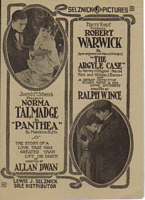

Panthea (1917) Norma Talmadge Film Corporation/Selznick Pictures. Presented by Joseph M. Schenck. Directed by Alan Dwan. Camera by Roy Overbaugh. Gowns by Lucile. Cast: Norma Talmadge, Earle Foxe, Roger Lytton, George Fawcett, Murdoch McQuarrie, Erich von Stroheim, Norbert Wicki, William Abington, Winifred Harris, Eileen Persey, Stafford Windsor, Dick Rosson, Frank Currier. 5 reels.

This lost film was Norma Talmadge's first independent production with Joseph M. Schenck, and was distributed by Louis Selznick. The play had been a hit for Olga Petrova, and though considerably sanitized for the screen, it was a huge success for Talmadge. This was her second and last film with director Allan Dwan. It was produced in late 1916, released in January of 1917, and later re-released in 1920. Talmadge and Schenck were married during the production of the film, an incident described by Dwan to Peter Bogdonovich in his book Allan Dwan, the Last Pioneer (New York: Praeger, 1971). This film apparently showed in 1958 in Venice, so perhaps a print may still turn up.

|

An advertisement for the film (thanks to Derek Boothroyd for this) |

| Panthea Romoff | Norma Talmadge |

| Baron de Duisitor | Roger Lytton |

| Prefect of Police | George Fawcett |

| Gerard Mordaunt | Earl Fox |

| Secret Agent | Murdock McQuarrie |

| Liutenant of Police | Count E. Von Stroheim |

| Ivan Romoff | Norbert Wicki |

| Sir Henry Mordaunt | William Abbington |

| Gerard's mother | Winifrid Harris |

| His sister | Ieleen [i.e. Eileen] Peisey |

| Percival | Stafford Windsor |

| Pablo Centeno | Dick Rosson |

| Dr. Von Reichstadt | Frank Currier |

"Panthea," the Norma Talmadge (Selznick) screen adaptation of the Monckton Hoffe play of that name, held the unique distinction of being probably the first feature production to be simultaneously shown at the Rialto and New York theatres (within a stone's throw of each other) early this week. Had it failed to live up to its promise there would have been much weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth in the vicinity of Times Square. But the contrary was the case, for both huge houses apparently played to overflowing audiences. Too much praise cannot be bestowed upon Allan Dwan, director, and Roy Overbaugh, cameraman, not to mention the star and the entire acting organization. As a production it is almost too realistic in the first part, which is a sort of prolog to what was originally the legitimate presentation. It visualizes the horrors of Russian nihilism with most agonizing details. The screen version of "Panthea" has been materially edited and is therefore more wholesome for general motion picture assimilation. For instance Gerald Mordaunt is a single man when Panthea elopes with him, instead of having abandoned a wife, and throughout Panthea remains a good woman, always pure in spirit and only sacrificing herself to the baron the secure a production of her husband's opera. A happy ending is also provided, showing the couple seated by a camp fire en route to Sibera [sic] with husband promising that her release will soon be secured through the powerful influence of her father-in-law. Panthea's sacrifice on the altar of love is admirably portrayed by Miss Talmadge, and her sweet, animated countenance was never utilized to greater advantage before the camera. Earle Fox as the leading man and Roger Lytton as the "heavy," were strong contenders with Miss Talmadge for stellar honors, which shows the good judgment displayed by the sponsors of the first Talmadge special release in surrounding her with the best available support. The atmosphere and scenic and costume details were on a par with the intelligent handling of the remainder of the production. If future Talmadge special releases are of equal calibre as "Panthea," Miss Talmadge is certain to remain in the front rank of sensational drawing cards.

A screen version of Monckton Hoffe's drama "Panthea" was shown in both the Rialto and New York Theatres. Norma Talmadge acted the title role created by Olga Petrova when the drama was acted at the Booth several seasons ago. Curiously enough, the best part of the film is the preliminary portion in which are outlined the events preceding the episodes that made up the action of the play. Through clever staging and lighting, the director managed to get considerable atmosphere into the Russian scenes and that of the shipwreck. An excellent cast that included George Fawcett in a wicked black mustache acted for the film.

The Shadow Stage: A department of Photoplay Review

by Julian Johnson

... [omitted reviews of several other films]

PANTHEA. Here is another screen novel: directly told, staged with an eye both to artistic lighting and dramatic effect, true to life even in its most melodramatic moments, tingling with suspense, saturate with sympathy. All of which sound as though we considered it the best picture of the month. We do. It is one of the best photoplays in screen history, and if there were more like it every interpretive art would have to cinch its figurative belt and prepare to fight for existence.

All of this notwithstanding a watery and ineffective ending; where both author and director seem to fatally hesitate between marshmallows and catastrophe, and, having a mind to neither, uncomfortably straddle a problem picket fence.

"Panthea" first served the serpentine Petrova, when the Schuberts introduced her as their tragedy white hope. At this time it was an alleged transcript of turgid life, and considerable sapolio might have been used in its sordid corners. Here, with the exception of the wavering finale, it is all quite antiseptic--there are deep thrusts and wide wounds, but they are made with clean swords.

Panthea herself is a piano graduate of the Moscow conservatory. At her keyboard valedictory a number of impresarii attend, amond them a Baron. The Baron sizes up Panthea's person rather than her performance, and connives with his friend, the Moscow Chief of Police, to have Panthea raided on a charge of Nihilism. Then he--the Baron--may demand and secure her release, thus establishing himself forever in her good graces. But it happens that Panthea's brother--presented by his parents with the not uncommon name, Ivan--is really a Nihilist, and is holding vigorous revival services of his own kind when the fixed police arrive to arrest Panthea. The sham turns into reality. Ivan flees, and a soldier is killed. Now the Baron will have to extend himself indeed--but Panthea, helped out of a vaulty prison by a common soldier who had once been her schoolmade, escapes to England. She is pursued by a secred police agent, on the same boat. There is a wreck off the English coast, and Panthea, unconscious, is carried to the Mordaunt estate. Gerald, the piano-playing younger son, immediately discovers a soul-and-music affinity, and they trip off to Paris, where they live in happy married life for a year. Gerald would be an Anglo-Saxon Verdi, and wilts daily because he cannot get his opera produced. Panthea goes to a French manager who is about to turn her down when a distinguished visitor from Russia sees her card. It is no great surprise to learn that it is our old friend the Baron. Panthea is in the toils again. She makes the compact to save her husband's life, while the Baron, Scarpialike, arranges to have her pinched as soon as his personal purpose is accomplished. But a weak heart gets him in her parlor, and he does not long outlive his culminary villainy. The police agent is on hand and starts back to Russia with her. The final fadeout is upon her and Gerald, camping in the Siberian snow, while he assures her that the English diplomatic machinery must even now be grinding the grist of their formal release.

The direction is Allan Dwan's, and he manifests that same leisurely, perfect passion for detail that he showed in "Betty of Greystone." The lieutenant who comes to arrest Panthea in the early episodes is the perfect picture of the "well, it's all in the day's work" type of blase young militarist. Wonderful is the revelatory close-up when the Baron attends Panthea's recital: all the other old men, we infer, are watching her hands, for there is a great keyboard closeup: but when it is the Baron's turn we get a close-up of Panthea's shapely foot and promising ankle, upon the pedal! Equally subtle is the first view of the Baron in the Parisian office; he is in a deep chair, back to us, and only his eager hand, reaching for Panthea's card, is visible--but we know that it is he.

The lighting of this play sets a new mark in photodramatic illumination. The tone in the main is deep, as it is with most of Dwan's plays, but it is never gloomy.

Norma Talmadge plays Panthea with a verve, abandon and surety which denominates her queen of our younger silver-sheet emotionalists. There is no woman on the depthless stage who can flash from woe to laughter and back again with the certainty of this particular Talmadge. She is 100 percent surefire. Rogers Lytton, as the Baron, surpasses all his other efforts. Earle Foxe plays Gerald in psychopathic correctness. George Fawcett is totally disguised as the sinister Chief of Police; Murdock MacQuarrie comes to the fore with all his fine old melodramatic resource as the Secret Agent, and the rest of the faultless cast includes such players as William Abingdon and Winifred Harris.

There are several points where the plot wears perilously thin, but the craft of the director and the artifices of the players send the beholder skating safely across.

... [omitted reviews of several other films]

|

Another picture from Panthea from the same issue of Photoplay in an article about L. Rogers Lytton. |

PANTHEA (Five Parts--December.--The cast includes Norma Talmadge, Roger Lytton, George Fawcett, Earle Fox, Murdock McQuarrie, Count E. Von Stroheim, Norbert Wicki, Herbert Barry, Jack Meredith, Henry Thorpe, William Abbington, Winifred Harris, Ieleen Pelsey, Stafford Windsor, William Lloyd, Dick Rosson, Frank Currier and J.S. Furey. Directed by Allan Dwan

Panthea, a Russian musician suspected of revolutionary activities, escapes the surveillance of the secret police and goes to England. She meets, loves, and marries a young English composer, whose ambition is to have one of his operas produced. The couple move to Paris, where Panthea meets a Russian nobleman who knew her in her mother country and who has a powerful influence in musical circles. Panthea's husband becomes desperately ill through the failure to secure a hearing for his opera and the physicians express their belief that unless the boy's ambition is speedily realized there can be no cure.

Panthea urges the Russian baron to produce the opera. Driven to desperation to save her husband she accepts the baron's full-blooded proposal and sacrifices herself. The opera is produced with triumphant success. Her husband discovers the sacrifice that Panthea made for his sake and at first turns from her in loathing. Panthea, in despair, kills the baron, who has failed to live up to his end of the agreement. The story ends with Panthea and her husband reunited and bound for exile to Siberia.

Appearing in "The Movies Are": Carl Sandburg's Film Reviews and Essays, 1920-1928, edited by Arnie Bernstein (courtesy of the publisher)

In Panthea Norma Talmadge gives an exhibition of passion at times truly Nazimovesque. Panthea is the story of a woman’s sacrifice for the man she loves. The unfolding of its sensational plot holds the attention of the audience focused on the absorbing acting of this brilliant star of the movies. Panthea is a young Russian girl whose beauty and talents attract an unscrupulous baron. With the chief of police this baron arranges to have Panthea arrested on a trumped up charge, whereupon the baron is to rush to her rescue and place the beautiful girl under the weighty obligation of lasting gratitude for saving her from the horrors of a Russian prison. But a former lover spoils the baron’s plans by helping her escape from the prison before the baron can stage his rescue act. Off the English coast the steamer catches fire and Panthea reaches shore to find her temporary refuge in the home of an English nobleman whose estate borders the beach. A son of the nobleman falls in love with Panthea and elopes to Paris with the handsome Russian girl. There the husband composes an opera of merit, but grows sick with despondency over his failure to find a producer who will put his masterpiece on the stage. In this crucial moment when the happiness of Panthea and her temperamental husband hangs upon a successful presentation of his cherished opera the Russian baron reappears and tells Panthea he will put her husband’s opera on the stage if she will sacrifice herself to him. The Russian’s girl’s adoration for the poor, weak man she has married leads her to consent to the baron’s proposal. The opera makes its initial bow with startling success. Panthea’s husband discovers the relations between his wife and the baron. The baron drops dead from an attack of heart disease, while Panthea is rewarded for her sacrifice by her husband’s tardy understanding of her anguish.

More information on this film can be found in the following source:

Magill, Frank N., ed., Magills Survey of Cinema: Silent Films. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Salem Press, c1982 (entry on Panthea by DeWitt Bodeen).

Last revised, December 22, 2008