Scaling up multimodal models has enabled remarkable advances in visual understanding and reasoning, but practical demands call for smaller, efficient systems.

However, the consequences of downscaling intelligence remain poorly understood. Namely, when a smaller language model serves as the backbone,

which capabilities degrade the most, and why?

In this work, we perform a systematic investigation of downscaling intelligence in multimodal models through three main aspects:

Figure 1. Click to jump to each section👆.

In the first part of this work, we conduct a controlled study to examine how reducing language model size impacts multimodal task performance, aiming to understand the limitations of small models as general visual assistants and the causes of their failures. We present our findings below:

Figure 2. LLM downscaling exploration. (Left) Performance dropoff from LLM downscaling most notable for visually demanding tasks. Tasks like Grounding and Perceptual Similarity (e.g., NIGHTS and PieAPP) which primarily focus on visual processing are most affected by LLM downscaling, rather than tasks which rely heavily on the base LLM (such as ScienceQA evaluating knowledge or GQA assessing general abilities). (Right) The more a task's performance declines under LLM downscaling, the greater it depends on visual information. As the impact of LLM downscaling increases (8B $\rightarrow$ 0.6B), so does the task’s reliance on visual information (measured by performance difference with and without visual input).

Tasks with largest performance drops under LLM downscaling rely heavily on visual processing, not the base LLM. As shown in Figure 2(Left), most tasks exhibit modest performance decline when downscaling the language model size from 8B to 0.6B, except for a few tasks which exhibit much larger deterioration. Interestingly, rather than these tasks depending heavily on the base LLM (such as ScienceQA, which assesses knowledge, or GQA, which evaluates general abilities), they instead rely primarily on visual processing. For example, Grounding drops 48% and NIGHTS (Perceptual Similarity) declines 38% when downscaling from 8B to 0.6B.

The greater the impact of LLM downscaling, the more the task relies on visual information to be solved. While our analysis so far has focused on the few tasks most affected by model downscaling, here we extend the analysis to the full set of datasets. To better understand how a dataset’s sensitivity to LLM downscaling relates to how vision-centric the task is, we plot the performance difference between the 8B and 0.6B LLMs against the difference in performance with and without visual input (using the 8B LLM). As shown in Figure 2(Right), most datasets exhibit an approximately linear trend: as the impact of LLM downscaling increases, so does the task’s reliance on visual information. The exception is ImageNet, where the small model achieves very strong performance but blind performance is near zero. This likely occurs because the perception required is notably simple and the task comprises a large portion of the visual instruction tuning data.

Takeaway 1: LLM downscaling is most detrimental to vision-centric capabilities rather than base LLM abilities.

Our findings in the previous section are intriguing, but the reason behind the observed trend remains unclear. Namely, vision-centric tasks generally require two essential capabilities: perception, the foundational ability to recognize, extract, and understand visual details, and reasoning, the downstream ability to operate on extracted visual information to formulate answers. While our analysis showed that the visual capabilities of multimodal models degrade significantly under LLM downscaling, it did not reveal the mechanisms underlying these failures. Given that reasoning depends on model scale for textual tasks, we expect visual reasoning to decline under downscaling; however, the effect on the more foundational process of perception is highly uncertain and warrants further study. Thus, in this section, we perform a rigorous analysis separating the effects of LLM downscaling on perception and reasoning to better understand the causes of the observed behavior. We present our findings below:

Figure 3. Decoupled perception and reasoning downscaling analysis. (a) Decoupled Setup. We disentangle perceptual and reasoning abilities using a two-stage framework: the perception module (VLM) first extracts visually relevant information, then the reasoning module (LLM) generates answers based on the extracted visual information. (b) Perception and reasoning emerge as key bottlenecks under LLM downscaling. We see that LLM downscaling of either the perception module or reasoning module largely degrades in-domain and out-of-domain task performance. (c) Perceptual degradation limits performance across tasks. Even for tasks targeting visual reasoning (e.g., IR and LR), downscaling perception has an impact comparable to—or even exceeding—that of downscaling reasoning.

LLM downscaling expectedly hinders visual reasoning. As shown in Figure 3(b), we find that downscaling the reasoning module size has a considerable impact on performance across tasks, confirming that visual reasoning is a critical bottleneck for small multimodal models.

LLM downscaling markedly impairs perceptual abilities, affecting a wide spectrum of tasks. More notably, in Figure 3(b) we also observe that LLM downscaling of the perception module has as substantial an effect on performance, where downscaling from 8B to 0.6B causes an average accuracy drop of 0.15 for in-domain data and 0.07 for out-of-domain data. As shown in Figure 3(c), even for tasks that target visual reasoning (such as Instance Reasoning and Logical Reasoning), downscaling the perception module has an impact on performance comparable to, or even exceeding, that of downscaling the reasoning module. This likely occurs because the foundational ability to understand visual information is a prerequisite for successfully performing downstream reasoning.

Takeaway 2: While LLM downscaling expectedly impairs visual reasoning, isolating its impact solely on perception still reveals severe performance degradation across a wide range of tasks, often matching or exceeding its effect on reasoning.

Discussion. This section highlights an important and previously undiscovered phenomenon. The original Prism work used a relatively small LLM for the perception module (e.g., InternLM2-1.8B and a much larger LLM for the reasoning module (LLaMA-3-70B and ChatGPT)), based on the assumption that perception is far less sensitive to LLM scale than reasoning. Although reasoning is naturally expected to degrade more than perception, we find that its impact on performance is surprisingly similar to that of perceptual abilities. Thus, perception (alongside reasoning) emerges as a central bottleneck in small multimodal models. Given that the visual representations are fixed across model setups, what drives this perceptual decline?

We hypothesize that this perception bottleneck arises from a fundamental limitation of the visual instruction tuning paradigm under LLM downscaling. Namely, visual instruction tuning exposes the model to various ways of recognizing, understanding, and extracting visual information. We posit that this variability requires the model to acquire diverse skills for interpreting instructions and extracting the relevant visual information. The Quantization Model of neural scaling laws offers a theoretical lens: model skills can be "quantized" into discrete chunks (quanta), and scaling laws limit the total number a model can effectively learn from the training data. Because visual instruction tuning requires the model to learn many skills to process visual information across diverse tasks, smaller models have weaker perceptual capabilities.

Hypothesis: LLM downscaling's effect on perception arises from the heterogeneity of how perception is learned under visual instruction tuning.

As part of the following section, we leverage this hypothesis to guide method advancements aimed at improving the perceptual abilities of small multimodal models.

Having shown that LLM downscaling weakens both foundational perception and downstream reasoning, we conclude by proposing solutions that address these limitations and move toward a high-performing generalist small multimodal model.

We first aim to alleviate the foundational perception bottleneck for small multimodal models. As previously discussed, we hypothesize that the perception bottleneck on small multimodal models arises from the model needing to acquire a diverse set of skills to extract relevant visual information across a wide range of tasks. Thus, a natural approach to improve performance in downscaled LLMs is to increase the homogeneity of how visual information is extracted. In this section, we first assess captioning as a baseline method to achieve this, and then propose a new training paradigm, visual extraction tuning, which demonstrates strong abilities in enhancing perception in small multimodal models.

Figure 4. Captioning alleviates perception bottleneck. Decoupled frameworks use an 8B reasoning module.

Captioning baseline. A simple way to unify perceptual skills for visual question answering is to train the perception module as a captioner. We therefore post-train the perception module on ALLaVA-4V, a 950K caption dataset. As shown in Figure 4, this approach mitigates the effect of LLM downscaling and even outperforms end-to-end baselines at smaller scales (0.6B, 1.7B). However, captioning introduces two key limitations. First, the two-stage framework is not merely captioning plus reasoning; the first stage should extract question-relevant visual details, which captioning does not teach. Second, visual instruction tuning often involves specialized, domain-specific data. Training solely on general captioning datasets limits domain-specific understanding, as the model is not taught to interpret specialized visual concepts present in those domains. Thus, an alternative approach is required to address these limitations.

| Perception Module | Size | In-domain | MMStar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Captioning | 0.6B | 77.6 | 40.4 |

| + Visual Extraction | 0.6B | 82.8 | 44.0 |

| Δ | +5.2 | +3.6 | |

| Captioning | 1.7B | 80.3 | 44.4 |

| + Visual Extraction | 1.7B | 84.4 | 49.0 |

| Δ | +4.1 | +4.6 |

Figure 5. Visual extraction tuning. (Left) Simple pipeline for generating visual extraction tuning data. Given a visual instruction tuning example, it is converted to a visual extraction task by prompting a VLM to describe fine-grained visual details relevant to the original question. (Right) Visual extraction tuning enhances perception. Post-training on visual extraction data improves both in-domain and out-of-domain (MMStar) performance.

Visual extraction tuning. Here, we propose visual extraction tuning as a solution to unify the perceptual abilities of the perception module while enabling it to extract question-relevant information and operate effectively across the diverse domains present in visual instruction tuning. Provided visual instruction data, we design a simple pipeline that transfers this data to the task of visual extraction, where the goal is to generate all visual information relevant to answering the instruction, aligning precisely with the role of the perception module in the two-stage framework. As shown in Figure 5(Left), given a visual instruction tuning example, we first convert the question–answer pair into a declarative statement by prompting a model. We then integrate this declarative statement into a prompt that asks the model to describe fine-grained visual details, with explicit emphasis on information relevant to the declarative statement. Finally, this instruction, together with the image, is provided to a model to generate the visual extraction response.

Results. As shown in Figure 5(Right), we find that additionally post-training under the visual extraction tuning paradigm offers large performance improvements over the captioning baseline on both in-domain data and the out-of-domain MMStar benchmark. Specifically, in-domain performance increases by 5.2 when the perception module uses a 0.6B LLM and by 4.1 when it uses a 1.7B LLM. On the MMStar benchmark, performance improves by 3.6 for the 0.6B LLM and by 4.6 for the 1.7B LLM.

Takeaway 3: Visual extraction tuning proves an effective and efficient solution for alleviating the perception bottleneck of small multimodal models.

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning is a widely studied method for improving LLM reasoning. In our two-stage framework, although the reasoning module is not trained on visual data, text serves as an interface connecting perception and reasoning. Therefore, we expect that encouraging step-by-step reasoning in the reasoning module will directly enhance visual reasoning without requiring training.

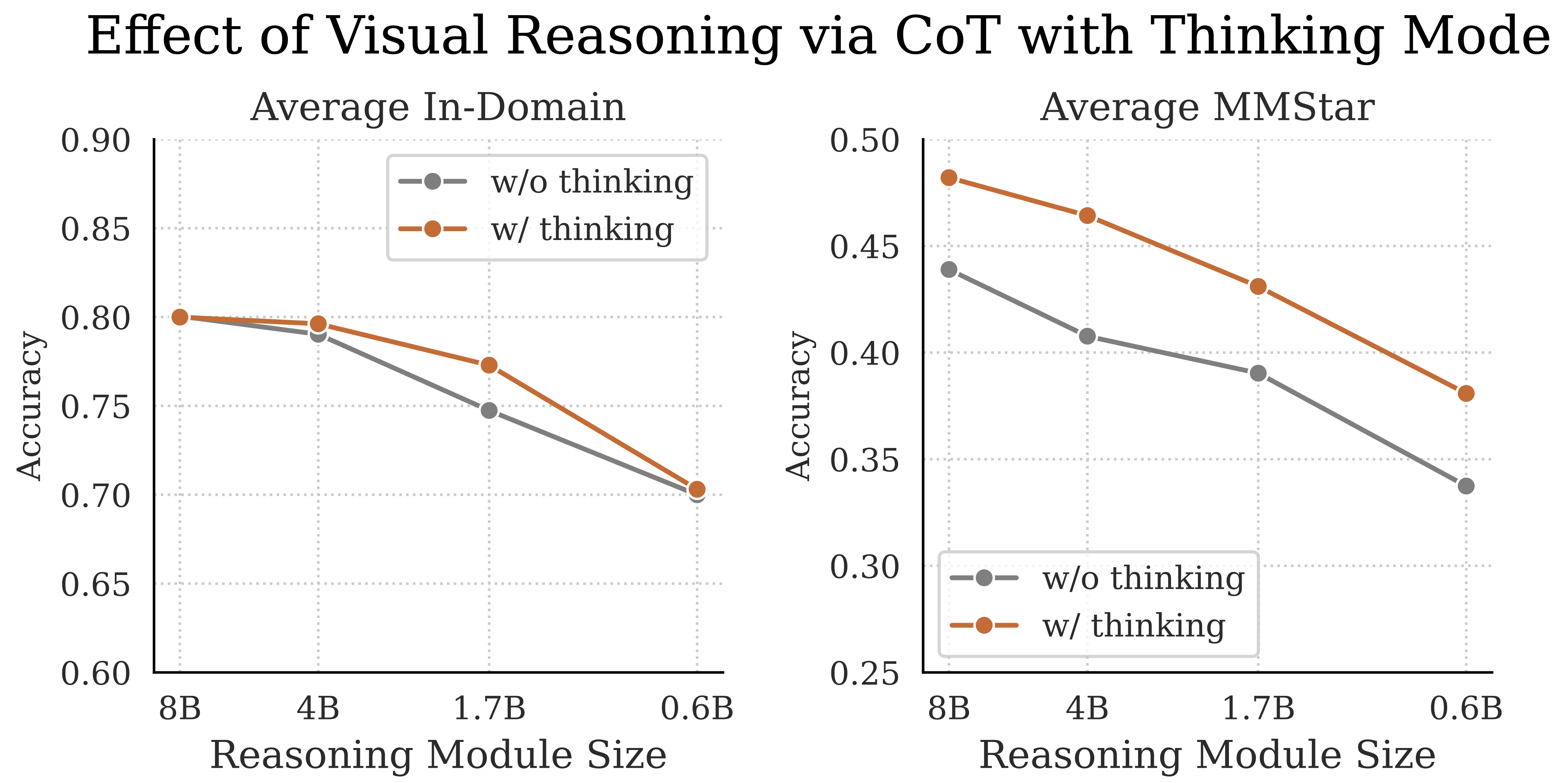

Figure 6. CoT reasoning enhances in-domain and out-of-domain performance. Performance gains exhibited at intermediate model scales (4B and 1.7B) for in-domain tasks, while out-of-domain performance improves across all LLM sizes. Both setups use 8B baseline perception module.

Approach. The Qwen3 model, which we utilize for the reasoning module, is capable of complex, multi-step reasoning by enabling thinking mode. Thus, we activate thinking mode and modify the prompt: instead of directly requesting the answer like before, we instruct the model to reason step-by-step. Since Qwen3 produces long reasoning chains, to improve efficiency we limit self-reflection with NoWait and limit the thinking budget to 4096 tokens.

Results. As shown in Figure 6, incorporating CoT reasoning substantially improves out-of-domain performance across all LLM sizes. For in-domain tasks, we observe a more nuanced behavior where the performance degradation under LLM downscaling becomes more concave when reasoning is enabled: the 8B and 0.6B models perform similarly with or without CoT, but at intermediate scales (4B and 1.7B), CoT yields notable gains. This suggests that while CoT does not fully resolve the reasoning bottleneck in smaller multimodal models, it meaningfully enhances performance--particularly at mid-range LLM sizes, where it brings results closer to those of larger models.

Takeaway 4: Utilizing CoT boosts visual reasoning capabilities without requiring any supervision on visual data.

Guided by these insights, we now present our final approach, Extract+Think. Specifically, we employ the perception module trained under our proposed visual extraction paradigm and a reasoning module enhanced with CoT reasoning. Based on our finding that CoT does not fully resolve the reasoning bottleneck in smaller multimodal models, we adopt a larger LLM for the reasoning module than for the perception module (while keeping both models within a lightweight regime). We compare against both end-to-end baselines and other decoupled methods, including PrismCaptioner, the original decoupled setup, and the captioning baseline (denoted Caption+Think). We present our results below.

| In-Domain (Multiple Choice) | Out-of-Domain (MMStar) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM Size | # Vis. Data | OCR-VQA |

TextVQA |

ScienceQA |

VQAv2 |

GQA |

VizWiz |

Average |

CP |

FP |

IR |

LR |

ST |

Math |

Average |

||

| End-to-End | |||||||||||||||||

| LLaVA-OneVision | 0.5B | 8.8M | 69.5 | 77.2 | 55.7 | 75.7 | 73.6 | 74.7 | 71.1 | 63.2 | 31.1 | 42.1 | 35.8 | 30.0 | 31.4 | 39.0 | |

| InternVL2.5 | 0.5B | 64M | 79.8 | 89.1 | 89.8 | 82.0 | 75.4 | 83.0 | 83.2 | 69.9 | 38.8 | 53.9 | 37.7 | 39.3 | 49.7 | 48.2 | |

| SmolVLM | 1.7B | unk. | 72.9 | 81.4 | 79.7 | 75.5 | 70.6 | 75.1 | 75.9 | 69.2 | 30.6 | 45.9 | 37.9 | 29.8 | 34.2 | 41.3 | |

| Our Baseline | 0.6B | 1.0M | 41.1 | 71.3 | 67.9 | 71.2 | 69.5 | 74.5 | 65.9 | 58.1 | 30.4 | 39.3 | 35.1 | 27.4 | 32.9 | 37.2 | |

| Our Baseline | 1.7B | 1.0M | 73.4 | 83.4 | 76.2 | 77.8 | 74.3 | 75.8 | 76.8 | 63.9 | 35.1 | 45.6 | 38.5 | 27.5 | 34.9 | 40.9 | |

| Decoupled Models | P | R | |||||||||||||||

| PrismCaptioner | 1.8B | 70B | 1.9M | 89.2 | 72.7 | 64.6 | 77.8 | 66.0 | 82.3 | 75.4 | 64.0 | 38.8 | 55.8 | 36.7 | 23.0 | 33.1 | 41.9 |

| PrismCaptioner | 7.0B | 70B | 1.9M | 91.5 | 77.0 | 68.1 | 79.9 | 67.5 | 85.8 | 78.3 | 66.7 | 38.5 | 61.5 | 39.8 | 26.7 | 40.4 | 45.7 |

| Baseline | 0.6B | 4.0B | 1.0M | 71.8 | 50.7 | 63.0 | 67.6 | 62.3 | 72.3 | 64.6 | 58.2 | 25.4 | 38.7 | 26.5 | 20.7 | 34.2 | 34.0 |

| Baseline | 1.7B | 4.0B | 1.0M | 79.4 | 59.4 | 65.0 | 71.6 | 64.5 | 76.4 | 69.4 | 62.2 | 30.4 | 46.3 | 32.0 | 29.2 | 35.9 | 39.4 |

| Caption+Think | 0.6B | 1.7B | 2.0M | 84.9 | 80.6 | 60.6 | 74.7 | 66.2 | 83.0 | 75.0 | 60.7 | 37.2 | 51.9 | 38.9 | 27.0 | 42.4 | 43.0 |

| Caption+Think | 1.7B | 4.0B | 2.0M | 89.2 | 84.8 | 68.9 | 80.5 | 72.1 | 84.3 | 80.0 | 64.6 | 37.6 | 53.4 | 48.6 | 33.9 | 56.2 | 49.0 |

| Extract+Think† | 0.6B | 1.7B | 0.4M | 86.9 | 79.8 | 69.9 | 76.6 | 72.5 | 82.1 | 78.0 | 65.2 | 41.7 | 49.7 | 37.5 | 21.9 | 39.8 | 42.6 |

| Extract+Think† | 1.7B | 4.0B | 0.4M | 91.5 | 84.0 | 71.3 | 84.6 | 77.8 | 86.9 | 82.7 | 64.4 | 40.7 | 58.4 | 46.3 | 35.5 | 43.1 | 48.1 |

| Extract+Think | 0.6B | 1.7B | 2.4M | 89.4 | 81.8 | 72.2 | 78.0 | 74.7 | 85.6 | 80.3 | 64.5 | 41.7 | 54.9 | 43.0 | 28.3 | 47.3 | 46.6 |

| Extract+Think | 1.7B | 4.0B | 2.4M | 92.9 | 90.1 | 75.2 | 84.4 | 77.8 | 91.3 | 85.3 | 68.5 | 47.8 | 59.2 | 53.3 | 33.0 | 53.8 | 52.6 |

Table 1. Extract+Think demonstrates extreme effectiveness as a generalist small multimodal model. Even the smaller Extract+Think variant surpasses LLaVA-OneVision-0.5B by up to 19.5% while using 73% fewer visual samples, and outperforms the larger PrismCaptioner model on both in-domain and out-of-domain tasks with a perception module roughly 12x smaller and a reasoning module 41x smaller. The Extract+Think† configuration, trained from scratch under the visual extraction tuning paradigm, demonstrates robust performance using very minimal data.

Extract+Think substantially outperforms decoupled baselines and even competes with end-to-end models trained at vast scale. As shown in Table 1, even our smaller variant surpasses the largest PrismCaptioner model on both in-domain and out-of-domain tasks, with a perception module LLM roughly 12x smaller and a reasoning module 41x smaller. It also outperforms LLaVA-OneVision-0.5B by 12.9% on in-domain data and 19.5% on the out-of-domain MMStar benchmark, while using 73% fewer visual samples.

Visual extraction tuning offers a data-efficient solution for generalist small multimodal models. Looking at our configuration trained from scratch without prior visual training (denoted as Extract+Think† in Table 1), the smaller variant improves over LLaVA-OneVision-0.5B by 9.7% on in-domain data while using 95% fewer visual samples. This setup also outperforms the 1.7B baseline trained directly on the in-domain instruction tuning data, and even exceeds the in-domain performance of the comparable Caption+Think configuration, which was trained on both the in-domain instruction tuning data and 950K additional captioning examples. Overall, these results demonstrate that visual extraction tuning is an extremely effective and efficient paradigm for training small multimodal models.

In this work, we provide a systematic study of how language model downscaling affects multimodal task performance, revealing that visually demanding tasks are disproportionately impacted. Through a decoupled analysis, we identify that both foundational perception and downstream reasoning abilities are central bottlenecks when downscaling LLMs. To address these limitations, we introduce a two-stage perception–reasoning framework that employs visual extraction tuning to enhance the model’s ability to extract relevant visual details across tasks and applies step-by-step reasoning over the extracted data without requiring additional visual training. Our final approach establishes a highly parameter- and data-efficient paradigm for training small multimodal models, setting a new standard for efficiency and performance in this space.

@article{endo2025downscalingintelligence,

author = {Endo, Mark and Yeung-Levy, Serena},

title = {Downscaling Intelligence: Exploring Perception and Reasoning Bottlenecks in Small Multimodal Models},

journal = {arXiv preprint},

year = {2025},

}