

Washington Post, among others. The big surprise was the groundswell

of enthusiastic public support. "Reporters phoned at the office for interviews,"

Gioia wrote. "Friends phoned with anecdotes about the article's impact. Strangers

called to ask advice. And for months the mail continued."

Gioia knew he

was onto something. And he knew a bit about the general audience he wanted

to attract, having been a vice president of marketing at General Foods, writing

poetry on the side, before leaving the business world for a full-time career

as a man of letters. Now he was in the business of marketing an idea. And

through his friendship with an idiosyncratic English professor at tiny, obscure

West Chester University-hardly a titan of the liberal arts-the ideas expressed

in the book took on a different kind of reality.

I 'm a reader,

I'm not a poet," admits Michael Peich, who decided to found the conference

with friend Dana Gioia late one night after a bottle of wine. "My few feeble

attempts at poetry resulted in disaster."

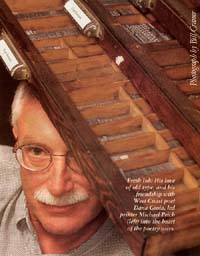

But as a printer

of poetry, the 56-year-old Peich is top-of-the-line. Adjacent to the fifth-floor

stacks at West Chester's Francis Harvey Green Library are the offices of Aralia

Press, an award-winning fine press he established in 1983. Here Peich creates

his labor-intensive books, setting type by hand, letter by letter. The room

is crowded with drawers and drawers of old-fashioned typefaces-for example,

one called RomanČe, from 1920s Holland. "An absolutely gorgeous type; very

little made its way into this country," says Peich enthusiastically. "I bought

it at a bargain-basement price-but it's priceless. When it wears down, that's

it." Nearby sit a double-dolphin "nipping press" from the late 19th century

and the Vandercook "proofing press" from the 1960s, salvaged by Peich, that

performs most of Aralia's day labor.

Peich and his

wife, Dianne, were inspired by Virginia and Leonard Woolf's home-based Hogarth

Press, which published new and experimental work from a range of outstanding

authors including T.S. Eliot, Rainer Maria Rilke and Katherine Mansfield.

Peich's longstanding

love of book-collecting and fine presses had led him to interview K.K. Merker,

one of the preeminent fine-press printers of our time, who told him, "If I

can make books, you can make books." Peich began an apprenticeship with John

Anderson in Maple Shade, New Jersey. Anderson was a highly skilled and regarded

craftsman, but he had two habits that appalled the meticulous Peich: He was

a chain-smoker, and he loved bourbon. Peich managed to swallow the bourbon

to please his master, but he resisted the cigarettes.

The magic of

creating the printed page took strong hold: "I will never forget the first

moment I pulled a sheet from the press," says Peich. Since then, he has achieved

distinction in a very rarefied field. In 1996, Aralia received an award from

the American Institute of Graphic Arts for book design for Poems for the

New Century, a book of up-and-coming poets produced in conjunction with

the New York Public Library. Laid in a silk-covered clamshell box, the 48-page

book costs $100.

While a few other

universities offer classes "book arts" at the graduate level, West Chester,

thanks to Peich and Aralia, gives undergrads the opportunity to set metal

type by hand, design pages, print single sheets on a hand press and do simple

book-binding. Aralia's published titles have included works by Richard Wilbur,

Anthony Hecht, Rita Dove and Philip Levine, as well as by famous names from

the past, like G.B. Shaw and Paul Valery.

At the same time

he was launching Aralia Press, Peich was discovering his passion for poetry.

But much of what was being written was no longer speaking to him. "I was tired

of reading Ginsberg and Denise Levertov-I started going back to Robert Frost,"

says Peich. (Frost, you may recall, famously compared free verse to "playing

tennis without the net.") "I started going back to very basic formal structures.

I had been right out there with confessional and lyric free verse. It began

to bore me, frankly. I was looking for something different. I began to ask,

'Is anyone writing in form today?'"

Then came a phone

call out of the blue. Dana Gioia had been tipped off by a book dealer that

Peich was interested in the neglected poet Weldon Kees, whose work Gioia was

collecting and editing. The synergy was immediate; they talked for two hours.

"If we were doing a buddy movie, I would be Mel Gibson, he would be Danny

Glover," says Gioia.

Gioia, 49, is

of medium height and wiry, with a voice that carries like an actor's. Peich,

tall and stately, with silver hair, contains his enthusiasm. While Peich is

thoughtful and diplomatic, Gioia is boundlessly energetic and self-confident,

a one-man dynamo who tends to pull people into his wake-but "I don't cow Mike,"

Gioia says. "Mike and I work as equals."

Gioia became

Aralia Press's unofficial literary editor. Following the example of the ČmigrČ

publishers of Paris in the 1920s, such as Sylvia Beach-who published James

Joyce's Ulysses-Peich was able to satisfy his ambition to publish writers

"who deserved and needed an audience."

Gioia and Peich

came up with the idea for the West Chester conference one night over a bottle

of Sonoma wine. They wanted to forge a third path for poetry, one that ran

between the dry excesses of academic literary analysis and the raucous, flashy

poetry slams that were becoming increasingly popular. They had no inkling

of what lay ahead. As Gioia has put it, "Any idea sounds more plausible after

a bottle of pinot noir." A few days later, they received some advice from

a friend with experience in similar ventures: "Don't do it. You have no budget,

no staff, no lead time."

With only seven

months to pull it together, they forged ahead. The first conference, in 1995,

ran on a shoestring, with eminent faculty working as unpaid volunteers. The

gap the conference was trying to fill is obvious. "Although there were over

2,000 writing conferences in the United States," says Gioia, "there was not

one where a young poet could learn the traditional craft-meter, rhyme, stanza,

fixed forms and narrative. Formal technique is wonderful, but you can't do

it half-assed. It helps to have some training -just like music."

This year, West

Chester has announced that it plans to raise $1.65 million for an endowment

to support the conference and Aralia Press. "West Chester was properly suspicious

of us at first," says Gioia. "But now that they have seen that the conference

is the most influential, intellectual event the university has ever hosted,

they have announced that they will raise the funds to support us. The first

six years, Mike and I kept the conference running without any institutional

support whatsoever."

You'd hardly

know it. This past June, the halls of Sykes Union buzzed with poets rushing

to and from private conferences and seminars on blank verse, stanza and pattern,

and poetic line. While some attendees are fledgling writers, others have a

few books behind them but feel their craft is lacking. Great things have started

at small, off-the-beaten track colleges in the past. The Black Mountain Poets

of the 1950s, for example, were associated with Black Mountain College in

Asheville, North Carolina.

In London, where

free verse never had quite the death-grip it has enjoyed in the land of Whitman,

the Times Literary Supplement wrote approvingly in Spetember 1999,

"America may be the enterprise culture sans pareil, but it manifested

its literary side in West Chester in a spirit of collaboration, honoring mentors

and fostering the talents of its diverse participants."

Beyond the leafy

1960s-era West Chester campus, however, the debate rages. Much of America's

mainstream poetry world hasn't bought the "New Formalism" despite a decade

of hard selling. Philadelphia's own Stephen Berg, who founded the American

Poetry Review 28 years ago, professes to know little of the large gathering

taking place a mere 25 miles away-even though one of his assistant editors

is on the West Chester faculty and serves as an administrator for the event.

"I don't know

what the New Formalist movement is-nobody knows what it is. It's just a name,"

he says brusquely.

("Now you know

what we've been putting up with for years," Gioia tells me later.)

The "Reaganites"

label has had legs, but it's a charge that doesn't stick. For one thing, the

New Formalists aren't all that formal; one has suggested renaming the movement

the "Few Normalists." And calling metrical poets "Reaganites" is akin to claiming

that ballet dancers must be right-wing and modern dancers left-wing -or that

performers of Mozart are all conservatives, while Stockhausen fans are all

liberals.

The New Formalists

at West Chester may have already won the bigger war. Free verse is no longer

the unshakeable orthodoxy it once was; the invincible wall has been cracked.

One indicator is a renewed national interest in the art of versification -the

past six years have seen an avalanche of prosody handbooks, and a healthy

crop of blank verse, villanelles and rhymed quatrains. Mainstream poetry journals-including

Poetry, the most prestigious such publication in the nation-regularly

run works in formal meter, which many considered unthinkable two decades ago.

So in a sense, Berg is right: While many poets know little about the movement,

they are now experimenting with form, and writing within it. It's akin to

a familiar political situation: While many women reject the "feminist" label,

they still want equal pay and subsidized day care.

Addonizio herself

has reservations about the "formalist" label: "I guess I'm happy to be considered

one if it gets my work out there to people," she says. "But I really consider

myself a poet. I don't want to be ghettoized. Identity politics is useful-but

ultimately, you want to move beyond it."

Even Ira Sadoff,

who published his angry screed in the American Poetry Review all those

years ago, seems ready to admit defeat: He now describes himself as "one poet

among a decreasing minority who is trying to resist the return to formalism,

the sterile, conservative, aesthete academicism of the 1950s."

Gioia, as usual,

loves a fight: "It doesn't surprise me that an older poet like Sadoff is less

interested in form than younger poets, who seem to be quite excited by it,"

he snips. "He doesn't realize that he is on the far side of a new generation

gap. Is rap an extension of formal academic poetry of the 1950s because it

uses rhyme and meter? It's a silly argument."

Regardless of

the sniping, this year's opening banquet is attended by more people than attended

the first few. And the audience in Sykes Auditorium is oblivious to charges

that they are turning back the clock. They listen as Addonizio croons her

haunting lyrics about drinking, tough neighborhoods and lost love. She reads

the rest of her sonnet into the microphone:

Now I get

to feel his hands again, the kiss

that didn't last,

but sent some neural twin

flashing wildly

through the cortex. Love's

merciless, the

way it travels in

and keeps emitting

light. Beside the stove

we ate an orange.

And there were purple flowers

on the table.

And we still had hours.

Cynthia Haven

is a literary critic for the San Francisco Chronicle and has written

for the Washington Post, Civilization, and the Los Angeles

Times Book Review. E-mail: mail@phillymag.com

Reprinted

from Philadelphia, November, 2000.

Photograph

by Bill Cramer

|