Due Friday, March 1 at 4:00 pm Pacific

Solutions are available!

What can you do with regular expressions? What are the limits of regular languages? And how does the material on discrete structures from the first half of this quarter come into play in this latter half on automata and computation? In this seventh problem set, you'll explore the answers to these questions along with their practical consequences.

As always, please feel free to drop by office hours, ask on EdStem, or send us emails if you have any questions. We'd be happy to help out.

Good luck, and have fun!

Grading

- Submissions received by Friday 3/1 at 4PM PT will earn a small "on-time" bonus. We will add the bonus points onto your assignment score (approximately 5% of the total points available for this assignment).

- There is a penalty-free 48-hour "grace period" for late submission. The grace period allows you to submit the assignment after the deadline, with no impact on your grade. Therefore, the latest you can submit within the grace period is Sunday 3/3 at 4PM PT.

- The Sunday deadline is firm and you will not be able to use additional late days on this assignment. To be clear: unless you have an extension due to OAE accommodations, we will not accept any submissions after Sunday at 4PM.

- Problem Set 8 will still be released according to our normal assignment cadence.

Starter Files

Here are the starter files for the problems you'll submit electronically:

Unpack the files somewhere convenient and open up the bundled project.

If you would like to type your solutions in $\LaTeX$, you may want to download this template file where you can place your answers:

Problem One: Designing Regular Expressions

Below are a list of alphabets and languages over those alphabets. For each language, write a regular expression for that language. Provide your answers by downloading the starter files for Problem Set Seven from Canvas and editing the file res/RegularExpressions.regexes. (Unlike the DFA/NFA editor from last time, you’ll need to manually edit these files by opening them in Qt Creator.) Feel free to test your answers locally, and submit your work on GradeScope.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}, \mathtt{c}, \mathtt{d}, \mathtt{e}}$. Write a regular expression for the language $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat$ the letters in $w$ are sorted alphabetically }. For example, $\mathtt{abcde} \in L\text,$ $\mathtt{bee} \in L\text,$ $\mathtt{a} \in L\text,$ and $\varepsilon \in L\text,$ but $\mathtt{decade} \notin L\text.$

-

Write a regular expression for the complement of the language from part (i) of this problem.

Like NFAs and unlike DFAs, there isn't a simple construction that starts with a regex for $L$ and turns it into a regex for $\overline{L}$.

-

On Unix-style operating systems like macOS or Linux, files are organized into directories. You can reference a file by giving a path to the file, a series of directory names separated by slashes. For example, the path

/home/username/might represent a user’s home directory, and a path like/home/username/Documents/PS7.texmight represent that person’s solution to this problem set. Paths that start with a slash character are called absolute paths and say exactly where the file is on disk. Paths that don’t start with a slash are called relative paths and say where, relative to the current folder, a file can be found. For example, if I’m logged into my computer and am in my home folder, I could look up the fileDocuments/PS7.texto find my solution to this problem set.The general pattern here is that a file path consists of a series of directory or file names separated by slashes. That path might optionally start with a slash, but isn’t required to, and it might optionally end with a slash, but isn’t required to. However, you can’t have two consecutive slashes.

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{/}}$. Write a regular expression for $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w$ represents the name of a file path on a Unix-style system }. For example, $\mathtt{/aaa/a/aa} \in L$, $\mathtt{/} \in L$, $\mathtt{a} \in L$, $\mathtt{/a/a/a/} \in L$, and $\mathtt{aaa/} \in L$, but $\mathtt{//a//} \notin L$, $\mathtt{a//a} \notin L$, and $\varepsilon \notin L$.

Fun fact: this problem comes from my experience in industry, where we had a bug in our code that arose when someone wrote the wrong regex for this language. Oops.

-

Suppose you are taking a walk with your dog on a leash of length two. Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{y}, \mathtt{d}}$ and let $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w$ represents a walk with your dog on a leash where you and your dog both end up at the same location }. For example, we have $\mathtt{yyddddyy} \in L$ because you and your dog are never more than two steps apart and both of you end up four steps ahead of where you started; similarly, $\mathtt{ddydyy} \in L$. However, $\mathtt{yyyydddd} \notin L$, since halfway through your walk you’re three steps ahead of your dog; $\mathtt{ddyd} \notin L$, because your dog ends up two steps ahead of you; and $\mathtt{ddyddyyy} \notin L$, because at one point your dog is three steps ahead of you.

Write a regular expression for $L$.

Note that, unlike Problem Set Six, you and your dog must end at the same position.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{M}, \mathtt{D}, \mathtt{C}, \mathtt{L}, \mathtt{X}, \mathtt{V}, \mathtt{I}}$ and let $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w$ is number less than $2,000$ represented in Roman numerals }. For example, $\mathtt{CMXCIX} \in L$, since it represents the number $999$, as are the strings

L(50),VIII(8),DCLXVI(666),CXXXVII(137),CDXII(412), andMDCXVIII(1,618). However, we have that $\mathtt{VIIII} \notin L$ (you'll never have fourI's in a row; useIXorIVinstead), that $\mathtt{MM} \notin L$ (it's a Roman numeral, but it's for $2,000$, which is too large), that $\mathtt{VX} \notin L$ (this isn't a valid Roman numeral), and that $\mathtt{IM} \notin L$ (the notation of using a smaller digit to subtract from a larger one only lets you useIto prefixVandX, orXto prefixLandC, orCto prefixDandM). The Romans didn't have a way of expressing $0$, so to make your life easier we'll say that $\varepsilon \in L$ and that the empty string represents $0$. (Oh, those silly Romans.)Write a regular expression for $L$.

As a note, we’re using the “standard form” of Roman numerals. You can see a sample of numbers written out this way via this link.)

Problem Two: Regexes and Accessible Design

Regular expressions are frequently used in software systems to validate user input. For example, if a form on a website requires an email address, the website might use a regular expression to confirm that what the user types in is a valid email address before letting them submit the form.

It’s good for websites to validate their data. It helps prevent people from making accidental mistakes when signing up or giving contact information, and it can help prevent spam. However, there are risks with validating data too strictly. It’s unfortunately common for websites to reject valid inputs because the person designing the website made an unwarranted assumption about what those inputs are supposed to look like.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. In “real-world” regexes, the notation [A-Z] means the same thing as our Theoryland regex $\mathtt{(A \cup B \cup C \cup \dots \cup Z)}$, and the notation [A-Za-z] has the same meaning as our Theoryland regex $\mathtt{(A \cup B \cup \dots \cup Z \cup a \cup b \cup \dots \cup z)}$. Now, suppose a website asks the user to enter their full legal name. They use the following regex to do so:

[A-Z][a-z]+ [A-Z][a-z]+ [A-Z][a-z]+

For example, this would match the strings Stephen Gerald Breyer and Sonia Maria Sotomayor.

Give an example of the full name of a real person – ideally someone you know, but it could also be a celebrity or other famous person – that does not match this regular expression. Briefly explain why their name doesn’t match. Then, give two more examples of names that aren’t matched by this regular expression, each of which should fail to match the regex for different reasons.

The takeaway from this problem is to be careful when validating user data. The human experience is rich and varied and many assumptions that you might take as basic and fundamental might be completely different from others’ lived experiences. If you make unwarranted assumptions about user data – even as something as basic as “what is your name?” – you might lock people out from using a product or service.

Problem Three: Finite Languages

A language $L$ is called finite if $L$ contains finitely many strings (that is, $\abs{L}$ is a natural number). Given a finite language $L$, explain how to write a regular expression for $L$. Briefly justify your answer; no formal proof is necessary. This shows that all finite languages are regular.

Watch for edge cases!

Problem Four: State Elimination

The state elimination algorithm gives a way to transform a DFA or NFA into a regular expression. It's a beautiful algorithm once you get the hang of it. In this problem, you’ll use the state elimination algorithm to produce a regular expression for a language.

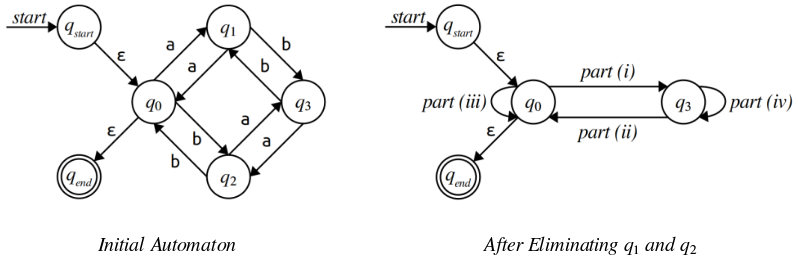

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$ and let $L$ = { $w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w$ has an even number of $\mathtt{a}$'s and an even number of $\mathtt{b}$'s}. Below to the left is a finite automaton for $L$ that we've prepared for the state elimination algorithm by adding in a new start state $q_{start}$ and a new accept state $q_{end}$. If you run two steps of the state elimination algorithm on the above automaton, first eliminating state $q_1$, then eliminating state $q_2$, you will get an automaton whose shape matches the diagram on the right.

Edit the file res/StateElimination.regexes to answer the following questions.

-

ii. iii. iv. What regular expressions go at the indicate positions in the diagram?

Remember that to eliminate a state $q$, you should identify all pairs of states $q_{in}$ and $q_{out}$ where there’s a transition from $q_{in}$ to $q$ and from $q$ to $q_{out}$, then add shortcut edges from $q_{in}$ to $q_{out}$ to bypass state $q$. Remember that $q_{in}$ and $q_{out}$ may be the same state. To help you check your work: there are four such pairs for state $q_1$.

If you’ve done everything properly, at the end of this stage, none of these transitions should use the Kleene star.

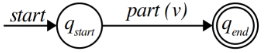

Now, eliminate $q_3$ and then $q_0$. Your automaton should look like this:

The regular expression on this edge has the same language as the original automaton!

-

What regular expression goes at this spot in the above diagram?

This is where you’ll start seeing Kleene stars.

Optional but recommended activity: look at the regular expression you ended up with in part (v) of this problem. How does it work? That is, how does that regular expression match all and only strings with an even number of a’s and an even number of b’s?

Problem Five: Distinguishability

The concepts of distinguishability and distinguishing sets play a key role in the Myhill-Nerode theorem. This problem explores them in more depth.

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$ and let $L = \Set{ w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat \text{the number of }\mathtt{a}\text{'s in }w\text{ is a multiple of three }}\text.$ Which of the following pairs of strings are distinguishable relative to $L$? For each pair that is distinguishable relative to $L$, give us the shortest string $w \in \Sigma^\star$ such that exactly one of $xw$ and $yw$ is in $L$. (If multiple strings are tied for having the shortest length, you can pick any one of them.) No justification is necessary.

- $x = \mathtt{a}, y = \mathtt{aa}\text.$

- $x = \mathtt{a}, y = \mathtt{aaa}\text.$

- $x = \mathtt{aa}, y = \mathtt{aaa}\text.$

- $x = \mathtt{a}, y = \mathtt{aaaa}\text.$

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$ and let $L = \Set{ w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w \text{ contains } \mathtt{aa} \text{ as a substring }}\text.$ Which of the following are distinguishing sets for $L$? For each set that isn't a distinguishing set, give us a pair of distinct strings from the set that aren't distinguishable relative to $L$. No justification is necessary.

- $\Set{ \mathtt{a}^n \suchthat n \in \naturals }\text.$

- $\emptyset\text.$

- $\Sigma^\star\text.$

- $\Set{\mathtt{abba}}\text.$

- $\Set{\mathtt{abba}, \mathtt{abbababba}}\text.$

- $\Set{\varepsilon, \mathtt{a}, \mathtt{aa}}\text.$

- $\Set{\varepsilon, \mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}\text.$

-

Let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$ and consider this language $L\text:$

\[L = \Set{ w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w \text{ has even length and its first half does not equal its second half } }\text.\]Give a distinguishing set $S$ for $L$ containing four strings. Then, for each pair of distinct strings $x, y \in S$, show that they're distinguishable by giving a string $w$ where exactly one of $xw$ and $yw$ belongs to $L$.

-

As above, let $\Sigma = \Set{\mathtt{a}, \mathtt{b}}$ and let $L$ be this language:

\[L = \Set{ w \in \Sigma^\star \suchthat w \text{ has even length and its first half does not equal its second half} }\text.\]Prove that $L$ is not regular.

See if you can find a way of generalizing the distinguishing set you found in part (iii) to have four strings, then five, and eventually infinitely many.

Optional Fun Problem: Birget’s Theorem

The Myhill-Nerode theorem we proved in lecture is actually a special case of a slightly broader theorem that says the following:

Theorem: Let $L$ be a language over $\Sigma$ and $S \subseteq \Sigma^*$ be a distinguishing set for $L$. Then every DFA for $L$ must have at least $|S|$ states.

It's not that difficult to adapt the proof of the Myhill-Nerode theorem from lecture to prove this version of the theorem. For brevity's sake we aren't going to ask you to do this, but you are welcome to tinker around with this result if you'd like.

Unfortunately, distinguishability is not a powerful enough technique to lower-bound the sizes of NFAs. In fact, it's in general quite hard to bound NFA sizes; there's a million-dollar prize for anyone who finds a efficient algorithm (for some precise definition of “efficient”) that, given an arbitrary NFA, converts it to the smallest possible equivalent NFA!

Although it's generally difficult to lower-bound the sizes of NFAs, there are some techniques we can use to find lower bounds on the sizes of NFAs. Let $L$ be a language over $\Sigma$. A generalized fooling set for $L$ is a set $\mathscr{F}$ of pairs of strings in $\Sigma^\star$ with the following properties:

- For any $(x, y) \in \mathscr{F}$, we have $xy \in L$.

- For any distinct pairs $(x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2) \in \mathscr{F}$, we have $x_1y_2 \notin L$ or $x_2y_1 \notin L$ (this is an inclusive OR.)

Prove that if $L$ is a language and there is a generalized fooling set $\mathscr{F}$ for $L$ that contains $n$ pairs of strings, then any NFA for $L$ must have at least $n$ states.