day by day: a blog

July 31, 2007

The Year (Something) Happened

Back to the theme of poetic "surprise"....

Back to the theme of poetic "surprise"....

Like Yeats [see Surprise! below], Elizabeth Bishop is another exquisite poet of the unexpected. "One Art", with its sudden eruption of emotion (and exclamations, parentheses, italics) in the final lines, is the paradigm of this strategy. But think of how many other Bishop poems also seem to start with a "drifting hither and thither" as Yeats says, in order to draw out or evade or postpone the moment of arrival at the poem's deep subject. She often seems to begin in a deliberately slow, bland, sometimes even fussy, key. "At the Fishhouses", for instance, wanders loquaciously through an extraordinarily rich but over-detailed anatomy of the shoreline and the speaker's perceptions about "cleated gangplanks", the old man who "sits netting", the "ancient wooden capstan", the Christmas trees, the friendly seal and so on, before it can bear to turn and concentrate on the "knowledge" that is "dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free". But having to batter its way past those psychic defenses, the "sea", like all the other subjects which Bishop will only allow to enter her poetry belatedly, towards the end of a poem, builds an enormous, dammed-up pressure which it would not otherwise have possessed.

"Vague Poem" is a crucial recent addition to Bishop's canon. Written in the mid-1970s and collected in Alice Quinn's edition of Bishop's notebooks and drafts, Edgar Allen Poe and the Juke-Box, this starkly powerful and erotic monologue is now often described as an exception to the norms of the work which Bishop published while she was alive. But in some ways (ways which do not diminish the poem's excellence), it is absolutely typical in its strategically-determined arrangement. So, in "Vague Poem", Bishop lets the poem's "I" move hither and thither apparently aimlessly for roughly the first half of the poem. For example, she allows the speaker to sidetrack herself by a description of the entry to the house she is visiting:

There was nothing by the back door but dirt

or that same dry, monochrome, sepia straw I’d seen everywhere.

Oh, she said, the dog has carried them off.

(A big black dog, female, was dancing around us.)

Parentheses in a poem are invariably a dramatic device, signalling that an important idea has, apparently, come unexpectedly to the author's mind in the course of writing and that this idea must be added to the text, often out of chronological sequence, as an afterthought, before the already established flow of sentences can proceed again. However, a parenthesis (a crucial typographic convention for Bishop, which one sees her using over and over again) can also allow a narrator to avoid reaching the impending climax of a story. Here, the parenthetically encased "big black dog, female,... dancing round us" is both a strange kind of dionysian symbol and an antic emblem of the poem's "dancing around" its own ultimate subject.

Among the finest instances of this often-used delay-and-surprise template in Bishop's poetry is "The Moose", the poem about a beaten-up blue bus "journey[ing] west" at evening through Nova Scotia and News Brunswick towards Boston. I particularly enjoy this poem because here Bishop makes something very unusual — in all honesty, I would prefer to use the word "magical" — out of the "wonder" trope.

Yeats associated the "unforeseen" suggestions of poetry which he loved with a class politics, that is with a moment in which an individualistic rising-above the predictable thoughts of logic, "rhetoric" and the middle-class enacted itself in words. He connected poetic "surprise" with aristocratic self-assertion. Bishop, too, can often sound a subtly patrician tone as the slightly tawdry confusion, mess and chaos of the early part of a poem is transcended in the second half by an epiphany which is equated with "truth" and which usually concludes or seals the poem's meaning. Many of Bishop's poems end with a memorable but slightly unsatisfying bang.

In "The Moose", though, she manages to write about the unexpected bursting in on the routine without denigrating, satirizing or saccharinizing the mundane. Thus, the "illuminated, solemn" rubber boots, and the "hairy, scratchy, splintery" New Brunswick woods are neither transmuted not ironized. And, best of all, there is the reverie-like description of the "old conversation" going on at the back of the bus. As her protagonist overhears it, it reminds of her listening to her grandparents' muffled voices:

uninterruptedly

talking, in Eternity:

names being mentioned,

things cleared up finally;

what he said, what she said,

who got pensioned;

deaths, deaths and sicknesses;

the year he remarried;

the year (something) happened.

She died in childbirth.

That was the son lost

when the schooner foundered....

"Yes . . ." that peculiar

affirmative. "Yes . . ."

A sharp, indrawn breath,

half groan, half acceptance,

that means "Life's like that.

We know it (also death)."

Talking the way they talked

in the old featherbed,

peacefully, on and on,

dim lamplight in the hall,

down in the kitchen, the dog

tucked in her shawl.

This "ordinary", untransfigured world is imbued with happiness, poetry and enigma in ways, and to depths, which poems that trade on narrating a surprising event can very rarely achieve. Subsequently, when the large moose lumbers onto the road, blocking the vehicle's path, the monotonously unvarying timetable of the bus company (a metonymic instance of the modern world's relentless routinizing of all experience) is affronted. The moose ambles up oblivious of human concerns such as time and, like a connoisseur of such things, delicately "sniffs at | the bus's hot hood." The murmured conversations on the bus had had a faintly religious quality: "talking, in Eternity: | names being mentioned, | things cleared up finally." And the moose too has an epiphanic aura as if something sacred had revealed itself. The animal is "Towering... | high as a church," Bishop writes. And she asks (rhetorically):

Why, why do we feel

(we all feel) this sweet

sensation of joy?

But then the moment of "surprise" passes and the regime of the mundane returns. Except that in this poem the mundane has all along been filled with dignity and feeling. The driver wedges the bus's gearstick back into the drive position, and, leaving the moose behind, the ancient vehicle crawls off again down the road into the darkness. The speaker had watched the moose sniff the bus, and now the speaker, sensitized to smells — even those which society defines as unpleasant and which, as a result, hardly ever make their way into poetry — can savour both "a dim | smell of moose, [and] an acrid | smell of gasoline." The wondrous and the ordinary mingle in the nostrils, blending, rather than contrasting, with one another. Bishop's "The Moose" is that rare poem which can represent moments of wonder and surprise without either sentimentalizing or satirizing the mundane, the unexceptional, or the bourgeois contexts which are always the settings for the unexpected or the unforeseen. In a culture which insists for its own ends on maintaining a distinction between the functional (normal) and the aesthetic (abnormal), that quality makes Bishop's poem itself a beautiful, and, ultimately, a useful surprise.

Posted by njenkins at 07:47 PM | Comments (0)

July 30, 2007

The Beets

OK, so it goes something like this — The father was not there. He was probably away on business somewhere. (Later, when the economy nose-dived, his partners forced him to sell his share in the firm for virtually nothing.) The four of them went into a little grocery shop: the harrassed mother, the elder son, aged about eight or nine, the daughter, and the younger son, who was still in a pram. It was late afternoon and chilly. The shop was one in a shabby little row of businesses near their home. There might also have been a newsagent's; a place selling sewing supplies; an off-license filled mainly with beer and cigarettes. Lights were beginning to glow in the dusk. The elder son recalls the row of shops, the pavement, a side-road running past the shops, a iron chain painted white and suspended from short concrete posts which separated the side-road from a strip of grass, then, beyond that, more pavement, and then the main road, heavy with rush-hour traffic.

OK, so it goes something like this — The father was not there. He was probably away on business somewhere. (Later, when the economy nose-dived, his partners forced him to sell his share in the firm for virtually nothing.) The four of them went into a little grocery shop: the harrassed mother, the elder son, aged about eight or nine, the daughter, and the younger son, who was still in a pram. It was late afternoon and chilly. The shop was one in a shabby little row of businesses near their home. There might also have been a newsagent's; a place selling sewing supplies; an off-license filled mainly with beer and cigarettes. Lights were beginning to glow in the dusk. The elder son recalls the row of shops, the pavement, a side-road running past the shops, a iron chain painted white and suspended from short concrete posts which separated the side-road from a strip of grass, then, beyond that, more pavement, and then the main road, heavy with rush-hour traffic.

The bell on the door of the grocery tinkled when they crowded in. They turned left, the mother up ahead manoeuvering the pram round shelf-corners and down the narrow aisles stacked high with bottles, boxes, bags, cans, tubes. The daughter stayed close to the mother. Bored, the elder son lagged behind, just as his own elder son does today. Somewhere several aisles away, the shopkeeper, unseen, gave a loud, self-conscious cough, and made noises with some cans he must have been stacking. There was apparently no-one else in the shop.

The elder son noticed a very large jar, full of sliced beetroot to his left. The vegetables were steeped in brine, which had, though long standing on the shelf, taken on the colour of the sliced beets. The jar looked huge, almost as tall as his brother. Perhaps it was a "family size", offering a distinct saving, pound for pound, over the contents of the normal sized jar. He hated the poisonously sweet taste of beetroot and the way it fell apart in your mouth, as if it were rotten. He still hates beetroot. Now more than ever, in fact.

Here is where it gets mysterious. The elder son remembers being about a step or two past that jar when the huge crash came. It was painfully loud and sudden; it seemed it was about to make his ears explode. He turned round, his mouth open and his eyes popping, and saw a ghastly mess slowly spreading across the linoleum floor. There was a pool of what looked like arterial blood slowly seeping outwards, and in it thousands of tiny shards of glass glinting like stars, many of them embedded in the carcases of the dark beets. Some of the beets had been thrown on top of one another, many others were scattered in a crescent as far as the foot of the shelves on the opposite side of the aisle. He was shocked. The sight was revolting and what he would now describe as sickeningly voluptuous. It looked as if, in the middle of a modest Croydon suburb, a person's body had been split wide open on a grocer's floor. Later, when he saw a picture of a soldier's corpse which had been blown apart in the Ardennes forest by a grenade, his first thought was: "The beets."

"What happened?" his mother asked, staring aghast, perhaps momentarily panicked, at the floor in front of them. "I don't know, Mum," he said. "It fell off. It wasn't me. It wasn't me." "Don't worry," she said, "let's just go home now." He nodded, eyes pointing down still. They walked as quickly as they could towards the till. He was blushing. He felt guilty but he was also certain he had not done anything. His heart was thumping against his ribs; he felt he was going to choke. He felt in danger.

The shopkeeper was behind the counter now, staring. "We want these," the mother said to him quietly and put a block of butter and a box of fishfingers on the counter. "And I'm afraid that a bottle of beetroot has fallen over down that aisle there. But we didn't do it. I'm sorry about that." The shopkeeper must have been about 60. He was thin. His greying hair was grown long down the right side and then, to cover his bald pate, swept up over the crown of his head and held in place there with some liberal applications of Brylcreem. He wore a brown tie under his long, white jacket. His shirt collar was too large for his neck, and his Adam's apple bobbed back and forth as he spluttered at them. He looked so bitter to the boy.

The shopkeeper moved round from behind the counter and spread himself in front of his shop-door. "You are not leaving here until you pay for the beetroot!" he shrieked. "You are not going! That will be seventy-three pence!" The elder son felt horror rippling through his body like waves of heat. The sister and the younger brother stared. A long silence. The mother's lips twitched and, without looking at the enraged man, she muttered "Oh, all right, then." She fumbled in her purse for the change. The greasy shopkeeper retreated back to his till and ching-ed open the cash drawer. It takes a hot pan a long time to cool down. Though the man in white was still incensed, he was trying to conceal his disequilibrium now, and he deposited the money there with a beaming, triumphant look on his face.

They left the butter and the fishfingers inside and, in a rush, the mother bundled the sister and the younger brother through the shop door and down the three brick steps leading to the pavement outside. The elder son went last, petrified that at any moment the shopkeeper was going to hook by the arm, drag him back inside and send him to prison. At last, they stood in a shocked group in the street. The mother was stuffing her purse back into her bag. The children looked at her for instruction, guidance. "Well," she said, "we won't go back to that shop again, will we?" "No, Mum." But the elder son knew that wasn't true. "Come on," the mother said. "Let's get back; it's getting cold." They walked along the pavement in single file, heads bowed, not talking. The elder son lagged behind. Already, he could feel tears of shame and disappointment running like drops from melting icicles down the insides of his cheeks.

In closing, I should mention that I do not believe that he has ever mentioned this trivial incident to more than one person, or at most two. Curiously, though, he insists now that it is something he has never got over.

Posted by njenkins at 07:49 PM | Comments (0)

July 29, 2007

Surprise!

[see also The Year (Something) Happened above] Take an extract from Fondatore's Understudied Concepts in the Structural Functioning of Modern Poetry, vol. 9, (rev. edn. of 1984):

[see also The Year (Something) Happened above] Take an extract from Fondatore's Understudied Concepts in the Structural Functioning of Modern Poetry, vol. 9, (rev. edn. of 1984):

This is "surprise" as illustrated in Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), an image given to Darwin for his book by the great Victorian photographer O. G. Rejlander. (Rejlander was the person the contents of whose studio inspired Charles Lutwidge Dodson to take up photography.) Darwin comments:

"Attention, if sudden and close, graduates into surprise; and this into astonishment; and this into stupefied amazement. The latter frame of mind is closely akin to terror. Attention is shown by the eyebrows being slightly raised; and as this state increases into surprise, they are raised to a much greater extent, with the eyes and mouth widely open. The raising of the eyebrows is necessary in order that the eyes should be opened quickly and widely; and this movement produces transverse wrinkles across the forehead....

"Every sudden emotion, including astonishment, quickens the action of the heart, and with it the respiration. Now we can breathe, as Gratiolet remarks and as appears to me to be the case, much more quietly through the open mouth than through the nostrils. Therefore, when we wish to listen intently to any sound, we either stop breathing, or breathe as quietly as possible, by opening our mouths, at the same time keeping our bodies motionless.... When the attention is concentrated for a length of time with fixed earnestness on any object or subject, all the organs of the body are forgotten and neglected; and as the nervous energy of each individual is limited in amount, little is transmitted to any part of the system, excepting that which is at the time brought into energetic action. Therefore many of the muscles tend to become relaxed, and the jaw drops from its own weight. This will account for the dropping of the jaw and open mouth of a man stupefied with amazement, and perhaps when less strongly affected."

Modernity has made whole swaths of everyday experience infinitely more regulated, stable, repetitive and, if not more repetitive, then more predictable than was once the case. So it is not surprising that, in compensatory fashion, modern culture, and especially modern poetry, places such a premium on the moment of surprise, on the swerve into novelty. For example, "defamiliarization" became a necessary artistic strategy because only what looks strange and novel can be experienced as significant. Yeats (born in 1865, only a few days after Wagner's inexorable Tristan und Isolde had been given its first performance) is full of interesting ideas about the aesthetics of surprise. Thus, for him, the sudden change of tack is a sign of impending insight, for the genuine thinker "approach[es] the truth full of hesitation and doubt." He associates predictablity with the dominance of the managerially- and financially-minded middle-class, which "loves rhetoric because rhetoric is impersonal and predetermined, and it hates poetry whose suggestions cannot be foreseen." Surprise is even more important than truth: "Even if what one defends be true, an attitude of defence, a continual apology, whatever the cause, make the mind barren because it kills intellectual innocence; that delight in what is unforeseen, and in the mere spectacle of the world, the mere drifting hither and thither that must come before all true thought and emotion."

One of Yeats's own most memorable emblems of the unforeseen or of the surprising comes in his January 1914 poem which begins: "Pardon, old fathers, if you still remain | Somewhere in ear-shot for the story's end", the opening poem of Responsibilities. There he celebrates the crazy but memorable, lateral leap of one of his ancestors, William Middleton, a ship-owner and trader, an "Old merchant skipper that leaped overboard | After a ragged hat in Biscay Bay". On deck one moment, abandoning prudence as he suddenly mutates from being a "skipper" to a "leaper", the next the old man is heroically and pointlessly climbing through the waves to rescue a useless hat. An unexpected puff of wind is like a touch of grace, allowing Middleton's hidden, anti-bourgeois qualities to rise into view.

Many Yeats poems veer, twist, decelerate, speed up, or suddenly stop as they enact in their movements this cult of the unforeseen. Think of the end of "In Memory of Major Robert Gregory", for example. Oddly, the poem seems to take several stanzas after its opening before it really begins, that is, before it sets itself to address the ostensible subject of the elegy, Robert Gregory. Then, not long after, just as Gregory's plane unexpectedly plunged to earth, so Yeats's poem — though hardly started in conventional terms — judders to a precipitate halt. Opening verbosity is counterpointed by closing laconicism: "a thought | Of that late death took all my heart for speech." The closing here is a classic instance of "surprise". Remember Darwin: "When the attention is concentrated for a length of time with fixed earnestness on any object or subject, all the organs of the body are forgotten and neglected; and as the nervous energy of each individual is limited in amount, little is transmitted to any part of the system, excepting that which is at the time brought into energetic action. Therefore many of the muscles tend to become relaxed, and the jaw drops from its own weight. This will account for the dropping of the jaw and open mouth of a man stupefied with amazement."(Even as his verse performs the experience of amazement, at another level, Yeats remains in control, as one can see by noting how his mastery of reversals extends here to making "late" in the last line seem like a synonym for "early".)

Yeats treats these formal embodiments of "surprise" as indices of the superior individual's freedom from constraint by the law of the herd. I prefer to think of these disjunctive formal shapes and eruptive thematic moments as something more like algebraic representations of a widely-shared historical experience — surprise is beautiful because it says "It need not be this way." To those relentlessly socialized into a world mainly without surprises, it offers a glimpse into a different mode of experience. Meanwhile, even the actual geo-political "history" which we are living through nowadays seems sombrely unvarying, grimly, direly predictable. It is not that hard to say that the "future looks grim" because it does not seem that difficult to discern what the future will look like. That is, it will unfortunately not be essentially different from the present. Where can deep surprise, which we humans surely need only slightly less than we need security, come from today? One answer is: from theoretical physics. A glance into even a popular book about the universe multiverse shows that. There, whatever is not bewildering or incomprehensible is untrue, and that alone "quickens the action of the heart."

Fondatore (vide supra) concludes with an evasive remark to the effect that much work "remains to be done" by critics seeking to understand the importance of surprise to the modern poem.

Posted by njenkins at 07:52 PM | Comments (0)

July 28, 2007

Haiku

Today, for the first time, we talked about our deaths.

Today, for the first time, we talked about our deaths.

It is no longer

Spring-time for me or my love.

Cherry petals are

my hopes... the future

rushes. Read the names of books

I should have written —

Anarchy and Dust;

Experiments with Crystals;

Evil: A Memoir.

Posted by njenkins at 07:54 PM | Comments (0)

July 27, 2007

Rorty's Binoculars

This morning my older son, Hugo, and I went on a gentle, slow-motion canoe trip through some of the twisting sloughs and inlets of the Baylands Nature Preserve, an area of mudflats and salt- and freshwater marshland in our corner of San Francisco Bay. I always feel happier on the water. It rocks my body and settles my mind, as if even the slight movements of the boat are tipping some of the small, ugly anxieties of my immediate world off the psychic shelves and crevices inside me and that these are drifting slowly downwards till they came to rest on the dark, chocolate-y silt-floor far below consciousness. Wind and waves constitute relief; a kind of spring-cleaning by means of the lapping water on a hull.

This morning my older son, Hugo, and I went on a gentle, slow-motion canoe trip through some of the twisting sloughs and inlets of the Baylands Nature Preserve, an area of mudflats and salt- and freshwater marshland in our corner of San Francisco Bay. I always feel happier on the water. It rocks my body and settles my mind, as if even the slight movements of the boat are tipping some of the small, ugly anxieties of my immediate world off the psychic shelves and crevices inside me and that these are drifting slowly downwards till they came to rest on the dark, chocolate-y silt-floor far below consciousness. Wind and waves constitute relief; a kind of spring-cleaning by means of the lapping water on a hull.

Hugo and I and the rest of of our group saw plenty of interesting wildlife today: bat rays flopping through the shallow creek in search of food, the tiny camera-flashes of small fish's backs breaking the rippling surface for a moment, even a seal — head raised, looking back and forth cautiously, as if it were expecting an ambush — pushing its way up an inlet. We scooped handfuls of the rich, black Bay mud, which the industrial processes of the Gold Rush have left probably permanently contaminated with mercury, up out of the water. With a slightly mocking smile our guide, calling from another canoe, made me repeat after her: "In my hand I am holding over 40,000 small organisms." When I bent my face down to it, the mud (full of over 40,000 bits of life, much of it feeding on dead organic matter) smelled sulphurous.

The Baylands is one of the most important birding areas around here. As we canoed slowly in and out of the marsh's trickling channels we saw black-billed and Western gulls, a blue heron, several kinds of egret, sandpipers, white and grey pelicans, high above us a turkey vulture wheeling on thermals, and what looked to me like scores of swifts. With the help of a chart, the scholarly Hugo correctly identified a small group of marbled godwits standing on a mudflat right at the border to a shapeless kingdom of crabgrass. The godwits' have a long, delicate beak with a subtle upward curve towards its tip. Their chests are a softly-barred brown and chesnut colour, which looks like a patch of cloudy autumnal evening sky.

Though today the Baylands are always replete with birds, these are nonetheless the hardy remnants of the great tribes which once congregated here. In the later 18th century Caucasian explorers of the land around San Francisco Bay noted that whenever there was a sharp sound — perhaps a gun firing, someone emitting a croaking, syphilitic cough, or a bottle smashing as it dropped onto a rock — a huge, swarming cloud of birdlife would rise instantly into the air, crying and calling and darkening the sky and the land beneath it.

There were many American avocets around today, looking almost exactly like the example which Audubon created for his giant album Birds of America. "Almost exactly", but not quite. My eyes kept turning back to these birds amongst all the others in the sky and on the mud, so I suppose that I must have some special, half-recognised fondness for them. Audubon's American avocet looks militant, active, self-confident, like a middle-class entrepreneur, a reader of Poor Richard's Almanack, striding hungrily across the mud as bountiful "opportunities" arise for it to "acquire" bugs and worms. It must largely have been due to the time of day, but the American avocets we saw this morning were identical in markings to the one Audubon painted. Yet these birds, unlike his, were standing absolutely still, all seeming to stare off in the same direction into the hot, hazy distance as if they were trying to remember something which they had collectively forgotten. In their summer plumage, their necks and heads have turned a spectacular pale reddish-brown, making it look as if they are experiencing a warm blush without any of the attendant human embarrassment or guilt.

As we drove home afterwards, I started thinking about Richard Rorty, who died little more than a month and a half ago. Rorty had a "sunset" appointment at Stanford, teaching in the Comparative Literature Department. As far as I can tell, to many professors here he was a well-liked, and strongly admired, colleague. I hardly knew him at all. He was a hefty man, and I winced at his beefy handshake and smiled into his seemingly indifferent eyes just a few times. But we never exchanged anything more than the most cursory pleasantries. I had the feeling that, when we did, his mind was somewhere else, a bit like the group of avocets which we paddled past earlier, and, although I felt a bit crestfallen after the experience (aren't I interesting too?), at the same time I admired and envied his evident intellectual self-preoccupation.

As for his philosophy — well, my opinion of it is about as useful to any serious student of Rorty's work as his opinion of, say, The Faerie Queene probably would have been to a specialist in Elizabethan poetics. To have rebelled in the way he did against his own philosophical training gave him an impressive intellectual stature in my eyes. But, for what it's worth, and in as far as I understand what he was writing about, I feel that there is something uncomfortably cosy about the Pragmatism which he espoused so artfully as his act of rebellion. We form into groups, we talk about problems in ways which those of us who are inside the group understand but which are meaningless to those others who are not embedded within the same social-linguistic co-ordinates as ourselves. What we say is never really a statement about "the world" but just part of a sophisticated, higher-level linguistic game. We need not agree and we need not be upset about not agreeing because we can always keep talking, and, anyway, little (or nothing) is absolutely at stake in these discussions because our verbal mirrors are just reflecting other mirrors' reflections of mirrors. Philosophy never holds a mirror up to nature. It seems to me a bit like a version of social interaction based on the premise that everyone's life everywhere is like that of a tenured professor — we do our own thing, we go our own ways; you do your thing, you go yours. And we will meet again next week at the same time. As for scrambling for food, burying babies, stealing out of desperation, murdering a rival pimp and seizing his territory — ah, even as we speak someone somewhere else is doubtless doing that for us. In a very muted key, Rorty's views seem like those of a Nietzschean "haunted thinker".

But there was an interesting rift between Rorty's philosophy and what very little I know about his personal conduct. As a person, Rorty's heart was evidently just where I think anyone's heart should be. His mother's father was the socially-involved theologian Walter Rauschenbusch. His father, James, had been a poet (Children of the Sun and Other Poems, 1926) and journalist, closely associated in the 1930s and 1940s with Partisan Review and with New York's anti-Stalinist left. Richard Rorty too was politically progressive and had a strong social conscience. He was never more decent, sensible and honourable than when he wrote to the New York Times not that long ago ridiculing the idea that a person like himself who, after a successful career, had more than enough money to look after his needs in his post-retirement years should have a "right" to social security payments as well. Of course, his selfless statement fell, as he knew it would, clattering into an otherwise silent void.

My most pleasurable memory of Rorty, and the one which best serves and encourages a philosophical illiterate such as myself, is of a silent, off-campus non-encounter. It must have happened about three years ago. Siri, Hugo, Owen and I had climbed out of our car and were entering the Baylands a little further south than where Hugo and I canoed today. It was at the marsh entrance between Adobe Creek and Charleston Slough, near a point where in the autumn you can often see great flocks of American White Pelicans resting during their annual migration towards the Gulf of Mexico. As we bundled ourselves through the Nature's Preserves gate, Rorty came striding along in the opposite direction, a pair of very expensive-looking binoculars in his hands. We exchanged nothing more than glances as we passed. But, afterwards, while I tugged gently at Owen's sleeve, trying to urge him in a stage-actor version of paternal firmness to speed his reluctant steps up a bit, I felt an exquisite amalgam of embarrassment, sympathy and puzzlement. Rorty was a bird-watcher.

I don't care much what I think about the durability of Richard Rorty's work. Surely no-one else does either. When I remember him, what comes back instead of irrelevant judgements is that subtly odd moment at the edge of San Francisco Bay. Somehow, while walking briskly down a straight path, he swerved into authenticity in my mind. It made me understand that he had what every writer needs — a hinterland, a psychic place to return to at will, privately. This hinterland must be cut off from direct connection with (and is, perhaps, preferably antithetical to) his or her public "opinions", loyalties, books. In Rorty's case, the contemplative and unassertive practice of bird-watching may have moved him into that place in his head. The man who debunked the fiction that philosophy could give us a reflection of the world as it really is, spent many solitary hours sitting still and probably feeling chilly, as he gazed through powerful lenses at the markings and habits of these insignificant "others", wholly alien to us, whose province is as much sky as earth.

Maybe that archetypal journey from the private place to the public one, or from the public one to the private, is traced out surreptitiously in everything a good writer composes? Remembering Rorty and his binoculars certainly convinces me that one of the essential markers of "truth" in language (as of truth in life) is that we recognize it first because, seeming to emerge suddenly out of nothing, it comes as an absolute, and vaguely disturbing, surprise.

Posted by njenkins at 07:55 PM | Comments (0)

July 26, 2007

Names

The problem: "Large numbers of containers, particularly beverage cans, are conventionally opened by pulling off a tear strip which is removable together with the attached ring tab. The severed tear strip with attached tab may be carelessly discarded with undesirable consequences, such as litter and a hazard to bare feet. Moreover, many cans with easy-open ends of this sort are made of aluminum alloys which can be produced with less expenditure of energy through recycling than from the original ore, and the metal in the tear strip and tab are more readily collected and recycled of the tear strip and tab remain with the can body after opening of the can."

The problem: "Large numbers of containers, particularly beverage cans, are conventionally opened by pulling off a tear strip which is removable together with the attached ring tab. The severed tear strip with attached tab may be carelessly discarded with undesirable consequences, such as litter and a hazard to bare feet. Moreover, many cans with easy-open ends of this sort are made of aluminum alloys which can be produced with less expenditure of energy through recycling than from the original ore, and the metal in the tear strip and tab are more readily collected and recycled of the tear strip and tab remain with the can body after opening of the can."

The solution: "the invention provides constructions wherein the tab for opening a panel in a container wall is capable of having one end pressed against the panel to open it wide without putting the tab in a position where it will obstruct more than a small portion of the opening left by the panel in its open position. Furthermore, the tab nose is positioned in accordance with the invention away from any rupturable score line, thereby reducing the chances of inadvertent rupture through pressure on the tab during storage and transportation. The invention further teaches initiation of rupture of the score line adjacent the rivet or the like securing the tab to the container wall, and completing rupture through propagation of the initial crack away from adjacent the rivet position and then around and back again to leave only a small unbroken part of the wall to hinge the panel. The means securing the tab to the container wall is secured to the wall outside the area of the removable panel, with some play preferably provided to permit the liftable end of the tab to be raised conveniently preliminary to initial rupture of the score line.

"The opening construction of the invention requires a tab which must be stiff against transverse bending and yet flexible and tough enough at the connection between the tab and end wall to permit lifting and retracting the tab without causing a fatigue crack at the connection. The invention provides a tab construction meeting these requirements. It is particularly adapted to be used in conjunction with the applicant’s novel opening construction, but may also have application in other opening constructions."

This is from U.S. Patent 3967752 [thanks, Google], filed in November 1975, for Daniel F. Cudzik's now all-but-universally-dispersed invention of what the patent calls the "Easy-Open Wall" in a soda can, or, in everyday parlance, the "stay-top". It's that little rivetted lever and the adjacent aluminium flap in the roof of your soda can. I like very much the notion alluded to in the patent that the proper use of this device is so ingeniously self-evident that it can actually "teach" even neophyte purchasers of a beverage how to penetrate into the otherwise relatively durable and self-contained object in their hands. When you pull up the lever the seal is broken and the flap drops like a miniature trap-door, allowing you access to your soda. By the way, I'm still working on the Diet Coke whose stay-top I popped just a few minutes ago while beginning this post.

The question I find myself asking is — We know that patent descriptions are highly complex, artful texts. They must be specific enough to define very intimately the unique nature of the invention for which a patent is claimed, while being at the same time, in order to ward off bucaneering rivals, inexplicit enough to withhold some crucial details about how exactly this invention can be reproduced or manufactured. But could you describe the construction of that small verbal object a poem as lucidly, exhaustively, fully and, in its awkward way, as beautifully as this patent's language does the construction and functioning of the stay-top? My answer on all counts is — unfortunately, No. But it is my ambition to reach the level of competence where, in writing about poetry, I can produce at least an approximation of such fine-grained precision.

Cheers! Drink it up!

Posted by njenkins at 07:56 PM | Comments (0)

July 25, 2007

Prayer

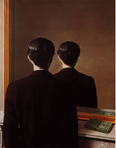

This is Magritte's Reproduction interdite (1937). It is to be an image of a man with no face. Or rather an image of a man whose face the painter insists on concealing from us and, if we accept the fiction embodied in the painting for a moment, a man whose face the painter also sadistically insists on concealing from the man himself. Paradoxically, though, don't we learn something important about this creature's existence and identity from not being able to see him "face to face", something that a predictable, frontal encounter would not allow us to glimpse? It makes me imagine a literary critic's prayer. It might run something like this: "Please God [lots of stuff to do with mendacity, vanity, self-pity etc etc are omitted here for the sake of my argument], and finally, please let me write a serious essay on the poetry of Adrienne Rich without allusion to the fact that she is American, and another one on Seamus Heaney that does not contain the words 'Irish' or 'Ireland', and one as well on Maria Tsevtaeva that mentions neither the Soviet Union or Stalin. Thank you." Would God (if He exists) allow such requests? Perhaps He already has but we are unaware of His permission. Would such an ascesis be feasible? Current norms and protocols suggest that it wouldn't be. That would be all the more reason to attempt it. My intuition is that such essays (try to imagine the experience of reading them) would be revelatory. They would be revelatory in a pleasurable way about the poetry concerned. Perhaps they would also tell one something slightly less palatable, something which one didn't know before, about what goes on behind the face of that increasingly sour and irritating stranger who glances silently at one from the mirror each godforsaken morning?

This is Magritte's Reproduction interdite (1937). It is to be an image of a man with no face. Or rather an image of a man whose face the painter insists on concealing from us and, if we accept the fiction embodied in the painting for a moment, a man whose face the painter also sadistically insists on concealing from the man himself. Paradoxically, though, don't we learn something important about this creature's existence and identity from not being able to see him "face to face", something that a predictable, frontal encounter would not allow us to glimpse? It makes me imagine a literary critic's prayer. It might run something like this: "Please God [lots of stuff to do with mendacity, vanity, self-pity etc etc are omitted here for the sake of my argument], and finally, please let me write a serious essay on the poetry of Adrienne Rich without allusion to the fact that she is American, and another one on Seamus Heaney that does not contain the words 'Irish' or 'Ireland', and one as well on Maria Tsevtaeva that mentions neither the Soviet Union or Stalin. Thank you." Would God (if He exists) allow such requests? Perhaps He already has but we are unaware of His permission. Would such an ascesis be feasible? Current norms and protocols suggest that it wouldn't be. That would be all the more reason to attempt it. My intuition is that such essays (try to imagine the experience of reading them) would be revelatory. They would be revelatory in a pleasurable way about the poetry concerned. Perhaps they would also tell one something slightly less palatable, something which one didn't know before, about what goes on behind the face of that increasingly sour and irritating stranger who glances silently at one from the mirror each godforsaken morning?

Posted by njenkins at 07:57 PM | Comments (0)

July 24, 2007

Vega

We went communal star-gazing out in the countryside in Los Altos Hills on Saturday night. The kids were bored stiff; the parents frustratingly mesmerized. I got one of the star-geeks who was on-hand to trace out the Lyra constellation for me with his laser wand. Ancient astronomers believed that the constellation was Orpheus's lyre, which the gods had placed in the darkened sky after the Bacchae, down on earth, had torn Orpheus to pieces and thrown his head into the river Hebrus. The crown or neck of the Lyra constellation is Vega, "only" about 25 light years away and the second brightest star in the northern hemisphere. Almost directly overhead, Vega was very easy to pick out on Saturday. Finding the rest of the constellation was harder, because its other constituent stars are much much fainter. You have to thread your eye slowly from dot to palely glimmering dot, ignoring so many other glints of light in that region of the sky in order to isolate what could be seen (once you've decided to search for such a thing) as a lyre's body. Auden has a poem which uses Vega as a reference point. That's what first got me going on finding the constellation. (What an admission! Where is your sense of wonder over nature, man? Are you only interested if Auden was interested?) Seeing Lyra, mapping it, was a bit like the experience of making sense of a poem for the first time — crawling cognitively from point to point, disregarding so much as "background", until a vague, skeletal shape stands out, a shape that in this case is that of an instrument left behind after its owner's demise. Did the Greeks who gazed at Lyra have the idea that, because light travels so infinitely further than sound, as we look up at the constellation we should also "hear" the desolate spiritual silence of the murdered poet's instrument, the bereft quality like that of a single bloody shoe left on the sidewalk after an explosion?

We went communal star-gazing out in the countryside in Los Altos Hills on Saturday night. The kids were bored stiff; the parents frustratingly mesmerized. I got one of the star-geeks who was on-hand to trace out the Lyra constellation for me with his laser wand. Ancient astronomers believed that the constellation was Orpheus's lyre, which the gods had placed in the darkened sky after the Bacchae, down on earth, had torn Orpheus to pieces and thrown his head into the river Hebrus. The crown or neck of the Lyra constellation is Vega, "only" about 25 light years away and the second brightest star in the northern hemisphere. Almost directly overhead, Vega was very easy to pick out on Saturday. Finding the rest of the constellation was harder, because its other constituent stars are much much fainter. You have to thread your eye slowly from dot to palely glimmering dot, ignoring so many other glints of light in that region of the sky in order to isolate what could be seen (once you've decided to search for such a thing) as a lyre's body. Auden has a poem which uses Vega as a reference point. That's what first got me going on finding the constellation. (What an admission! Where is your sense of wonder over nature, man? Are you only interested if Auden was interested?) Seeing Lyra, mapping it, was a bit like the experience of making sense of a poem for the first time — crawling cognitively from point to point, disregarding so much as "background", until a vague, skeletal shape stands out, a shape that in this case is that of an instrument left behind after its owner's demise. Did the Greeks who gazed at Lyra have the idea that, because light travels so infinitely further than sound, as we look up at the constellation we should also "hear" the desolate spiritual silence of the murdered poet's instrument, the bereft quality like that of a single bloody shoe left on the sidewalk after an explosion?

Posted by njenkins at 07:57 PM | Comments (0)

July 23, 2007

Is Anyone There?

This morning I can't get this photograph out of my mind. It's Rodchenko's "At the Telephone" (1928); there's a print at MoMA in NYC. I once thought of it as "just" an extraordinary example of the "New Vision", of a stark, photographic formalism. But in a class discussion a while back Justin Eichenlaub pointed out that it was taken just as Stalin's state-sanctioned paranoia was emerging. The photographer is not only looking at the worker from a new angle. He is also secretly surveying her, perhaps eavesdropping. A whole burgeoning culture of surveillance is represented here as well as a formalist aesthetic of defamiliarization. Perhaps that's why I can't stop myself from recalling the image over and over today. Really, no-one is anonymous anymore. Our continuing freedom to do and read and say what we want is now predicated on our remaining of complete practical insignificance to the State.

This morning I can't get this photograph out of my mind. It's Rodchenko's "At the Telephone" (1928); there's a print at MoMA in NYC. I once thought of it as "just" an extraordinary example of the "New Vision", of a stark, photographic formalism. But in a class discussion a while back Justin Eichenlaub pointed out that it was taken just as Stalin's state-sanctioned paranoia was emerging. The photographer is not only looking at the worker from a new angle. He is also secretly surveying her, perhaps eavesdropping. A whole burgeoning culture of surveillance is represented here as well as a formalist aesthetic of defamiliarization. Perhaps that's why I can't stop myself from recalling the image over and over today. Really, no-one is anonymous anymore. Our continuing freedom to do and read and say what we want is now predicated on our remaining of complete practical insignificance to the State.

Posted by njenkins at 07:58 PM | Comments (0)

July 22, 2007

Alonso in the Rain

Fernando Alonso in a McLaren-Mercedes wins the GP of Europe in a crazy, rain-punctuated race at the Nürburgring, passing Felipe Massa's Ferrari with only five or so laps remaining. Alonso is my favourite driver. I am ecstatic! The best races, like this one, always involve a change of leader in the final stages. Scuderia Ferrari is the most entrenched team in F1, the team with the longest competitive history (Ferraris made their debut in F1 in 1948 and a Ferrari first won a Grand Prix in 1951). I feel unpleasantly edgy about the team's power and know-how, so it was delightful to see Alonso muscle his way past Massa's car, surviving as he did Massa's attempt to nudge him into a spin. Afterwards, in the area behind the presentation podium, they went at each other like bickering children. "You broke my sidepod!" "You win and you say this?!" It seemed clear that the desperate Massa did try to push Alonso off the road. But, according to the drivers' unofficial code of honour, the victor Alonso should not have called Massa after the race on his mad behaviour because Alonso had survived it and won. But Alonso has never been very good at mouth-management offtrack. Oh, so much sensitivity and determination in the car, so much human ordinariness out of it! I loved that too.

Fernando Alonso in a McLaren-Mercedes wins the GP of Europe in a crazy, rain-punctuated race at the Nürburgring, passing Felipe Massa's Ferrari with only five or so laps remaining. Alonso is my favourite driver. I am ecstatic! The best races, like this one, always involve a change of leader in the final stages. Scuderia Ferrari is the most entrenched team in F1, the team with the longest competitive history (Ferraris made their debut in F1 in 1948 and a Ferrari first won a Grand Prix in 1951). I feel unpleasantly edgy about the team's power and know-how, so it was delightful to see Alonso muscle his way past Massa's car, surviving as he did Massa's attempt to nudge him into a spin. Afterwards, in the area behind the presentation podium, they went at each other like bickering children. "You broke my sidepod!" "You win and you say this?!" It seemed clear that the desperate Massa did try to push Alonso off the road. But, according to the drivers' unofficial code of honour, the victor Alonso should not have called Massa after the race on his mad behaviour because Alonso had survived it and won. But Alonso has never been very good at mouth-management offtrack. Oh, so much sensitivity and determination in the car, so much human ordinariness out of it! I loved that too.

Posted by njenkins at 08:00 PM | Comments (0)

With the exception of the interspersed quotations, all writing © 2007-10 by Nicholas Jenkins [back]