Due Friday, May 10 at 3:00 pm Pacific

Solutions are available!

This problem set – the last one purely on discrete mathematics – is designed as a cumulative review of the topics we’ve covered so far and a proving ground to try out your newfound skills with mathematical induction. The problems here span all sorts of topics and we hope that it serves as a fitting coda to our whirlwind tour of discrete math!

We recommend that you read the Guide to Induction before starting this problem set. It contains a lot of useful advice about how to approach problems inductively, how to structure inductive proofs, and how to not fall into common inductive traps. Additionally, before submitting, be sure to read over the Induction Proofwriting Checklist for a list of specific things to watch for in your solutions before submitting.

As a note on this problem set – normally, you're welcome to use any proof technique you'd like to prove results in this course. On this problem set, we've specifically asked on some problems that you prove a result inductively. For those problems, you should prove those results using induction or complete induction, even if there is another way to prove the result. (If you'd like to use induction in conjunction with other techniques like proof by contradiction or proof by contrapositive, that's perfectly fine.)

Good luck, and have fun!

Starter Files

Here are the starter files for the problems you'll submit electronically:

Unpack the files somewhere convenient and open up the bundled project.

If you would like to type your solutions in $\LaTeX$, you may want to download this template file where you can place your answers:

Problem One: Induction Proof Critiques

Below are a collection of proofs by induction. For each proof, do the following:

- Critique the proofwriting style in regards to the Induction Proofwriting Checklist and Guide to Induction.

- Identify any logic errors in the execution of the proofs.

- Determine whether the "theorem" being proved is actually true. If it's true, just tell us that it's true. If it's false, give a counterexample.

You do not need to rewrite these proofs – just give us your feedback on the items we mentioned by filling in this table:

| Checklist Item | Violation? | If Yes, where is the error? |

|---|---|---|

| Make $P(n)$ a predicate, not a number or function.” | Yes/No | |

| Watch your variable scoping in $P(n)\text.$ | Yes/No | |

| "Build up" if $P(n)$ is existentially quantified; "build down" if $P(n)$ is universally-quantified. | Yes/No | |

| Choose the simplest base cases possible, and avoid redundant base cases. | Yes/No | |

| Are there any logic errors? If so, where? | ||

| Is the overall theorem true? | ||

-

Critique the following proof about sums of natural numbers.

Theorem: The sum of the first $n$ natural numbers is $\frac{n(n - 1)}{2}$.

Proof: Let $P(n) = \frac{n(n - 1)}{2}$. We will prove by induction on $n$ that $P(n)$ holds for all $n \in \naturals$, from which theorem follows.

As our base cases, we prove $P(0)$ and $P(1)$. First we’ll prove $P(0)$, that the sum of the first zero natural numbers is $\frac{0(0 - 1)}{2}$. The sum of no numbers is the empty sum $(0)\text,$ and we see that $\frac{0(0 - 1)}{2} = 0$, so $P(0)$ is true. Next, we’ll prove $P(1)$. The sum of the first natural number is $0$ (since $0$ is the smallest natural number), and we note that $\frac{1(1 - 1)}{2} = 0$, so $P(1)$ is true.

For our inductive step, assume for all natural numbers $k$ that $P(k)$ is true. This means

\[0 + 1 + 2 + \dots + (k - 1) \quad = \quad \frac{k(k - 1)}{2}\text.\]We will prove $P(k+1)$, that the sum of the first $k+1$ natural numbers is equal to $\frac{(k + 1)k}{2}$. Starting with the sum of the first $k+1$ natural numbers, we see that

\[\begin{array}{lcl} 0 + 1 + 2 + \dots + (k - 1) + k & = & \frac{(k+1)k}{2} \\ 0 + 1 + 2 + \dots + (k - 1) & = & \frac{(k + 1)k}{2} - k \\ 0 + 1 + 2 + \dots + (k - 1) & = & \frac{(k + 1)k}{2} - \frac{2k}{2}\\ 0 + 1 + 2 + \dots + (k - 1) & = & \frac{(k + 1 - 2)k}{2} \\ 0 + 1 + 2 + \dots + (k - 1) & = & \frac{k(k - 1)}{2} \text. \end{array}\]We've reached our inductive hypothesis, so the equation is true. Thus $P(k+1)$ holds, completing the induction. $\qed$

-

Critique the following proof about directed graphs.

Theorem: No directed graphs have any cycles.

Proof: Let $P(n)$ be the statement “for any $n \in \naturals$, no directed graph with $n$ nodes contains a cycle.” We will prove by induction that $P(n)$ holds for all $n \in \naturals$, from which the theorem follows.

As a base case, we prove $P(0)$, that no directed graphs with $0$ nodes contain a cycle. To see this, consider any directed graph $G$ with no nodes. Since $G$ has no nodes, it has no closed walks, since all closed walks contain at least one node. Therefore, $G$ has no cycles, as required.

For our inductive step, assume for some arbitrary $k \in \naturals$ that P(k) is true and no directed graph with $k$ nodes has any cycles. We will prove that $P(k+1)$ is true, namely, that no directed graphs with $k+1$ nodes have any cycles.

Consider a directed graph $G$ with $k$ nodes. By our inductive hypothesis, we know that $G$ has no cycles. Now, consider the graph $G'$ formed by adding a new node $v$ to $G$, then adding edges from $v$ to each node in $G$. We claim that this directed graph has no cycles. To see this, note that any cycle in $G'$ must involve $v$, since $G$ has no cycles on its own. But this is impossible, since any walk that leaves $v$ can never return to it and therefore can't be a closed walk. Therefore, $G'$ has no cycles, so $P(k+1)$ holds, completing the induction. $\qed$

Problem Two: Recurrence Relations

A recurrence relation is a way of defining an infinitely long sequence (usually, a sequence of numbers). A recurrence relation specifies the value of the first term or terms of the sequence, then defines the remaining entries from the previous terms. For example, here’s a simple recurrence relation:

\[a_0 = 1 \qquad a_{n+1} = 2a_n\]The first terms of this sequence are given as follows:

- $a_0 = 1$, since that’s what the first rule says.

- $a_1 = 2$, since the second rule says that $a_1 = 2a_0 = 2 \cdot 1 = 2\text.$

- $a_2 = 4$, since the second rule says that $a_2 = 2a_1 = 2 \cdot 2 = 4\text.$

- $a_3 = 8$, since the second rule says that $a_3 = 2a_2 = 2 \cdot 4 = 8\text.$

Extending further, this sequence starts off with the numbers

\[1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, \dots,\]which all happen to be powers of two. It turns out that this isn't a coincidence – this recurrence relation perfectly describes the powers of two.

Fill in the blanks below to complete the proof by induction.

Theorem: For all natural numbers $n$, we have $a_n = 2^n$.

Proof: Let $P(n)$ be the statement "$a_n = 2^n$." We will prove by induction that $P(n)$ holds for all $n \in \naturals$, from which the theorem follows.

As our base case, we prove $P(\blank)$, that $\blank$. To see this, $\blank$.

For our inductive step, assume for some arbitrary $k \in \naturals$ that $P(k)$ is true, meaning that $\blank$. We need to show $P(\blank)$, meaning that $\blank$. To see this, note that

\[\begin{aligned} a_{k+1} &= \blank \\ &= \blank && \text{(by our IH)} \\ &= \blank \text. \end{aligned}\]Therefore, we see that $\blank$, so $P(\blank)$ is true, completing the induction. $\qed$

The relative sizes of the blanks here do not necessarily indicate how much you need to write in each spot.

In case you’re wondering what you’re asked to prove here, you can think of this recurrence relation as a mathematical way of writing out this recursive function:

int a(int n) {

if (n == 0) return 1;

return 2 * a(n - 1);

}

For any $n \in \naturals$, you can compute a(n) by just running this code, and after doing some computation it will return the value of $a_n$. What we’re asking you to do is the mathematical equivalent of showing that the value returned by a(n) is always $2^n$. While it might help to think about things in terms of this analogy, your proof should not reference this code and should just use the definitions given in the problem statement.

Taking a recurrence relation like the relation $a_n$ here and finding a simple, non-recursive expression for it is called solving the recurrence. It's common in theoretical CS to need to solve recurrences. For example, when determining the efficiency of a recursive algorithm, you might first start by writing a recurrence relation for its runtime, then solve the recurrence to get a simpler, direct way of calculating its efficiency. Take CS161 to learn how to do this!

Problem Three: Stacking Cans

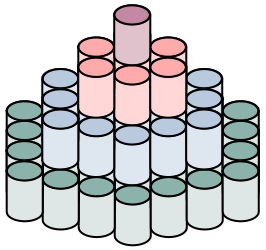

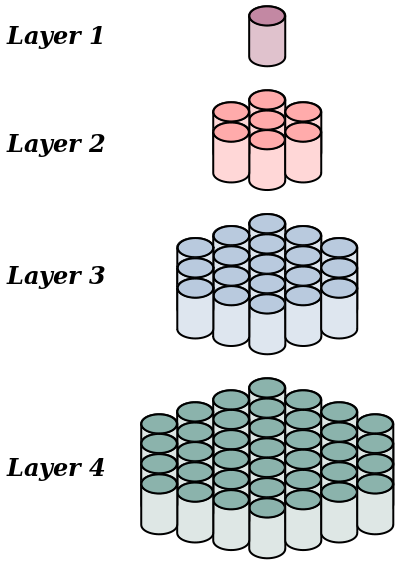

On a recent trip to grocery store, I saw a bunch of cans stacked up in a pyramid like the one shown here. Each layer in the pyramid was made from a hexagon of cans, with each hexagon slightly bigger than the hexagon below it.

I went home to try making something like this from the cans in my pantry and quickly figured out that I didn't have enough cans to do so. Turns out, you need a lot of cans to make a pyramid like this! In this question, you'll figure out just how many cans are required.

The first step in this process is to figure out how many cans are in each hexagon. Here are cross-sectional views of the hexagons from the pyramid:

Notice that in moving from the first hexagon to the second we've surrounded the center can in six cans. In moving from the second hexagon to the third we've surrounded the seven previous cans with twelve new cans. And in moving from the third hexagon to the fourth we've surrounded the previous nineteen cans with eighteen new cans. And more generally, it seems like we go from one hexagon to the next by surrounding the previous hexagon with a number of cans equal to the next multiple of six. That lets us write a recurrence relation for how many cans are in the $n$th hexagon:

\[h_1 = 1 \qquad h_{n+1} = h_n + 6n \text.\]Pause for a minute to make sure you see why this is.

-

Prove by induction that $h_n = 3n(n - 1) + 1$ for all natural numbers $n \ge 1 \text.$

As in Problem Two, you begin here with the recursive definition of $h$ given above, then need to show that the terms of the series are also given by the simpler formula $3n(n - 1) + 1$.

Now that we know how many cans are in each hexagon, we can start working out how many cans it takes to make a pyramid with $n$ layers.

-

Fill in the following blanks. No justification is required.

- A 0-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 1-layer tower has $1$ can in it.

- A 2-layer tower has $8$ cans in it.

- A 3-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 4-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 5-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 6-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 7-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 8-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 9-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

- A 10-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

Just to make sure you didn't miss it, we want the total number of cans in the full tower made of $n$ layers, not just the number of cans in layer $n\text.$

-

Fill in the following blank with a simple mathematical expression (e.g. $n^2 + 19n + 1$, $\sqrt{n^2 + 5}$, $\floor{\frac{n}{2}}^2$, etc, but not a recurrence relation like $t_{n+1} = t_n + h_{n+1}$). No justification is required.

An $n$-layer tower has $\blank$ cans in it.

-

Prove by induction on $n$ that your formula from part (iii) holds for all natural numbers $n$.

We've asked you to prove this is true for all natural numbers $n$, including when $n = 0\text.$

Your answer to part (iv) explains why I wasn't able to build any reasonable pyramid from the cans I have at home. It's worth taking a minute or two to ponder how much it would cost to build a pyramid twenty layers deep!

A purely optional but very rewarding question to ponder: the formula you proved correct in part (iv) suggests there's a completely different way to arrange the cans in the pyramid into an appealing geometrical shape. What is that other shape? Can you find a way to explain why that shape - which superficially has nothing to do with hexagons - relates back to hexagonal layers?

Problem Four: Diplomacy

There is a summit with diplomats from around the world. Unfortunately, these are angry diplomats, and each diplomat hates zero, one, or two other diplomats at the event. Hatred is not necessarily reciprocal - diplomat $A$ may hate diplomat $B$ even if diplomat $B$ doesn't hate diplomat $A\text.$ No diplomat hates themselves.

To keep things civil, the event organizer sets the following rule: no diplomat is allowed to stay at the same hotel as a diplomat they hate. The question then arises - how many hotels are necessary to house the diplomats?

-

Give a group of five diplomats where it's necessary for each diplomat to stay in a different hotel. No justification is necessary. (This shows that there are situations in which five hotels are required to house everyone.) We encourage you to give your answer as a directed graph where each node is a diplomat and each edge $(u, v)$ represents diplomat $u$ hating diplomat $v\text.$

Amazingly, while you might sometimes need five hotels, you never will need more than that many. More specifically, given any group of diplomats, each of whom hates at most two others, there is always a way to assign them to five hotels without placing any diplomat in the same hotel as someone they hate.

We’re going to ask you to prove this using a proof by induction with this predicate $P(n)$:

$P(n)$ is the predicate “for any group of $n$ diplomats, each of whom hate at most two other diplomats, there is a way to house the diplomats in five hotels so that no diplomat stays at a hotel with another diplomat they hate”

Before proceeding, let’s confirm you see the general structure of the proof.

-

Is $P(n)$ a universally-quantified statement or an existentially-quantified statement? Based on that, will you “induct up,” or will you “induct down?”

There are multiple quantifiers in $P(n)$. We care about the first one.

-

Prove by induction that $P(n)$ is true for all $n \in \naturals$.

What can you say about the least-hated diplomat in the group? Use the pigeonhole principle.

Problem Five: Regular Graphs

A graph $G = (V, E)$ is called $d$-regular if every node in $G$ has degree exactly $d$. (As a reminder, the degree of a node $v$ is the number of edges that have $v$ as an endpoint, or, equivalently, the number of nodes that $v$ is adjacent to.)

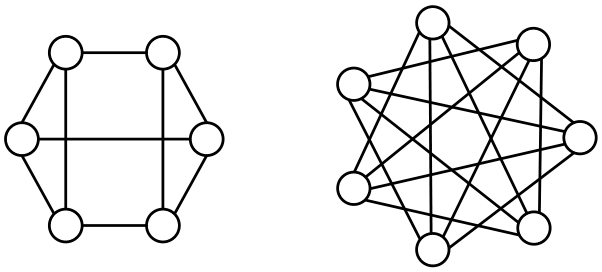

For example, here's a 3-regular graph with 6 nodes and a 4-regular graph with 7 nodes:

Prove by induction that for all natural numbers $n$ there exists an $n$-regular graph containing exactly $2^n$ nodes.

Is this a problem where you'll "induct up," or a problem where you'll "induct down?"

As a hint, moving from $2^k$ to $2^{k+1}$ doubles the number of nodes in the graph, and moving from $2^{k+1}$ to $2^k$ halves the number of nodes in the graph. If you think this is an "induct up" problem, try finding a natural way to "double" a graph. If you think this is an "induct down" problem, try finding a natural way to "halve" a graph.

Regular graphs often make appearances in combinatorics and theoretical computer science. Graphs with the specific property you're exploring in this problem - where there are a huge number of nodes of modest degree - have applications in parallel computing, network design, and error-correcting codes. Take CS144 (Computer Networks), CS149 (Parallel Computing) or CS250 (Algebraic Error-Correcting Codes) to learn more!

Problem Six: Recursive Functions

It's common to see mathematical functions defined recursively. For example, consider the function $f : \naturals \to \naturals$ defined as follows:

\[f(n) = \begin{cases} n &\text{ if } n \le 1 \\ 1 + f(n - 2) &\text{ otherwise } \end{cases}\]So, for example, we have $f(0) = 0$ because the first case applies, and similarly $f(1) = 1\text.$ To see what $f(2)$ is, we see that the rules defining $f$ say that $f(2) = 1 + f(2 - 2) = 1 + f(0)\text,$ and since we know $f(0) = 0$ this means that $f(2) = 1\text.$ We also can see that $f(3) = 1 + f(1) = 1 + 1 = 2\text.$

-

Fill in the following blanks. No justification is required.

- $f(4) = \blank\text.$

- $f(5) = \blank\text.$

- $f(6) = \blank\text.$

- $f(7) = \blank\text.$

- $f(8) = \blank\text.$

Some recursive functions are more elaborate than others. For example, consider this function $g : \naturals \to \naturals\text,$ which is similarly defined recursively:

\[g(n) = \begin{cases} 0 &\text{ if } n = 0 \\ g(k) &\text{ if } n \ge 1 \land \exists k \in \naturals. n = 2k \\ 1 + g(k) &\text{ if } n \ge 1 \land \exists k \in \naturals. (n = 2k + 1) \\ \end{cases}\]As with all piecewise functions, evaluating $g$ is largely an exercise in slowly and methodically working by cases.

-

Fill in the following blanks. No justification is required.

- $g(0) = \blank\text.$

- $g(1) = \blank\text.$

- $g(2) = \blank\text.$

- $g(3) = \blank\text.$

- $g(4) = \blank\text.$

- $g(5) = \blank\text.$

- $g(6) = \blank\text.$

- $g(7) = \blank\text.$

Here's one last function. If you take CS161, you'll see a function very similar to this one play an important role in one of the lectures. We define $h : \naturals \to \naturals$ as follows:

\[h(n) = \begin{cases} 0 &\text{ if } n = 0 \\ n + h(\floor{\frac{7n}{10}}) + h(\floor{\frac{n}{5}}) &\text{ otherwise } \end{cases}\]This one is a bit trickier to evaluate by hand than the others, so let's get the computer to do it for us.

-

In the starter files for this assignment, implement the function

int compute_h(int n);in the file

RecursiveFunctions.cppso that it computes and returns the value of $h(n)\text.$ You do not need to worry about the case where the input value $n$ is negative.

It's not immediately clear what this function looks like, but it turns out to be pretty nicely-behaved. If you use the provided starter files, you can see a plot that compares $h(n)$ against the function $10n$ over a range of values. The value of $h(n)$ grows larger and larger as $n$ increases, but never overshoots $10n\text.$ That's not a coincidence.

-

Prove by induction that $h(n) \le 10n$ for all $n \in \naturals\text.$ You may want to make use of the following facts:

-

For all real numbers $x\text,$ we have $\floor{x} \le x \le \ceil{x}\text.$

-

If $x$ and $y$ are integers, then $x \lt y$ if and only if $x \le y - 1\text.$

-

The function $h(n)$ from parts (iii) and (iv) of this problem arises in the context of the median-of-medians algorithm, a very clever algorithm for finding the $k\text{th}$ largest element of a set of data. To learn more, take CS161!

Problem Seven: Hereditary Sets

A hereditary set is a special type of set that is defined as follows:

\[\forall S. (Hereditary(S) \quad \leftrightarrow \quad Set(S) \land \forall T \in S. Hereditary(T))\]This is a recursive definition that defines hereditary sets in terms of themselves. Accordingly, it's not surprising to see induction make an appearance when reasoning about them.

Prove by induction that $\wp^n(\emptyset)$ is a hereditary set for every natural number $n\text.$

Here, $\wp^n$ represents the iterated application of powersets along the lines of how $f^n$ represents iterating a function $f$ $n$ total times. So, for example, $\wp^3(\emptyset) = \powerset{\powerset{\powerset{\emptyset}}}$ and $\wp^0(\emptyset) = \emptyset\text.$

Proceed slowly here and work out what you're assuming and what you need to prove. This is a proof on sets, so we're looking for the same level of detail and rigor here as you saw on PS3.

Two fun facts about what you just proved. First, the sets you just reasoned about are enormously huge. Specifically, it's possible to show that

\[\abs{\wp^n(\emptyset)} = 2^{2^{2^{2^{\dots^2}}}}\text,\]where there are $n$ copies of $2$ in the tower. This operation of "raise $2$ to itself $n$ times" is called tetration, where tetration is to exponentation what exponentiation is to multiplication and what multiplication is to addition. These numbers grow incredibly quickly; in fact, $\abs{\wp^7(\emptyset)}$ is inconcievably huge: its number of digits is so big, we couldn't write it out using all the protons in the known universe! Yet surprisingly tetration sometimes appears in the analysis of algorithms and data structures - take CS166 for details.

Second, hereditary sets have applications in foundational mathematics, a field that studies how to build all of mathematics from first principles. In a sense, hereditary sets represent the sets you can make if you only allow sets to contain other sets. You sometimes hear the class of all sets that can be made this way referred to as the von Neumann universe. To learn more, take Math 161 (Set Theory). Don't let the course number scare you; just because $161 \gt 3 \cdot 51$ doesn't mean it's three times harder than Math 51. In fact, Math 161 is an excellent follow-up course to CS103!

Optional Fun Problem: Egyptian Fractions

Leonardo Fibonacci, an eleventh-century Italian mathematician, is credited with introducing Hindu-Arabic numerals (the number system we use today) to Europe in his book Liber Abaci. The book Liber Abaci is also the source of the Fibonacci sequence (a sequence that begins 0, 1 and where each successive term is the sum of the two previous terms).

Relevant for this problem, Liber Abaci also described a method of writing out fractions called Egyptian fractions, which has been employed since ancient times; the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, composed about 3,500 years ago in Thebes, includes several tables of fractions written out this way.

An Egyptian fraction is a sum of distinct fractions whose numerators are all 1 (these fractions are called unit fractions). For example, here are some sample Egyptian fraction representations:

\[\begin{array}{c} \frac{2}{3} = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{6} \\ \frac{2}{15} = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{30} \\ \frac{7}{15} = \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{120} \\ \frac{2}{85} = \frac{1}{51} + \frac{1}{255} \end{array}\]Egyptian fractions are useful for divvying up objects fairly. For example, suppose you have two cakes to distribute to fifteen people – that is, everyone should get a $\frac{2}{15}$ fraction of those cakes. Begin by slicing each cake into tenths and giving each person one ($\frac{1}{10}$). Now, take the remaining tenths you haven’t distributed and cut them into thirds, giving thirtieths of the original cake. Each person then takes one of those ($\frac{1}{30}$). Because $\frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{30} = \frac{2}{15}$, everyone gets their fair share. Pretty cool, isn’t it?

It's not immediately obvious that every fraction between 0 and 1 can be written this way, but, surprisingly, that is indeed the case. One way of finding an Egyptian fraction representation of a number is to use a greedy algorithm that works by finding the largest unit fraction at any point that can be subtracted out from the rational number. For example, to compute an Egyptian fraction representation for $\frac{42}{137}$, we would start off by noting that $\frac{1}{4}$ is the largest unit fraction less than $\frac{42}{137}$. We then say that

\[\frac{42}{137} = \frac{1}{4} + (\frac{42}{137} - \frac{1}{4}) = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{31}{548} \text.\]We then repeat this process by finding the largest unit fraction less than $\frac{31}{548}$ and subtracting it out. This number is $\frac{1}{18}$, so we get

\[\frac{42}{137} = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{18} + (\frac{31}{548} - \frac{1}{18}) = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{18} + \frac{5}{4,932} \text.\]The largest unit fraction we can subtract from $\frac{5}{4932}$ is $\frac{1}{987}$:

\[\frac{42}{137} = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{18} + \frac{1}{987} (\frac{5}{4,932} - \frac{1}{987}) = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{18} + \frac{1}{987} + \frac{1}{1,622,628} \text.\]And at this point we're done, because the leftover fraction is itself a unit fraction.

Prove that the greedy algorithm for Egyptian fractions always terminates for any rational number $r$ in the range $0 \lt r \lt 1$ and always produces a valid Egyptian fraction. (A rational number is a real number that can be written as $r = \frac{p}{q}$ for some integers $p$ and $q$ where $q \ne 0$.) That is, the sum of the unit fractions should be the original number, there should only be finitely many fractions, and no unit fraction should be repeated. This shows that every rational number in the range $0 \lt r \lt 1$ has at least one Egyptian fraction representation.