|

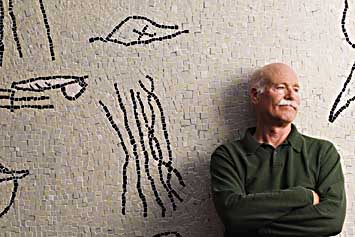

WOLFF: ’You imagine who

you are.’

Glenn Matsumura |

When author Tobias Wolff’s

latest book, Old School, came out last winter,

it was trumpeted as the author’s first novel.

Many asked the obvious question: Why, suddenly, a novel?

Wolff, MA ’78, a professor in Stanford’s

creative writing program, has long been known as a passionate

advocate for the short story form. He has published

three books of his own stories and edited several other

collections. He called the short story “the perfect

American form” in a 1996 Salon interview,

saying “most of us don’t live lives that

lend themselves to novelistic expression, because our

lives are so fragmented. Instead of that long arc of

experience, that sustained community that’s implied

by a novel, there are these moments.”

Wolff is a fast talker, and words don’t fail

him on this occasion. “I don’t write short

stories out of any slavish devotion to that form,”

he tells me, but rather “because the story I have

to tell will work best in [it].”

His answer isn’t entirely convincing. But then

again, it turns out that Old School is not

really his first novel. His publisher, Knopf, had already

printed the dust jackets when the author remembered

it wasn’t. His first novel, Ugly Rumours,

was published in England in 1975. Wolff told the Los

Angeles Times that he leaves the book off his list

of published works because “within two or three

years of having written it, I couldn’t read a

word of it without cringing. So I don’t call attention

to it.”

Now you see it; now you don’t. That seems typical

of Wolff the literary magician, Wolff the inventor,

a man who extols the force of imagination in shaping

destiny. “You can’t become what you can’t

imagine becoming,” he says. “You imagine

who you are. Your life forms itself towards that notion.”

Wolff has a certain forza del destino about

him: he’s strikingly tall and muscular. His gaze

is sharp and direct and he is largely bald, lending

an impression of boldness. He’s a former Vietnam

Green Beret officer, with “command presence,”

as he explains in his 1994 memoir, In Pharaoh’s

Army. He’s also a vegetarian. He’s

a man of apparent contradictions. A lifelong academic

thrown out of prep school for bad grades. A family man

(with three children) who came from one of the most

mixed-up, broken homes imaginable.

Perhaps his most revealing comments come when the subject

turns to Robert Frost’s famous poem “The

Road Not Taken” and its conclusion, “I took

the one less traveled by,/And that has made all the

difference.” The poem is commonly taken in a “Hallmark-card

way, as inspirational verse,” Wolff says. Yet

the poet remarks that the two paths are both “just

as fair” and “worn . . . really about the

same.” Wolff says the key lines are “I shall

be telling this with a sigh/Somewhere ages and ages

hence.” The narrator is already imagining himself

as an old gaffer, telling the youngsters what made him

great. For Wolff, it’s the story of how we invent

ourselves and the stories we will tell in the future.

“Things don’t happen to us in stories.

We make the story. The very act of remembering

is bending experience,” he says. “You do

it unwittingly. The faculty of your memory is doing

this even before you get to it.”

It’s typical of Frost, Wolff adds, to write a

poem that was so greatly misread. “He was a very

double guy. He didn’t like being known. He didn’t

like people to have his number.” One wonders if

the same might be said of Wolff—a self-invented

man, a cat landing on his feet.

“There’s nothing inevitable at all in the

luck I’ve had,” he admits. That includes

a six-month stint as a Washington Post reporter.

He landed the job shortly before Watergate, when he

met executive editor Ben Bradlee at a party and asked

for a job. He was hired over many applicants with journalism

degrees from top universities. Why? Bradlee later confessed

to him, “Because you called me ‘sir.’”

“I wasn’t a good reporter. I didn’t

have any future as a reporter, and didn’t really

want one,” Wolff says. “I wanted to write

fiction.”

His career was launched in 1976 when Atlantic Monthly

pulled from a slush pile the short story he wrote while

a Stegner Fellow. “It was a great break,”

he concedes. “But it could just as easily have

happened that [fiction editor] Michael Curtis passed

over that story, or that he was in a bad mood that day,

or that somebody else at the magazine didn’t like

it.”

|

|

“Things don’t

happen to us in stories. We make the

story."

- Tobias Wolff |

Wolff was hardly a child prodigy. “Think of it

this way,” he says. “When I was 30, my contemporaries

were in big apartments, getting their first Volvos.

Meanwhile, I’m popping champagne over a story

in the Atlantic Monthly for which I’m

paid $500.”

Leaving his office, we walk briskly across the Quad

to a seminar course he’s guest teaching. Wolff’s

strides are long and fast, and it’s hard to keep

up as he heads towards a basement classroom.

The students are studying The Divine Comedy.

On the way to class, Wolff expresses some concerns—Dante

is not his field—but once he is before the two

dozen students, his comments are characteristically

sharp and provocative. When asked if Dante is the hero

of the commedia, Wolff distinguishes between a pilgrim

and a hero.

“The treasure he is after is the redemption of

his soul. He makes it so actual for himself that he

actually underwent it.” Wolff has returned to

the perennial theme of a man creating his fate. He tells

the class the “self-inventing man” is the

central motif of American literature.

Inventing his own identity came early to Wolff, who

grew up in a small town near Seattle. His mother is

100 percent Irish; his father 100 percent Jewish—though

Wolff didn’t learn about his Jewish heritage until

adulthood. He describes his father as an engaging, charming,

compulsive liar.

Like father, like son. As a boy, Wolff had a similar

habit of making things up. According to his 1989 memoir

This Boy’s Life—made into a 1993

film starring Robert De Niro, Ellen Barkin and Leonardo

DiCaprio—he was always telling whoppers, always

faking it in a bizarre, ruffian childhood. He had an

absentee father, a beautiful, footloose mother, and

a rough-cut stepfather.

Wolff wrote so tirelessly as a kid that he gave his

stories to friends to submit for extra credit in school.

In typical fashion, he faked his own transcript and

letter of recommendation to get into the tony Hill School

in Pottstown, Penn. As he recounts the experience in

This Boy’s Life:

Now the words came as easily as if someone were

breathing them into my ear. I felt full of things that

had to be said, full of stifled truth. That was what

I thought I was writing—the truth. It was truth

known only to me, but I believed in it more than I believed

the facts arrayed against it . . . And on the boy who

lived in [the] letters, the splendid phantom who carried

all my hopes, it seemed to me I saw, at last, my own

face.

On the basis of his self-recommendations, he was accepted.

The story is kindred to his new novel.

On the cover of Old School, a hundred or so

young men, in jackets and ties dating from the early

’60s, line immaculate tables formally set with

white tablecloths. Their heads are bowed, presumably

for some sort of blessing, under the chandeliers.

Wolff could be somewhere among them, for the photo

is of the Hill School. In the book, imagination blends

with autobiography as seamlessly as the real-life school

on the cover of a piece of fiction. The novel tells

of a young man in an East Coast prep school that encourages

aspiring writers by sponsoring a writers’ competition

each year. The winner spends time with a famous writer

visiting campus—Robert Frost among them.

Its most haunting theme is the way lying—whether

by omission, misleading remarks or outright fraud—underpins

our lives. Nothing is what it seems. Each student’s

work is misunderstood by the famous writer who judges

it. People lie without even realizing they are lying,

and the momentary failure to correct a misunderstanding

creates legends that are impossible to refute years

later. The book culminates with an act of plagiarism.

Wolff’s story parallels his hero’s; however,

no climactic lie caused Wolff’s departure from

Hill. The cause was more pedestrian: Wolff was asked

to leave in his final year because his grades were so

poor. As he writes in This Boy’s Life:

“I did not do well at Hill. How could I?

I knew nothing. My ignorance was so profound that entire

class periods would pass without my understanding anything

that was said.... It scared me to do so poorly when

so much was expected, and to cover my fear I became

one of the school wildmen—a drinker, a smoker,

a make-out artist at the mixers we had.... While the

boys around me nodded off during chapel I prayed like

a Moslem, prayed that I would somehow pull myself up

again so I could stay in this place that I secretly

and deeply loved.

A strange beginning indeed for a Stanford professor,

but one in keeping with his message that there is more

to life than nature versus nurture. Wolff insists we’ve

overlooked the role of individual will and imagination

in forging an identity. He ought to know. |